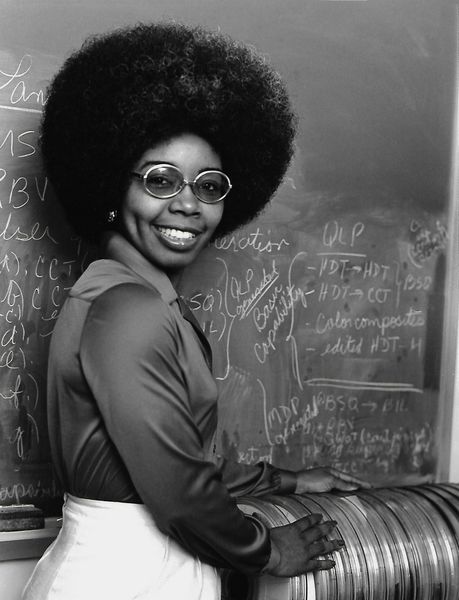

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American scientist and inventor. She invented the illusion transmitter, for which she received a patent in 1980. She was responsible for developing the digital media formats image processing systems used in the early years of the Landsat program.Today in our History – October 21, 1980 – Valerie Thomas invented the Illusion Transmitter.Thomas was interested in science as a child, after observing her father tinkering with the television and seeing the mechanical parts inside the TV. At the age of eight, she read The Boys First Book on Electronics, which sparked her interest in a career in science. Her father would not help her with the projects in the book, despite his own interest in electronics. At the all-girls school she attended, she was not encouraged to pursue science and mathematics courses, though she did manage to take a physics course.Thomas did not have a lot of support as a young child; her parents did not fight for her right to study a STEM curriculum, but she did have a few teachers who fought for her at a young age. She attended Morgan State University, where she was one of two women majoring in physics. Thomas excelled in her mathematics and science courses at Morgan State University. She graduated with highest honors in 1964 with a degree in physics went on to work for NASA.In 1976, she attended a scientific seminar where she viewed an exhibit that demonstrated an illusion. The exhibit used concave mirrors to fool the viewer into believing that a light bulb was glowing even after it had been unscrewed from its socket. She was so amazed by what she saw at this seminar that she wanted to start creating this on her own. Later that year she started to experiment with flat and concave mirrors. The flat mirrors produce a reflection of an object that seems to be behind the glass. The concave mirrors reflect objects so they appear in front of the glass, producing a three-dimensional illusion.In 1964, Thomas began working for NASA as a data analyst. She developed real-time computer data systems to support satellite operations control centers (1964–1970) and oversaw the creation of the Landsat program (1970–1981), becoming an international expert in Landsat data products.Her participation in this program expanded upon the works of other NASA scientists in the pursuit of being able to visualize Earth from space. In 1974, Thomas headed a team of approximately 50 people for the Large Area Crop Inventory Experiment (LACIE), a joint effort with NASA’s Johnson Space Center, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. An unprecedented scientific project, LACIE demonstrated the feasibility of using space technology to automate the process of predicting wheat yield on a worldwide basis. In 1976, she attended an exhibition that included an illusion of a light bulb that was lit, even though it had been removed from its socket. The illusion, which involved another light bulb and concave mirrors, inspired Thomas. Curious about how light and concave mirrors could be used in her work at NASA, she began her research in 1977. This involved creating an experiment in which she observed how the position of a concave mirror would affect the real object that is reflected. Using this technology, she would invent the illusion transmitter. On October 21, 1980, she obtained the patent for the illusion transmitter, a device that NASA continues to use today. As a woman and an African American, Thomas worked her way up to associate chief of the Space Science Data Operations Office at NASA.In 1985, she was the NSSDC Computer Facility manager responsible for a major consolidation and reconfiguration of two previously independent computer facilities and infused them with new technology. She then served as the Space Physics Analysis Network (SPAN) project manager from 1986 to 1990 during a period when SPAN underwent a major reconfiguration and grew from a scientific network with about 100 computer nodes to one directly connecting about 2,700 computer nodes worldwide.In 1990, SPAN became a major part of NASA’s science networking and today’s Internet. She also participated in projects related to Halley’s Comet, ozone research, satellite technology and the Voyager spacecraft.At the end of August 1995, she retired from NASA and her positions of associate chief of NASA’s Space Science Data Operations Office, manager of the NASA Automated Systems Incident Response Capability, and as chair of the Space Science Data Operations Office Education Committee.After retiring, Thomas served as an associate at the UMBC Center for Multicore Hybrid Productivity Research. She continued to mentor youth through the Science Mathematics Aerospace Research and Technology, Inc. and the National Technical Association. Thomas’s invention was depicted in a children’s fictional book, television, and video games.Because of her unique career and commitment to giving something back to the community, Thomas had often spoken to groups of students from elementary school through college-/university-age and adult groups. As an role model for potential young black engineers and scientists, she made hundreds of visits to schools and national meetings over the years.She has mentored many students working in the summers at Goddard Space Flight Center and judged at science fairs, working with organizations such as the National Technical Association (NTA) and Women in Science and Engineering (WISE). These latter programs encourage minority and female students to pursue science and technology careers.Throughout her career, Thomas held high-level positions at NASA including heading the Large Area Crop Inventory Experiment (LACIE) collaboration between NASA, NOAA, and USDA in 1974, serving as assistant program manager for Landsat/Nimbus (1975–1976), managing the NSSDC Computer Facility (1985), managing the Space Physics Analysis Network project (1986–1990), and serving as associate chief of the Space Science Data Operations Office. She authored many scientific papers and holds a patent for the illusion transmitter. For her achievements, Thomas has received numerous awards including the Goddard Space Flight Center Award of Merit and NASA’s Equal Opportunity Medal. She mentored countless students Mathematics Aerospace Research and Technology Inc program.In February of 2020, American musician Chance the Rapper posted about Valerie Thomas on his Twitter account, referencing her development of the illusion transmitter and attaching a photograph of Thomas, stating: “This is the NASA physicist who invented 3D Movies and Television. Her name is Valerie Thomas” Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

Month: October 2021

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event was a violent on-field assault against African-American player Johnny Bright by a white opposing player during an American college football game held on October 20, 1951, in Stillwater, Oklahoma.

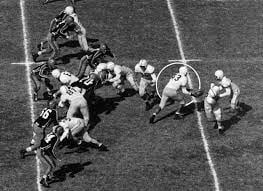

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event was a violent on-field assault against African-American player Johnny Bright by a white opposing player during an American college football game held on October 20, 1951, in Stillwater, Oklahoma. The game was significant in itself as it marked the first time that an African-American athlete with a national profile and of critical importance to the success of his team, the Drake Bulldogs, had played against Oklahoma A&M College (now Oklahoma State University) at Oklahoma A&M’s Lewis Field. Bright’s injury also highlighted the racial tensions of the times and assumed notoriety when it was captured in what was later to become both a widely disseminated and eventually Pulitzer Prize-winning photo sequence.Today in our History – October 20, 1951 – The Johnny Bright incident Johnny Bright’s participation as a halfback/quarterback in the collegiate football game between the Drake Bulldogs and Oklahoma A&M Aggies on October 20, 1951, at Lewis Field was controversial even before it began. Bright had been the first African-American football player to play at Lewis Field two years prior (without incident). In 1951, Bright was a pre-season Heisman Trophy candidate and led the nation in total offense. Bright had never played for a losing team in his college career. Coming into the contest, Drake carried a five-game winning streak, owing much to Bright’s rushing and passing abilities.It was an open secret that Oklahoma A&M players were targeting Bright. Both Oklahoma A&M’s student newspaper, The Daily O’Collegian, and the local newspaper, The News Press, reported that Bright was a marked man, and several A&M students were openly claiming that Bright “would not be around at the end of the game”. Although Oklahoma A&M had integrated in 1949, the Jim Crow spirit was still very much alive on campus.During the first seven minutes of the game, Bright was knocked unconscious three times by blows from Oklahoma A&M defensive tackle Wilbanks Smith. While Smith’s final elbow blow broke Bright’s jaw, he was still able to complete a 61-yard touchdown pass to Drake halfback Jim Pilkington a few plays later. Soon afterward, the injury forced him to leave the game. Bright finished the game with less than 100 yards, the first time in his three-year collegiate career. Oklahoma A&M eventually won 27–14.Bob Spiegel, a reporter with the Des Moines Register, interviewed several spectators after the game, eventually publishing a report on the incident in the October 30, 1951, issue of the newspaper. According to Spiegel’s report, several of the Oklahoma A&M students he interviewed overheard an Oklahoma A&M coach repeatedly say “Get that nigger” whenever the A&M practice squad ran Drake plays against the Oklahoma A&M starting defense prior to the October 20 game. Spiegel also recounted the experiences of a businessman and his wife, who were seated behind a group of Oklahoma A&M practice squad players.At the beginning of the game, one of the players turned around said, “We’re gonna get that nigger.” After the first blow to Bright was delivered by Smith, the same player again turned around and told the businessman, “See that knot on my jaw? That same guy [Smith] gave me that the very same way in practice.”A six photograph sequence of the incident captured by Des Moines Register cameramen John Robinson and Don Ultang clearly showed Smith’s jaw-breaking blow was thrown well after Bright had handed the ball off to Drake fullback Gene Macomber, and was well behind the play. Robinson and Ultang had set up a camera focusing on Bright before the game after the rumors of him being targeted became too loud to ignore. They rushed the film to Des Moines as soon as Bright was knocked out of the game. Ultang said years later that they were very lucky that the incident took place when it did; they had only planned to stay through the first quarter so they could have enough time to develop the pictures before the deadline. The sequence won Robinson and Ultang the 1952 Pulitzer Prize for Photography, and eventually made it into the November 5, 1951, issue of Life.Oklahoma A&M’s president, Oliver Willham, denied anything happened even after evidence of the incident was published nationwide. This began a cover-up that would last over half a century; during that time, whenever the story was discussed, the standard response from A&M/OSU was “no comment”. The determination to gloss over the affair was so strong that when Robert B. Kamm succeeded Willham in 1966, he knew that he could not even discuss the matter even though he had been Drake’s dean of men at the time of the incident.When it became apparent that neither Oklahoma A&M nor the Missouri Valley Conference, to which both Drake and Oklahoma A&M belonged, would take any disciplinary action against Smith, Drake withdrew from the MVC in protest. The Bulldogs would not return to the MVC until 1956 for non-football sports, and would not return for football until 1971. Fellow member Bradley University pulled out of the league in solidarity with Drake and did not return for non-football sports until 1955; its football team never played another down in the MVC (Bradley dropped football in 1970). The incident eventually provoked changes in NCAA football rules regarding illegal blocking, and mandated the use of more protective helmets with face guards.Bright’s broken jaw limited his effectiveness for the remainder of his senior season at Drake, but he earned 70 percent of the yards Drake gained and scored 70 percent of the Bulldogs’ points, despite missing the better part of the final three games of the season. Bright finished fifth in the balloting for the 1951 Heisman Trophy, and played in the post-season East–West Shrine Game and the Hula Bowl.Following his 1952 graduation from Drake, Bright went on to enjoy a 12-year professional football career in the Canadian Football League, retiring in 1964 as the CFL’s all-time leading rusher, and was inducted into the Canadian Football Hall of Fame in 1970.Recalling the incident without apparent bitterness in a 1980 Des Moines Register interview three years before his death, Bright commented: “There’s no way it couldn’t have been racially motivated.” Bright went on to add: “What I like about the whole deal now, and what I’m smug enough to say, is that getting a broken jaw has somehow made college athletics better. It made the NCAA take a hard look and clean up some things that were bad.”When asked about Smith, whom he had not seen since the incident, Bright said he felt “null and void” about Smith, but added: “The thing has been a great influence on my life. My total philosophy of life now is that, whatever a person’s bias and limitation, they deserve respect. Everyone’s entitled to their own beliefs.”Wilbanks Smith received over 1,000 letters regarding the incident. Most of the mail was hate mail or death threats, but some was congratulatory and thankful. Smith maintained that he was not racist, the hit was “not a racial incident,” and that he had landed “the same hit” on a white player earlier in the game. He never apologized for the incident, but said in 2012 that he was glad the incident had helped to integrate college football, saying “It took me a long time before I could smile about it. But now I can. I think it was a tool [Civil Rights’] organizations used, and it was very effective.” Smith died on January 14, 2020 at the age of 89.On September 28, 2005, Oklahoma State University President David J. Schmidly wrote a letter to Drake President David Maxwell formally apologizing for the incident. The apology came 22 years after Bright’s death. Schmidly, reiterating a conversation earlier in the month over the phone, called the team’s behavior that day “an ugly mark on Oklahoma State University and college football”. Research more about this great American tragedy and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – LIF – Today’s American Champion is an American anthropologist, educator, museum director, and college president.

GM – LIF – Today’s American Champion is an American anthropologist, educator, museum director, and college president. Cole was the first female African-American president of Spelman College, a historically black college, serving from 1987 to 1997. She was president of Bennett College from 2002 to 2007. During 2009–2017 she was Director of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African Art.Today in our History – October 19, 1936 – Johnnetta Betsch Cole was born 1936.Johnnetta Betsch was born in Jacksonville, Florida, on October 19, 1936. Her family belonged to the African-American upper class; She was a granddaughter of Abraham Lincoln Lewis, Florida’s first black millionaire, entrepreneur and cofounder of the Afro-American Industrial and Benefit Association, and Mary Kingsley Sammis.Sammis’ great-grandparents were Zephaniah Kingsley, a slave trader and slave owner, and his wife and former slave Anna Madgigine Jai, a Wolof princess who was originally from present-day Senegal. Her Fort George Island home is protected as Kingsley Plantation, a National Historic Landmark.Cole enrolled at the age of 15 in Fisk University, a historically black college. She transferred to Oberlin College in Ohio, where she completed a Bachelor of Arts degree in sociology in 1957. She attended graduate school at Northwestern University, earning her Master of Arts (1959) and Doctor of Philosophy (1967) degrees in anthropology.She did her dissertation field research in Liberia, West Africa, in 1960–1961 through Northwestern University as part of their economic survey of the country.Cole served as a professor at Washington State University from 1962 to 1970, where she cofounded one of the US’s first black studies programs. In 1970 Cole began working in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where she served until 1982.While at the University of Massachusetts, she played a pivotal role in the development of the university’s W.E.B. Du Bois Department of African-American Studies. Cole then moved to Hunter College in 1982, and became director of the Latin American and Caribbean Studies program. From 1998 to 2001 Cole was a professor of Anthropology, Women’s Studies, and African American Studies at Emory University in Atlanta.In 1987, Cole was selected as the first black female president of Spelman College, a prestigious historically black college for women. She served until 1997, building up their endowment through a $113 million capital campaign, attracting significantly higher enrollment as students increased, and, overall, the ranking of the school among the best liberal arts schools went up. Bill and Camille Cosby contributed $20 million to the capital campaign.After teaching at Emory University, she was recruited as president of Bennett College for Women, also a historically black college for women. There she led another successful capital campaign. In addition, she founded an art gallery to contribute to the college’s culture. Cole is currently the Chair of the Johnnetta B. Cole Global Diversity & Inclusion Institute founded at Bennett College for Women. She is a member of Delta Sigma Theta sorority.She was Director of the National Museum of African Art, part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, during 2009–2017. During her directorship the controversial exhibit, “Conversations: African and African-American Artworks in Dialogue,” featuring dozens of pieces from Bill and Camille Cosby’s private art collection was held in 2015, coinciding with accusations of sexual assault against the comedian.Cole has also served in major corporations and foundations. Cole served for many years as board member at the prestigious Rockefeller Foundation. She has been a director of Merck & Co. since 1994. From 2004 to2006, Cole was the Chair of the Board of Trustees of United Way of America and is on the Board of Directors of the United Way of Greater Greensboro.Since 2013, Cole has been listed on the Advisory Council of the National Center for Science Education.President-elect Bill Clinton appointed Cole to his transition team for education, labor, the arts, and humanities in 1992. He also considered her for the cabinet post of Secretary of Education. However, when The Jewish Daily Forward reported that she had been a member of the national committee of the Venceremos Brigades, which the Federal Bureau of Investigation had tied to Cuban intelligence forces, Clinton did not advance her nomination.· In 2018 she was awarded the Legend in Leadership Award for Higher Education from the Yale Chief Executive Leadership Institute· American Alliance of Museums Honors Dr. Johnnetta Cole with 2017 Award for Distinguished Service to Museums· In 2013, Cole received the highest citation of the International Civil Rights Center & Museum, the Alston-Jones International Civil and Human Rights Award.· Cole has received more than 40 honorary degrees, including those from Williams College and Bates College in 1989, Oberlin College in 1995, Mount Holyoke College in 1998, Mills College in 1999, Howard University and North Carolina A&T State University in 2009, and Gettysburg College in 2017.·She received honorary membership in Phi Beta Kappa from Yale in 1996, and has served as a Phi Beta Kappa Senator.· In 1995, Cole received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement presented by Awards Council member and Morehouse College President Walter E. Massey.· She received a Candace Award from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women in 1988. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American musician, composer, and Christian evangelist influential in the development of early blues and 20th-century gospel music.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American musician, composer, and Christian evangelist influential in the development of early blues and 20th-century gospel music.He penned 3,000 songs, a third of them gospel, including “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” and “Peace in the Valley”. Recordings of these sold millions of copies in both gospel and secular markets in the 20th century. Born in rural Georgia, Dorsey grew up in a religious family but gained most of his musical experience playing blues at barrelhouses and parties in Atlanta. He moved to Chicago and became a proficient composer and arranger of jazz and vaudeville just as blues was becoming popular. He gained fame accompanying blues belter Ma Rainey on tour and, billed as “Georgia Tom”, joined with guitarist Tampa Red in a successful recording career.After a spiritual awakening, Dorsey began concentrating on writing and arranging religious music. Aside from the lyrics, he saw no real distinction between blues and church music, and viewed songs as a supplement to spoken word preaching. Dorsey served as the music director at Chicago’s Pilgrim Baptist Church for 50 years, introducing musical improvisation and encouraging personal elements of participation such as clapping, stomping, and shouting in churches when these were widely condemned as unrefined and common. In 1932, he co-founded the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses, an organization dedicated to training musicians and singers from all over the U.S. that remains active.The first generation of gospel singers in the 20th century worked or trained with Dorsey: Sallie Martin, Mahalia Jackson, Roberta Martin, and James Cleveland, among others.Author Anthony Heilbut summarized Dorsey’s influence by saying he “combined the good news of gospel with the bad news of blues”. Called the “Father of Gospel Music” and often credited with creating it, Dorsey more accurately spawned a movement that popularized gospel blues throughout African American churches in the United States, which in turn influenced American music and helped spawned the creation of all major American music forms in the 1900s and 2000s. Today in our History – October 17, 1933 – Thomas Andrew Dorsey (July 1, 1899 – January 23, 1993) directed the Pilgrim Baptist Church choir performance at the 1933 World’s Fair.Gospel historian Horace Boyer writes that gospel music “has no more imposing figure” than Dorsey, and the Cambridge Companion to Blues and Gospel Music states that he “defined” the genre. Folklorist Alan Lomax claims that Dorsey “literally invented gospel”. In Living Blues, Jim O’Neal compares Dorsey in gospel to W. C. Handy, who was the first and most influential blues composer, “with the notable difference that Dorsey developed his tradition from within, rather than ‘discovering’ it from an outsider’s vantage point”. Although he was not the first to join elements of the blues to religious music, he earned the honorific “Father of Gospel Music”, according to gospel singer and historian Bernice Johnson Reagon, for his “aggressive campaign for its use as worship songs in black Protestant churches”.Throughout his career, Dorsey composed more than 1,000 gospel and 2,000 blues songs, an achievement Mahalia Jackson considered equal to Irving Berlin’s body of work. The manager of a gospel quartet active in the 1930s stated that songs written by Dorsey and other songwriters copying him spread so far in such a short time that they were called “dorseys”. Horace Boyer attributes this popularity to “simple but beautiful melodies”, unimposing harmonies, and room for improvisation within the music. Lyrically, according to Boyer, Dorsey was “skilled at writing songs that not only captured the hopes, fears, and aspirations of the poor and disenfranchised African Americans but also spoke to all people”. Anthony Heilbut further explains that “the gospel of [Charles] Tindley and Dorsey talks directly to the poor. In so many words, it’s about rising above poverty while still living humble deserting the ways of the world while retaining its best tunes.” Aside from his prodigious songwriting, Dorsey’s influence in the gospel blues movement brought about change both for individuals in the black community and communities as a whole. He introduced rituals and standards among gospel choirs that are still in use. At the beginning of worship services, Dorsey instructed choruses to march from the rear of the sanctuary to the choir-loft in a specific way, singing all the while. Choir members were encouraged to be physically active while singing, rocking and swaying with the music.He insisted that songs be memorized rather than chorus members reading music or lyrics while performing. This freed the choir members’ hands to clap, and he knew anyway that most of the chorus singers in the early 1930s were unable to read music. Moreover, Dorsey refused to provide musical notation, or use it while directing, because he felt the music was only to be used as a guide, not strictly followed. Including all the embellishments in gospel blues would make the notation prohibitively complicated. Dorsey instead asked his singers to rely on feeling. I think about all these blue-collar people who had to deal with Jim Crow, meager salaries, and yet the maid who cleaned up somebody else’s house all week long, the porter, the chauffeur, the gardener, the cook, were nobody. They had to sit in the back of the bus, they were denied their rights, but when they walked into their church on Sunday morning and put on a robe and went down that aisle and stood on that choir stand, the maid became a coloratura, and when she stood before her church of five hundred to a thousand, two thousand people, she knew she was somebody. And I think the choir meant so much to those people because for a few hours on Sunday, they were royalty.– Gospel singer Donald VailsWhile presiding over rehearsals, Dorsey was strict and businesslike. He demanded that members attend practice regularly and that they should live their lives by the same standards promoted in their songs. For women, that included not wearing make-up.Choruses were stocked primarily with women, often untrained singers with whom Dorsey worked personally, encouraging many women who had little to no participation in church before to become active. Similarly, the NCGCC in 1933 is described by Dorsey biographer Michael W. Harris as “a women’s movement” as nine of the thirteen presiding officer positions were held by women. Due to Dorsey’s influence, the definition of gospel music shifted away from sacred song compositions to religious music that causes a physical release of pain and suffering, particularly in black churches. He infused joy and optimism in his written music as he directed his choirs to do perform with uplifting fervor as they sang.The cathartic nature of gospel music became integral to the black experience in the Great Migration, when hundreds of thousands of black Southerners moved to Northern cities like Detroit, Washington, D.C., and especially Chicago between 1919 and 1970. These migrants were refugees from poverty and the systemic racism endemic throughout the Jim Crow South. They created enclaves within neighborhoods through church choirs, which doubled as social clubs, offering a sense of purpose and belonging. Encountering a “golden age” between 1940 and 1960, gospel music introduced recordings and radio broadcasts featuring singers who had all been trained by Dorsey or one of his protégées. As Dorsey is remembered as the father of gospel music, other honorifics came from his choirs: Sallie Martin, considered the mother of gospel (although Willie Mae Ford Smith, also a Dorsey associate, has also been called this), Mahalia Jackson, the queen of gospel, and James Cleveland, often named the king of gospel.In 1936, members of Dorsey’s junior choir became the Roberta Martin Singers, a successful recording group which set the standard for gospel ensembles, both for groups and individual voice roles within vocal groups. In Dorsey’s wake, R&B artists Dinah Washington, who was a member of the Sallie Martin Singers, Sam Cooke, originally in the gospel band the Soul Stirrers, Ray Charles, Little Richard, James Brown, and the Coasters recorded both R&B and gospel songs, moving effortlessly between the two, as Dorsey did, and bringing elements of gospel to mainstream audiences. Despite racial segregation in churches and the music industry, Dorsey’s music had widespread crossover appeal. Prominent hymnal publishers began including his compositions in the late 1930s, ensuring his music would be sung in white churches. His song “Peace in the Valley”, written in 1937 originally for Mahalia Jackson, was recorded by, among others, Red Foley in 1951, and Elvis Presley in 1957, selling more than a million copies each. Foley’s version has been entered into the National Recording Registry as a culturally significant recording worthy of preservation.Notably, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” was the favorite song of Martin Luther King Jr., who asked Dorsey to play it for him on the eve of his assassination. Mahalia Jackson sang at his funeral when King did not get to hear it. Anthony Heilbut writes that “the few days following his death, ‘Precious Lord’ seemed the truest song in America, the last poignant cry of nonviolence before a night of storm that shows no sign of ending”. Four years later, Aretha Franklin sang it at Jackson’s funeral. Since its debut it has been translated into 50 languages. Chicago held its first gospel music festival as a tribute to Dorsey in 1985; it has taken place each year since then. Though he never returned to his hometown, efforts to honor Dorsey in Villa Rica, Georgia, began a week after his death. Mount Prospect Baptist Church, where his father preached and Dorsey learned music at his mother’s organ, was declared a historic site by the city, and a historical marker was placed at the location where his family’s house once stood. The Thomas A. Dorsey Birthplace and Gospel Heritage Festival, established in 1994, remains active. As of 2020, the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses has 50 chapters around the world. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African American who escaped enslavement to become an abolitionist, newspaper editor, labor leader, and Congregational minister.

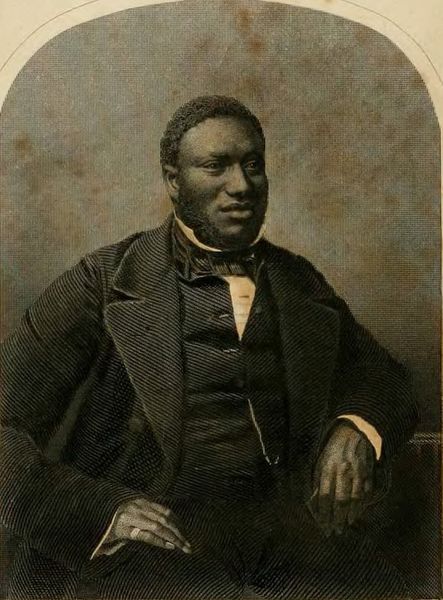

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African American who escaped enslavement to become an abolitionist, newspaper editor, labor leader, and Congregational minister.He was author of the influential book: Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro: his anti-slavery labours in the United States, Canada and England, written after his speeches throughout Britain in 1853. It enabled him to raise funds for the Anti-slavery Society of Canada, where many escaped slaves from the USA were arriving in the 1850s.Today in our History – October 17, 1817 – Samuel Ringgold Ward (October 17, 1817 – c. 1866) was born.Samuel Ringgold Ward was born into slavery in 1817 on Maryland’s eastern shore but fled as a child with his parents in 1820 to New Jersey and soon relocated to New York in 1826. Once settled, Ward’s parents enrolled him in at the African Free School.His beliefs in the end of slavery and his oratory skills led him to politics where he joined first the Liberty Party in 1840, where he remained until 1848, and later the Free Soil Party in 1848, becoming one of the few from the latter party that was interested in the abolitionist aspect of preventing further inclusion of slave states into the union.Indeed, at the Liberty Party National Convention in June 1848, Samuel R. Ward received 12 of a possible 84 votes to place second in balloting for that party’s nomination as their candidate for the Office of U.S. Vice President.Other abolitionists both white and black were well aware of Ward’s oratory abilities and commended his brilliant efforts in the abolitionist movement. His activities brought him in close contact with fellow orator and abolitionist Frederick Douglass who said of him, “As an orator and thinker [Ward] was vastly superior to any of us” and that “the splendors of his intellect went directly to the glory of race.”Little progress had been made in America whilst he had been away and he was to record that here I saw more of the foolishness, wickedness, and at the same time the invincibility, of American Negro-hate, than I ever saw elsewhere. Whilst there, his youngest son, William Reynolds Ward, died and was buried; and two of his daughters, Emily and Alice, were born. From Cortland the family moved to Syracuse, New York, in 1851. However the stay was brief, on account of Samuel Ward participating in the “Jerry Rescue” on the first day of October in that year, leading him to emigrate in some haste to Canada, that November.During the last few years of Samuel Ward’s residence in the United States he had become editor and part owner of two newspapers; the Farmer and Northern Star, and Boston’s Impartial Citizen. He was a firm believer in the need for anti-slavery labors, organizations, agitation, and newspapers and conscious of the need to keep the papers from being censured, or worse as in the death of Elijah P. Lovejoy, he commenced the study of law.Freed blacks during the Antebellum also faced discrimination in employment, as black laborers were not welcome in most unions. In response, Frederick Douglass and Ward helped organize the American League of Colored Laborers, the first black American labor union.Assembled on June 13, 1850 in the lecture room of Zion’s church in New York City, the League appointed Samuel Ringgold Ward as its first president, Frederick Douglass as its vice-president, and Henry Bibb as its secretary. Although short-lived and stymied by the small number of black workers in cities at the time, the union’s goals included the creation of a fund to give loans to black entrepreneurs, the creation of a bank that would provide credit and encourage saving, and an industrial fair. In Canada, he worked with Mary Ann Shadd Cary to found a newspaper, The Provincial Freeman, in 1853. While she was the editor-in-chief, as the first woman publisher in North America, she was afraid of not being taken seriously and originally hid her involvement with the paper by putting Ward’s and the Rev. Alexander McArthur’s names on the masthead. “Proclaimed editor of this bold venture, Ward only lent his name to the newspaper to generate interest and subscriptions.” He was then offered work by the Anti-slavery Society of Canada, who decided he should visit Britain to further their anti-slavery work. He was given the names of contacts in London who would be keen to accommodate his visit, to strengthen their own long-standing anti-slavery work, and might be willing to help organise fund-raising for anti-slavery work in Canada.Ward’s preparation paid off and he was well received in Britain early in 1853; as Samuel Ward records,The Rev. Thomas Binney, to whom I brought letters from Rev. Mr. Roaf, my pastor, received me most kindly. Mrs. Binney acted as if we had been acquainted for the preceding six-and-twenty years; and, being the first London lady with whom I had the pleasure of acquaintance, I saw in her what I have since seen in English people of all ranks, who are really genteel – a most skilful and yet an indescribably easy way of making one feel perfectly at case with them. I cannot tell how it is done.At the annual meeting of the Congregational Union, Samuel Ward was formally introduced to the body by the Secretary, Rev. George Smith of Trinity Independent Chapel, in company with Rev. Charles Beecher, the brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, whom he had not met before. A dinner for the Congregational ministers and delegates was organised at Radley’s Hotel, at which Samuel Ward gave his first London anti-slavery speech about the need for financial support in Canada:The amiable Rev. James Sherman, at that time minister of Surrey Chapel, with his accustomed kindness took me in his carriage to the dinner; and afterwards, for four months, not only made me his guest, but made his house my home. I never lived so long with any other person, on the same terms. While I live, that dear gentleman will seem to me as a most generous fatherly friend.Samuel Ward’s visit to London was, he considered, at a most fortunate time for his fund-raising endeavour, because: “of the twofold fact that Uncle Tom’s Cabin was in every body’s hands and heart, and its gifted authoress was the English people’s guest. For anti-slavery purposes, a more favourable time could not have been chosen for visiting England.” As he further explained, “When Mrs. Stowe arrived in England… the book from the one side of the Atlantic, the address (by James Sherman) from the other side… awakened more attention to the anti-slavery cause in England, in 1853, than had existed since the agitation of the emancipation question in 1832.” Ward, having met Mrs. Stowe at the house of Rev. James Sherman, next door to his Surrey Chapel on Blackfriars Road, in May 1853, was invited to stay at the Surrey Chapel Parsonage along with Mrs Stowe’s husband, the Rev. Dr. Calvin Stowe, and her brother Rev. Charles Beecher, for three weeks.On 7 June 1853 Samuel Ward was able to deliver his major London anti-slavery speech, and had secured ‘Lord’ Shaftesbury to take the chair. Ward’s address had a successful impact, for almost immediately—21 June—it led to the formation of a London Committee to seek financial support for the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada. The Committee comprised ‘Lord’ Shaftesbury, Rev. J. Sherman, and S. H. Horman-Fisher, with G. W. Alexander its treasurer. This led to several months of hectic speaking engagements for Samuel Ward. He received invitations to speak at the London Missionary Society, kindred charities, and the pulpits of the most distinguished Dissenting divines in the land. Travelling in these causes took him to almost every county in England, and then on to Scotland. After just ten months, some £1,200 had been donated and it was possible to bring the organising committee to a close. A final, large meeting was held at Crosby Hall on the 20th of March, 1854, chaired by Samuel Gurney, where Samuel Ward was accompanied by many of those who had helped him—Rev. James Sherman, Samuel Horman Horman-Fisher, L. A. Chamerovzow, Esq., Rev. James Hamilton D.D., Rev. John Macfarlane, and Josiah Conder.Samuel Ward’s success enabled the Anti-slavery society of Canada to finance its work in support of escaped slaves from the USA, and in the following year, 1855 Ward published his influential book recounting all that he had achieved. The proceeds enabled him to retire to Jamaica.Samuel Ringgold Ward died in 1866 after spending his last 11 years of life as a minister and farmer in Jamaica. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event took place when most American’s were afraid that something tragic was going to happen.

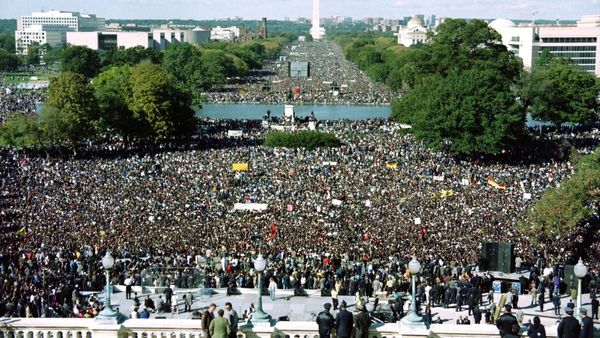

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event took place when most American’s were afraid that something tragic was going to happen. I was proud to be a part of it by being there and having the opportunity to speak the night before to a select group of high school students that were our talented tenth for 1995. Snipers were in the trees, roof tops and naturally in the masses but no one was even charged with anything a great afternoon in Washington, D.C. Today in our History – October 16, 1995 – The Million Man March in Washington, D.C.On October 16, 1995, an estimated 850,000 African American men from across the United States gathered together at the National Mall in Washington, D.C. to rally in one of largest demonstrations in Washington history. This march surpassed the 250,000 who gathered in 1963 for the March on Washington where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his historic “I Have a Dream” speech. This assembly of black men was organized and hosted by the Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan who called for all able-bodied African American men to come to the nation’s capital to address the ills of black communities and call for unity and revitalization of African American communities. Although the Million Man March was proposed and organized primarily by the leader of Islam, many religions, institutions, and community organizations across the spectrum of African America joined together not only for a rally of black men but also to build what many saw as a movement directed toward a future renaissance of the black race.Those unable to attend the march in Washington were asked by Louis Farrakhan to stay home from work and keep their children at home from school in a show of solidarity and support for the objectives of the march. Farrakhan also called on march participants and supporters to refrain from spending money on October 16 to illustrate to the United States the importance of African American dollars to the national economy.Besides the keynote address by Minister Louis Farrakhan, several prominent speakers addressed those gathered at the Washington Mall including civil rights activists Benjamin Chavis, Jesse Jackson, Rosa Parks, and Dick Gregory. Stevie Wonder entertained the gathering with his songs while Maya Angelou used her poetry to offer advice to the men at the rally. The message of most of the speeches called for black men to “bring the spirit of God back into your lives.” These marchers were also encouraged to register to vote to build black political power.March participants took a public pledge to support their families, refrain from violence and physical or verbal abuse toward women and children, and renounce violence against other men “except in self-defense.” They also pledged abstinence from drugs or alcohol and to concentrate their efforts on building black businesses and social and cultural institutions in the communities where they lived. The march participants were then asked to “go back home” to implement the changes they had pledged.Although many of the changes pledged in Washington on October 16 to revitalize African American communities were not prominently in evidence in the years that followed the march, organizers claimed two notable successes. In the year after October 16, over 1.5 million black men registered to vote for the first time. There was also an upsurge in the number of black children adopted by African American families. Research more about this great American Champion event and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American orator, activist, suffragist, and reformer.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American orator, activist, suffragist, and reformer. Called “the best known Colored Woman in the United States,” She was among the most prominent African Americans of her time. In 2005, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.Today in our History – October 15, 1923 – Mary Burnett Talbert (September 17, 1866 – October 15, 1923) died.Mary Morris Burnett Talbert was born in Oberlin, Ohio in 1866. As the only African-American woman in her graduating class from Oberlin College in 1886, Burnett received a Bachelor of Arts degree, then called an S.P. degree. She entered the field of education, first as a teacher in 1886 at Bethel University in Little Rock. She then became assistant principal of the Union High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1887, the highest position held by an African-American woman in the state. In 1891, she married William H. Talbert, moved to Buffalo, New York, and joined Buffalo’s historic Michigan Avenue Baptist Church.Talbert earned a higher education degree at a time when a college education was controversial for European-American women and extremely rare for African-American women. When women’s organizations were segregated by race, Talbert was an early advocate of women of all colors working together to advance their cause, and reminded white feminists of their obligations towards their less privileged sisters of color.Described by her peers as “the best-known colored woman in the United States,” Talbert used her education and prodigious energies to improve the status of Black people at home and abroad. In addition to her anti-lynching and anti-racism work, Talbert supported women’s suffrage. In 1915 she spoke at the “Votes for Women: A Symposium by Leading Thinkers of Colored Women” in Washington, D.C. During her national and international lecture tours, Talbert educated audiences about oppressive conditions in African-American communities and the need for legislation to address these conditions. She was instrumental in gaining a voice for African-American women in international women’s organizations of her time.As a founder of the Niagara Movement, Talbert helped to launch organized civil rights activism in America. The Niagara Movement was radical enough in its brief life to both spawn and absorb controversy within the Black community, preparing the way for its successor, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).Central to the efforts of both organizations, Mary Talbert helped set the stage for the civil rights gains of the 1950s and 1960s. Talbert’s long leadership of women’s clubs helped to develop black female organizations and leaders in communities around New York and the United States. Women’s clubs provided a forum for African-American women’s voices at a time when they had restricted opportunities in public and civic life. In both Black and white communities, women’s clubs fostered female leadership.As a historic preservation pioneer, Talbert saved the Frederick Douglass home in Anacostia, D.C. after other efforts had failed. Buffalo’s 150-year-old Michigan Avenue Baptist Church, to which the Talbert family belonged, has been named to the United States National Register of Historic Places. Many prominent African Americans worshipped or spoke there. The church also had a landmark role in abolitionist activities. In 1998, a marker honoring Talbert, who served as the church’s treasurer, was installed in front of the Church by the New York State Governor’s Commission Honoring the Achievements of Women.In October 2005, Talbert was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York. She is also remembered around the United States as the namesake of clubs and buildings.Talbert died on October 15, 1923, and is buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery (Buffalo). A small collection of Talbert family papers, concerned mostly with property and estate matters, survives in the Research Library of the Buffalo History Museum. The period in United States history commonly referred to as the Progressive Era spanned from 1890–1920. It represented a progressive shift in what Axinn and Stern (2005) refer to as “the lines between the countryside and the city, between workers and the middle class, between foreigners and native-born, and between men and women” (Axinn & Stern, 2005, p. 127). Not mentioned in this shift is the gruesome treatment of African-Americans under the Southern “Jim Crow” laws which excluded Blacks from political, economic, public, and educational spheres of influence.These measures represented a tightening of oppressive politics and an era of social subservience, which arguably lasts into the present time. Discriminatory efforts took shape in black segregation in white social settings and strategically limiting blacks’ right to vote with a combination of the grandfather clause, poll taxes, and violent efforts at voting sites (Woloch & Johnson, 2009). Progressive era political reform was seen as necessary, but changing the attitudes and actions toward Blacks in the South was not on this political agenda.The hostile environment of the South combined with the loss of jobs and the threat of lynching encouraged the migration of many Blacks to the north. It is estimated that from 1890 to 1910, roughly 200,000 African Americans left the South and this number continued to increase during World War I (Woloch & Johnson, 2009). The move north represented employment opportunities in the textile industry, in large factories, automobile production, and the famed meat packing industry of New York, but we’re still not free from the harassment and discrimination that characterized this period of being Black in America. Axinn and Stern (2005) surmise that “the Black population was generally unaffected by reform activities and the social welfare benefits that resulted from them. In an era marked by economic progress and social mobility, the group remained poor and powerless” .Despite the bleak picture painted by Axinn and Stern, African-American leadership was not at a shortage, and “powerless” certainly does not describe the Black pioneers of this era. Notable Black change agents including Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells, and Mary McLeod Bethune helped lead the fight for Black equality and opportunity. Similarly influential but less well-noted activists include Mary Church Terrell, Nannie Helen Burroughs, and Mary Morris Burnett Talbert, who is a noted international activist, educator, leader, and social reformer. In a 1916 speech, Talbert states, “no Negro woman can afford to be an indifferent spectator of the social, moral, religious, economic, and uplift problems that are agitated around [her]” (Williams, 1994). Her life’s work embodies these principles of dedication and hard work to improve the plight of Blacks and all people during this era.Hallie Quinn Brown, having the opportunity to befriend Mary Talbert, details a personal side of this phenomenal woman stating, “Mrs. Talbert possessed a kind, thoughtful, generous nature. She did not hesitate to do the smallest deed to the humblest person in any possible way. For if one does not possess these qualities in the small things in life she can never fully expand to the greater ones. Her personality was most charming, her smile an object of beauty. She possessed a ready and versatile tongue and pen. A letter from her was almost equal to a face-to-face conversation. She was at once graceful and gracious. By her ability, her oratory, and her pleasing personality, she held the undivided attention of an audience…”Capturing the attention of an audience was not limited to Talbert’s speaking engagements; some of her most formidable actions came in the form of letters detailing the strategy and philosophy behind movements such as the anti-lynching crusade. In a 1922 letter printed in the Crisis magazine, Talbert outlines the urgency of the National Association of Colored Women’s Club’s commitment to an anti-lynching campaign that did not divide among racial lines. In the opening lines, she asserts: “The hour has come in America for every woman, white and black, to save the name of her beloved country from shame by demanding that the barbarous custom of lynching and burning at the stake be stopped now and forever” (Talbert, 1922).Lobbying the support of white woman’s organizations, Talbert recognized the human element in a lynching that extended beyond race to basic human rights. Her efforts were bold and likely dangerous as she elicited the contributions of Jewish women and Christian women in what she labeled “American womanhood…working for one particular objective…” (Talbert, 1922). She was well respected in the community of female leaders and Mary White Ovington, also influential in the Nation Association for the Advancement of Colored People, expressed to the National Women’s Party that “Mrs. Talbert is able, liberal in thought, and perhaps the best known colored woman in the United States today” (Ovington, 1920).Although Talbert was well received in some organizational circles, there were other venues that despite her recognition and champion for women’s rights, she was still judged by the color of her skin. Mary Jane Brown (2000) highlights Talbert’s official 1920 trip to Europe to attend the International Council of Women in Christiana, Norway as a delegate.In Paris, Talbert was with three other white female delegates and was not allowed into a dining room for breakfast because of her race. In every other country on this tour, she was treated well, but not allowed to a tea sponsored by the YWCA in Paris (Brown, 2000, p. 39).This slice of history raises numerous questions regarding the status of gender and race not only in the United States but in the international community. Talbert was well aware of national and international perceptions of her prominence and the ideological environment that she sought to advance. In a short essay titled “Women and Colored Women,” Mary Talbert offers her opinion of the gender and races dynamic in terms of women’s voting right by stating, “It should not be necessary to struggle forever against popular prejudice, and with us as colored women, this struggle becomes two-fold, first because we are women and second because we are colored women. Although some resistance is experienced in portions of our country against the ballot for women, I firmly believe that enlightened men are now numerous enough everywhere to encourage this just privilege of the ballot for women, ignoring prejudice of all kinds…by her peculiar position the colored woman has gained clear powers of observation and judgment-exactly the sort of powers which are today peculiarly necessary to the building of an ideal country” (Talbert, 1915).Mary Talbert was certainly a powerful woman who reflected a lasting commitment toward improving the social welfare of women and African-Americans. In 1922 her numerous accomplishments were recognized as she became the first black woman to receive the coveted NAACP’s Spingarn Medal, not only for her successful work in anti-lynching campaigns but her leadership in the Phyllis Wheatley Club of Colored Women, charter member status of the Empire Federation of Women’s Clubs and her headship in preserving and restoring the Frederick Douglass Home in Anacostia as previously mentioned (Williams, 1993). Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM –LIF – Today’s American Champion was an American educator, anthropologist, writer, researcher, and scholar who became the first African American to hold a full faculty position at a major white university when he joined the staff of the University of Chicago in 1942, where he served for the balance of his academic life.

GM –LIF – Today’s American Champion was an American educator, anthropologist, writer, researcher, and scholar who became the first African American to hold a full faculty position at a major white university when he joined the staff of the University of Chicago in 1942, where he served for the balance of his academic life. He was considered one of the most promising black scholars of his generation.Among his students during his tenure at the University of Chicago were anthropologists St. Clair Drake and sociologist Nathan Hare. Davis, who has been honored with a commemorative postage stamp by the United States Postal Service, is best remembered for his pioneering anthropology research on southern race and class during the 1930s, his research on intelligence quotient tests in the 1940s and 1950s, and his support of “compensatory education,” an area in which he contributed to the intellectual genesis of the federal Head Start Program.Today in our History – October 14, 1902 – William Boyd Allison Davis (October 14, 1902 – November 21, 1983) was born.Born in 1902 as the first child of John Abraham and Gabrielle Davis, William Boyd Allison Davis, who would later be known as Allison Davis, was raised in a family well-acquainted with both achievement and activism. He had a younger sister, Dorothy, and a younger brother, John Aubrey Davis, Sr. Davis’s grandfather had been an abolitionist lawyer.His father led a group of 17 white clerks as the head of a government printing office before his demotion under the policies of President Woodrow Wilson’s administration and chaired the anti-lynching committee of Washington D.C.’s chapter of the NAACP. Thus, he was a leader in his community, and Davis would describe him as a “brave man” who was “already marked in a town of 236 citizens” as a large landowner who “further angered whites by registering and voting.”This contrasted sharply with the elitism of many upper-class African Americans, whom Davis would citicize throughout his life for their lack of leadership in the struggle for racial equality and attempts to distance themselves from lower-class blacks. He is the father of Allison S. Davis.Davis entered Washington D.C.’s segregated Dunbar High School in 1916 and, like his father before him, graduated as its valedictorian. The school had been founded almost a half-century before, making it the nation’s oldest public black high school, and had since developed a reputation that pulled black families to the nation’s capital for the chief purpose of gaining residency within the school district.Bucking national trends, the school had settled firmly in the Du Bois camp regarding black education and offered a rigorous college preparatory curriculum that included Greek and Latin. Though the quality of black colleges would steadily increase through the mid-century, at the time of Davis’s graduation most were still teaching primary and secondary curricula; the ticket to the white post-graduate program was most often through the white university. Williams College had a singular arrangement with Dunbar that allotted one full merit-based scholarship per year to the valedictorian. From this agreement Williams derived the majority of its black cohort, and in 1920 drew Davis into its ranks by graduating first in his class at Dunbar.Davis excelled at Williams, graduating as valedictorian in 1924 with a degree in English summa cum laude as well as membership in Phi Beta Kappa. During his studies, he gravitated toward the poetry of Robert Frost, whose stoic depiction of working class people resembled his own admiration for their resilience and adaptability. Though Williams offered a racially integrated classroom environment and had a tradition of supporting the early abolitionist movement, Davis and other black students endured segregation in campus housing; during his years there, the few black students were forced to live together to avoid the possible scandal that could accompany housing them with white students, and they were not permitted to attend social events on campus. Nonetheless, the atmosphere at Williams was relatively progressive for its time, and Davis got along well with many of his white peers, among whom were several Southerners. He also became close friends with Sterling Brown, a fellow Dunbar alumnus, who later recalled the instances of prejudice and social isolation he and other black students endured while at Williams in his essay “Oh Didn’t He Ramble.” In spite of an excellent academic performance and amicable relationships with peers and aculty, Davis was rejected for a teaching assistant position upon graduation in 1924 under the pretext that the school had too many Southern students to permit his appointment. With his post-graduation ambitions at Williams frustrated, in 1924 Davis entered Harvard University on a scholarship, where he earned his master’s degree in literature a year later. Among his professors were the well-known literary critics Bliss Perry and George Lyman Kittredge. However, the most influential intellectual tradition that Davis encountered during his year there came from Irving Babbitt and his New Humanism, in which he saw similarities with his own disdain for the materialistic culture of the black upper classes and the lack of moral leadership among blacks on a national level. This criticism recurred in his work in the late 1920s and early thirties when he participated actively in the explosion of black literature and culture known as the New Negro Renaissance.After graduation, the reality of finding a job in academics set in. Few universities would hire an African American teacher, so Davis’s choices were limited. In the Fall of 1925 he began teaching at the Hampton Institute, later Hampton University, one of the many segregated black colleges throughout the South. Davis realized that a cultural barrier separated him from his students, many of whom came from the most acutely segregated regions of the Deep South and lacked the rigorous academic training and privileged upbringing that he had enjoyed. This division, along with the paternalistic attitude of the Institute which manifested in the form of a strictly regimented campus life and an adherence to segregationist policies, frustrated him and eventually would drive him to change his academic focus from the arts to social sciences in a bid to make a greater impact on society. In the meantime, he fought the most egregious injustices at the Institute by helping students who were organizing a petition with a list of demands to the administration. The protest was quashed, but Davis continued to support a small group of promising students who grew to admire his work, among whom was St. Clair Drake, who was to make important contributions to Davis’s research during the 1930s for Deep South and who later became an important anthropologist in his own right.While at Hampton between 1925 and 1931, he remained actively involved in the literature of what was then known as the “New Negro Renaissance.” Likewise, in 1927 he published “In Glorious Company,” a narrative essay which describes a group of working-class blacks during their train ride North. This piece displayed his unique literary voice based on respect for the resilience of ordinary blacks who endured injustices every day, while at the same time it avoided an excessively romanticized depiction of African-American life or a reliance on realism as a way to scandalize the reader. This was a departure from many previous writers of the Renaissance who depicted success in the black struggle as part of an effort to highlight the artistic achievements of their race. Davis’s approach, which David Varel identifies in the tradition of “Negro Stoicism,” combined elements of Babbitt’s New Humanism as well as his own belief that literature should focus on uplifting ordinary blacks. During the same period he regularly corresponded with W.E.B. Du Bois and published several pieces in The Crisis, including the poems “To Those Dead and Gone” and “Gospel for Those Who Must,” always centered on the theme of perseverance in the lives of poor blacks. However, his most notable work during this era was the polarizing 1929 essay “The Negro Deserts His People,” in which he harshly criticized the black bourgeoisie for having abandoned the masses in their struggle for equality; the concern of class stratification continued to guide his work throughout his career, as he transitioned from the arts to social science in the early 30s and sought to directly confront class differences in the black community.By the late 1920s, Davis sought other ways to effect change on a broader scale, and he began to seek funding for an anthropological study of African Americans and their folk culture by studying its African roots, perhaps interested by the emphasis on pan-Africanism that emerged during the Renaissance. He corresponded with Bronisław Malinowski at the London School of Economics and Dietrich Westermann of the University of Berlin regarding funding to study in Europe, but eventually he decided to return first to Harvard for his M.A. in anthropology, which he did in the fall of 1931. While studying at Harvard, Davis participated in Lloyd Warner’s research for his study of Yankee City, where he helped interview the town’s black residents. The project dissected the social life of a New England town by dividing it into six social classes, which Warner maintained were reinforced by social cliques in which one’s social class determined which cliques one had access to. Warner’s theory of social classes would significantly shape Davis’s thinking, and the two would later work together on the Deep South project.Davis went on to earn a PhD in Anthropology from the University of Chicago, where he was offered a full teaching position.Davis is depicted on a United States postage stamp issued on February 1, 1994. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a United States Navy officer.