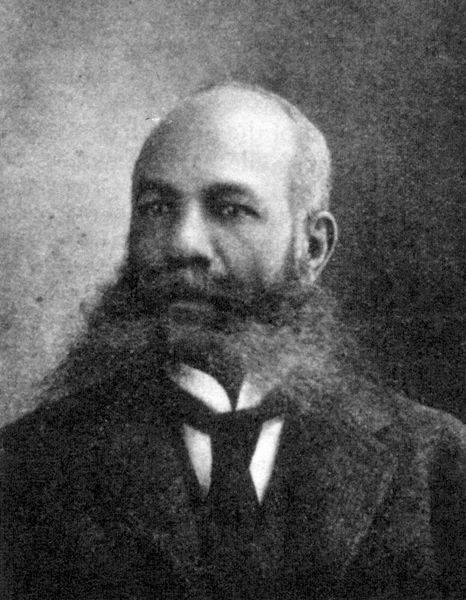

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American inventor and businessman, best known for being awarded a patent for automatically opening and closing elevator doors. Today in our History – October 11, 1887 – Alexander Miles (May 18, 1838 – May 7, 1918) – He was awarded U.S. Patent 371,207 on October 11, 1887Alexander Miles was born in Pickaway County near the town of Circleville, Ohio, in 1838, the son of Michael and Mary Miles. He was African-American. Miles may have resided in the nearby town of Chillicothe, Ohio, but subsequently moved to Waukesha, Wisconsin, where he earned a living as a barber.After a move to Winona, Minnesota, he met and married Mrs. Candace J. (Shedd) Dunlap, of La Porte, Indiana, a widow with two children, who was four years his senior and a native of New York. Together they had a daughter, born in 1876, named Grace. It is believed by some that Alexander got the idea for his elevator door mechanism after Grace accidentally fell down a shaft, almost ending her life. Shortly after her birth, the family relocated to Duluth, Minnesota. Here, Alexander became the first Black member of the Duluth Chamber of Commerce. The family moved to Montgomery, Alabama by 1889, where Miles was listed in the city directories as a laborer. In 1899, he moved to Chicago where he founded The United Brotherhood as a life insurance company that would insure black people, who were often denied coverage at that time.Around 1903, they moved again, to Seattle, Washington, where he worked in a hotel as a barber. Miles died in 1918 and was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2007. In his time, doors of the elevators had to be closed manually, often by dedicated operators. If the shaft was not closed, people could fall through it leading to some horrific accidents. Miles improved on this mechanism by designing a flexible belt attachment to the elevator cage, and drums positioned to indicate if the elevator has reached a floor. The belt allowed for automatic opening and closing when the elevator reached the drums on the respective floors, by means of levers and rollers. Miles was granted a patent for this mechanism in 1887, thus greatly improving the safety and efficiency of elevators. John W. Meaker was granted a patent 13 years earlier for another related mechanism of automatic closing of elevator doors. He is a “part of a very select group” of African-American inventors and scientists. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

Month: October 2021

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American rhythm-and-blues singer, songwriter, and pianist.

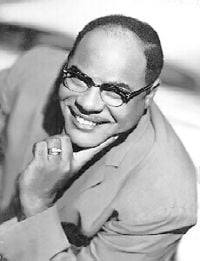

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American rhythm-and-blues singer, songwriter, and pianist. After a series of hits on the US R&B chart starting in the mid-1940s, he became more widely known for his hit recording “Since I Met You Baby” (1956). He was billed as The Baron of the Boogie, and also known as The Happiest Man Alive. His musical output ranged from R&B to blues, boogie-woogie, and country music, and he made a name in all of those genres. Uniquely, he was honored at both the Monterey Jazz Festival and the Grand Ole Opry.Today in our History – October 10, 1914 – Ivory Joe Hunter (October 10, 1914 – November 8, 1974) was born.Hunter was born in Kirbyville, Texas. Ivory Joe was his given name, not a nickname nor a stage name. As a youngster, he developed an early interest in music from his father, Dave Hunter, who played guitar, and his gospel-singing mother. He was a talented pianist by the age of 13. He made his first recording for Alan Lomax and the Library of Congress as a teenager, in 1933. Hunter was the uncle of Rick Stevens, the original lead vocalist for Tower of Power. In the early 1940s, Hunter had his own radio show in Beaumont, Texas, on KFDM, for which he eventually became program manager. In 1942 he moved to Los Angeles, joining Johnny Moore’s Three Blazers in the mid-1940s. He wrote and recorded his first song, “Blues at Sunrise”, with the Three Blazers for his own label, Ivory Records, it became a nationwide hit on the R&B chart in 1945. In the late 1940s, Hunter founded Pacific Records. In 1947, he recorded for Four Star Records and King Records. Two years later, he recorded further R&B hits; on “I Quit My Pretty Mama” and “Guess Who” he was backed by members of Duke Ellington’s band. After signing with MGM Records, he recorded “I Almost Lost My Mind”, which topped the 1950 R&B charts and would later (in the wake of Hunter’s success with “Since I Met You Baby”) be recorded by Pat Boone, whose version became a number one pop hit. “I Need You So” was a number two R&B hit that same year. With his smooth delivery, Hunter became a popular R&B artist, and he also began to be noticed in the country music community. In April 1951, he made his network TV debut on You Asked for It. He toured widely with a backing band and became known for his large build (he was 6 feet 4 inches tall), his brightly colored stage suits, and his volatile temperament.By 1954, he had recorded more than 100 songs and moved to Atlantic Records. His first song to cross over to the pop charts was “Since I Met You Baby” (1956). It was to be his only Top 40 pop song, reaching number 12 on the pop chart. While visiting Memphis, Tennessee, in the spring of 1957, Hunter was invited by Elvis Presley to visit Graceland. The two spent the day together, singing “I Almost Lost My Mind” and other songs together. Hunter commented, “He is very spiritually minded… he showed me every courtesy, and I think he’s one of the greatest.” Presley recorded several of his songs, including “I Need You So”, “My Wish Came True” and “Ain’t That Lovin’ You, Baby”. Later, Presley would record “I Will Be True” and “It’s Still Here” in May 1971. Hunter was a prolific songwriter, and some estimate he wrote more than 7,000 songs.Hunter’s “Empty Arms” and “Yes I Want You” also made the pop charts, and he had a minor hit with “City Lights” in 1959, just before his popularity began to decline. Hunter came back as a country singer in the late 1960s, making regular Grand Ole Opry appearances and recording an album titled I’ve Always Been Country. The country singer Sonny James issued a version of “Since I Met You Baby”, which topped the country charts in 1969, paving the way for Hunter’s album The Return of Ivory Joe Hunter and his appearance at the Monterey Jazz Festival. The album was recorded in Memphis with a band that included Isaac Hayes, Gene “Bowlegs” Miller and Charles Chalmers. Jerry Lee Lewis recorded a cover version of the song in 1969.Hunter died of complications due to lung cancer in 1974, at the age of 60, in Memphis, Tennessee. His remains were buried in Spring Hill Community Cemetery. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champions event started out on September 18, 1932 as a black pilot, took off from Dycer Airport, Los Angeles in an orange and black Alexander Eaglerock biplane along with his mechanic, to embark on a historic 3,000 mile journey across the U.S.A in a rickety airplane put together with surplus parts and a sputtering 14-year old Curtiss engine.

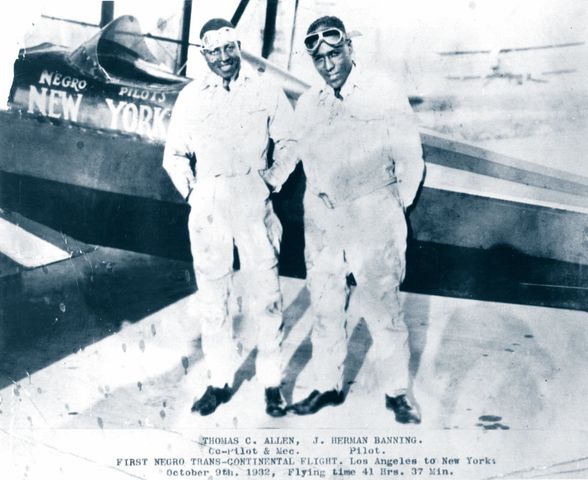

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champions event started out on September 18, 1932 as a black pilot, took off from Dycer Airport, Los Angeles in an orange and black Alexander Eaglerock biplane along with his mechanic, to embark on a historic 3,000 mile journey across the U.S.A in a rickety airplane put together with surplus parts and a sputtering 14-year old Curtiss engine. Zigzagging across the country, through Arizona and Texas, then northeast through Oklahoma, St. Louis, and Pittsburgh, PA, they reached their final destination, touching down in Valley Stream, Long Island after a total of 41 hours and 27 minutes aloft, in a span of 21 days. Today in our History – October 9, 1932 – James Banning and his mechanic Thomas C. Allen, touched down in Valley Stream, Long Island. Becoming the first African Americans to fly across the country. Fondly now called “The Flying Hobos” with a great touring play telling their story.While a total of 41 hours and 27 minutes to cross the United States by air may not seem so impressive in this day and age, one must consider the financial and societal challenges that confronted the two men over the course of the 21 day journey that made Banning’s successful flight both groundbreaking and inspiring for the next generation of African American pilots who were to follow in his path.At the height of the Great Depression with unemployment rising to 23%, some 300 thousand companies out of business and hundreds of thousands of families losing their homes, the challenge for Banning and Allen to successfully complete their trans-continental flight in 1932 was thought to be insurmountable when two black airmen, who called themselves, ‘’The Flying Hoboes’, left Los Angeles with a total of $25 between them in their pockets. But Banning’s dream of becoming the first black pilot to fly cross-country was fueled by his belief that freedom in the sky would create freedom on the ground.James Herman Banning was born in Oklahoma on November 5, 1899. His love of airplanes and dream of becoming a pilot began as a young boy in the years after the Wright Brother’s historic powered flight at Kitty Hawk in 1903 and Wilbur Wright’s subsequent flight in 1905 which covered an unprecedented 24 miles in 39 minutes and 23 seconds.In 1919 the Banning family moved to Ames, Iowa and there James enrolled at Iowa State where he studied engineering. By the spring of 1920 James took his first airplane ride at an air circus that came to town and as his calling to fly grew, he ended his studies and made the choice to pursue aviation instead. Along with that pursuit, Banning was repeatedly denied entry into American flight schools because of the color of his skin. Eventually he learned to fly privately from an army aviator who instructed him at the Raymond Fisher Flying Field in Des Moines and from 1922 to 1928 Banning owned and operated an auto repair shop in Ames. Since no individual or flight school would lend Banning an airplane so that he could complete required solo hours, he purchased an engine from a Fisher Flying Field crashed plane and gathered automobile and airplane scraps to build his own biplane which he named “Miss Ames’. By 1927, James H. Banning became the first African American in the United States to obtain a pilot’s license, number 1324, from the U.S. Department of Commerce. (Note: Emory Malick, is believed to be the first African American male to receive an FAI (Federal International) license in 1912). Leaving Iowa for Los Angeles in 1929 Banning became the chief pilot for the Bessie Coleman Aero Club, an organization whose mission was to encourage interest in aviation among African Americans, founded by visionary black aviator, William Powell.Banning barnstormed in air circuses and in 1930 he flew Illinois representative Oscar De Priest, the first black to serve in Congress since Reconstruction, on an excursion over South Los Angeles.During the 1930s ‘Golden Age of Aviation’, record-setting flights, air racing and aviators dominated the news and wealthy financiers and corporations jumped at the opportunity to sponsor these daring flights and aviators. At the height of the Depression, when Americans sought aviation heroes to take their minds off the dire economic straits of The Depression, James Banning wanted to be one of those heroes. With that in mind, after hearing a rumor of a $1,000 prize to the first black aviator to fly across the continent, he formulated a plan to be the one to accomplish that goal. Banning, however, would have no sponsors, nor would any of the mainstream media cover his story. Undeterred and without fanfare, he sought after his own backers. Enlisting mechanic, Thomas C. Allen to accompany him on the flight, Allen came up with the idea of soliciting small donations, a warm meal, a place to overnight and money for a tank of gas, from individuals they would meet at each of the towns that they landed at along the way. Donors would inscribe their names on the wing of their airplane which Banning and Allen called ‘The Gold Book’. As they made their way across the United States, stopping at some twenty-four communities, 65 contributors signed their names into ‘The Gold Book’ and with each take-off, the hopes and blessings of their donors soared along with them. As word of their flight attempt made it into the local black press, radio and newspapers began to report their progress, drawing people to watch for their anticipated arrival. By the time ‘The Flying Hoboes’ made it to St. Louis, thousands stood by to greet them. In Pittsburgh, with increasing press coverage and Election Day approaching, Democratic party officials enlisted Banning and Allen to publicize Franklin Roosevelt’s presidential campaign by dropping some 15,000 leaflets supporting the Democratic ticket along their flight over Pennsylvania. In exchange the campaign would fund the rest of the flight, and the men’s expenses, as well as the cost of care for the flight-worn Eaglerock on its return trip to California. On October 9th, after an arduous 21-day journey, Banning, with Allen, completed the flight, landing at Curtiss Airfield in Valley Stream, Long Island. Upon their arrival New York City mayor Jimmy Walker gave them the keys to the city and a parade in their honor in Harlem. Shortly after Banning completed the flight, he wrote an article for the Pittsburgh Courier entitled, “The Day I Sprouted Wings” in which he describes his first solo flight in a plane he had assembled with his own two hands. Only three and half months after his historic trans-continental flight, on February 5, 1933, Banning, who had returned to Los Angeles, attempted to rent an airplane so that he could participate in a San Diego airshow. Refused because of his race, Banning instead participated as a passenger in a biplane, sitting in the front cockpit with a white Navy pilot at the controls. After the pilot brought the plane into a steep climb, its engine stalled and the relatively inexperienced pilot was unable to gain control of the plane, causing it to crash in front of hundreds of spectators, killing both men. Banning was 34 years old at the time of his death. But the legacy of flight that he left behind still lives on. Research more about this great American Champion event and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF _ Today’s American Champion event was only 50 years after the defeat of the British at Yorktown, most Americans had already forgotten the extensive role black people had played on both sides during the War for Independence.

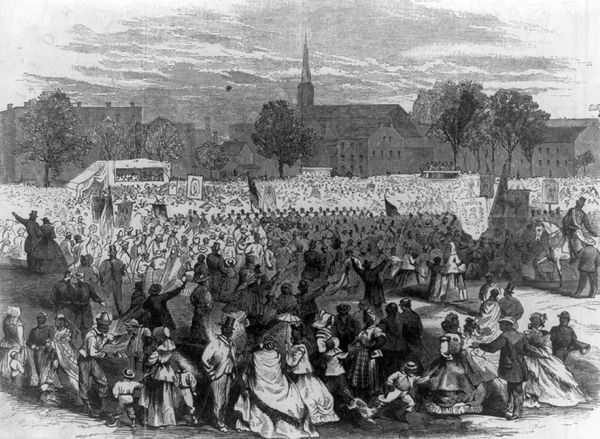

GM – FBF _ Today’s American Champion event was only 50 years after the defeat of the British at Yorktown, most Americans had already forgotten the extensive role black people had played on both sides during the War for Independence. At the 1876 Centennial Celebration of the Revolution in Philadelphia, not a single speaker acknowledged the contributions of African Americans in establishing the nation. Yet by 1783, thousands of black Americans had become involved in the war. Many were active participants, some won their freedom and others were victims, but throughout the struggle blacks refused to be mere bystanders and gave their loyalty to the side that seemed to offer the best prospect for freedom.Today in our History – October 8, 1775—Slaves and free Blacks are officially barred by the Council of Officers from joining the Continental Army to help fight for American independence from England. Nevertheless, a significant number of Blacks had already become involved in the fight and would distinguish themselves in battle. Additional Blacks were barred out of fear, especially in the South, that they would demand freedom for themselves if White America became free from Britain.African Americans and the American RevolutionBy 1775 more than a half-million African Americans, most of them enslaved, were living in the 13 colonies. Early in the 18th century a few New England ministers and conscientious Quakers, such as George Keith and John Woolman, had questioned the morality of slavery but they were largely ignored. By the 1760s, however, as the colonists began to speak out against British tyranny, more Americans pointed out the obvious contradiction between advocating liberty and owning slaves.In 1774 Abigail Adams wrote, “it always appeared a most iniquitious scheme to me to fight ourselves for what we are daily robbing and plundering from those who have as good a right to freedom as we have.”Widespread talk of liberty gave thousands of slaves high expectations, and many were ready to fight for a democratic revolution that might offer them freedom. In 1775 at least 10 to 15 black soldiers, including some slaves, fought against the British at the battles of Lexington and Bunker Hill. Two of these men, Salem Poor and Peter Salem, earned special distinction for their bravery. By 1776, however, it had become clear that the revolutionary rhetoric of the founding fathers did not include enslaved blacks. The Declaration of Independence promised liberty for all men but failed to put an end to slavery; and although they had proved themselves in battle, the Continental Congress adopted a policy of excluding black soldiers from the army.In spite of these discouragements, many free and enslaved African Americans in New England were willing to take up arms against the British. As soon states found it increasingly difficult to fill their enlistment quotas, they began to turn to this untapped pool of manpower. Eventually every state above the Potomac River recruited slaves for military service, usually in exchange for their freedom. By the end of the war from 5,000 to 8,000 blacks had served the American cause in some capacity, either on the battlefield, behind the lines in noncombatant roles, or on the seas.By 1777 some states began enacting laws that encouraged white owners to give slaves for the army in return for their enlistment bounty, or allowing masters to use slaves as substitutes when they or their sons were drafted. In the South the idea of arming slaves for military service met with such opposition that only free blacks were normally allowed to enlist in the army.Most black soldiers were scattered throughout the Continental Army in integrated infantry regiments, where they were often assigned to support roles as wagoners, cooks, waiters or artisans. Several all-black units, commanded by white officers, also were formed and saw action against the British. Rhode Island’s Black Battalion was established in 1778 when that state was unable to meet its quota for the Continental Army. The legislature agreed to set free slaves who volunteered for the duration of the war, and compensated their owners for their value.This regiment performed bravely throughout the war and was present at Yorktown where an observer noted it was “the most neatly dressed, the best under arms, and the most precise in its maneuvers.”Although the Southern states were reluctant to recruit enslaved African Americans for the army, they had no objections to using free and enslaved blacks as pilots and able-bodied seaman. In Virginia alone, as many as 150 black men, many of them slaves, served in the state navy.After the war, the legislature granted several of these men their freedom as a reward for faithful service. African Americans also served as gunners, sailors on privateers and in the Continental Navy during the Revolution. While the majority of blacks who contributed to the struggle for independence performed routine jobs, a few, such as James Lafayette, gained renown serving as spies or orderlies for well-known military leaders.Black participation in the Revolution, however, was not limited to supporting the American cause, and either voluntarily or under duress thousands also fought for the British. Enslaved blacks made their own assessment of the conflict and supported the side that offered the best opportunity to escape bondage. Most British officials were reluctant to arm blacks, but as early as 1775, Virginia’s royal governor, Lord Dunmore, established an all-black “Ethiopian Regiment” composed of runaway slaves. By promising them freedom, Dunmore enticed over 800 slaves to escape from “rebel” masters. Whenever they could, enslaved blacks continued to join him until he was defeated and forced to leave Virginia in 1776. Dunmore’s innovative strategy met with disfavor in England, but to many blacks the British army came to represent liberation. Research more about this great American Tragity and share it with your babies. Make it a chqmpion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African-American politician in South Carolina during the Reconstruction era.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African-American politician in South Carolina during the Reconstruction era. A Republican, he was elected to the state legislature in 1870 and as Secretary of State in 1872. While serving as secretary of state in 1873, He enrolled as the first student of color in the University of South Carolina medical school.Born into slavery, he was of mixed race; his enslaved mother was of mixed ethnicity. His father was a white planter and state politician who acknowledged Hayne and helped him get some education. October 7, 1873 – Henry E. Hayne enrolled as the first student of color in the University of South Carolina medical school. Henry E. Hayne was born in 1840 into slavery; his mixed-race mother was enslaved. His father was a white planter and state politician. His father acknowledged him and arranged for him to get some education, to provide social capital to help him in his later life.During Reconstruction, Hayne became active in the Republican Party, which had supported citizenship and suffrage for freedmen. He was elected in 1870 to represent Marion County in the South Carolina Senate. He was next elected as Secretary of State of South Carolina, serving from 1872 to 1877. The legislature had passed a new constitution in 1868 making public facilities available to all students, and while serving as secretary of state in the fall of 1873, Hayne enrolled in the medical school of the University of South Carolina, becoming the university’s first student of color.[1] He was majority white in ancestry. The event made national news and was covered by The New York Times; it described Hayne “as white as any of his ancestors”. Some faculty resigned in protest. In 1870 the university had hired its first black faculty member, Richard Greener, a recent graduate of Harvard University.After Democrats regained control of the state legislature and governor’s office in the election of 1876, in early 1877 they closed the college by legislative fiat. The Assembly passed a law prohibiting blacks from admission to the college, and authorized Claflin College in Orangeburg as the only institution for higher education for African Americans in the state. Hayne completed his education elsewhere.South Carolina’s electoral politics provided unique venues for Black empowerment during Reconstruction. Though largely overlooked in the historiography, the state’s flagship institution, the University of South Carolina, was a crucial piece of its Reconstruction philosophy. By 1868, legislators and university trustees radically altered their approach to higher education by expanding student scholarships and declaring it was a “tuition-free” institution open to all, regardless of race or class. These adjustments allowed Black men to matriculate by 1873, and they eventually comprised the majority of students until it was resegregated in 1877. This article reviews the Reconstruction government’s policies toward educational equality, the public response to the governmental shifts, and how students viewed their time at the institution. I reveal how African American politics in South Carolina directly intersected with educational concerns throughout the Reconstruction period. I conclude the essay by exploring how this historical moment was remembered or denied by subsequent generations.Legislator, secretary of state. Hayne was born on December 30, 1840, in Charleston, the son of a white father, James Hayne, and his free black wife, Mary. He was the nephew of Robert Y. Hayne, a former U.S. senator and governor of South Carolina. Henry Hayne was educated in Charleston and worked in the city as a tailor. With the outbreak of the Civil War, he volunteered for the Confederate army, but with the intention of escaping to Union lines. In July 1862 he crossed through enemy lines and joined Union forces, enlisting at Beaufort in the Thirty-third Regiment of United States Colored Troops (First South Carolina Volunteers), commanded by Thomas Wentworth Higginson. Enlisting as a private, Hayne was promoted to commissary sergeant in 1863.Following his discharge in early 1866, Hayne moved to Marion County. In 1868 the Freedmen’s Bureau hired him as principal of Madison Colored School, and he later served as a subcommissioner for the South Carolina Land Commission from 1869 to 1871. He served on the Republican state executive committee in 1867 and represented Marion County in the 1868 state constitutional convention. He was chairman of the Marion County Republican Party in 1870 and vice president of the state Union League. He represented Marion County in the state Senate from 1868 to 1872, and as South Carolina’s secretary of state from 1872 to 1877. As secretary of state, he took charge of the land commission and was credited for bringing honest and efficient leadership to what had previously been a notoriously mismanaged program.In 1873 Hayne enrolled in the medical school at the University of South Carolina. Though he left before earning his degree, Hayne was the first black student in the school’s history and inaugurated the institution’s first attempt at integration, which lasted until 1877.The Republican Party renominated him for secretary of state in 1876. He also served as a member of the state board of canvassers, which certified a Republican victory in the hotly contested election of 1876. The state supreme court, however, found the board to be in contempt, and jailed its members for a time. On May 3, 1877, under intense pressure, Hayne gave up his position as secretary of state to the Democratic candidate, Robert Moorman Sims.Little is known about Hayne’s personal life. He reportedly married on April 29, 1874, but the name of his wife was not given. Sometime before August 1877, Hayne left South Carolina. In January 1885 he was living in Cook County, Illinois with his wife Anna M. His later whereabouts are unknown. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

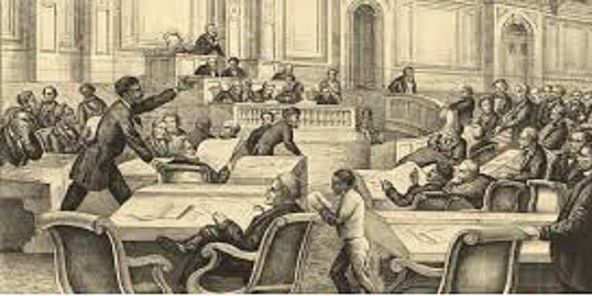

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champions were the first 33 African-American members of the Georgia General Assembly who were elected to office in 1868, during the Reconstruction era.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champions were the first 33 African-American members of the Georgia General Assembly who were elected to office in 1868, during the Reconstruction era. They were among the first African-American state legislators in the United States. Twenty-four of the members were ministers.After most of the legislators voted for losing candidates in the legislature’s elections for the U.S. Senate, the white majority conspired to remove the black and mixed-ethnicity members from the Assembly. Most of the black delegates to the state’s post-war constitutional convention voted against including into the constitution the right of black legislators to hold office, a vote which Rep. Henry McNeal Turner came to regret.The members were expelled by September 1868. The ex-legislators petitioned the federal government and state courts to intervene. In White v. Clements (June 1869), the Supreme Court of Georgia ruled 2-1 that black people did have a right to hold office in Georgia. In January 1870, commanding general of the District of Georgia Alfred H. Terry began “Terry’s Purge”, removing ex-Confederates from the General Assembly, replacing them with Republican runners-up and reinstating the black legislators, resulting in a Republican majority in both houses. From that point, the General Assembly accomplished the ratification of the 15th Amendment, chose new senators to go to Washington, and adopted public education.The work of the Republican majority was short-lived, after the “Redeemer” Democrats won majorities in both houses in December 1870. The Republican governor, Rufus Bullock, after trying and failing to reinstate federal military rule in Georgia, fled the state. After the Democrats took office they began to enact harsh recriminations against Republicans and African Americans, using terror, intimidation, and the Ku Klux Klan, leading to disenfranchisement by the 1890s. One quarter of the black legislators were killed, threatened, beaten, or jailed. The last African-American legislator, W. H. Rogers, resigned in 1907. Afterwards, no African American held a seat in the Georgia legislature until civil rights attorney Leroy Johnson, a Democrat, was elected to the state senate in 1962.The 33 are commemorated in the sculpture Expelled Because of Color on the grounds of the Georgia State Capitol.Today in our History – October 6, 1868 – The “Original 33” were the first 33 African-American members of the Georgia General Assembly who were elected to office in 1868, during the Reconstruction era.Black men participated in Georgia politics for the first time during Congressional Reconstruction (1867-76). Between 1867 and 1872 sixty-nine African Americans served as delegates to the constitutional convention (1867-68) or as members of the state legislature. Jefferson Franklin Long, a tailor from Bibb County, sat in the U.S. Congress from December 1870 to March 1871. The three most prominent Black state legislators were Henry McNeal Turner, Tunis Campbell, and Aaron A. Bradley.Turner came to Georgia from Washington, D.C., in 1865 to win Black congregations to the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). He was the most successful Black politician in organizing the Black Republican vote and attracted other ministers into politics. He was a delegate to the Georgia constitutional convention of 1867 and was elected to two terms in the Georgia legislature, beginning in 1868.Campbell, a native of New Jersey, was a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. In 1864 he was appointed an agent of the Freedmen’s Bureau on the Georgia Sea Islands. He later moved to the mainland. In 1867 he was elected to the state constitutional convention. The next year he became a state senator from the Second Congressional District. He built an impressive political machine in and around Darien in McIntosh County.Born in South Carolina, Bradley was a shoemaker in Augusta. Sometime around 1834 he ran away to the North, where he became a lawyer. In 1865 he returned to Georgia. He was the most outspoken member of the Black delegation to the constitutional convention. In 1868 he was elected state senator from the First District. Despite a checkered past, he rallied plantation workers around Savannah with his insistence that the formery enslaved people be given land.The church, with the enthusiastic support of Black women, who were still disenfranchised, was the center of African American political activity. Twenty-four legislators were ministers.However, religion, with its emphasis on the other world, predisposed some Black politicians to become too conciliatory. Most Black delegates to the constitutional convention voted against including in the constitution the right of Blacks to hold office. Turner later bitterly regretted that vote.In September 1868 the legislature, dominated by Republicans, expelled its African American members. Energized, the Black legislators, led by Turner, successfully lobbied the federal government to reseat them. They continued to concentrate on political and civil rights. For many of them, education had been their highest priority since 1865. With their solid support, Georgia adopted public education.Conservatives used terror, intimidation, and the Ku Klux Klan to “redeem” the state. One quarter of the Black legislators were killed, threatened, beaten, or jailed. In the December 1870 elections the Democrats won an overwhelming victory. In 1906 W. H. Rogers from McIntosh County was the last Black legislator to be elected before Black voters were legally disenfranchised in 1908. In 1976, the Original 33 were honored by the Black Caucus of the Georgia General Assembly with a statue that depicts the rise of African-American politicians. It is on the grounds of the Georgia State Capitol in Atlanta.The “Expelled Because of Their Color” monument is located near the Capitol Avenue entrance of the Georgia State Capitol. It was dedicated to the 33 original African-American Georgia legislators who were elected during the Reconstruction period. In the first election (1868) after the Civil war, blacks were allowed to vote. But even though former slaves could now vote, there was no law that allowed black representatives to hold office. So, the 33 black men who were elected to the General Assembly were expelled. The construction of this monument was funded by the Black Caucus of the Georgia General Assembly, a group of African-American State representatives and senators who are committed to the principles and ideals of the Civil Rights Movement organized in 1975. The Georgia Legislative Black Caucus commissioned the sculpture in March 1976 (Boutwell). John Riddle, the Sculptor of this monument, was also a painter and printmaker known for artwork that acknowledged the struggles of African-Americans through history.Inscribed on the base of Riddle’s sculpture are the names of the 33 black pioneer legislators of the Georgia General Assembly elected and expelled in 1868 and reinstated in 1870 by an Act of Congress.The Georgia Legislative Black Caucus continues to hold annual events honoring the Original 33. Research more about these great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM –FBF –Today’s American Champion an American politician and lawyer from California.

GM –FBF –Today’s American Champion an American politician and lawyer from California. She was the first African-American woman to represent the West Coast in Congress. She served in the U.S. Congress from 1973 until January 1979. She was the Los Angeles County Supervisor representing the 2nd District (1992–2008). She has served as the Chair three times (1993–94, 1997–98, 2002–03). Her husband is William Burke, a prominent philanthropist and creator of the Los Angeles MarathonIn 1973, she became the first member of the U.S. Congress to give birth while in office, and she was the first person to be granted maternity leave by the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives.She currently serves on the Board of Directors of Amtrak, having been appointed to the position by President Barack Obama in 2012.Today in our HISTORY – OCTOBER 4, 1932 – Yvonne Burke was born.Burke was born on October 5, 1932, in Los Angeles, California. She earned a B.A. in political science from the University of California at Los Angeles and a juris doctorate from the University of Southern California Law School. After graduating, she found that no law firms would hire an African-American woman and so began her own private practice. In addition, she served as the state’s deputy corporation commissioner and as a hearing officer for the Los Angeles Police Commission. In 1965, after the Watts riots in Los Angeles, Burke played a key role in organizing the legal defense for those charged in the riots, and was appointed to the McCone Commission, which was charged with determining the cause of the riots.Burke began her political career as a member of the California State Assembly, representing Los Angeles’ 63rd District from 1966 to 1972. In 1972, Burke served as vice-chairperson of the 1972 Democratic National Convention, the first African-American to hold that position. She served in the U.S. House of Representatives, representing California’s 37th District from 1973 to 1975 and the 28th District from 1975 to 1979. She did not seek re-election to Congress in 1978, instead running for California attorney general, losing in the general election. In 1979, she was appointed to fill a vacancy on the L.A. County Board of Supervisors for District 4, but was defeated in her bid for a full term in 1980 and returned to practicing law. In 1992, Burke ran for and won a seat on the L.A. County Board of Supervisors for District 2, serving until her retirement in 2008. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was known as “The Father of Community Policing,” became the first African American Mayor of Houston, Texas in 1997.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was known as “The Father of Community Policing,” became the first African American Mayor of Houston, Texas in 1997.Today in our History – October 4, 1937 – Lee Patrick Brown is born in Wewoka, Oklahoma.The first African American Mayor of Houston, Texas, Lee Patrick Brown was born on October 4, 1937, in Wewoka, Oklahoma. His parents, Andrew and Zelma Brown were small farmers. A high school athlete, Brown started his professional life as a police officer in San Jose, California in 1960.That same year, he graduated from Fresno State University with his B.S. degree in criminology. In 1964, Brown earned a master’s degree in sociology from San Jose State University where he became assistant professor in 1968. At the University of California, Berkeley, he earned his master’s degree in criminology in 1968 and his PhD in 1970.Brown became chairman and professor of the Department of Administration of Justice at Portland State University in 1968. In 1972, he was appointed associate director, Institute of Urban Affairs and Research and professor of Public Administration and director of Criminal Justice programs at Howard University. In 1974, Brown was named Sheriff of Multnomah County, Oregon, and in 1976, director of the Department of Justice Services. As public safety commissioner of Atlanta, Georgia, from 1978 to 1982, Brown and his staff cracked the Atlanta Child Murders case.As Houston, Texas’ chief of police, from 1982 to 1990, Brown developed Neighborhood Oriented Policing, a program employing community policing techniques. From 1990 to 1992, he was police commissioner of New York City. President Clinton appointed Brown director of the White House Office of National Drug Policy or “Drug Czar”, a cabinet level position from 1993 to 1996.After spending some time teaching at Texas Southern University and Rice University, Brown was elected mayor of Houston, Texas, in 1998. As mayor, he was able to build the Metro light rail system, attract a new NFL team, and expand his philosophy of neighborhood oriented government.A founder of the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives (NOBLE), Brown has organized around the needs of African American police executives. Today, Brown is chairman and CEO of Brown Group International, which uses the extensive expertise of its founder to develop solutions to complex problems in public safety, homeland security, crisis management, government relations, international trade, and other concerns.The father of four grown children with his late wife, Yvonne, Brown now lives with his wife Frances in Houston. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

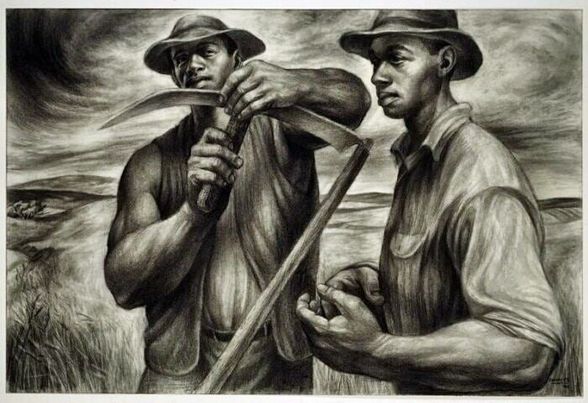

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American artist known for his chronicling of African American related subjects in paintings, drawings, lithographs, and murals.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American artist known for his chronicling of African American related subjects in paintings, drawings, lithographs, and murals. He is best known work is The Contribution of the Negro to American Democracy, a mural at Hampton University. In 2018, the centenary year of his birth, the first major retrospective exhibition of his work was organized by the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art.Today in our History – October 3, 1979 – Charles Wilbert White, Jr. (April 2, 1918 – October 3, 1979) died.Charles Wilbert White was born on April 2, 1918, to Ethelene Gary, a domestic worker, and Charles White Sr, a railroad and construction worker, on the South Side of Chicago. His parents never married and his mother raised him—as she had no child care, she would often leave him at the public library. There White developed an affinity for art and reading at a young age. White’s mother bought him a set of oil paints when he was seven years old, which hooked White on painting. White also played music as a child, studied modern dance, and was part of theatre groups; however, he stated that art was his true passion.White’s mother also took him to the Art Institute of Chicago, where he would read and look at paintings—developing a particular interest in the works of Winslow Homer and George Inness. Since White had little money growing up, he often painted on whatever surfaces he could find including shirts, cardboard, and window blinds. During the Great Depression, young White tried to conceal his passion for art in fear of embarrassment; however, this ended when White got a job painting signs at the age of fourteen. White learned how to mix paints by sitting-in every day for a week on an Art Institute sponsored painting class that as taking place at a park near his home. His mother re-married when White’s father died in 1926. She married a steel mill worker who would become an abusive alcoholic, especially towards a young White, leaving him to escape into art. This is also the same year his mother began sending him to Mississippi twice a year to his aunts, Hasty Baines and Harriet Baines, where he would learn about his heritage and African American Southern folklore – these themes would heavily influence his art for the rest of his career as an artist. An early activist, as a teenager, he volunteered his talents and became the house artist at the National Negro Congress in Chicago. Later, in a union with fellow black artists, White was arrested while picketing. White won a grant during the seventh grade to attend Saturday art classes at the Art Institute of Chicago. After reading Alain Locke’s book The New Negro: An Interpretation, a critique of the Harlem Renaissance, White’s social views changed. He learned after reading Locke’s text about important African American figures in American history, and questioned his teachers on why they were not taught to students in school, causing some to label him a “rebel problematic child”. White did not graduate from high school, having lost a year due to his refusal to attend class after being disillusioned with the teaching system. While he was encouraged by his art teachers to submit his art works and won various scholarships, these would later be taken away from him as an “error” and given to whites instead. He was admitted to two art schools, each then pulled his acceptance because of his race. White ultimately received a full scholarship to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. While there, White identified Mitchell Siporin, Francis Chapin, and Aaron Bohrod as his influences. He was an excellent draftsman, completing five drawing courses and received a final “A grade”. To pay the costs of art supplies, White became a cook, using his mother’s instruction and recipes. White later became an art teacher at St. Elizabeth Catholic High School. In 1938, White was hired by the Illinois Art Project, a state affiliate of the Works Progress Administration. His work received an extended showing at the Chicago Coliseum during the Exhibition of the Art of the American Negro, which was part of the American Negro Exposition commemorating the 75th anniversary of Thirteenth Amendment ending slavery. An important figure in what became known as the Chicago Black Renaissance, White taught art classes at the Southside Community Art Center. Following his first show at Paragon Studios in Cincinnati in 1938, White’s work was exhibited widely throughout the United States, including, among many others, exhibitions at the Roko Gallery, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. In 1939 he produced his WPA mural Five Great American Negroes, now at Howard University Gallery of Art. White also showed at the Palace of Culture in Warsaw and the Pushkin Museum. In 1976 his work was featured in Two Centuries of Black American Art, LACMA’s first exhibition devoted exclusively to African-American Artists. White moved to New Orleans in 1941 to teach at Dillard University. Beginning in that year, he was married briefly to famed sculptor and printmaker Elizabeth Catlett, who also taught at Dillard. He served in the US Army during WWII, but was discharged when he contracted tuberculosis (TB). White and Catlett moved to New York City and also studied together at an arts collective in Mexico City. While in New York City White learned lithography and etching techniques at the Arts Student League, taking direction from renowned artist Harry Sternberg who encouraged him to move beyond “stylization to individuation in his figures”. Taking Sternberg advice to heart White would go on to paint The Contribution of the Negro to American Democracy. Printmaking enabled White to reach a wider public more directly and allowed him to bring together his social commitment and artistic practice. Although he had long been aware of art’s social utility, with his lithographs and linocuts he was finally able to communicate with a large, cross-national community of black workers and socialist artists, as opposed to his paintings, which were generally tied to individual purchasers. He started providing political cartoons for the Daily Worker and, in 1953, he published in association with Masses and Mainstream a portfolio of six reproductions of his ink-and-charcoal drawings, entitled ‘Charles White: Six Drawings’. Priced at only $3, this portfolio aimed at getting art to the people, a main concern for progressive artists of the period. In this respect it was a great success, and White himself acknowledged this as he learned that a group of workers in Alabama combined their savings to buy a portfolio and shared the pictures among themselves. In 1956, due to continued breathing problems (perhaps arising from the earlier case of TB), White moved to Los Angeles for its drier, more mild climate. From 1965 to his death in 1979, White taught at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles. On faculty at Otis, he was a beacon for African American artists who came to study with him. Among those he taught were Alonzo Davis, David Hammons, and Kerry James Marshall. An elementary school was named after him and is located on the former Otis College campus. Later in life White moved to Altadena, California where he remained until his death in 1979.White’s best known work is the mural The Contribution of the Negro to American Democracy at Hampton University. Measuring around 12 feet by seven feet, the mural depicts a number of notable African-Americans including Denmark Vesey, Nat Turner, Peter Salem, George Washington Carver, Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and Marian Anderson. White was elected to the National Academy of Design in 1972.White’s works are in the collections of a number of institutions, including Atlanta University, the Barnett Aden Gallery, the Deutsche Academie der Kunste, the Dresden Museum of Art, Howard University, the Library of Congress, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Oakland Museum, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Syracuse University and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. The CEJJES Institute of Pomona, New York, owns a number of White’s works and has established a dedicated Charles W. White Gallery. White’s popularity faded after his death both because he was a person of color in an industry that unfairly favored white artists and preferred more abstract and conceptual styles in direct opposition to White’s style of figurative art. However White’s popularity and legacy lives on in Altadena, California where he spent a great deal of his later years. Shortly after his death a park was re-named after him and it remains today the only park to be named after an American born artist. The Charles White Park hosted an annual event “Charles White Memorial Arts Festival” which brought African American and local artists into the community until its discontinuation in the 1990s. Currently members of the Altadena Arts council are working with local community and other stake holders to bring the event back to the community. In 1982 a retrospective exhibition of White’s work was held at the Studio Museum in Harlem. In the 1990s, the idea of staging a major traveling retrospective exhibition arose. Ultimately, over approximately a ten year period, staff from the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art attempted to locate various White pieces to put together an extensive exhibition of his work. The exhibition opened in Chicago in 2018, traveling to New York City and Los Angeles. White “was a humanist, drawn to the physical body and more literal representations of the lives of African-Americans”, according to Lauren Warnecke for the Chicago Tribune. While this put him out of step with the abstract movement in art, the power of his work is undeniable according to the Los Angeles Times’ Christopher Knight, especially White’s graphic work in graphite, charcoal, crayon and ink. The Washington Post art critic, Philip Kennicott finds White’s work central to American art. “Grace, passion, coolness, toughness, [and] beauty” mark White’s work, according to Holland Cotter in The New York Times; White had “the hand of an angel” and “the eye of a sage”.In November 2019, two works by White went up for the first time in Christie’s and Sotheby’s main-seasonal New York City contemporary art auctions. Both works, Banner for Willie J. (1976) — a portrait of White’s cousin, who was killed—and Ye Shall Inherit the Earth (1953) — a charcoal drawing of civil rights icon Rosa Lee Ingram with a babe-in-arms—made sales records for the artist’s work. Research more of this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

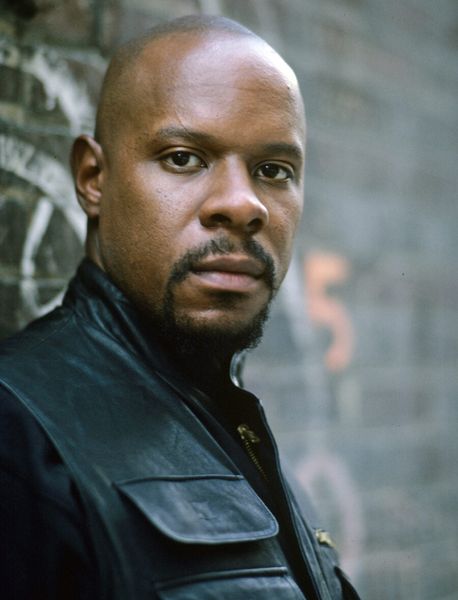

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American actor, director, singer, and educator.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American actor, director, singer, and educator. He is best known for his television roles as Captain Benjamin Sisko on Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, as Hawk on Spenser: For Hire and its spinoff A Man Called Hawk, and as Dr. Bob Sweeney in the Academy Award-nominated film American History X. While he was teaching at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J., I had the honor of sitting in his classes as an adjunct professor. I will never forget those days.Today in our History – October 2, 1948 – Avery Franklin Brooks (born October 2, 1948 was born.Avery Brooks was born in Evansville, Indiana, the son of Eva Lydia (née Crawford), a choral conductor and music instructor, and Samuel Brooks, a union official and tool and die worker. His maternal grandfather, Samuel Travis Crawford, was also a singer who graduated from Tougaloo College in 1901. When Avery was eight years old his family moved to Gary, Indiana, after his father had been laid off from International Harvester. Brooks has said: “I was born in Evansville… but it was Gary, Indiana that made me.”The Brooks household was filled with music. His mother, who was among the first African-American women to earn a master’s degree in music at Northwestern University, taught music wherever the family lived. His father was in the choir Wings over Jordan, performing on CBS radio from 1937 to 1947. His maternal uncle Samuel Travis Crawford was a member of the Delta Rhythm Boys. “Music is all around me and in me, as I am in it,” Brooks has said.Brooks attended Indiana University and Oberlin College. He later completed his bachelor of arts, plus a master of fine arts from Rutgers University in 1976, becoming the first African American to receive an MFA in acting and directing from Rutgers.Spenser: for Hire: HawkIn 1985, Brooks assumed the role of Hawk on the ABC television detective series Spenser: For Hire, based on the mystery series published by Robert Parker. Hawk became a popular character, and after three seasons, Brooks in 1989 received his own, short-lived spinoff series, A Man Called Hawk.Brooks said of his role as Hawk: “I never thought of myself as the sidekick… I’ve never been the side of anything. I just assumed that I was equal.”Brooks returned to play Hawk in four Spenser television movies: Spenser: Ceremony, Spenser: Pale Kings and Princes, Spenser: The Judas Goat and Spenser: A Savage Place.Star Trek: Benjamin SiskoBrooks is best known in popular culture for his role as Commander, and later Captain, Benjamin Sisko on the syndicated science-fiction television series Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, which ran for seven seasons from 1993 to 1999.Brooks won the role of Commander Benjamin Sisko by beating 100 other actors from all racial backgrounds to become the first Black-American captain to lead a Star Trek series.In landing the role, Brooks also became the first Black-American male actor in a starring role in a first-run television drama since Clarence Williams III had starred as undercover police detective Linc Hayes in the iconic ABC “hippie” cop drama The Mod Squad from 1968 to 1973. Brooks was the second in American television history to do so since Bill Cosby co-starred with Robert Culp in the NBC spy series I Spy from 1965 to 1968. Brooks also directed nine episodes of the series, including “Far Beyond the Stars”, an episode focusing on racial injustice.Avery, like his character (Sisko), is a very complex man. He is not a demanding or ego-driven actor, rather he is a thoughtful and intelligent man who sometimes has insights into the character that no one else has thought about. He has also been unfailingly polite and a classy guy in all my dealings with him.Other rolesIn 1984, Brooks received critical praise for his featured role in PBS’s American Playhouse production of Half Slave, Half Free: Solomon Northup’s Odyssey, directed by Gordon Parks. The story chronicled the life of Solomon Northup, a free man from New York kidnapped and sold into slavery in 1841 and held until 1853, when he regained his freedom with the help of family and friends. It was adapted from Northup’s memoir, Twelve Years a Slave (1853).Brooks appeared in the 1985 television movie adaptation of Finnegan Begin Again. In 1987, he starred in the role of Uncle Tom in the Showtime production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. A third project that allowed Brooks to highlight the history of African Americans was his performance in the 1988 television movie Roots: The Gift, which featured his fellow Star Trek actors LeVar Burton, Kate Mulgrew, and Tim Russ.In 1998, he appeared in the motion picture American History X, which also stars another Star Trek actor, Jennifer Lien. He also played the role of Paris in the 1998 film The Big Hit.In animated films, he supplied the voice of King Maximus in Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child, and Nokkar in an episode of Disney’s Gargoyles.In 2001, Brooks was the voice-over and appeared in a series of IBM commercials for its software business unit. Reserach more about this great American Champion and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!