GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion organization was organized by the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, largely on the initiative of the English Quaker Joseph Sturge. The exclusion of women from the convention gave a great impetus to the women’s suffrage movement in the United States.Today in our History – The World Anti-Slavery Convention met for the first time at Exeter Hall in London, on 12–23 June 1840.The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade (officially Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade) was principally a Quaker society founded in 1787 by 12 men, nine of whom were Quakers and three Anglicans, one of whom was Thomas Clarkson.Thanks to their efforts, the international slave trade was abolished throughout the British Empire with the passing of the Slave Trade Act 1807. The Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery Throughout the British Dominions, in existence from 1823 to 1838, helped to bring about the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, advocated by William Wilberforce, which abolished slavery in the British Empire from August 1834, when some 800,000 people in the British empire became free.Similarly, in the 1830s many women and men in America acted on their religious convictions and moral outrage to become a part of the abolitionist movement. Many women in particular responded to William Lloyd Garrison’s invitation to become involved in the American Anti-Slavery Society. They were heavily involved, attending meetings and writing petitions. Arthur Tappan and other conservative members of the society objected to women engaging in politics publicly.Given the perceived need for a society to campaign for anti-slavery worldwide, the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (BFASS) was accordingly founded in 1839. One of its first significant deeds was to organise the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840: “Our expectations, we confess, were high, and the reality did not disappoint them.” The preparations for this event had begun in 1839, when the Society circulated an advertisement inviting delegates to participate in the convention. Over 200 of the official delegates were British. The next largest group was the Americans, with around 50 delegates. Only small numbers of delegates from other nations attended.Benjamin Robert Haydon painted The Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840, a year after the event that today is in the National Portrait Gallery. This very large and detailed work shows Alexander as Treasurer of the new Society. The painting portrays the 1840 meeting and was completed the next year. The new society’s mission was “The universal extinction of slavery and the slave trade and the protection of the rights and interests of the enfranchised population in the British possessions and of all persons captured as slaves.” The circular message, distributed in 1839, provoked a controversial response from some American opponents of slavery. The Garrisonian faction supported the participation of women in the anti-slavery movement. They were opposed by the supporters of Arthur and Lewis Tappan. When the latter group sent a message to the BFASS opposing the inclusion of women, a second circular was issued in February 1840 which explicitly stated that the meeting was limited to “gentlemen”.Despite the statement that women would not be admitted, many American and British female abolitionists, including Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lady Byron, appeared at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. The American Anti-Slavery Society, the Garrisonian faction, made a point to include a woman, Lucretia Mott, and an African American, Charles Lenox Remond, in their delegation. Both the Massachusetts and Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Societies sent women members as their delegates. Cady Stanton was not herself a delegate; she was in England on her honeymoon, accompanying her husband Henry Stanton, who was a delegate. (Notably, he was aligned with the American faction that opposed women’s equality.) Wendell Phillips proposed that female delegates should be admitted, and much of the first day of the convention was devoted to discussing whether they should be allowed to participate. Published reports from the convention noted “The upper end and one side of the room were appropriated to ladies, of whom a considerable number were present, including several female abolitionists from the United States.” The women were allowed to watch and listen from the spectators’ gallery but could not take part.In sympathy with the excluded women, the Americans William Garrison, Charles Lenox Remond, Nathaniel P. Rogers, and William Adams refused to take their seat as delegates as well, and joined the women in the spectator’s gallery.Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who eight years later organized the Seneca Falls Convention, met at this convention.The convention’s organising committee had asked the Reverend Benjamin Godwin to prepare a paper on the ethics of slavery. The convention unanimously accepted his paper, which condemned not just slavery but also the world’s religious leaders and every community who had failed to condemn the practise. The convention resolved to write to every religious leader to share this view. The convention called on every religious communities to eject any supporters of slavery from their midst.George William Alexander reported on his visits in 1839, with James Whitehorn, to Sweden and the Netherlands to discuss the conditions of slaves in the Dutch colonies and in Suriname. In Suriname, he reported, there were over 100,000 slaves with an annual attrition rate of twenty per cent. The convention prepared open letters of protest to the respective sovereigns.Joseph Pease spoke and accused the British government of being complicit in the continuing existence of slavery in India.After leaving the convention on the first day, being denied full access to the proceedings, Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton “walked home arm in arm, commenting on the incidents of the day, [and] we resolved to hold a convention as soon as we returned home, and form a society to advocate the rights of women.” Eight years later they hosted the Seneca Falls Convention in Seneca Falls, New York.One hundred years later, the Women’s Centennial Congress was held in America to celebrate the progress that women had made since they were prevented from speaking at this conference. Research more about this great American Champion event and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

Month: June 2021

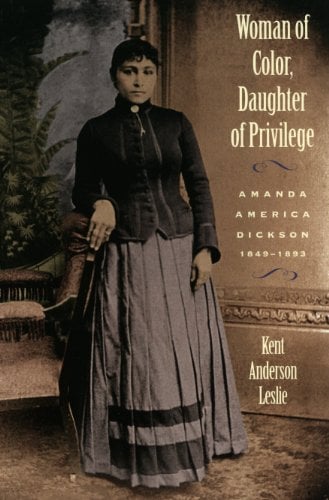

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a Bi-racial socialite in Georgia who became known as one of the wealthiest African American women of the 19th century after inheriting a large estate from her white planter father.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a Bi-racial socialite in Georgia who became known as one of the wealthiest African American women of the 19th century after inheriting a large estate from her white planter father.Born into slavery, she was the child of David Dickson, a white planter, and Julia Frances Lewis Dickson, one of his slaves, who was thirteen when her daughter was born. She was raised by Elizabeth Sholars Dickson, her white grandmother and mistress. She was educated and schooled in the social skills of her father’s class, and he helped her to enjoy a life of privilege away from the harsh realities of slavery before emancipation following the Civil War. In her late 20s, she also attended the normal school of Atlanta University, from 1876 to 1878. After her father’s death in 1885 and a successful ruling in a challenge to his will by his white relatives, she inherited his estate, which included 17,000 acres of land in Hancock and Washington counties in Georgia. She married twice: her first husband was white and their sons were mixed-race. Their wealth enabled them to marry well.Today in our History – June 11, 1893 – Amanda America Dickson (November 20, 1849 – June 11, 1893) died.Amanda America Dickson was born into slavery in Hancock County, Georgia. Her enslaved mother, Julia Frances Lewis Dickson, was just 13 when she was born. Her father, David Dickson, was a white planter who owned her mother; he was one of the eight wealthiest planters in the county. When he was 40 years old, David Dickson had raped 12-year-old Julia Dickson, and she became pregnant. After Amanda was weaned, she was taken from her enslaved mother and maternal grandmother, Rose Dickson, to be raised in the household of her white grandmother and owner, Elizabeth Sholars Dickson. As Amanda grew, her grandmother used her as a domestic servant.Throughout Amanda’s childhood, her father became wealthier and more famous, renowned for his innovative and successful farming techniques. David Dickson showed that farmers could profit from slave labor without having to resort to violence to keep them in submission. By 1861, he was known as the “Prince of Georgia Farmers,” having contributed perhaps more than any other farmer in Georgia at that time to the prosperity of the region.Amanda’s father showered her with love and affection. Her mother was a household slave, assigned as David’s housekeeper, and she was forced also to provide him with sex. Amanda benefited greatly from her father’s social status, enabling her to live a life of relative privilege as a slave child.Evidence suggests that David Dickson took charge of Amanda’s education. In her white grandmother’s household, she learned to read, write, and play the piano, unlike what was permitted for her enslaved relatives. Amanda also learned rules of social etiquette appropriate for the social standing of her father’s side of the family. She learned to dress in a modest, elegant fashion and how to present herself as a “lady”. Amanda also learned from her father how to conduct business transactions responsibly and how to maintain and protect her finances after marriage.In 1864, Amanda’s grandmother Elizabeth Sholars Dickson died. Amanda and her grandmother Elizabeth had shared a particularly close relationship, with Amanda spending much time in her grandmother’s room. Amanda was held as Elizabeth’s slave until her death. Beginning in 1801, Georgia had prohibited slaveholders from independently freeing their slaves. Therefore, Elizabeth and David Dickson had no means to manumit Amanda and keep her with them in Georgia until the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, was ratified on December 6, 1865. At the age of twenty-seven, Amanda chose to leave the security of her home at her father’s plantation in Hancock County, Georgia to attend the normal school of Atlanta University, where she studied teaching from 1876 to 1878.Amanda America Dickson spent the last eleven months of her life as the wife of Nathan Toomer, from Perry, Georgia whom she married on July 14, 1892. Her health was fragile throughout her second marriage, as she had several health problems which required the continual attention of her family physician, Thomas D. Coleman.By 1893, Amanda America’s health had greatly improved, but a disturbing family ordeal would be the catalyst for the further deterioration of her health and eventual death. Her younger son, twenty-three-year-old Charles Dickson, who was married to Kate Holsey, became infatuated with Mamie Toomer, one of his stepsisters who was only fourteen years old. On March 10, 1893, Nathan and Amanda brought Mamie to the St. Francis School and Convent in Baltimore, Maryland, an order of black nuns, in an attempt to protect her from Charles Dickson’s misguided affection. Charles Dickson conspired with his brother-in-law Dunbar Walton, his sister-in-law Carrie Walton Wilson, and a hired man, Louis E. Frank, to kidnap Mamie Toomer. Their plan was foiled, and ultimately, Dunbar Walton, Louis E. Frank, and their lawyer, E. J. Waring, were indicted by the grand jury of Baltimore, Maryland for conspiracy to kidnap Mamie Toomer. Charles Dickson escaped without any legal ramifications for his actions.In June 1893, with the kidnapping drama (involving Mamie Toomer, Charles Dickson, and Charles Dickson’s co-conspirators) behind them, Nathan and Amanda America purchased two first-class tickets from a sales representative of the Pullman Palace Car Company to transport them from Baltimore, Maryland back home to Augusta, Georgia. Because of racial discrimination, they were denied their first-class accommodations and direct, unimpeded travel to Augusta, Georgia. The delayed travel to Augusta and the conditions in the Pullman car, most notably the rising temperature, became intolerable for Amanda America. As a result, her health quickly deteriorated. Dr. F. D. Kendall, who examined her on the morning of June 9, 1893, noted that her heart and lungs appeared to be fine, but that she was obviously very nervous and anxious to return home. Dr. Kendall gave her anodyne, a pain-relieving medication.Nathan and a very ill Amanda America arrived back at their home in Augusta, Georgia between four and five in the afternoon on June 9, 1893. She was quickly tended to by Dr. Eugene Foster, in place of their family physician, Thomas D. Coleman, who was out of town. She was diagnosed with neurasthenia (general exhaustion of the nervous system) or Beard’s disease. Symptoms of neurasthenia, as described by nineteenth-century physicians, include “sick headache, noises in the ear, atonic voice, deficient mental control, bad dreams, insomnia, nervous dyspepsia (disturbed digestion), heaviness of the loin and limb, flushing and fidgetiness, palpitations, vague pains and flying neuralgia (pain along a nerve), spinal irritation, uterine irritability, impotence, hopelessness, claustrophobia, and dread of contamination.” Amanda America Dickson Toomer died on June 11, 1893, with “complications of diseases” being the cause of death listed on her death certificate.Amanda America Dickson Toomer’s funeral took place at the Trinity Colored Methodist Episcopal Church in Augusta, Georgia. Amanda America died without a will, which resulted in a legal battle after her death for control of her estate. Her mother, Julia Frances Lewis Dickson, and her second husband, Nathan Toomer, both petitioned in court to be designated the temporary administrator of her estate. Ultimately, Julia Dickson, Nathan Toomer, and Amanda America’s younger son, Charles Dickson, were able to settle the dispute over Amanda America’s estate amicably out of court.Nine months after her death, Nathan Toomer married Nina Pinchback, the daughter of P. B. S. Pinchback, the Reconstruction Era senator-elect from Louisiana. On December 26, 1894, they became parents to Jean Toomer, a Harlem Renaissance writer who wrote the novel Cane (1923). A House Divided (2000) is the television movie that depicts the life of Amanda America Dickson. It stars Jennifer Beals as Amanda America Dickson, Sam Waterston as David Dickson, LisaGay Hamilton as Julia Frances Lewis Dickson, and Shirley Douglas as Elizabeth Sholars Dickson. Research more about this great American Champion story and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

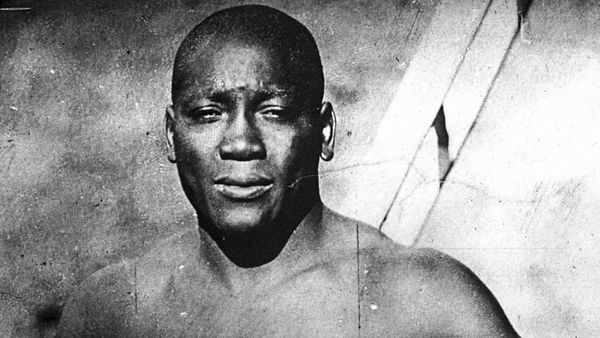

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American boxer who, at the height of the Jim Crow era, became the first African American world heavyweight boxing champion (1908–1915).

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American boxer who, at the height of the Jim Crow era, became the first African American world heavyweight boxing champion (1908–1915). Widely regarded as one of the most influential boxers of all time, one of the period’s most dominant champions, and as a boxing legend, his 1910 fight against James J. Jeffries was dubbed the “fight of the century”. According to filmmaker Ken Burns, “for more than thirteen years, he was the most famous and the most notorious African-American on Earth”. Transcending boxing, he became part of the culture and history of racism in the United States. In 1912, he opened a successful and luxurious “black and tan” (desegregated) restaurant and nightclub, which in part was run by his wife, a white woman. Major newspapers of the time soon claimed that he was attacked by the government only after he became famous as a black man married to a white woman, and was linked to other white women. He was arrested on charges of violating the Mann Act—forbidding one to transport a woman across state lines for “immoral purposes”—a racially motivated charge that embroiled him in controversy for his relationships, including marriages, with white women. Sentenced to a year in prison, he fled the country and fought boxing matches abroad for seven years until 1920 when he served his sentence at the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth.He continued taking paying fights for many years, and operated several other businesses, including lucrative endorsement deals. He died in a car crash on June 10, 1946, at the age of 68. He is buried at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago. On May 24, 2018, he was formally pardoned by U.S. President Donald Trump.Today in our History – June 10, 1946 – Jack Johnson dies.Johnson fought professionally from 1897 to 1928 and engaged in exhibition matches as late as 1945. He won the title by knocking out champion Tommy Burns in Sydney on December 26, 1908, and lost it on a knockout by Jess Willard in 26 rounds in Havana on April 5, 1915. Until his fight with Burns, racial discrimination had limited Johnson’s opportunities and purses. When he became champion, a hue and cry for a “Great White Hope” produced numerous opponents.At the height of his career, the outspoken Johnson was excoriated by the press for his flashy lifestyle and for having twice married white women. He further offended white supremacists in 1910 by knocking out former champion James J. Jeffries, who had been induced to come out of retirement as a “Great White Hope.” The Johnson-Jeffries bout, which was billed as the “Fight of the Century,” led to nationwide celebrations by African Americans that were occasionally met by violence from whites, resulting in more than 20 deaths across the country.In 1913 Johnson was convicted of violating the Mann Act by transporting a white woman—Lucille Cameron, his wife-to-be—across state lines for “immoral purposes.” He was sentenced to a year in prison and was released on bond, pending appeal. Disguised as a member of a black baseball team, he fled to Canada; he then made his way to Europe and was a fugitive for seven years.He defended the championship three times in Paris before agreeing to fight Willard in Cuba. Some observers thought that Johnson, mistakenly believing that the charge against him would be dropped if he yielded the championship to a white man, deliberately lost to Willard. From 1897 to 1928 Johnson had 114 bouts, winning 80, 45 by knockouts.In 1920 Johnson surrendered to U.S. marshals; he then served his sentence, fighting in several bouts within the federal prison at Leavenworth, Kansas. After his release he fought occasionally and performed in vaudeville and carnival acts, appearing finally with a trained flea act. He wrote two books of memoirs, Mes Combats (in French, 1914) and Jack Johnson in the Ring and Out (1927; reprinted 1975). He died in an automobile accident.In the years after Johnson’s death, his reputation was gradually rehabilitated. His criminal record came to be regarded as more a product of racially motivated acts than a reflection of actual wrongdoing, and members of the U.S. Congress—as well as others, notably actor Sylvester Stallone—attempted to secure for Johnson a posthumous presidential pardon, which is exceedingly rare. After hearing about Johnson from Stallone, Pres. Donald Trump officially pardoned the boxer in 2018.Johnson’s life story was lightly fictionalized in the hit play The Great White Hope (1967; filmed 1970), and he was the subject of Ken Burns’s documentary film Unforgivable Blackness (2004). Johnson was a member of the inaugural class of inductees into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

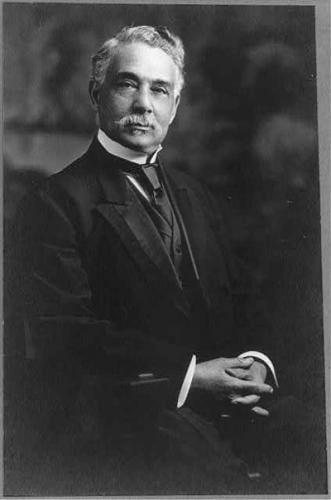

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American businessman, lawyer, politician, and civil rights leader from Nashville, Tennessee, who served as Register of the Treasury from 1911 to 1913.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American businessman, lawyer, politician, and civil rights leader from Nashville, Tennessee, who served as Register of the Treasury from 1911 to 1913.He is one of only five African Americans to have their signatures on American currency. He was one of four African-American politicians appointed to high position under President William Howard Taft, and they were known as his “Black Cabinet.” He was instrumental in founding civic institutions in Nashville to benefit the African-American business community and residents, including an emphasis on education.Today in our History – June 9, 1845 – James Carroll Napier (June 9, 1845 – April 21, 1940) was born.African American businessman and leader James C. Napier was born to free parents on June 9, 1845, in Nashville. His father, William Carroll, was a free hack driver and a sometime overseer. James attended the free blacks’ school on Line and High Street (now Sixth Avenue) with some sixty other black children until white vigilantes forced the school to close in 1856. He later attended school in Ohio after a December 1856 race riot ended black education in Nashville until the Union occupation in February 1862.Upon returning to the Union-held city of Nashville, Napier became involved in Republican Party politics. John Mercer Langston, an Ohio free black who became a powerful Republican politician and congressman, was a friend of Napier’s father. On December 30, 1864, Langston visited Nashville to speak to ten thousand black Union troops who had taken part in the recent and victorious battle of Nashville and to address the second Emancipation Day Celebration. He later invited Napier to attend the newly opened law school at Howard University in Washington, D.C., where he was a founding dean. After receiving his law degree in 1872, Napier returned to practice in Nashville. In 1873 he married Dean Langston’s youngest daughter, Nettie. This wedding was the biggest social event in nineteenth-century black Washington.Between 1872 and 1913 Napier became Nashville’s most powerful and influential African American citizen. Between 1878 and 1886 he served on the Nashville City Council and was the first black to preside over the council. He was instrumental in the hiring of black teachers for the “colored” public schools during the 1870s, the hiring of black “detectives,” and the organization of the black fire-engine company during the 1880s. His greatest political accomplishment was his service as President William H. Taft’s Register of the United States Treasury from 1911 to 1913.Napier also was a successful businessman and a personal friend of Booker T. Washington, whose wife Margaret was a personal friend of Nettie Langston Napier and often spent two or more weeks each summer at the Napier’s Nolensville Road summer home.Washington visited the city several times a year until his death in 1915. Napier was elected president of the National Negro Business League, which Washington had founded. The league held several of its annual meetings in Nashville, and Napier organized a local chapter of the league in 1905. He was a founder and cashier (manager) of the One Cent (now Citizens) Savings Bank organized in 1904, and he gave the new bank temporary quarters rent-free in his Napier Court office building at 411 North Cherry Street (now Fourth Avenue). He helped organize the 1905 Negro streetcar strike and the black Union Transportation Company’s streetcar lines. He presided over the powerful Nashville Negro Board of Trade and was on the boards of Fisk and Howard universities. Upon his death on April 21, 1940, Napier was interred in Greenwood Cemetery near members of his family and members of the Langston family. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American professional baseball pitcher who played in Negro league baseball and Major League Baseball (MLB).

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American professional baseball pitcher who played in Negro league baseball and Major League Baseball (MLB). His career spanned five decades and culminated with his induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.A right-handed pitcher, he first played for the semi-professional Mobile Tigers from 1924 to 1926. He began his professional baseball career in 1926 with the Chattanooga Black Lookouts of the Negro Southern League and became one of the most famous and successful players from the Negro leagues. On town tours across the United States, he would sometimes have his infielders sit down behind him and then routinely strike out the side.At age 42 in 1948, he made his major league debut for the Cleveland Indians. he was the first black pitcher to play in the American League and was the seventh black player to play in Major League Baseball. Also in 1948, he became the first player who had played in the Negro leagues to pitch in the World Series; the Indians won the Series that year. He played with the St. Louis Browns from 1951 to 1953, representing the team in the All-Star Game in 1952 and 1953. He played his last professional game on June 21, 1966, for the Peninsula Grays of the Carolina League. In 1971, he became the first electee of the Negro League Committee to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Today in our History – June 8, 1982 – Leroy Robert “Satchel” Paige (July 7, 1906 – June 8, 1982) dies.Leroy Robert Paige (better known as Satchel Paige) was an American baseball player who played for the Negro Leagues as well as MLB (Major League Baseball) teams. He was born on July 7, 1906 in Alabama, the 7th of 12 children in his family. His actual date of birth has been a point of contention but was officially determined from his birth certificate to be so. As a child, Paige used to work as a porter at the train station, earning a dime for carrying a bag. According to Paige, he used to tie a pole and rope around his shoulders to allow him to carry more luggage at once, due to which other kids would call him “satchel tree” thus earning him his nickname. According to another version of events, however, Paige got the nickname when he was caught trying to steal a bag.At the age of 13, Paige was caught trying to shoplift, which had been the third such incident to date. He was then sent to a state reform school, Industrial School for Negro Children in Mount Meigs, Alabama, where he stayed till the age of 18. During his 5 years there, his coach Edward Byrd taught him to pitch and polished his skills until he was released in December 1923. As African Americans were barred from the Major Leagues back then, Paige began his career with the Negro Southern League in 1926. He was drafted into the Chattanooga White Sox on a contract of $250 per month, where he had an impressive record. He was then traded to the Birmingham Black Barons of the major Negro National League (NNL). He played for several other leagues, both within the U.S. as well as in Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico and Mexico.Satchel Paige also played a lot of exhibition matches and barnstorming tours for extra money, sometimes against stars from the major leagues such as Joe DiMaggio and Dizzy Dean, who commented on his exceptional capabilities as a pitcher. Unfortunately, however, there are very few official statistics about his career, especially because he switched teams frequently and travelled quite often. According to some of Paige’s own statistics, as well as those compiled by others, he has pitched in more than 2,500 games, won more than 2,000 and played for over 250 teams which vouch for his exceptional career.In 1948, Paige was inducted into Major League Baseball. Jackie Robinson had been drafted by the Minor Leagues earlier but this was still a huge accomplishment, as Paige was 42 years old at the time and the first black player in the Major Leagues. He joined the Cleveland Indians, and his first season, helped them to win the World Series. He stayed with the team for one more season before moving to the St. Louis Browns, with whom he spent three seasons. His MLB record is just as impressive as his Negro League record, and Paige continued to play well into his fifties, becoming the oldest player in Major League history.Satchel Paige was a true baseball legend and his life has been documented in his autobiographies. He died of a heart attack at the age of 75 on June 8, 1982. He is widely claimed to be one of the best pitchers in the history of the game by numerous sports writers, critics and fans alike and several books, movies and documentaries have been made about his life and accomplishments. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

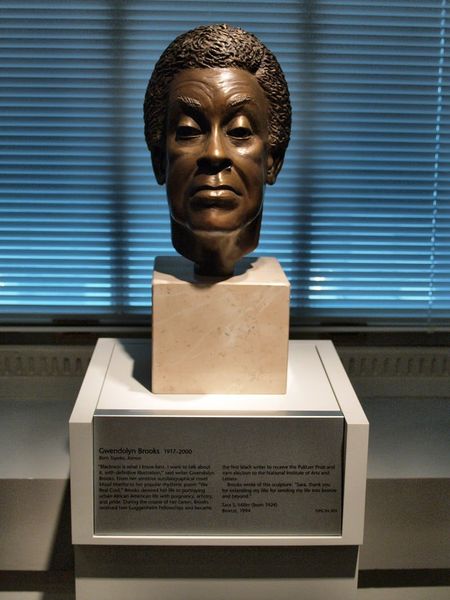

GM – FBF- Today’s American Champion was an American poet, author, and teacher.

GM – FBF- Today’s American Champion was an American poet, author, and teacher. Her work often dealt with the personal celebrations and struggles of ordinary people in her community. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry on May 1, 1950, for Annie Allen, making her the first African American to receive a Pulitzer Prize.Throughout her prolific writing career, she received many more honors. A lifelong resident of Chicago, she was appointed Poet Laureate of Illinois in 1968, a position she held until her death 32 years later. She was also named the Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress for the 1985–86 term. In 1976, she became the first African-American woman inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters.Today in our History – June 7, 1917 – Gwendolyn Brooks is born.Although she was born on 7 June 1917 in Topeka, Kansas–the first child of David and Keziah Brooks–Gwendolyn Brooks is “a Chicagoan.” The family moved to Chicago shortly after her birth, and despite her extensive travels and periods in some of the major universities of the country, she has remained associated with the city’s South Side.What her strong family unit lacked in material wealth was made bearable by the wealth of human capital that resulted from warm interpersonal relationships. When she writes about families that–despite their daily adversities–are not dysfunctional, Gwendolyn Brooks writes from an intimate knowledge reinforced by her own life.Brooks attended Hyde Park High School, the leading white high school in the city, but transferred to the all-black Wendell Phillips, then to the integrated Englewood High School. In 1936 she graduated from Wilson Junior College. These four schools gave her a perspective on racial dynamics in the city that continues to influence her work.Her profound interest in poetry informed much of her early life. “Eventide,” her first poem, was published in American Childhood Magazine in 1930. A few years later she met James Weldon Johnson and Langston Hughes, who urged her to read modern poetry–especially the work of Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, and e. c. cummings–and who emphasized the need to write as much and as frequently as she possibly could. By 1934 Brooks had become an adjunct member of the staff of the Chicago Defender and had published almost one hundred of her poems in a weekly poetry column.In 1938 she married Henry Blakely and moved to a kitchenette apartment on Chicago’s South Side. Between the birth of her first child, Henry, Jr., in 1940 and the birth of Nora in 1951, she became associated with the group of writers involved in Harriet Monroe’s still-extant Poetry: A Magazine of Verse. From this group she received further encouragement, and by 1943 she had won the Midwestern Writers Conference Poetry Award.In 1945 her first book of poetry, A Street in Bronzeville (published by Harper and Row), brought her instant critical acclaim. She was selected one of Mademoiselle magazine’s “Ten Young Women of the Year,” she won her first Guggenheim Fellowship, and she became a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Her second book of poems, Annie Allen (1949), won Poetry magazine’s Eunice Tietjens Prize. In 1950 Gwendolyn Brooks became the first African American to win a Pulitzer Prize. From that time to the present, she has seen the recipient of a number of awards, fellowships, and honorary degrees usually designated as Doctor of Humane Letters.President John Kennedy invited her to read at a Library of Congress poetry festival in 1962. In 1985 she was appointed poetry consultant to the Library of Congress. Just as receiving a Pulitzer Prize for poetry marked a milestone in her career, so also did her selection by the National Endowment for the Humanities as the 1994 Jefferson Lecturer, the highest award in the humanities given by the federal government.Her first teaching job was a poetry workshop at Columbia College (Chicago) in 1963. She went on to teach creative writing at a number of institutions including Northeastern Illinois University, Elmhurst College, Columbia University, Clay College of New York, and the University of Wisconsin.A turning point in her career came in 1967 when she attended the Fisk University Second Black Writers’ Conference and decided to become more involved in the Black Arts movement. She became one of the most visible articulators of “the black aesthetic.” Her “awakening” led to a shift away from a major publishing house to smaller black ones. While some critics found an angrier tone in her work, elements of protest had always been present in her writing and her awareness of social issues did not result in diatribes at the expense of her clear commitment to aesthetic principles. Consequently, becoming the leader of one phase of the Black Arts movement in Chicago did not drastically alter her poetry, but there were some subtle changes that become more noticeable when one examines her total canon to date.The ambiguity of her role as a black poet can be illustrated by her participation in two events in Chicago. In 1967 Brooks, who wrote the commemorative ode for the “Chicago Picasso,” attended the unveiling ceremony along with social and business dignitaries. The poem was well received even though such lines as “Art hurts. Art urges voyages . . .” made some uncomfortable. Less than two weeks later there was the dedication of the mural known as “The Wall of Respect” at 43rd and Langley streets, in the heart of the black neighborhood. The social and business elites of Chicago were not present, but for this event Gwendolyn Brooks wrote “The Wall.” In a measure these two poems illustrate the dichotomy of a divided city, but they also exemplify Brooks’s ability both to bridge those divisions and to utilize nonstrident protest.Gwendolyn Brooks has been a prolific writer. In addition to individual poems, essays, and reviews that have appeared in numerous publications, she has issued a number of books in rapid succession, including Maud Martha (1953), Bronzeville Boys and Girls (1956), and In the Mecca (1968). Her poetry moves from traditional forms including ballads, sonnets, variations of the Chaucerian and Spenserian stanzas as well as the rhythm of the blues to the most unrestricted free verse. In short, the popular forms of English poetry appear in her work; yet there is a strong sense of experimentation as she juxtaposes lyric, narrative, and dramatic poetic forms. In her lyrics there is an affirmation of life that rises above the stench of urban kitchenette buildings. In her narrative poetry the stories are simple but usually transcend the restrictions of place; in her dramatic poetry, the characters are often memorable not because of any heroism on their part but merely because they are trying to survive from day to day.Brooks’s poetry is marked by some unforgettable characters who are drawn from the underclass of the nation’s black neighborhoods. Like many urban writers, Brooks has recorded the impact of city life. But unlike the most committed naturalists, she does not hold the city completely responsible for what happens to people. The city is simply an existing force with which people must cope.While they are generally insignificant in the great urban universe, her characters gain importance–at least to themselves–in their tiny worlds, whether it be Annie Allen trying on a hat in a milliner’s shop or DeWitt Williams “on his way to Lincoln Cemetery” or Satin-Legs Smith trying to decide what outlandish outfit to wear on Sundays. Just as there is not a strong naturalistic sense of victimization, neither are there great plans for an unpromised future nor is there some great divine spirit that will rescue them. Brooks is content to describe a moment in the lives of very ordinary people whose only goal is to exist from day to day and perhaps have a nice funeral when they die. Sometimes these ordinary people seem to have a control that is out of keeping with their own insignificance.Although her poetic voice is objective, there is a strong sense that she–as an observer–is never far from her action. On one level, of course, Brooks is a protest poet; yet her protest evolves through suggestion rather than through a bludgeon. She sets forth the facts without embellishment or interpretation, but the simplicity of the facts makes it impossible for readers to come away unconvinced–despite whatever discomfort they may feel–whether she is writing about suburban ladies who go into the ghetto to give occasional aid or a black mother who has had an abortion.Trying to determine clear lines of influence from the work of earlier writers to later ones is always a risky business; however, knowing some identifiable poetic traditions can aid in understanding the work of Gwendolyn Brooks. On one level there is the English metaphysical tradition perhaps best exemplified by John Donne. From nineteenth-century American poetry one can detect elements of Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, and Paul Laurence Dunbar. From twentieth-century American poetry there are many strains, most notably the compact style of T S. Eliot, the frequent use of the lower-case for titles in the manner of e. e. cummings, and the racial consciousness of the Harlem Renaissance, especially as found in the work of Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes; but, of perhaps greater importance, she seems to be a direct descendant of the urban commitment and attitude of the “Chicago School’ of writing. For Brooks, setting goes beyond the Midwest with a focus on Chicago and concentrates on a small neglected comer of the city. Consequently, in the final analysis, she is not a carbon copy of any of the Chicago writers.She was appointed poet laureate of Illinois in 1968 and has been perhaps more active than many laureates. She has done much to bring poetry to the people through accessibility and public readings. In fact, she is one of our most visible American poets. Not only is she extremely active in the poetry workshop movement, but her classes and contests for young people are attempts to help inner-city children see “the poetry” in their lives. She has taught audiences that poetry is not some formal activity closed to all but the most perceptive.Rather, it is an art form within the reach and understanding of everybody–including the lowliest among us. Research more about this great American champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American activist for children’s rights.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American activist for children’s rights. She has been an advocate for disadvantaged Americans for her entire professional life. She is founder and president emerita of the Children’s Defense Fund. She influenced leaders such at Martin Luther King Jr. and Hillary Clinton.Today in our History – June 6, 1939- Children’s civil rights activist Marian Wright Edelman was born. She was the founder and president of the Children’s Defense Fund.Edelman attended Spelman College in Atlanta (B.A., 1960) and Yale University Law School (LL.B., 1963). After work registering African American voters in Mississippi, she moved to New York City as a staff attorney for the Legal Defense and Educational Fund of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).In 1964 Edelman returned to the South and became the first African American woman to pass the bar in Mississippi. In private practice, she took on civil rights cases and fought for funding of one of the largest Head Start programs in the country.She served as director of the Legal Defense and Educational Fund in Jackson, Mississippi (1964–68), and then moved to Washington, D.C., to start the Washington Research Project of the Southern Center for Public Policy, a public interest law firm.From 1971 to 1973 Edelman was the director of Harvard University’s Center for Law and Education, and in 1973 she founded and became president of the Children’s Defense Fund (CDF) in Washington, D.C. Under her leadership, the CDF became a highly effective organization in advocating children’s rights; in 2018 Edelman stepped down as president and became president emerita in the office of the founder. In 1996 she founded a similar organization, Stand for Children.Edelman’s publications included Children Out of School in America: A Report (1974), Portrait of Inequality: Black and White Children in America (1980), Families in Peril: An Agenda for Social Change (1987), The Measure of Our Success: A Letter to My Children and Yours (1992), and Guide My Feet: Meditations and Prayers on Loving and Working for Children (1995).Her honours include a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship (1985) and several humanitarian awards. In 2000 Edelman received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the country’s highest civilian award, and the Robert F. Kennedy Lifetime Achievement Award for her writings.In 2002 she published I’m Your Child, God: Prayers for Children and Teenagers. That same year, Edelman received the National Mental Health Association Tipper Gore Remember the Children Volunteer Award. In 2005 she published I Can Make a Difference: A Treasury to Inspire Our Children, and in 2008 she published The Sea Is So Wide and My Boat Is So Small: Charting a Course for the Next Generation. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies and make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American-Canadian anti-slavery activist, journalist, publisher, teacher, and lawyer.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American-Canadian anti-slavery activist, journalist, publisher, teacher, and lawyer. She was the first black woman publisher in North America and the first woman publisher in Canada. Shadd Cary edited The Provincial Freeman, established in 1853. Published weekly in southern Ontario, it advocated equality, integration and self-education for black people in Canada and the United States.Shadd Cary’s family was involved in the Underground Railroad assisting those fleeing slavery. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, her family relocated to Canada. She returned to the United States during the American Civil War where she recruited soldiers for the Union. She taught, went to Howard University Law School, and continued advocacy for civil rights for African Americans and women for the rest of her life.Today in our History – June 5, 1893 – Mary Ann Shadd Cary (October 9, 1823 – June 5, 1893) died.Mary Ann Shadd was born in Wilmington, Delaware, on October 9, 1823, the eldest of 13 children to Abraham Doras Shadd (1801–1882) and Harriet Burton Parnell, who were free African-Americans. Abraham D. Shadd was a grandson of Hans Schad, alias John Shadd, a native of Hesse-Cassel who had entered the United States serving as a Hessian soldier with the British Army during the French and Indian War. Hans Schad was wounded and left in the care of two African-American women, mother and daughter, both named Elizabeth Jackson. The Hessian soldier and the daughter were married in January 1756 and their first son was born six months later.A. D. Shadd was a son of Jeremiah Shadd, John’s younger son, who was a Wilmington butcher. Abraham Shadd was trained as a shoemaker and had a shop in Wilmington and later in the nearby town of West Chester, Pennsylvania. In both places he was active as a conductor on the Underground Railroad and in other civil rights activities, being an active member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, and, in 1833, named President of the National Convention for the Improvement of Free People of Colour in Philadelphia.Growing up, her family’s home frequently served as a refuge for fugitive slaves; however, when it became illegal to educate African-American children in the state of Delaware, the Shadd family moved to Pennsylvania, where Mary attended a Quaker Boarding School. In 1840, after being away at school, Mary Ann returned to East Chester and established a school for black children. She also later taught in Norristown, Pennsylvania, and New York City.Three years after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, A. D. Shadd moved his family to the United Canadas (Canada West), settling in North Buxton, Ontario. In 1858, he became one of the first black men to be elected to political office in Canada, when he was elected to the position of Counsellor of Raleigh Township, Ontario.In 1848, Frederick Douglass asked readers in his newspaper, The North Star, to offer their suggestions on what could be done to improve life for African-Americans. Mary Ann Shadd, then only 25 years of age, wrote to him to say, “We should do more and talk less.” She expressed her frustration with the many conventions that had been held to that date, such as those attended by her father, where speeches were made and resolutions passed about the evils of slavery and the need for justice for African-Americans. Yet little tangible improvement had resulted. Douglass published her letter in his paper.When the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 in the United States threatened to return free northern blacks and escaped slaves into bondage, Mary Ann Shadd and her brother Isaac Shadd moved to Canada, and settled in Windsor, Ontario, across the border from Detroit, where Mary Ann’s efforts to create free black settlements in Canada first began.While in Windsor, she founded a racially integrated school with the support of the American Missionary Association. Public education in Ontario was not open to black students at the time. Mary Ann offered daytime classes for children and youth, and evening classes for adults.An advocate for emigration, in 1852, Mary Ann Shadd published a pamphlet entitled A Plea for Emigration; or Notes of Canada West, in Its Moral, Social and Political Aspect: with Suggestions respecting Mexico, West Indies and Vancouver’s Island for the Information of Colored Emigrants. The pamphlet discussed the benefits of emigration, as well as the opportunities for blacks in the area.In 1853, Mary Ann Shadd founded an anti-slavery paper, called The Provincial Freeman. The paper’s slogan was “Devoted to antislavery, temperance and general literature.” It was published weekly, and the first issue was published in Toronto, Ontario, on March 24, 1853. It ran for four years, before financial challenges forced the paper to fold.Mary Ann was aware that her name would affect the number of people reading it, because of the gender expectations of the 19th century society. So, she persuaded Samuel Ringgold Ward, a black abolitionist who published several abolitionist newspapers, including Impartial Citizen, to help her publish it. She also enlisted the help of Rev. Alexander McArthur, a white clergyman. Their names were featured on the masthead, but Mary Ann was involved in all aspects of the paper.Isaac Shadd, Mary Ann’s brother, managed the daily business affairs of the newspaper. Isaac was a committed abolitionist, and would later host gatherings to plan the raid on Harper’s Ferry at his home.Mary Ann traveled widely in Canada and the United States to increase subscription to the paper, and to publicly solicit aid for runaway slaves. Because of the Fugitive Slave Act, these trips included significant risk to Mary Ann’s personal well-being; free blacks could be captured by bounty hunters seeking escaped slaves.As was typical in the black press, The Provincial Freeman played an important role by giving voice to the opinions of black Canadian anti-slavery activists.The impact of African-American newspapers from 1850–1860 was significant in the abolitionist movement. However, it was challenging to sustain publication. Publishers like Shadd undertook their work because of a commitment to education and advocacy, and used their newspapers as a means to influence opinion. They had to overcome financial, political and social challenges to keep their papers afloat.Carol B. Conaway writes in “Racial Uplift: The Nineteenth Century Thought of Black Newspaper Publisher Mary Ann Shadd Cary” that these newspapers shifted the focus from whites to blacks in an empowering way. She writes that whites read these newspapers to monitor the dissatisfaction level of the treatment of African Americans and to measure their tolerance for continued slavery in America.Black newspapers often modeled their newspapers on mainstream white publications. According to research conducted by William David Sloan in his various historical textbooks, the first newspapers were about four pages and had one blank page to provide a place for people to write their own information before passing it along to friends and relatives. He goes even farther to discuss how the newspapers during these early days were the center of information for society and culture.In 1854, Mary Ann Shadd changed the masthead to feature her own name, rather than McArthur and Ward. She also hired her sister to help edit the paper. There was intense criticism of the change, and Mary Ann was forced to resign the following year.Between 1855 and 1856, Shadd traveled in the United States as an anti-slavery speaker, advocating for full racial integration through education and self-reliance. In her speeches, she advised all blacks to insist on fair treatment and if all else failed, to take legal action.She sought to participate in the 1855 Philadelphia Colored Convention, but women had never been permitted to attend, and the assembly had to debate whether to let her sit as a delegate. Her advocacy of emigration made her a controversial figure and she was only admitted by a slim margin of 15 votes. According to Frederick Douglass’s Paper, although she gave a speech at the Convention advocating for emigration, she was so well-received that the delegates voted to give her ten more minutes to speak. However, her presence at the Convention was largely elided from the minutes, likely because she was a woman.In 1856, she married Thomas F. Cary, a Toronto barber who was also involved with the Provincial Freeman. She had a daughter named Sarah and a son named Linton.After her husband died in 1860, Shadd Cary and her children returned to the United States. During the Civil War, at the behest of the abolitionist Martin Delany, she served as a recruiting officer to enlist black volunteers for the Union Army in the state of Indiana.After the Civil War, she taught in black schools in Wilmington. She then returned to Washington, D.C., with her daughter, and taught for fifteen years in the public schools. She then attended Howard University School of Law and graduated at the age of 60 in 1883, becoming only the second black woman in the United States to earn a law degree.She wrote for the newspapers National Era and The People’s Advocate and in 1880, organized the Colored Women’s Progressive Franchise.Shadd Cary joined the National Woman Suffrage Association, working alongside Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton for women’s suffrage, testifying before the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives, and becoming the first African-American woman to vote in a national election.She died in Washington, D.C., on June 5, 1893, from stomach cancer. She was interred at Columbian Harmony Cemetery.In the United States, Shadd Cary’s former residence in the U Street Corridor of Washington, DC, was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976. In 1987 she was designated a Women’s History Month Honoree by the National Women’s History Project. In 1998, Shadd Cary was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.In Canada, she was designated a Person of National Historic Significance, with a plaque from the national Historic Sites and Monuments Board placed in Chatham, Ontario. There, Ontario provincial plaques also honor her and her newspaper, The Provincial Freeman. In Toronto, a Heritage Toronto plaque marks where she published the Provincial Freeman while living in the city from 1854 to 1855.Shadd Cary is featured in Canada’s citizenship test study guide, released in 2009.In 1985 Mary Shadd Public School was opened in Scarborough Ontario Canada, in the town of Malvern, and was later enlarged in 1992. The school motto “Free to be…the best of me” and school anthem “We’re on the right track…Mary Shadd” are tributes to Mary Ann Shadd, after whom the school was named.In 2018 the New York Times published a belated obituary for her.Shadd’s 197th birthday was observed with a Google Doodle on October 9, 2020, appearing across Canada, the United States, Latvia, Senegal, Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania, and South Africa.The Mary Ann Shadd Cary Post Office, named that in 2021, is at 500 Delaware Avenue, Suite 1, in Wilmington, Delaware. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a United States Navy officer.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a United States Navy officer. He was the first African American in the U.S. Navy to serve aboard a fighting ship as an officer, the first to command a Navy ship, the first fleet commander, and the first to become a flag officer, retiring as a vice admiral.Today in our History – June 4, 1922 – Samuel L. Gravely is born.Gravely was born on June 4, 1922 in Richmond, Virginia, the oldest of five children of Mary George Gravely and postal worker Samuel L. Gravely Sr. He attended Virginia Union University but left before graduating to join the Naval Reserve in 1942. He had attempted to enlist in the U.S. Army in 1940 but was turned away due to a supposed heart murmur. After receiving basic training at Naval Station Great Lakes, Illinois, Gravely entered the V-12 Navy College Training Program at the University of California, Los Angeles. Upon graduating from UCLA, he completed Midshipmen’s School at Columbia University and was commissioned an ensign on November 14, 1944. His commission came only eight months after the “Golden Thirteen” became the first African-American officers in the U.S. Navy. Gravely began his seagoing career as the only black officer aboard the submarine chaser USS PC-1264, which was one of two U.S. Navy ships (the other being USS Mason (DE-529)) with a predominantly black enlisted crew. Before June 1, 1942, African Americans could only enlist in the Navy as messmen; PC-1264 and Mason were intended to test the ability of African Americans to perform general Navy service. For the remainder of World War II, PC-1264 conducted patrols and escort missions along the east coast of the U.S. and south to the Caribbean. In 1946, Gravely was released from active duty, remaining in the Naval Reserve. He married schoolteacher Alma Bernice Clark later that year; the couple went on to raise three children, Robert, David, and Tracey. He returned to his hometown of Richmond and re-enrolled at Virginia Union University, graduating in 1948 with a degree in history and then working as a railway postal clerk. Gravely was recalled to active duty in 1949 and worked as a recruiter in Washington, D.C. before holding both shore and sea assignments during the Korean War. During that time he served on the USS Iowa as a communications officer. He transferred from the Reserve to the regular Navy in 1955 and began to specialize in naval communications. Many of Gravely’s later career achievements represented “firsts” for African Americans. From 15 February 1961 to 21 October 1961, he served as the first African-American officer to command a U.S. Navy ship, the USS Theodore E. Chandler (DD-717) (Robert Smalls had briefly commanded a Navy ship in the American Civil War, although he was a civilian, not a Navy officer). He also commanded of the radar picket destroyer escort USS Falgout (DE-324) from January 1962 to June 1963. During the Vietnam War he commanded the destroyer USS Taussig (DD-746) as it performed plane guard duty and gunfire support off the coast of Vietnam in 1966, making him the first African American to lead a ship into combat. In 1967 he became the first African American to reach the rank of captain, and in 1971 the first to reach rear admiral. At the time of his promotion to rear admiral, he was in command of the guided missile frigate USS Jouett (DLG-29). Gravely commanded Cruiser-Destroyer Group 2. He was later named the Director of Naval Communications. From 1976 to 1978, he commanded the Third Fleet based in Hawaii, then transferred to Virginia to direct the Defense Communications Agency until his retirement in 1980. Gravely’s military decorations include the Legion of Merit, Bronze Star Medal, Meritorious Service Medal and Navy Commendation Medal. He was also awarded the World War II Victory Medal, the Korean Service Medal with two service stars, the United Nations Korea Medal, and the Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation. Following his military retirement, Gravely settled in rural Haymarket, Virginia, and worked as a consultant. After suffering a stroke, Gravely died at the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, on October 22, 2004. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.In Richmond, the street on which Gravely grew up was renamed “Admiral Gravely Boulevard” in 1977. Samuel L. Gravely, Jr. Elementary School in Haymarket, Virginia was named after him in 2008. The destroyer USS Gravely (DDG-107), commissioned in 2010, was named in his honor. Vice Admiral Gravely is honored annually in San Pedro, California, aboard Battleship Iowa, at the Gravely Celebration Experience. Each year the organization honors trailblazers exemplifying VADM Gravely’s leadership and service with the Leadership & Service Award. An essay competition for U.S. History high school students that explores VADM Gravely’s motto: Education, Motivation, Perseverance is affiliated with the annual event. Research more about this great America Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was was an American Roman Catholic priest and the second bishop of Portland, Maine.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was was an American Roman Catholic priest and the second bishop of Portland, Maine. He was the first Black Catholic priest and bishop in the United States (though he passed for White).Born in Georgia to a mixed-race slave mother and Irish immigrant father, he was ordained in 1854 and consecrated in 1875; knowledge of his African ancestry was largely restricted to his mentors in the Church. (Augustus Tolton, a former slave who was publicly known to be African-American when ordained in 1886, is for that reason sometimes credited as the first African-American Catholic priest rather than Healy.)Healy was one of nine mixed-race siblings of the Catholic Healy family of Georgia who survived to adulthood and achieved many “firsts” in United States history; his brothers Patrick and Alexander also became Catholic priests.James is credited with greatly expanding the Catholic church in Maine at a time of increased Irish immigration, and he also served Abenaki people and many parishioners of French Canadian descent who were traditionally Catholic. He spoke both English and French.Today in our History – June 2, 1975- James A. Healy became the first Roman Catholic bishop and consecrated at a cathedral in Portland, Maine.Healy was one of 10 children born on a Georgia cotton plantation to an Irish immigrant and his common-law wife, a mixed-race slave. Because Healy and his siblings were legally considered illegitimate and slaves, they were barred from attending school in the state, and their parents were forced to send the boys to schools in the North. After encountering racial prejudice at their first school in Long Island, New York,Healy and his brothers completed their education in Massachusetts. In 1849 Healy was the valedictorian of the first graduating class of Holy Cross College. His brother Patrick, who also attended Holy Cross, became the first African American to earn a Ph.D.; he was later president of Georgetown University.After college Healy attended seminary in Montreal and in Paris and was ordained a priest in 1854 (see Researcher’s Note). He did mission work in Boston, where he opposed state anti-Catholic laws. He then served as chancellor of the diocese and, during the Civil War, as secretary to the bishop. He was made pastor of St. James Church in Boston in 1866 and was appointed bishop of Portland by Pope Pius IX in 1875.As bishop (1875–1900), he faced anti-Catholic sentiment but doubled the Catholic population of his diocese, which included Maine and New Hampshire, and increased the number of priests significantly; this growth led to the division of the diocese in two in 1885. During his reign, Healy established numerous churches, schools, convents, and welfare institutions. A tireless advocate for Civil War widows and orphans, he purchased part of an island near Portland to use as a vacation site for children.He was a leader of the American bishops who proposed three decrees that were approved in 1884 by the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore, which was empowered to legislate for all ecclesiastical provinces in the country. In recognition of his support for Native Americans, Healy was made a consultant to the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. On his 25th anniversary as bishop, he was named assistant to the papal throne, a position only one step below cardinal in the church hierarchy. Although an advocate for the less fortunate, Healy never took up specifically African American issues, and he even turned down invitations to speak to African American Catholic groups. Research more about this great American Vhampion and share it with you babies. Make it a champion day!