AUTOMOTIVE HISTORY – DECEMBER 7, 1955 – The Montgomery Bus Boycott The Montgomery Bus Boycott was a civil rights protest during which African Americans refused to ride city buses in Montgomery, Alabama, to protest segregated seating. The boycott took place from December 5, 1955, to December 20, 1956, and is regarded as the first large-scale U.S. demonstration against segregation.Four days before the boycott began, Rosa Parks, an African American woman, was arrested and fined for refusing to yield her bus seat to a white man. The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately ordered Montgomery to integrate its bus system, and one of the leaders of the boycott, a young pastor named Martin Luther King, Jr., emerged as a prominent leader of the American civil rights movement.In 1955, African Americans were still required by a Montgomery, Alabama, city ordinance to sit in the back half of city buses and to yield their seats to white riders if the front half of the bus, reserved for whites, was full.But on December 1, 1955, African American seamstress Rosa Parks was commuting home on Montgomery’s Cleveland Avenue bus from her job at a local department store. She was seated in the front row of the “colored section.”When the white seats filled, the driver, J. Fred Blake, asked Parks and three others to vacate their seats. The other Black riders complied, but Parks refused.She was arrested and fined $10, plus $4 in court fees. This was not Parks’ first encounter with Blake. In 1943, she had paid her fare at the front of a bus he was driving, then exited so she could re-enter through the back door, as required. Blake pulled away before she could re-board the bus.Did you know? Nine months before Rosa Parks’ arrest for refusing to give up her bus seat, 15-year-old Claudette Colvin was arrested in Montgomery for the same act. The city’s Black leaders prepared to protest until it was discovered Colvin was pregnant and deemed an inappropriate symbol for their cause.Although Parks has sometimes been depicted as a woman with no history of civil rights activism at the time of her arrest, she and her husband Raymond were, in fact, active in the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and Parks served as its secretary.Upon her arrest, Parks called E.D. Nixon, a prominent Black leader, who bailed her out of jail and determined she would be an upstanding and sympathetic plaintiff in a legal challenge of the segregation ordinance. African American leaders decided to attack the ordinance using other tactics as well.The Women’s Political Council (WPC), a group of Black women working for civil rights, began circulating flyers calling for a boycott of the bus system on December 5, the day Parks would be tried in municipal court. The boycott was organized by WPC President Jo Ann Robinson.As news of the boycott spread, African American leaders across Montgomery (Alabama’s capital city) began lending their support. Black ministers announced the boycott in church on Sunday, December 4, and the Montgomery Advertiser, a general-interest newspaper, published a front-page article on the planned action.Approximately 40,000 Black bus riders—the majority of the city’s bus riders—boycotted the system the next day, December 5. That afternoon, Black leaders met to form the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA). The group elected Martin Luther King, Jr., the 26-year-old-pastor of Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, as its president, and decided to continue the boycott until the city met its demands.Initially, the demands did not include changing the segregation laws; rather, the group demanded courtesy, the hiring of Black drivers, and a first-come, first-seated policy, with whites entering and filling seats from the front and African Americans from the rear.

Author: Herry Chouhan

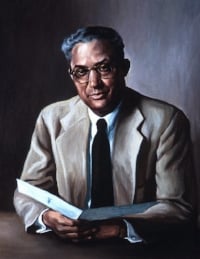

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American dermatologist, medical researcher, and philanthropist.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American dermatologist, medical researcher, and philanthropist. He was a skin specialist and is known for work related to leprosy and syphilis. Lawless was also involved in various charitable causes, including Jewish causes. Related to the latter, he created the Lawless Department of Dermatology in Beilinson Hospital, Tel Aviv, Israel. He received his M.D. degree from Northwestern University Medical School and was a self-made millionaire. In 1954, he won the NAACP Spingarn Medal, presented annually to an African American of distinguished achievement.Today in our History – December 6, 1892 – Theodore Kenneth (T.K.) Lawless (December 6, 1892 – May 1, 1971) died.Lawless was born December 6, 1892, in Thibodeaux, Louisiana to Alfred Lawless Jr., (a Congregational minister, instructor at Straight University, and American Missionary Association district superintendent of churches) and Harriet Dunn Lawless (a school teacher). Soon after his birth, his father moved the family to New Orleans, Louisiana. He earned $1-a-day as a boy in his first job, in a New Orleans market.Lawless attended Straight College (now, Dillard University) in New Orleans for secondary school and went from there to Talladega College in Alabama where he received an A.B. in 1914. He then attended the University of Kansas School of Medicine and Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago, from which he received his MD in 1919 and an MS in 1920.In 1920 he was named a Rosenwald Fellow in Medicine—an award targeting top black medical students—and thereby received $1,200 ($16,000 in current dollar terms). Lawless engaged in graduate studies at the Vanderbilt Clinic of Columbia Medical School and at Harvard Medical School. He held a fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital. He received further postgraduate training outside the United States at the University of Paris’s premier dermatology program at L’Hôpital St. Louis, as well as at the University of Freiburg in Germany, and the University of Vienna in Austria. He noted later that “it was a noteworthy fact in my own life experience that of the twelve letters [of recommendation for study abroad] that I received, eleven were from Jewish physicians.”After graduating in 1924, Lawless returned to Chicago to open his dermatology practice on Chicago’s South Side in a poor, black neighborhood. He became an instructor and research fellow at Northwestern University Medical School the same year and taught there as a professor of dermatology and syphilology until 1941. He helped establish the university’s first medical laboratories and established the first clinical laboratory for dermatology.Lawless performed research on syphilis, leprosy, sporotrichosis, and other skin diseases. In 1936, he helped devise a new treatment for early-stage syphilis (electropyrexia, which artificially raised a patient’s temperature, and then injected the patient with therapeutic drugs). He also developed special treatments for skin damaged by arsenical preparations, which were commonly used during the 1920s against syphilis, and was one of the first doctors to use radium to treat cancer. Between 1921 and 1941 he published ten papers on dermatology, which included studies on warts, sporotrichosis, the use of colloidal mercuric sulphide, arsenicals, the treatment of early syphilis with electrically induced fever, tinea sycosis of the upper lip, tularemia, and congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma.In 1957 Lawless was the first Black member of Chicago’s Board of Health. His professional memberships included the American Medical Association, the National Medical Association, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and in 1935 he became a diplomate of the American Board of Dermatology and Syphilology. He served as an associate examiner in Dermatology for the National Board of Medical Examiners and as a consultant for the United States Chemical Warfare Board.A shrewd investor and businessman, he became a multi-millionaire and had a remarkable business career. Lawless was director of both the Supreme Life Insurance Company and Marina City Bank. He was also a charter member, associate founder, and President of Service Federal Savings and Loan Association in Chicago.Most of his philanthropy involved starting a number of dermatology programs in Israel. Lawless donated $160,000 ($1,500,000 in current dollar terms) in 1957, spearheaded a Chicago fundraising drive for, and established the 35-bed Lawless Department of Dermatology in Beilinson Hospital (later known as the Rabin Medical Center), near Tel Aviv, Israel. He also created the T. K. Lawless Student Summer Camp Program for Talented Children for the scientific training for Israeli children at the Weizmann Institute of Science, in Rehovot, Israel; the Lawless Clinical and Research Laboratory in Dermatology of the Hebrew Medical School in Jerusalem, Israel. He became well acquainted with Chaim Weizmann, Israel’s first President. He thus repaid support received from Jewish doctors in obtaining his appointment to his position at the University of Paris. In 1969 he said: “I’m simply trying to repay a debt of gratitude.” He explained his philanthropy for Israel and Jewish causes by pointing out that when he was a child in New Orleans, a Jewish peddler there was always kind to his family, a Jewish professor (Maurice Lenz) had helped him at Columbia University, and he also recalled another Jewish friend. In the 1960s, he worked for the Israel Bonds drive and purchased a large number of the bonds. In December 1967, on his fifth trip to Israel, he made a donation establishing a fund to repair and restore ancient Biblical archeological discoveries at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, his fifth project in Israel.Lawless also supported Roosevelt University’s Chemical Laboratory and Lecture Auditorium, in Chicago, and Lawless Memorial Chapel at Dillard University, in New Orleans. In 1959, he was elected President of the Dillard University Board of Trustees. In 1967, the ground was first broken for the Theodore K. Lawless Gardens, in his honor and of which he was a principal, a 13-acre 514-unit middle-income housing project at 35th and Rhodes Avenue on Chicago’s South Side. He also served as Chairman of the Board of Trustees of Talladega College, Chairman of the American Missionary Association and Division of Higher Education of the Congregational and Christian Church, and Director of Youth Services of the B’nai B’rith Foundation.He died in Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago at age 78 on May 1, 1971. Lawless left $150,000 ($1,000,000 in current dollar terms) of his $1.25 million ($8,000,000 in current dollar terms) estate to the American Committee of the Weizmann Institute, a New York research institution.Lawless won the Harmon Award in Science for outstanding work in medicine in 1929.In 1954, Lawless won and became the 39th recipient of the NAACP Spingarn Medal, presented annually to a Black American of distinguished achievement, for his contributions as a “physician, educator and philanthropist”. In 1963 he received Roosevelt University’s second annual Daniel H. Burnham Award. Phi Beta Kappa honored him with its Distinguished Service Award in 1966 for “acts of charity and medical service”. In 1967 he received the University of Kansas Distinguished Service Citation and the City of Hope Golden Torch Award. In 1970 he received the Beatrice Caffrey Youth Service Merit Award.He also received the Citation of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, and the Greater Chicago Churchman Layman-of-the-Year Citation.Lawless received honorary degrees from Talldega (D.Sc.), Howard University (D.Sc.), Bethune-Cookman College (LL.D.), the University of Illinois (LL.D.), and Virginia State University (LL.D.).He was also honored by having a county park in Cass County near Vandalia, Michigan named after him (Dr. T.K. Lawless Park). The park features a range of outdoor activities, including a 10-mile mountain bike trail, shelters, softball fields, and soccer fields.A portrait of Lawless painted by Betsy Graves Reyneau is in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution at the National Portrait Gallery. It was originally collected by the Harmon Foundation as part of a project to document noteworthy African Americans. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

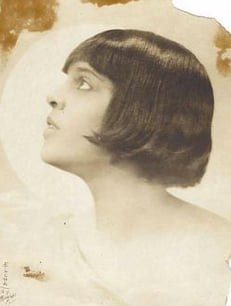

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American dancer, teacher, and boxer.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American dancer, teacher, and boxer.Today in our History – December 5, 1893 – Emma Chambers Maitland (December 5, 1893 – March 1975) was born.Jane Chambers was born near Richmond, Virginia, the daughter of Wyatt Chambers and Cora Chambers. Her parents were sharecroppers, and she had seven brothers. She was educated at a convent school at Rock Castle, Virginia, and qualified as a teacher. She changed her first name when she moved to Washington, D.C. as a young woman. Emma Maitland was a woman of many talents. She was dancer and actress but it was boxing that made her name well-known. Maitland was successful as a fighter, she earned hundreds of dollars per fight. She was later earned the title lightweight boxing champion of the worldMaitland was born in Virginia in 1893.Her parents worked as tobacco farmers. After completing her primary education, she took and passed the exam to become a teacher.Within a few years of passing the exam, Maitland relocated to Washington, D.C., where she later met her husband who was attending Howard University. The couple had a daughter, but within a year of being married, tragedy struck and her husband, Clarence Maitland, died from tuberculosis.Being left to raise her daughter alone, Maitland decided to pursue a career as a dancer. She left her child with her parents and headed to Paris to pursue a career. She traveled throughout Europe performing with a dance troupe and ended up back in the United States. She later performed in the musical Shuffle Along and later appeared in the theater production Harlem at the Apollo Theater.Chambers was a teacher as a young woman in Virginia. As a widow with a young daughter to support, Maitland moved to Paris. She danced at the Moulin Rouge, modeled for artists, and did a boxing act with another American performer, Aurelia Wheedlin (or Wheeldin). She became serious about boxing, trained with American boxer Jack Taylor, and toured with Wheedlin in Europe, billed as the world’s lightweight female boxing champion. She also boxed in Canada, Cuba and Mexico. Maitland moved back to the United States in 1926, lived in New York City, and continued performing as a “boxeuse”. She appeared (often with Wheedlin) in clubs, on vaudeville and on the New York stage in black revues, including Messin’ Around (1929), Change Your Luck (1930), and Fast and Furious (1931). She worked as a bodyguard and taught dance and gymnastics. In her later years she moved to Martha’s Vineyard. By 1927, Maitland was training as a boxer. She appeared in a boxing skit in Paris, where she and another black boxer Aurelia Wheeldin boxed three rounds. After hanging up her boxing gloves, Maitland taught dance and gymnastics in New York. Emma Maitland married a Howard University medical student, Clarence Maitland. They had a daughter together in 1917. Clarence Maitland died from tuberculosis within a year of their wedding. She died in early 1975, aged 82. Maitland donated her papers and souvenirs to the Schomburg Collection at the New York Public Library, in 1943. In 2015, Maitland’s former home in Oak Bluffs became a stop on the African American Heritage Trail of Martha’s Vineyard. In 2020, she was the subject of an exhibit at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make It A Champion Day!

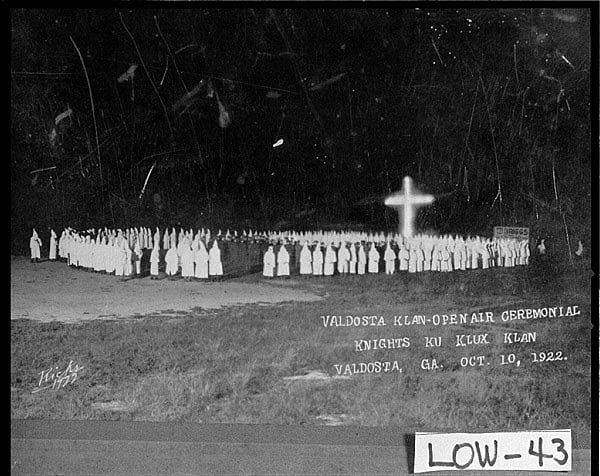

GM –FBF – Today’s American Champion event was In politics, for example, Fulton County Solicitor General John M. Boykin and Fulton Superior Court Judge Gus H.

GM –FBF – Today’s American Champion event was In politics, for example, Fulton County Solicitor General John M. Boykin and Fulton Superior Court Judge Gus H. Howard were both Klansmen. The Klan’s chief lawyer, Paul S. Etheridge, himself sat on the Fulton County Board of Commissioners of Roads and Revenues. Klansman Walter A. Sims was elected mayor of Atlanta in 1922, in a campaign centered on the prohibition of interracial worship. And after being tagged as insufficiently supportive of Klan efforts, in 1922 Georgia’s Governor Thomas Hardwick was voted out of office and replaced with ardent Klan supporter Clifford Walker.Today in our History – December 4, 1915 – The KKK receives charter to operate in Georgia.It is in cultural pursuits, though, that we see the full extent to which the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s had been absorbed into the ordinary, everyday white supremacism of life in Atlanta. Whether a member or not, you could stop at newsstands across the city to pick up a copy of the Klan’s newspaper, Searchlight. Financed by Tyler and edited by J. O. Wood (who was also a member of the state legislature), the weekly focused its reporting on the ostensible good deeds and charitable works of the Klan, mixed with local news and comment. More than sixty thousand people purportedly read Searchlight each week, and the publication carried advertisements from a wide cross-section of local businesses, including Coca-Cola.Within the pages of Searchlight, we find the vibrant cultural life of the ordinary white supremacist. For those seeking an evening’s entertainment, the citizens of Atlanta could attend a Klan-organized screening of the smash hit Birth of a Nation or one of the increasing number of the Klan’s own feature films. They could turn on the radio to listen to Klansman Fiddlin’ John Carson, or purchase one of the OKeh recordings of his music – recordings which helped create country music as a commercial genre.3 Maybe they would be lucky enough to catch the traveling stage show, The Awakening, which mingled the plot of Birth of a Nation with musical numbers and cabaret-style showgirls. Since the show relied on local amateur theater to fill its ranks as it moved from town to town, many Atlantans also appeared in the production.If readers turned instead to the sports pages of the Atlanta Constitution (where Edward Young Clarke’s brother worked as managing editor), they could find box scores for the Atlanta Klan’s baseball team. In 1924, the Klan played in the amateur Dixie League against teams including their neighbors from the Peachtree Road Presbyterian Church, Georgia West Point, and the Georgia Railroad and Power Company. In a reflection of the Klan’s immersion in everyday life, the rivalry between the Klan team and the Georgia Tech Rehabs team for the league pennant (eventually won by the Klan) garnered far more press attention than the Klan’s nonleague games against more surprising opponents, including the Catholic Knights of Columbus.4 Clearly, membership in the Invisible Empire was no bar to participation in community life.This is not to say the Klan was without controversy. Atlanta was also where the Klan’s dirty laundry was aired – where Clarke and Tyler were arrested on morals charges; where the Klan’s leading religious official, known as the “Kludd,” Caleb Ridley was arrested for drunk driving; and where the Klan’s press chief, Philip Fox, shot his rival, William S. Coburn.5 And gradually the Klan’s presence in the city lessened.As Hiram Evans wrested control of the Klan from Imperial Wizard Simmons and focused increasingly on politics, he would make Washington, DC, the new Klan headquarters. Ultimately, the Klan’s Imperial Palace would be sold off to an insurance company, who then sold the property to the Catholic Church. It is now the site of the Cathedral of Christ the King.Yet the Klan’s legacy lingers on in Atlanta. While seemingly emboldened in recent months, and the subject of rising visibility, contemporary white supremacists did not appear from nowhere. The Association of Georgia Klans, headed by Atlanta obstetrician Samuel Green, was established with another cross burning at Stone Mountain in 1945. As Green’s organization faded, it was supplanted by the U.S. Klans in the 1950s. Even as the city became an epicenter for the Civil Rights Movement, a summit just south of Atlanta saw the creation of the United Klans of America. At a 1962 Fourth of July protest at Stone Mountain, robed Klansmen mingled with other segregationists and neo-fascists from the area. Over the past decades, the Atlanta metro region has continued to provide a home for branches of the Loyal White Knights of the Klan, the Aryan Nations, and the many others who may pay no formal dues but nonetheless share white supremacist views. Just as with the men and women of the Klan in the 1920s, these men and women today are not strange, otherworldly creatures, incapable of ordinary human interests, but rather all too familiar. Examining the Klan’s past cultural endeavors reminds us of the insidious and pervasive presence white supremacism has held in everyday life. Such examinations are critical. Until we understand the deep-rooted history of that presence, we will remain unable to truly reckon with the “normal” white supremacists of today.Research more about this great American tritest group and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

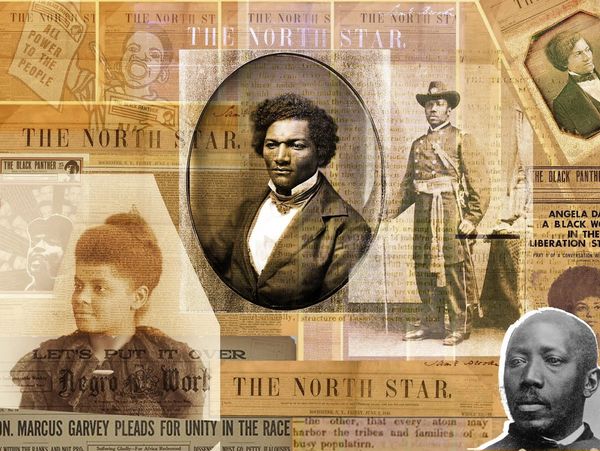

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was company was ahead of its time.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was company was ahead of its time. The North Star was a nineteenth-century anti-slavery newspaper published from the Talman Building in Rochester, New York, by abolitionist Frederick Douglass. The paper commenced publication on December 3, 1847, and ceased as The North Star in June 1851, when it merged with Gerrit Smith’s Liberty Party Paper (based in Syracuse, New York) to form Frederick Douglass’ Paper. At the time of the Civil War, it was Douglass’ Monthly. The North Star’s slogan was: “Right is of no Sex—Truth is of no Color—God is the Father of us all, and all we are Brethren.”Today In Our History – December 3, 1847 – The North Star Newspaper was born.In 1846, Frederick Douglass was first inspired to publish The North Star after subscribing to The Liberator, a weekly newspaper published by William Lloyd Garrison. The Liberator was a newspaper established by Garrison and his supporters founded upon moral principles. The North Star title was a reference to the directions given to runaway slaves trying to reach the Northern states and Canada: “Follow the North Star.” Figuratively, Canada was also “the north star.”Like The Liberator, The North Star published weekly and was four pages long. It sold by subscription of $2 per year to more than 4,000 readers in the United States, Europe, and the Caribbean. The first of its four pages focused on current events concerning abolitionist issues.The Garrisonian Liberator was founded upon the notion that the Constitution was fundamentally pro-slavery and that the Union ought to be dissolved. Douglass disagreed but supported the nonviolent approach to the emancipation of slaves by education and moral suasion.Under the guidance of the abolitionist society, Douglass became well acquainted with the pursuit of the emancipation of slaves through a New England religious perspective. Garrison had earlier convinced the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society to hire Douglass as an agent, touring with Garrison and telling audiences about his experiences as a slave. Douglass worked with another abolitionist, Martin R. Delany, who traveled to lecture, report, and generate subscriptions to The North Star.attended the National Convention of Colored Citizens, an antislavery convention in Buffalo, New York, in August 1843. One of the many speakers present at the convention was Henry Highland Garnet. Formerly a slave in Maryland, Garnet was a Presbyterian minister who supported violent action against slaveholders. Garnet’s demands of independent action addressed to the American slaves remained one of the leading issues of change for Douglass.During a nineteen-month stay in Britain and Ireland, several of Douglass’ supporters bought his freedom and assisted with the purchase of a printing press. With this assistance, Douglass was determined to begin an African-American newspaper that would engage the anti-slavery movement politically.On his return to the United States in March 1847, Douglass shared his ideas of The North Star with his mentors. Ignoring the advice of the American Anti-Slavery Society, Douglass moved to Rochester, New York to publish the first edition. When questioned on his decision to create The North Star, Douglass is said to have responded,I still see before me a life of toil and trials…, but, justice must be done, the truth must be told…I will not be silent.In covering politics in Europe, literature, slavery in the United States, and culture generally in both The North Star and Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Douglass achieved unconstrained independence to write freely on topics from the California Gold Rush to Uncle Tom’s Cabin to Charles Dickens’s Bleak House.Besides Garnet, other Oneida Institute alumni that collaborated with The North Star were Samuel Ringgold Ward and Jermain Wesley Loguen.Douglass was assisted by philanthropist Gerrit Smith. Smith later merged his own anti-slavery paper with The North Star to create Frederick Douglass’ Paper. Research more about this great American Champion and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!

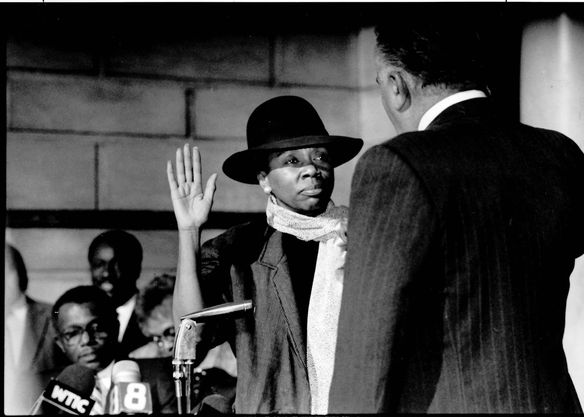

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American politician from Connecticut.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American politician from Connecticut. She was notable as the first African American woman to be elected mayor of a major New England city – Hartford, Connecticut – in 1987. She served three terms before being defeated in 1993. She served as a member of the Connecticut House of Representatives from 1980 until 1987. She was known for her distinctive broad-rimmed hats.Today in our History – December 1, 1987 – Carrie Saxon Perry (August 30, 1931 – November 22, 2018) was elected Mayor of Hartford, Connecticut.Perry was born on August 30, 1931, in Hartford to David Saxon and Mabel Lee. She was primarily raised by her grandmother after her father left the family when she was only six months old.She graduated from Howard University with a degree in economics and attended Howard University School of Law for two years before leaving school to marry James Perry, Jr. After leaving law school, she worked with a number of community organizations and help establish boards for organizations such as Planned Parenthood. She also worked for the state welfare agency.Her first run for state representative ended in defeat in 1976. She was elected in 1980 and served until her election as mayor. She was selected as an assistant majority leader, chair of the bonding subcommittee, and a committee member for education, finance, and housing.She became known for donning unique hats, of which she owned about two dozen. She said she started the habit because didn’t have time to take care of her hair.Perry was elected the mayor of Hartford at the age of 56.In 1987, Mayor Thirman L. Milner, the city’s first African American mayor, announced that he would not seek re-election to city hall. Perry entered the race and won the endorsement of the local Democratic Party. In the general election, she defeated Republican Philip Steele with 58 percent of the vote.She was credited for helping reduce racial tension in the city; notably, she visited black neighborhoods after the Rodney King verdict, which was credited with preventing rioting in Hartford as had happened in other large cities.She championed LGBT rights in Hartford during her mayorship, introducing legislation to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation in Hartford schools, 5 years before such legislation was adopted in Connecticut.She also focused on reducing burgeoning gang activity and drug trafficking, which was on the rise at the time. The position in Hartford is considered largely ceremonial and paid a stipend of $17,500.After three terms as mayor, she was defeated by first-time Democratic challenger Michael Peters, a city firefighter. He had run on a campaign capitalizing on Hartford’s declining economy and a sense that street crime was on the rise.Perry married James Perry, Jr. from whom she was divorced. She had a son, four grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.Perry died on November 22, 2018, at the age of 87. However, her death remained unreported until November 2019.Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is the 17-year-old was playing in her first grand slam quarterfinal, but trailing 4-0 in the second set, a frustrated she smashed her racquet on the clay court after she double faulted.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is the 17-year-old was playing in her first grand slam quarterfinal, but trailing 4-0 in the second set, a frustrated she smashed her racquet on the clay court after she double faulted.She ran her opponent close in the opening set, with Krejcikova needing a dramatic tiebreak to gain the upper hand in the match.In the second set, the Czech player ramped up the pressure on her younger opponent, winning the first five games without reply.Today in our History – November 29, 2020- Coco Gauff, is defeated in match and breaks racquet.But the American showed experience to belie her age, saving multiple match points and winning three straight games to make things nervy before Krejcikova claimed the second set’s decisive ninth game to reach the semifinals.”I never imagined I would be standing here one day,” the 25-year-old Krejcikova said on court after her victory.Both players were playing in their first career singles grand slam quarterfinals. By reaching the last eight, Gauff had become the youngest woman to compete in a grand slam quarterfinal since 2006.Despite her age, the 17-year-old Gauff didn’t look out of place on the big stage on Court Philippe Chatrier.The No. 24 seed held 3-0 and 5-3 leads in the opening set, but Krejcikova fought back, saving five match points before eventually taking the 72-minute set.Gauff pinpointed losing the first set as the turning point in the match.”I’m obviously disappointed that I wasn’t able to close out the first set,” she told the media after. “To be honest, it’s in the past, it already happened. After the match, my hitting partner told me this match will probably make me a champion in the future. I really do believe that.”That really seemed to kick the world No. 33 into gear.She looked much more comfortable in the second set, manipulating the ball at will, with Gauff struggling to gain any momentum.And leading 5-0 in the second set and needing just one more game to reach her first singles grand slam semifinal, that looked like a formality for Krejcikova with Gauff appearing rattled.However, Gauff showed remarkable strength and resilience to save multiple match points to win three straight games and suggest a previously unthinkable recovery might just be possible.But it was not to be and on Krejcikova’s sixth match point the Czech player clinched the match after one hour and 50 minutes.Krejcikova believes some of her singles success is down to a change in perspective during the Covid-19 shutdown.”Seeing that there are also other things in the world that actually are happening,” she said. “[That] are tougher and more difficult than just me playing tennis and losing.”It just got to my mind. I’m like, Well, I go and I play tennis and I lose, but there are actually people that are losing their lives. I just felt more like, Well, just relax because you are healthy. Just appreciate this and just enjoy the game.You can do something what maybe other people would like to do as well but they cannot.”Krejcikova will face defending champion Iga Swiatek or Greece’s Maria Sakkari for a place in the final at Roland Garros. Research more about this great American Champio and shate it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

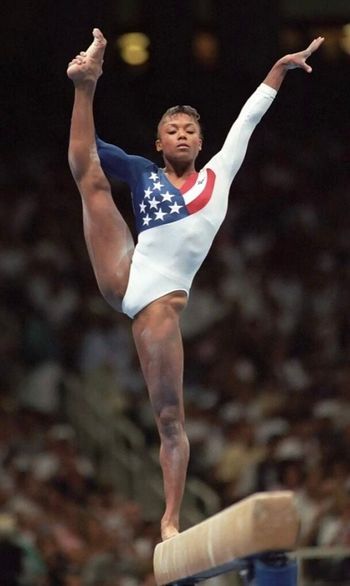

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is one of the most renowned names in the history of American gymnastics, she recognized her passion for gymnastics at an early age of 6 years and attended lessons with Kelli Hill who remained her coach for the rest of her gymnastics career.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is one of the most renowned names in the history of American gymnastics, she recognized her passion for gymnastics at an early age of 6 years and attended lessons with Kelli Hill who remained her coach for the rest of her gymnastics career.Today in our History – November 20, 1976 – Dominique Dawes was born.With her skills and determination, Dawes soon became a force to be reckoned with in the field of gymnastics and at the young age of 12, became the first African American to earn a spot in the national women’s team. In 1992, Dawes joined the U.S. Olympic artistic gymnastics team which won the bronze medal in Barcelona. In the 1994 National Championships, she won all-around gold and four individual events, vault, uneven bars, balance beam and floor exercise, becoming the first gymnast to win all five gold medals since 1969.Making the cut for the 1996 U.S. Olympic team, Dawes led the Magnificent Seven to the first position, making the squad the first U.S. women’s gymnastics team to do so in the history of Olympics. A few small mistakes, including a fall, hindered Dawes’ contention for the all-around competition medal. However, she earned herself the title of the first African American to win an individual medal in women’s gymnastics by displaying the best floor performance.Dawes successfully maintained a balance between her academic and sports careers, attending Standford University on an athletic scholarship which she had received upon graduating from Gaithersburg High School but had deferred her enrollment until after the 1996 Olympics. Being an all-rounder, she also began pursuing a career in arts around the same time, involving herself in acting, television production and modeling. Appearing in the famous Broadway musical, Grease, Dominique Dawes also worked for Disney Television and one of Prince’s music videos.Justifying to her reputation of Awesome Dawesome, Dawes continued to train while gaining higher education in 2000 and made it to U.S. Olympic team for a third time. Initially finishing in fourth place, the team was moved prized with a bronze medal after a Chinese competitor was disqualified. Thus, Dawes became the first U.S. gymnast to be a part of three different medal-winning teams and made record of the most trips to the Olympics by a female U.S. gymnast.The same year, Dawes permanently retired from gymnastics and put her efforts into other fields. Giving back to the community, Dawes served as the President of the Women’s Sports Foundation and was also a part of Michelle Obama’s ‘Let’s Move Active Schools’ campaign. In 2010, Dawes also became Co-Chair of the President’s Council on Fitness, Sports and Nutrition. The former gymnast also earned herself a spot in USA’s Gymnastics’ Hall of Fame in 2005.Encouraging young individuals to be active, Dawes gives private lessons at her home gym and holds a position on the advisory board for Sesame Workshop’s ‘Healthy Habits for Life’. Dawes also served as the National Spokesperson for Uniquely Me, the Unilever Self-Esteem program, where she gave tips to girls regarding self-esteem issues and guided them by sharing her personal experiences.Dominique Dawes maintained her connection with gymnastics by covering the 2008 and 2012 Olympic Games and witnessed Gabby Douglas become the first African American to win an individual gold medal in the all-around competition in 2012. Dawes hoped that Douglas would be able to inspire young girls and serve as their role model in a manner similar to hers. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was called all kinds of names by his own people for taking roles that projected Blacks as inferior.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was called all kinds of names by his own people for taking roles that projected Blacks as inferior. I learned from my great Uncle Leon Busby the real history and from then on I would correct people when they called our people on the screen or movies what the truth was. Today’s Champion was an American vaudevillian, comedian, and film actor of Jamaican and Bahamian descent, considered to be the first Black actor to have a successful film career. His highest profile was during the 1930s in films and on stage, when his persona of Stepin Fetchit was billed as the “Laziest Man in the World”.He parlayed the Fetchit persona into a successful film career, becoming the first Black actor to earn $1 million. He was also the first Black actor to receive featured screen credit in a film.His film career slowed after 1939 and nearly stopped altogether after 1953. Around that time, Black Americans began to see his Stepin Fetchit persona as an embarrassing and harmful anachronism, echoing negative stereotypes. However, the Stepin Fetchit character has undergone a re-evaluation by some scholars in recent times, who view him as an embodiment of the trickster archetype Today in our History – November 19, 1985 – Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry (May 30, 1902 – November 19, 1985), better known by the stage name Stepin Fetchit died.Little is known about Perry’s background other than that he was born in Key West, Florida, to West Indian immigrants. He was the second child of Joseph Perry, a cigar maker from Jamaica (although some sources indicate the Bahamas) and Dora Monroe, a seamstress from Nassau, The Bahamas.Both of his parents came to the United States in the 1890s, where they married. By 1910, the family had moved north to Tampa, Florida. Another source says he was adopted when he was 11 years old and taken to live in Montgomery, Alabama.His mother wanted him to be a dentist, so Perry was adopted by a quack dentist, for whom he blacked boots before running away at age 12 to join a carnival. He earned his living for a few years as a singer and tap dancer.In his teens, Perry became a comic character actor. By the age of 20, Perry had become a vaudeville artist and the manager of a traveling carnival show. His stage name was a contraction of “step and fetch it”. His accounts of how he adopted the name varied, but generally he claimed that it originated when he performed a vaudeville act with a partner.Perry won money betting on a racehorse named “Step and Fetch It”, and his partner and he decided to adopt the names “Step” and “Fetchit” for their act. When Perry became a solo act, he combined the two names, which later became his professional name.Perry played comic-relief roles in a number of films, all based on his character known as the “Laziest Man in the World”. In his personal life, he was highly literate and had a concurrent career writing for The Chicago Defender.He signed a five-year studio contract following his performance in the film, In Old Kentucky (1927). The film’s plot included a romantic connection between Perry and actress Carolynne Snowden, a subplot that was a rarity for Black actors appearing in a White film during this era. Perry also starred in Hearts in Dixie (1929), one of the first studio productions to boast a predominantly Black cast.Jules Bledsoe provided Perry’s singing voice for his role as Joe in the 1929 version of Show Boat. Fetchit did not sing “Ol’ Man River”, but he did sing “The Lonesome Road” in the film. In 1930, Hal Roach signed him to a film contract to appear in nine Our Gang episodes in 1930 to 1931. He was in the 1929-30 film A Tough Winter; his contract was cancelled after its release.Perry was good friends with fellow comic actor Will Rogers.[4] They appeared together in David Harum (1934), Judge Priest (1934), Steamboat ‘Round the Bend (1935), and The County Chairman (1935).By the mid-1930s, Perry was the first Black actor to become a millionaire. He appeared in 44 films between 1927 and 1939. In 1940, Perry temporarily stopped appearing in films, having been frustrated by his unsuccessful attempt to get equal pay and billing with his White costars. He returned in 1945, in part due to financial need, though he only appeared in eight films between 1945 and 1953.He declared bankruptcy in 1947, stating assets of $146 (equrato about $1,692 today) He returned to vaudeville; he appeared at the Anderson Free Fair in 1949 alongside Singer’s Midgets. He became a friend of heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali in the 1960s, converting to the Nation of Islam shortly before.After 1953, Perry appeared in cameos in the made-for-television movie Cutter (1972) and the feature films Amazing Grace (1974) and Won Ton Ton, the Dog Who Saved Hollywood (1976). He found himself in conflict during his career with civil rights leaders who criticized him personally for the film roles that he portrayed.In 1968, CBS aired the hour-long documentary Black History: Lost, Stolen, or Strayed, written by Andy Rooney (for which he received an Emmy Award) and narrated by Bill Cosby, which criticized the depiction of blacks in American film, and especially singled out Stepin Fetchit for criticism. After the show aired, Perry unsuccessfully sued CBS and the documentary’s producers for defamation of character.In late November 1963, Perry collaborated with Motown Records founder Berry Gordy Jr. and Esther Gordy Edwards in composing “May What He Lived for Live,” a song intended to honor the memory of President John F. Kennedy in the wake of his assassination.Perry was credited under the pseudonym W.A. Bisson. The song was recorded in December 1963 by Liz Lands, who in 1968 performed the work at the funeral of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.Fetchit has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.In 1976, despite popular aversion to his character, the Hollywood chapter of the NAACP awarded Perry a special NAACP Image Award. Two years later, he was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame.Perry spawned imitators, such as Willie Best (“Sleep ‘n Eat”) and Mantan Moreland, the scared, wide-eyed manservant of Charlie Chan. Perry had actually played a manservant in the Chan series before Moreland in 1935’s Charlie Chan in Egypt.)Perry appeared in one 1930 Our Gang short subject, A Tough Winter, at the end of the 1929–30 season. Perry signed a contract to star with the gang in nine films for the 1930–31 season and be part of the Our Gang series, but for some unknown reason, the contract fell through, and the gang continued without Perry.Previous to Perry entering films, the Our Gang shorts had employed several Black child actors, including Allen Hoskins, Jannie Hoskins, Ernest Morrison, and Eugene Jackson. In the sound Our Gang era black actors Matthew Beard and Billie Thomas were featured. The Black performers’ personas in Our Gang shorts were the polar opposites of Perry’s persona.Gordon Lightfoot referenced Stepin Fetchit in his 1970 song “Minstrel of the Dawn” on the album Sit Down Young Stranger.In the 2005 book Stepin Fetchit: The Life and Times of Lincoln Perry, African-American critic Mel Watkins argued that the character of Stepin Fetchit was not truly lazy or simple-minded, but instead a prankster who deliberately tricked his White employers so that they would do the work instead of him.This technique, which developed during American slavery, was referred to as “putting on old massa”, and it was a kind of con art with which Black audiences of the time would have been familiar.In 1929, Perry married 17-year-old Dorothy Stevenson. She gave birth to their son, Jemajo, on September 12, 1930. In 1931, Dorothy filed for divorce, stating that Perry had broken her nose, jaw, and arm with “his fists and a broomstick.” A few weeks after their divorce was granted, Dorothy told a reporter she hoped someone would “just beat the devil out of him,” as he had done to her. When Dorothy contracted tuberculosis in 1933, Perry moved her to Arizona for treatment. She died in September 1934.Perry reportedly married Winifred Johnson in 1937, but no record of their union has been found. On May 21, 1938, Winifred gave birth to a son she named Donald Martin Perry. Their relationship ended soon after Donald’s birth.According to Winifred’s brother Stretch Johnson, their father intervened after Perry knocked Winifred down the stairs and broke her nose. In 1941, Perry was arrested after Winifred filed a suit for child support. When he was released from jail, he told reporters, “Winnie and I were never married.It was all a publicity stunt. I want you and everybody else to know that that is not my baby. Winnie knows the baby isn’t mine but she’s trying to be smart.” Winifred admitted that they were not legally married, but she insisted Perry was her son’s father. The court ruled in her favor and ordered Perry to pay $12 a week (almost $220 in 2020 dollars) for the child’s support. Donald later took his stepfather’s surname, Lambright.Perry married Bernice Sims on October 15, 1951. Although they separated by the mid-1950s, they remained married for the rest of their lives. Bernice died on January 9, 1985.On April 5, 1969, Donald Lambright traveled the Pennsylvania Turnpike shooting people. Reportedly, he injured 16 and killed four, including his wife, with an M1 carbine and a .30-caliber Marlin 336 carbine before turning one of the rifles on himself.The 1969 Pennsylvania Turnpike shooting was ruled a murder-suicide, but the account of the circumstances upon which the ruling was based was questioned by Lambright’s daughter and discussed at length in her 2005 self-published book about Stepin Fetchit.In a Los Angeles Times interview, Lincoln Perry stated his belief that his son was set up. Lambright’s involvement with the Black Power movement at the peak of the COINTELPRO program was believed to be related to his death. Perry never provided child support for Lambright, and they only met two years before his son’s violent death.Perry suffered a stroke in 1976, ending his acting career; he then moved into the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital. He died on November 19, 1985, from pneumonia and heart failure at the age of 83.He was buried at Calvary Cemetery in East Los Angeles with a Catholic funeral Mass. Research more about this great American Champion and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!

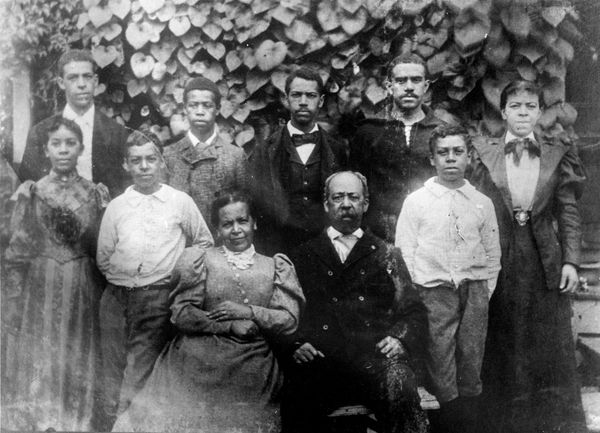

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a former slave and veteran of the American Civil War, serving in the U.S. Navy.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a former slave and veteran of the American Civil War, serving in the U.S. Navy. His diary is one of only a few written during the Civil War by former slaves that have survived, and then only by a formerly enslaved sailor.Today in our History – November 18, 1837 – William Benjamin Gould (November 18, 1837 – May 25, 1923) was born.William B. Gould was born in Wilmington, North Carolina on November 18, 1837, to an enslaved woman, Elizabeth “Betsy” Moore, and Alexander Gould, an English-born resident of Granville County, NC. He was enslaved by Nicholas Nixon, a peanut farmer who owned Poplar Grove, a plantation on Porters Neck. Gould worked as a plasterer at the antebellum Bellamy Mansion in Wilmington, North Carolina, and carved his initials into some of the plaster there.The outbreak of the Civil War brought danger to Wilmington in the form of crime, disease, the threat of invasion, and “downright bawdiness.” This prompted many slave owners to move inland, resulting in less supervision over those they were enslaving. During a rainy night on September 21, 1862, Gould escaped with seven other enslaved men by rowing a small boat 28 nautical miles (52 km) down the Cape Fear River. They embarked on Orange Street, just four blocks from where Gould lived on Chestnut St. Sentries were posted along the river, adding additional danger. The boat had a sail, but they did not raise it until they were out in the Atlantic for fear of being seen.Just as the dawn was breaking on September 22, they rushed out into the Atlantic Ocean near Fort Caswell and hoisted their sail. There, the USS Cambridge of the Union blockade picked them up as contraband. Other ships in the blockade picked up two other boats containing friends of Gould in what may have been a coordinated effort. Though Gould had no way of knowing it, within an hour and a half of his rescue President Abraham Lincoln convened a meeting of his cabinet to finalize plans to issue the Emancipation Proclamation.During the war, his home was burned, and with it a family Bible. His birthday was inscribed in that Bible but that was the only record of his birth.There had been some concern about the numbers of slaves who were escaping and making it to Union ships before Gould’s escape. One captain had written to the Navy Department asking what was to be done with them as they did not have room for the extra men.William A. Parker, the captain of the Cambridge, however, had written to Acting Rear Admiral Samuel Phillips Lee just five days before picking up Gould that his ship was short 18 men due to desertions and sickness. As a result, he said, he intended to fill the vacancies with escaped slaves.After his boarding, the Cambridge, Gould notes that he was “kindly received by officers and men.” In his diary, he noted that on October 3, 1862, he took “the Oath of Allegiance to the Government of Uncle Samuel.” Upon joining the U.S. Navy onboard the Cambridge, he was given the rank of First Class Boy.At the time, boy was the highest rank a black sailor could earn. He was later promoted to landsman and then wardroom steward, making him a petty officer but without the authority that came as an officer of the line.The Cambridge was part of the Atlantic Blockading Squadron, enforcing the blockade of the Confederate coastline. Gould found the work to be difficult and lonely, recording after just three months on the ship that all the men had the blues. Still, Gould believed he was “defending the holiest of all causes, Liberty and Union.” During his service, he saw combat and chased Confederate ships across the Atlantic Ocean to Europe. In a span of five days, the Cambridge and two other ships were able to capture four blockade runners and chase a fifth to shore.Gould also served on the USS Ohio. While onboard of Ohio, he came down with measles and had to leave the ship to go to the hospital. His time in the hospital, from May to October 1863, is the only time he broke from his habit of writing in his diary. During this time he was visited by one of his maternal cousins, Jones, who was the child of emancipated slaves who moved north for fear of being re-enslaved.In October 1863, after he was recovered, Gould was transferred to the USS Niagra. The ship was in port in Gloucester, Massachusetts, waiting for a full complement of men. On December 10, it unexpectedly left port and raced up the eastern seaboard to Nova Scotia chasing after the Chesapeake. The Chesapeake had been captured off the coast of Cape Cod by Confederate sympathizers from the Maritime Provinces.From June 1, 1864, until well into 1865, Gould and the Niagra sailed to and around Europe, searching for Confederate ships. The Niagra was involved in two major confrontations while in Europe, including the taking of the CSS Georgia. It stalked the CSS Stonewall along the coasts of Spain and Portugal but declined to fight the armored ship and let it get away. It was also on the hunt for the CSS Alabama, the CSS Florida, the CSS Shenandoah, and the Laurel, but they did not find them.While off the coast of Cadiz, Spain, those on board the Niagra learned of the surrender of the Confederate Army. “I heard the Glad Tidings that the Stars and Stripes had been planted over the Capital of the D–d Confederacy by the invincible Grant,” Gould committed to his diary. Not knowing that it signaled the end of the war, the Niagra set sail again, this time searching for Confederate ships in Queenstown, Ireland. The Irish came out in great numbers to see the American warship. Leaving Ireland, the Niagra sailed to Charlestown, Massachusetts, where Gould received an honorable discharge after three years of service in the United States Navy.During his first leave from the ship in the spring of 1863, Gould visited his Mary Moore Jones, his maternal aunt, in Boston, and then his eventual wife, Cornelia Reed, on Nantucket. There were a number of other women that he visited in New York during his leaves as well. Gould had an active social life during her leaves, attending concerts, lectures, and public meetings. During his time in New York, he also met William McLaurin, a future North Carolina state representative.Though black men served alongside white men in the Navy during the Civil War and made up roughly 15% of the Union Navy, Gould experienced racism while serving onboard the USS Cambridge. Black soldiers from a Maryland regiment who had been taken aboard temporarily were “treated shamefully,” Gould said when they were not allowed to eat out of mess pans and were called disparaging names. The incident seemed to be out of the ordinary, suggesting that it was not common while serving.Gould visited Wilmington after the war, perhaps in October 1865, and found it to be largely deserted, very unlike the bustling city he knew before the war. He found it to be an improvement, however, where many of the trappings of the former slave economy had been removed.Gould married in 1865 and spent his first year as a married man working as a plasterer on Nantucket. After living in New Hampshire and in Taunton, Massachusetts for a time, in 1871 the Goulds moved to 303-307 Milton Street in Dedham, Massachusetts. In Dedham, Gould became a building contractor and pillar of the community. Gould “took great pride in his work” as a plasterer and brick mason. His skill was rewarded with contracts for public buildings, including several schools.He helped to build the new St. Mary’s Church in his adopted hometown of Dedham. While working on the church, one of his employees improperly mixed the plaster. Even though it was not visible by looking at it and though the defect would not be discovered for some time, Gould insisted that it be removed and reapplied correctly. The decision nearly bankrupted him, but it helped cement his reputation in the town. He also worked as a stonemason, constructing buildings around Dedham.He later took the minutes of the Hancock Mutual Relief Association.Shortly before he got sick with the measles, Gould met John Robert Bond, another black sailor serving on the Ohio. The Gould home was close to the border with Readville, where Bond settled after the war. The two would reconnect ten years after the war and become good friends. Gould would later serve as godfather to Bond’s second son.Gould helped to build the Episcopal Church of the Good Shepard in Oakdale Square, though as a parishioner and not as a contractor. He and his wife were baptized and confirmed there in 1878 and 1879.As a signer of the Articles of Incorporation, he was one of its founders. Gould’s family remained active members of the church and, along with the Bonds and one other family, the Chesnuts were the only black parishioners. There was only one other black family in Dedham at the time. Gould and his family were more likely to experience subtle slights on account of their race as opposed to outright racism while living in Dedham.Gould was extremely active in the Charles W. Carroll Post 144 of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). He “held virtually every position that it was possible to hold in the GAR from the time he joined [in 1882] until his death in 1923, including the highest post, commander, in 1900 and 1901.” He attended the statewide encampments of the GAR in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with Bond and other black veterans from the area. He also joined the Mt. Moriah Masonic Prince Hall Lodge in Cambridge with several other black veterans. In 1911, Gould was interviewed by the local veteran’s association about his wartime experiences.By 1886, Gould would earn enough esteem in the community to be appointed to the General Staff and to lead the parade held in honor of Dedham’s 250th anniversary. Gould gave a speech at Dedham’s 1918 Decoration Day celebrations at which he received “an ovation welcome.” He also regularly spoke to school children on Memorial Day and presided over the town’s celebrations of the holiday. Gould was driven through town on parade days into the 1920s in cars adorned with red, white, and blue decorations.Gould was a committed Republican, as were his children. He adamantly opposed the notion that newly emancipated blacks should be repatriated to Africa or Haiti, saying they had been born under the American flag and would know no other.After he was discharged from the Navy on September 29, 1865, at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Massachusetts, Gould considered moving back to North Carolina where he believed he would have “a fair chance of success [in] my business”. Instead, he immediately went to Nantucket where he married Cornelia Williams Read, on November 22, 1865, at the African Baptist Church on Nantucket. Rev. James E. Crawford, Read’s uncle, officiated. Gould had known Read since childhood, and she was his most frequent wartime correspondent. Cornelia, who had been purchased out of slavery, was then living on Nantucket.Their oldest daughter, Medora Williams, was born on Nantucket, and their oldest son, William B. Gould Jr., was born in Taunton. The rest, Fredrick Crawford, Luetta Ball, Lawrence Wheeler, Herbert Richardson, and twins James Edward and Ernest Moore, were all born in Dedham.The 1880 United States census lists a boy with the last name of Mabson living with the Goulds and working as an employee of Goulds. The child is almost certainly the son of one of Gould’s nephews through his sister Eliza, George Lawrence Mabson or William Mabson.Five of his sons would fight in World War I and one in the Spanish–American War. A photo of the six sons and their father, all in military uniform, would appear in the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, in December 1917. The three youngest sons, all officers, were training to go and fight in World War I in France. Gould’s great-grandson would describe them as “a family of fighters.”It is unknown where Gould learned to read and write as it was illegal to teach those skills to slaves. However, it is clear that he was educated and able to express himself elegantly. In his diary, Gould quoted Shakespeare, had some knowledge of French, and knew a handful of Spanish expressions. It is possible that he was educated in the Front Street Methodist Church near Nixon’s slave quarters, or at St. John’s Episcopal Church.During stops in New York while in the Navy, Gould frequently visited the offices of The Anglo-African, an abolitionist newspaper. Gould raised funds for the publication, become an avid reader, and serve as a correspondent under the nom de plume “Oley.” While onboard the Niagra, Gould often corresponded with Robert Hamilton, the publisher.During the war, Gould sent and received a large number of letters. None of them survive, but each is noted in his diary. They include family, friends, former shipmates, other contraband, and acquaintances in North Carolina, New York, Massachusetts. He corresponds frequently with George W. Price who escaped with him, and with Abraham Galloway, both of whom served in the North Carolina General Assembly after the war. He most frequently writes to his eventual wife, Cornelia Reed, and they exchange at least 60 letters during the war. Cornelia attended school after she moved to Nantucket; it is unclear whether she knew how to read and write prior.Beginning with his time on the Cambridge and continuing through his discharge at the end of the war, Gould kept a diary of his day-to-day activities. According to John Hope Franklin, Gould’s diary is one of three known diaries in existence written during the Civil War by former slaves, and the only one by a Union sailor. It is a “wealth of information about what it was like to be an African-American in the Union Navy.”The diary begins on September 27, 1862, five days after boarding the Cambridge, and runs until his discharge on September 29, 1865. There is a section missing, which included the dates of September 1863 to February 1864. It consists of two books plus 40 unbound pages. It is thought that some sections of the diary, which would cover late 1864 and early 1865, have been destroyed.In the diary, Gould chronicles his trips to the northeastern United States, the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, Portugal, and England. The diary is distinguished not only by its details and eloquent tone, but also by its author’s reflections on the conduct of the war, his own military engagements, race, race relations in the Navy, and what African Americans might expect after the war and during the Reconstruction Era.Gould died on May 25, 1923, at the age of 85, and was interred at Brookdale Cemetery in Dedham. The Dedham Transcript reported his death under the headline “East Dedham Mourns Faithful Soldier and Always Loyal Citizen: Death Came Very Suddenly to William B. Gould, Veteran of the Civil War.”Gould’s diary was discovered 35 years after his death, in 1958, when his attic was being cleaned out. His grandson, William B. Gould III, showed it to his son, William B. Gould IV. At the time, they had known that Gould served in the Navy during the Civil War, but not if he had been enslaved or free prior to his service.Gould IV began researching his ancestor’s life, a process that would last more than 50 years. While teaching at Harvard in the 1970s, Gould IV researched his namesake’s life in nearby Dedham. When he served as the chairman of the National Labor Relations Board under President Bill Clinton in the 1990s, he searched the National Archives. It was only in 1989 that Gould IV discovered his ancestor had been enslaved prior to the war. Gould IV found a notation in the log of the Cambridge that noted Gould had been picked up as contraband and listed the name of his enslaver.Gould IV went on to edit his great-grandfather’s diary and publish it as a book titled Diary of a Contraband: The Civil War Passage of a Black Sailor. He donated the original diary to the Massachusetts Historical Society in 2006.The forward to the published edition was written by the United States, Senator Mark O. Hatfield. According to Hatfield, Gould’s “outstanding life, in Dedham, Massachusetts, following the war, exemplifies American citizenship at its best–citizenship that burned brightly because our nation transcended the inhumanity of slavery.”Gould’s diary was featured in the July 3, 2001, edition of Nightline. In 2020, the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts donated copies of the book to local schools and libraries.On November 9, 2020, the Town of Dedham renamed a 1.3-acre park the William B. Gould Memorial Park. A committee was established to erect a memorial to him on the site. A pew at the Church of the Good Shepherd is dedicated to Gould and Cornelia. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!