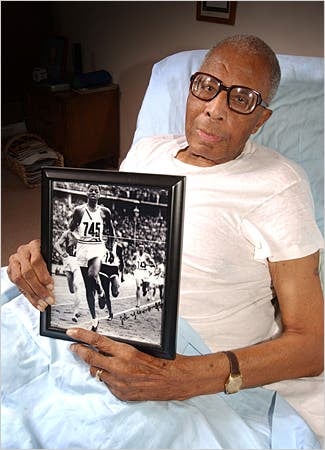

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American middle-distance runner, winner of the 800 m event at the 1936 Summer Olympics. I learned about him in Junior High School in Trenton, NJ and decided to run the 800 in his honor and the Long Jump for what Jesse Owens did. I met him in Trenton, N.J. in 1968, when he was living in Highstown, N.J.Woodruff was only a freshman at the University of Pittsburgh in 1936 when he placed second at the National AAU meet and first at the Olympic Trials (in the heat 1:49.9; WR 1:49.![]() , earning a spot on the U.S. Olympic team. Woodruff was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.Despite his inexperience, he was the favorite in the Olympic 800 meter run, and he did not disappoint. In one of the most exciting races in Olympic history, Woodruff became boxed in by other runners and was forced to stop running. He then came from behind to win in 1:52.9. The New York Times described the race:He remembers the anguish of his Olympic race: “Phil Edwards, the Canadian doctor, set the pace, and it was very slow. On the first lap, I was on the inside, and I was trapped. I knew that the rules of running said if I tried to break out of a trap and fouled someone, I would be disqualified. At that point, I didn’t think I could win, but I had to do something.”Woodruff was a 21-year-old college freshman, an unsophisticated and, at 6 feet 3 inches (1.91 m), an ungainly runner. But he was a fast thinker, and he made a quick decision.”I didn’t panic,” he said. “I just figured if I had only one opportunity to win, this was it. I’ve heard people say that I slowed down or almost stopped. I didn’t almost stop. I stopped, and everyone else ran around me.”Then, with his stride of almost 10 feet (3.0 m), Woodruff ran around everyone else. He took the lead, lost it on the backstretch, but regained it on the final turn and won the gold medal.During a career that was curtailed by World War II, Woodruff won one AAU (Amateur Athletic Union) title in 800 m in 1937 and won both 440 yd (400 m) and 880 yd (800 m) IC4A titles from 1937 to 1939. Woodruff also held a share of the world 4×880 yd relay record while competing with the national team.Woodruff graduated from the University of Pittsburgh in 1939, with a major in sociology. While at the University of Pittsburgh Woodruff became a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity. and then earned a master’s degree in the same field from New York University in 1941.He entered military service in 1941 as a second lieutenant and was discharged as a captain in 1945. He re-entered military service during the Korean War, and left in 1957 as a lieutenant colonel. He was the battalion commander of the 369th Artillery, later the 569 Transportation Battalion New York Army National Guard.In later years Woodruff lived in New Rochelle in Westchester County, New York and in Hightstown, New Jersey. He coached young athletes and officiated at local and Madison Garden track meets. Woodruff also worked as a teacher in New York City, a special investigator for the New York Department of Welfare, a recreation center director for the New York City Police Athletic League, a parole officer for the state of New York, a salesperson for Schieffelin and Co. and an assistant to the Center Director for Edison Job Corps Center in New Jersey.In the late 1990s John, with his wife Rose, retired to Fountain Hills, Arizona residing at Fountain View Village retirement community. Woodruff’s last public appearance was on April 15, 2007 when he, along with the members of the Tuskegee Airmen, was honored by the Arizona Diamondbacks by throwing out the first pitch. John Woodruff is buried at Crown Hill Cemetery, Indianapolis (section 46, lot 86).Each year, a 5-kilometer road race is held in Connellsville to honor Woodruff.Today in our History – October 30, 2007 – John Youie “Long John” Woodruff died.John Woodruff was the last surviving U.S. gold-medalist from the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. The 21-year-old freshman from the University of Pittsburgh won the middle distance 800-meter race on August 1, 1936 and he did it with a daring maneuver that carried him from dead last to victory.Along with the four gold medals won that year by Jesse Owens, John Woodruff’s victory helped challenge notions of Aryan racial supremacy before a stadium of spectators that included Adolph Hitler and other leaders of Germany’s Nazi regime.John Woodruff went on to win championships and set time records in numerous races while earning degrees in sociology from the University of Pittsburgh and New York University. After serving as an officer in the army during World War II, the sociologist worked for public agencies including several that helped disadvantaged youth. John Woodruff is the grandson of Virginia slaves and the son of a steelworker. He has two children and lives in Arizona with his second wife RoseJohn Woodruff was born on July 5, 1915 in Connellsville, Pennsylvania, a small town in the heart of steelmaking country. Though the town was prosperous John’s parents were poor. His father Silas, the son of Virginia slaves, worked for the H.C. Frick Coke Company. His mother, Sarah, was a spiritual woman who gave birth to 12 children, six of whom died in infancy. John was especially close to his mother and to an older sister Margaret, who resembled her.Hard work was valued more than school in the Woodruff household. So neither his father, who had an eighth grade education, nor his mother, who had a second grade education, took much notice when their next to youngest child, John, became an avid reader. John recalls startling his own second grade teacher by finishing books several years beyond his level. He also remembers signing his own report cards because his father was functionally illiterate.By the time John reached high school the Great Depression had brought hard times to Connellsville. When some of John’s white classmates dropped out to take factory jobs John tried to do the same. But the 16-year-old was told the company was not hiring Negroes so he went back to school. He says that the experience marked the one time discrimination worked to his benefit.In the 11th grade John made the football team. Each practice wound up with a run up to the cemetery and back to the field. At just over six-feet-three-inches tall, John had a nine-foot running stride that would later earn him the nickname ‘Long John Woodruff’. That stride instantly grabbed the attention of assistant football coach and track coach Joseph Larew.Unfortunately the only thing John’s mother noticed was that her son was getting home from school too late for his chores. She demanded that he quit. But the track team required less time than football so in the spring coach Larew convinced John to sign up. In his first competition John won both the 880-yard and one-mile runs.At a meet in Morgantown, West Virginia he met Ohio State’s star runner Jesse Owens who became a friend and inspiration – putting John on track to becoming a star athlete and the first – and only – member of his family to finish high school. (John notes that his sister Margaret eventually earned her GED and became a nurse.)Unfortunately his mother would not live to see her son graduate. In 1935 she died of cancer at the age of 59. Despite the personal tragedy, John Woodruff set school, county, district, and state records and broke the national school mile record with a time of 4:23.4. He also scored an athletic scholarship to the University of Pittsburgh.John credits Pitt track coach Carl Olson with helping him get to college but once there campus life posed severe financial hardships for the 20-year-old. He recalls arriving with just 25 cents in his pocket and living at a YMCA infested with bedbugs. To earn money and qualify for meal benefits he took assorted jobs including cleaning the athletic facilities and working on the campus grounds.He planned to study physical education but switched to Sociology and History due to his interest in people his love of books. Meanwhile, on the field his freshman year, he swept up gold medals at the Penn Relays and National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) meets, prompting Coach Olson to invite John to try out for the 1936 Summer Olympic Games in Berlin, Germany. He landed a spot on the U.S. men’s track and field team which included several other African-Americans including Jesse Owens.At the time America’s participation in the games was in question. John recalls, “There was some talk about the Olympics being boycotted because of what Hitler was doing to the Jewish people in Germany. But it was never discussed amongst team members.We heard something about it, but we never discussed it. We weren’t interested in the politics you see at all we were only interested in going to Germany and winning.” In July he celebrated his twenty-first birthday and then sailed to Germany. Despite being nervous about his first voyage overseas, teammates were drawn to John. He won their respect and forged friendships that would last a lifetime.At the games John won the semi-finals of the 800-meter race by 20 yards. But in the final event he made a tactical mistake – a mistake he turned into an unforgettable moment of triumph. He has recounted the story many times: “Phil Edwards (a five-time Olympic medalist from Canada) jumped right in front and set a very, very slow pace.I decided due to my lack of experience I would follow him. … The pace was so slow, and all the runners crowded right around me…I had enough experience to know if I tried to get out of the trap, I was going to be disqualified. So I moved out into the third lane, and I let all the runners precede me. That’s what made the race very outstanding.I actually started the race twice.” Restarting from a dead stop behind the other contenders John passed them all. His winning time of 1:52:9 led some to wonder how much faster it might have been had he not been caught in the pack. The New York Herald-Tribune called it the “most daring move seen on a track.”John has said, “I didn’t know I was going to win that race. I really didn’t. I just took advantage of the opportunity to get there to give me a chance to win it.” Woodruff became the first American to win the Gold in the 800-meter race in more than 20 years. He still remembers the elation he felt on the victory stand. Contrary to some reports that Hitler and the Germans overtly snubbed the black athletes, John says he was treated extremely well especially by the public.Following a tour of Europe with teammates to compete in local meets, Connellsville threw John a homecoming parade. The town presented him with a gold watch (later stolen) and John gave the town a small German oak tree that had been presented to each medal winner. Not many of the trees had survived the trip home and time spent in the hands of agricultural inspectors. But John had taken pains to reclaim his sapling and to see it that was nursed back to health.Once he returned to college for his sophomore year his gratitude and elation met with the sobering realities of racism in America. First he was excluded from competing at a track meet at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis. “Navy refused to allow Pitt to come if they brought me. I could not go because I was black.”And, when he did travel with the team, the star athlete was routinely required to stay apart from the whites. But the biggest blow came in 1937 when Woodruff says biased officials deprived him of a world record at the Greater Texas and Pan American Exposition games. The trip south started badly with Pitt’s black athletes having to threaten to withdraw from competition to gain access to the train’s dining car.And once in Dallas, they were bused to a YMCA to sleep on cots in a gym. Then John ran the fastest race of his life in the 880-yard track event, beating world record holder Elroy Robinson with a time of 1:47.8. But officials who had certified the measurement of the track before the race, re-measured it and found to be six feet short. John was devastated and has said, “You know what happened. Those boys got their heads together and decided they weren’t going to give a black man a white man’s record.”Though bitter, he continued to compete, maintaining his amateur status while earning his undergraduate degree. In relay after relay he racked up wins and set records. He became the first athlete to ever anchor three championship relays in a year in 1938, and did it again in 1939.He is especially proud of anchoring the Sprint Medley Relays held in Philadelphia that set a new world record in 1939, a stat that is recorded on the back wall of the stadium at Franklin Field. Author Jim Kriek once summed up his varsity accomplishments by saying they, “included three national collegiate half-mile championships, three IC4A championships in the 440 and 880, a new American record in the 800-meters, a world record half-mile run at the Cotton Bowl, in Dallas, Texas, national AAU half-mile championships, and various school and state honors.”On June 7, 1940 he set an American record in the 800-meter race1:48:60. That same year he graduated from the University of Pittsburgh, and went on New York University, earning a master’s degree in Sociology in 1941.If not for World War II he may have become a university professor and participated in another Olympic competition. Instead he entered the army as a Second Lieutenant and the following year he married. Among the guests at John’s 1942 wedding to Hattie Davis was good friend Jesse Owens. The Woodruff’s had two children, Randelyn (Randy) Gilliam, now a retired teacher living in Chicago and John, Jr. now a trial attorney in New York.During the war John rose to the rank of Lt. Colonel and was discharged from active duty in 1945. He returned to New York and held jobs with government agencies as a parole officer, teacher and special investigator for the New York Department of Welfare. He also worked for the New York City Children’s Aid Society and was once the Recreation Center Director for the New York City Police Athletic League.In 1968, John accepted a job in Indiana to manage residents enrolled in the U.S. Job Corps, a federal anti-poverty program aimed at helping at-risk youth. Ultimately the move split the Woodruff family and led to divorce. In 1970, John married his current wife Rose, and they relocated with the Job Corps to Hightstown, New Jersey. John retired from the Jobs Corps later that year.In 1972 John returned to Germany to watch the Munich Olympic Games as a special guest of the government. And for many years he made the annual trip to Philadelphia officiate at the Penn Relays. For generations of runners he has served as a role model – and for many, as a friend. Until their deaths John maintained relationships with fellow athletes Jesse Owens and Ralph Metcalfe, a runner once known as the world’s fastest human being. And he still keeps in touch with 1936 Olympian Margaret Bergmann Lambert, a German high jumper excluded from competition because she was Jewish.Another close friend is Herb Douglas, a 1948 Olympic long jump bronze medalist who calls John Woodruff his mentor. John also inspired many unknown to him personally. For years he was a popular speaker at the Peddie School near his New Jersey home advising students to, “get an education, have courage and never give up.”In the 1970’s John Woodruff donated memorabilia from his track career to his high school and today his Olympic gold medal hangs in the library at the University of Pittsburgh. There are numerous other honors too.The annual John Woodruff Day in Connellsville, Pennsylvania includes a 5k run and walk and scholarships that give new generations opportunities to advance their education. And in 1994, he received the most votes of any athlete selected for the inaugural class of the Penn Relays Wall of Fame.John remains proud of his achievements and says he has no regrets even though he has paid a heavy price for the years of high impact running. After enduring spine surgery, heart problems and a hip replacement, poor circulation caused doctors to amputate both of his legs above the knees in 2001.But his spirit has not dimmed. He remains in touch with friends and an extended family that now includes five grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. And he continues to read. His favorite books are the Bible, and novels about great historical figures including Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Albert Einstein.Perhaps the perfect metaphor for his life is the fate of the tree that he carried back from Berlin in 1936. It now stands 78-feet tall. It’s become known as the ‘Woodruff Oak’ and by some accounts it’s the only one of those commemorative gifts still alive and producing fertile acorns.Like the man himself it is a towering presence at Connellsville High and a symbol of strength and resilience that represents John Woodruff’s legacy. Recearch more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

, earning a spot on the U.S. Olympic team. Woodruff was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.Despite his inexperience, he was the favorite in the Olympic 800 meter run, and he did not disappoint. In one of the most exciting races in Olympic history, Woodruff became boxed in by other runners and was forced to stop running. He then came from behind to win in 1:52.9. The New York Times described the race:He remembers the anguish of his Olympic race: “Phil Edwards, the Canadian doctor, set the pace, and it was very slow. On the first lap, I was on the inside, and I was trapped. I knew that the rules of running said if I tried to break out of a trap and fouled someone, I would be disqualified. At that point, I didn’t think I could win, but I had to do something.”Woodruff was a 21-year-old college freshman, an unsophisticated and, at 6 feet 3 inches (1.91 m), an ungainly runner. But he was a fast thinker, and he made a quick decision.”I didn’t panic,” he said. “I just figured if I had only one opportunity to win, this was it. I’ve heard people say that I slowed down or almost stopped. I didn’t almost stop. I stopped, and everyone else ran around me.”Then, with his stride of almost 10 feet (3.0 m), Woodruff ran around everyone else. He took the lead, lost it on the backstretch, but regained it on the final turn and won the gold medal.During a career that was curtailed by World War II, Woodruff won one AAU (Amateur Athletic Union) title in 800 m in 1937 and won both 440 yd (400 m) and 880 yd (800 m) IC4A titles from 1937 to 1939. Woodruff also held a share of the world 4×880 yd relay record while competing with the national team.Woodruff graduated from the University of Pittsburgh in 1939, with a major in sociology. While at the University of Pittsburgh Woodruff became a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity. and then earned a master’s degree in the same field from New York University in 1941.He entered military service in 1941 as a second lieutenant and was discharged as a captain in 1945. He re-entered military service during the Korean War, and left in 1957 as a lieutenant colonel. He was the battalion commander of the 369th Artillery, later the 569 Transportation Battalion New York Army National Guard.In later years Woodruff lived in New Rochelle in Westchester County, New York and in Hightstown, New Jersey. He coached young athletes and officiated at local and Madison Garden track meets. Woodruff also worked as a teacher in New York City, a special investigator for the New York Department of Welfare, a recreation center director for the New York City Police Athletic League, a parole officer for the state of New York, a salesperson for Schieffelin and Co. and an assistant to the Center Director for Edison Job Corps Center in New Jersey.In the late 1990s John, with his wife Rose, retired to Fountain Hills, Arizona residing at Fountain View Village retirement community. Woodruff’s last public appearance was on April 15, 2007 when he, along with the members of the Tuskegee Airmen, was honored by the Arizona Diamondbacks by throwing out the first pitch. John Woodruff is buried at Crown Hill Cemetery, Indianapolis (section 46, lot 86).Each year, a 5-kilometer road race is held in Connellsville to honor Woodruff.Today in our History – October 30, 2007 – John Youie “Long John” Woodruff died.John Woodruff was the last surviving U.S. gold-medalist from the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. The 21-year-old freshman from the University of Pittsburgh won the middle distance 800-meter race on August 1, 1936 and he did it with a daring maneuver that carried him from dead last to victory.Along with the four gold medals won that year by Jesse Owens, John Woodruff’s victory helped challenge notions of Aryan racial supremacy before a stadium of spectators that included Adolph Hitler and other leaders of Germany’s Nazi regime.John Woodruff went on to win championships and set time records in numerous races while earning degrees in sociology from the University of Pittsburgh and New York University. After serving as an officer in the army during World War II, the sociologist worked for public agencies including several that helped disadvantaged youth. John Woodruff is the grandson of Virginia slaves and the son of a steelworker. He has two children and lives in Arizona with his second wife RoseJohn Woodruff was born on July 5, 1915 in Connellsville, Pennsylvania, a small town in the heart of steelmaking country. Though the town was prosperous John’s parents were poor. His father Silas, the son of Virginia slaves, worked for the H.C. Frick Coke Company. His mother, Sarah, was a spiritual woman who gave birth to 12 children, six of whom died in infancy. John was especially close to his mother and to an older sister Margaret, who resembled her.Hard work was valued more than school in the Woodruff household. So neither his father, who had an eighth grade education, nor his mother, who had a second grade education, took much notice when their next to youngest child, John, became an avid reader. John recalls startling his own second grade teacher by finishing books several years beyond his level. He also remembers signing his own report cards because his father was functionally illiterate.By the time John reached high school the Great Depression had brought hard times to Connellsville. When some of John’s white classmates dropped out to take factory jobs John tried to do the same. But the 16-year-old was told the company was not hiring Negroes so he went back to school. He says that the experience marked the one time discrimination worked to his benefit.In the 11th grade John made the football team. Each practice wound up with a run up to the cemetery and back to the field. At just over six-feet-three-inches tall, John had a nine-foot running stride that would later earn him the nickname ‘Long John Woodruff’. That stride instantly grabbed the attention of assistant football coach and track coach Joseph Larew.Unfortunately the only thing John’s mother noticed was that her son was getting home from school too late for his chores. She demanded that he quit. But the track team required less time than football so in the spring coach Larew convinced John to sign up. In his first competition John won both the 880-yard and one-mile runs.At a meet in Morgantown, West Virginia he met Ohio State’s star runner Jesse Owens who became a friend and inspiration – putting John on track to becoming a star athlete and the first – and only – member of his family to finish high school. (John notes that his sister Margaret eventually earned her GED and became a nurse.)Unfortunately his mother would not live to see her son graduate. In 1935 she died of cancer at the age of 59. Despite the personal tragedy, John Woodruff set school, county, district, and state records and broke the national school mile record with a time of 4:23.4. He also scored an athletic scholarship to the University of Pittsburgh.John credits Pitt track coach Carl Olson with helping him get to college but once there campus life posed severe financial hardships for the 20-year-old. He recalls arriving with just 25 cents in his pocket and living at a YMCA infested with bedbugs. To earn money and qualify for meal benefits he took assorted jobs including cleaning the athletic facilities and working on the campus grounds.He planned to study physical education but switched to Sociology and History due to his interest in people his love of books. Meanwhile, on the field his freshman year, he swept up gold medals at the Penn Relays and National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) meets, prompting Coach Olson to invite John to try out for the 1936 Summer Olympic Games in Berlin, Germany. He landed a spot on the U.S. men’s track and field team which included several other African-Americans including Jesse Owens.At the time America’s participation in the games was in question. John recalls, “There was some talk about the Olympics being boycotted because of what Hitler was doing to the Jewish people in Germany. But it was never discussed amongst team members.We heard something about it, but we never discussed it. We weren’t interested in the politics you see at all we were only interested in going to Germany and winning.” In July he celebrated his twenty-first birthday and then sailed to Germany. Despite being nervous about his first voyage overseas, teammates were drawn to John. He won their respect and forged friendships that would last a lifetime.At the games John won the semi-finals of the 800-meter race by 20 yards. But in the final event he made a tactical mistake – a mistake he turned into an unforgettable moment of triumph. He has recounted the story many times: “Phil Edwards (a five-time Olympic medalist from Canada) jumped right in front and set a very, very slow pace.I decided due to my lack of experience I would follow him. … The pace was so slow, and all the runners crowded right around me…I had enough experience to know if I tried to get out of the trap, I was going to be disqualified. So I moved out into the third lane, and I let all the runners precede me. That’s what made the race very outstanding.I actually started the race twice.” Restarting from a dead stop behind the other contenders John passed them all. His winning time of 1:52:9 led some to wonder how much faster it might have been had he not been caught in the pack. The New York Herald-Tribune called it the “most daring move seen on a track.”John has said, “I didn’t know I was going to win that race. I really didn’t. I just took advantage of the opportunity to get there to give me a chance to win it.” Woodruff became the first American to win the Gold in the 800-meter race in more than 20 years. He still remembers the elation he felt on the victory stand. Contrary to some reports that Hitler and the Germans overtly snubbed the black athletes, John says he was treated extremely well especially by the public.Following a tour of Europe with teammates to compete in local meets, Connellsville threw John a homecoming parade. The town presented him with a gold watch (later stolen) and John gave the town a small German oak tree that had been presented to each medal winner. Not many of the trees had survived the trip home and time spent in the hands of agricultural inspectors. But John had taken pains to reclaim his sapling and to see it that was nursed back to health.Once he returned to college for his sophomore year his gratitude and elation met with the sobering realities of racism in America. First he was excluded from competing at a track meet at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis. “Navy refused to allow Pitt to come if they brought me. I could not go because I was black.”And, when he did travel with the team, the star athlete was routinely required to stay apart from the whites. But the biggest blow came in 1937 when Woodruff says biased officials deprived him of a world record at the Greater Texas and Pan American Exposition games. The trip south started badly with Pitt’s black athletes having to threaten to withdraw from competition to gain access to the train’s dining car.And once in Dallas, they were bused to a YMCA to sleep on cots in a gym. Then John ran the fastest race of his life in the 880-yard track event, beating world record holder Elroy Robinson with a time of 1:47.8. But officials who had certified the measurement of the track before the race, re-measured it and found to be six feet short. John was devastated and has said, “You know what happened. Those boys got their heads together and decided they weren’t going to give a black man a white man’s record.”Though bitter, he continued to compete, maintaining his amateur status while earning his undergraduate degree. In relay after relay he racked up wins and set records. He became the first athlete to ever anchor three championship relays in a year in 1938, and did it again in 1939.He is especially proud of anchoring the Sprint Medley Relays held in Philadelphia that set a new world record in 1939, a stat that is recorded on the back wall of the stadium at Franklin Field. Author Jim Kriek once summed up his varsity accomplishments by saying they, “included three national collegiate half-mile championships, three IC4A championships in the 440 and 880, a new American record in the 800-meters, a world record half-mile run at the Cotton Bowl, in Dallas, Texas, national AAU half-mile championships, and various school and state honors.”On June 7, 1940 he set an American record in the 800-meter race1:48:60. That same year he graduated from the University of Pittsburgh, and went on New York University, earning a master’s degree in Sociology in 1941.If not for World War II he may have become a university professor and participated in another Olympic competition. Instead he entered the army as a Second Lieutenant and the following year he married. Among the guests at John’s 1942 wedding to Hattie Davis was good friend Jesse Owens. The Woodruff’s had two children, Randelyn (Randy) Gilliam, now a retired teacher living in Chicago and John, Jr. now a trial attorney in New York.During the war John rose to the rank of Lt. Colonel and was discharged from active duty in 1945. He returned to New York and held jobs with government agencies as a parole officer, teacher and special investigator for the New York Department of Welfare. He also worked for the New York City Children’s Aid Society and was once the Recreation Center Director for the New York City Police Athletic League.In 1968, John accepted a job in Indiana to manage residents enrolled in the U.S. Job Corps, a federal anti-poverty program aimed at helping at-risk youth. Ultimately the move split the Woodruff family and led to divorce. In 1970, John married his current wife Rose, and they relocated with the Job Corps to Hightstown, New Jersey. John retired from the Jobs Corps later that year.In 1972 John returned to Germany to watch the Munich Olympic Games as a special guest of the government. And for many years he made the annual trip to Philadelphia officiate at the Penn Relays. For generations of runners he has served as a role model – and for many, as a friend. Until their deaths John maintained relationships with fellow athletes Jesse Owens and Ralph Metcalfe, a runner once known as the world’s fastest human being. And he still keeps in touch with 1936 Olympian Margaret Bergmann Lambert, a German high jumper excluded from competition because she was Jewish.Another close friend is Herb Douglas, a 1948 Olympic long jump bronze medalist who calls John Woodruff his mentor. John also inspired many unknown to him personally. For years he was a popular speaker at the Peddie School near his New Jersey home advising students to, “get an education, have courage and never give up.”In the 1970’s John Woodruff donated memorabilia from his track career to his high school and today his Olympic gold medal hangs in the library at the University of Pittsburgh. There are numerous other honors too.The annual John Woodruff Day in Connellsville, Pennsylvania includes a 5k run and walk and scholarships that give new generations opportunities to advance their education. And in 1994, he received the most votes of any athlete selected for the inaugural class of the Penn Relays Wall of Fame.John remains proud of his achievements and says he has no regrets even though he has paid a heavy price for the years of high impact running. After enduring spine surgery, heart problems and a hip replacement, poor circulation caused doctors to amputate both of his legs above the knees in 2001.But his spirit has not dimmed. He remains in touch with friends and an extended family that now includes five grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. And he continues to read. His favorite books are the Bible, and novels about great historical figures including Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Albert Einstein.Perhaps the perfect metaphor for his life is the fate of the tree that he carried back from Berlin in 1936. It now stands 78-feet tall. It’s become known as the ‘Woodruff Oak’ and by some accounts it’s the only one of those commemorative gifts still alive and producing fertile acorns.Like the man himself it is a towering presence at Connellsville High and a symbol of strength and resilience that represents John Woodruff’s legacy. Recearch more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!