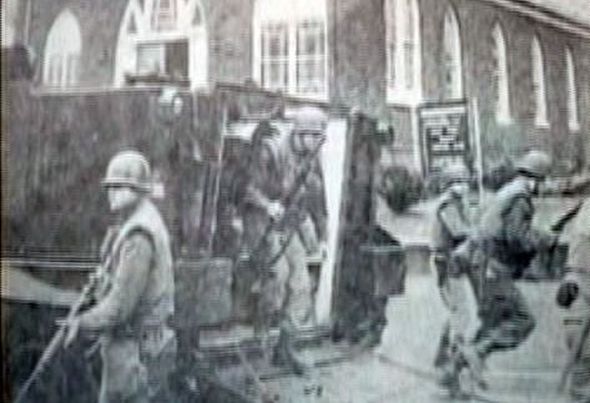

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event, were nine young men and a woman who were wrongfully convicted in 1971 in Wilmington, North Carolina, of arson and conspiracy. Most were sentenced to 29 years in prison, and all ten served nearly a decade in jail before an appeal won their release. The case became an international cause célèbre, in which many critics of the city and state characterized the activists as political prisoners. Amnesty International took up the case in 1976 and provided legal defense counsel to appeal the convictions. In 1978, Governor Jim Hunt reduced the sentences of the ten defendants. In Chavis v. State of North Carolina, 637 F.2d 213 (4th Cir., 1980), the convictions were overturned by the federal appeals court on the grounds that the prosecutor and the trial judge had both violated the defendants’ constitutional rights. They were not retried. In 2012, the Wilmington Ten, including four who had already died, were pardoned by Governor Bev Perdue.Today in our History – December 31, 2012 – The Willington Ten were pardoned.In the 1960s and 1970s, black residents of Wilmington, North Carolina were dissatisfied with the lack of progress in implementing integration and other civil rights reforms achieved by the American Civil Rights Movement through congressional passage of civil rights legislation in 1964 and 1965.Many struggled with poverty and lack of opportunity. Despair at the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. increased racial tensions, with a rise in violence, including the arson of several white-owned businesses.Tension increased further after the 1969 racial integration of Wilmington high schools. The city chose to close the black Williston Industrial High School, a source of community pride. It laid off black teachers, principals, and coaches, transferring students among white-majority schools.Several clashes between white and black students resulted in a number of arrests and expulsions.In response to tensions, members of a Ku Klux Klan chapter and other white supremacist groups began patrolling the streets. They hung an effigy of the white superintendent of the schools and cut his phone lines. Street violence broke out between them and black men. Students decided to boycott the high schools in January 1971. In February, the United Church of Christ sent then-23-year-old Benjamin Chavis, from their Commission for Racial Justice, to Wilmington to try to calm the situation and work with the students. Chavis, who had once worked as an assistant to King, preached non-violence and met with students regularly at Gregory Congregational Church to discuss black history, as well as to organize the boycott.On February 6, 1971, Mike’s Grocery, a white-owned business, was firebombed. Firefighters responding to the fire said they were shot at by snipers from the roof of the nearby Gregory Congregational Church. Chavis and several students had been meeting at the church, which also held other people. The neighborhood erupted in rioting that lasted through the next day, in which two people died.The North Carolina governor called up the North Carolina National Guard, whose forces entered the church on February 8 and removed the suspects. The Guard claimed to have found ammunition in the building. The violence resulted in two deaths, six injuries, and more than $500,000 (equivalent to $3.2 million in 2019) in property damage.Chavis and nine others, eight young black men who were high school students, and an older, white, female anti-poverty worker, were arrested on charges of arson related to the grocery fire. Based on testimony of two black men, they were tried and convicted in state court of arson and conspiracy in connection with the firebombing of Mike’s Grocery.The “Ten” and their sentences:• Benjamin Chavis (age 24) – 34 years• Connie Tindall (age 21) – 31 years• Marvin “Chilly” Patrick (age 19) – 29 years• Wayne Moore (age 19) – 29 years• Reginald Epps (age 18) – 28 years• Jerry Jacobs (age 19) – 29 years• James “Bun” McKoy (age 19) – 29 years• Willie Earl Vereen (age 18) – 29 years• William “Joe” Wright, Jr. (age 19) – 29 years• Ann Shepard (age 35) – 15 yearsAt the time, the state’s case against the Wilmington Ten was seen as controversial both in the state of North Carolina and in the United States. One witness testified that he was given a minibike in exchange for his testimony against the group. Another witness, Allen Hall, had a history of mental illness and had to be removed from the courthouse after recanting on the stand under cross examination.Each of the ten defendants was convicted of the charges. The men’s sentences ranged from 29 years to 34 years for arson, considered severe punishment for a fire in which no one died. Ann Shepard of Auburn, New York, age 35, received 15 years as an accessory before the fact and conspiracy to assault emergency personnel. The youngest of the group, Earl Vereen, was 18 years old at the time of his sentencing. Reverend Chavis was the oldest of the men at age 24.Several national magazines, including Time, Newsweek, Sepia and The New York Times Magazine, published articles in the late 1970s on the trial and its aftermath. When then President Jimmy Carter admonished the Soviet Union in 1978 for holding political prisoners, the Soviets cited the Wilmington Ten as an example of American political imprisonment.Amnesty International took on the Wilmington Ten case in 1976. They classified the eight men still in prison as among 11 black men incarcerated in the U.S. who were considered to be political prisoners, under the definition in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In 1976 and 1977, three key prosecution witnesses recanted their testimony. In 1977 60 Minutes aired a special about the case, suggesting that the evidence against the Wilmington Ten was fabricated. In 1978, the New York Times reporter Wayne King published an investigatory article; based on testimony of a witness whose anonymity he protected, he said that perhaps the prosecution had framed a guilty man, as his source said that he had committed the crimes at the behest of Chavis. In 1978 Governor Jim Hunt reduced the sentences of the Ten. In Chavis v. State of North Carolina, 637 F.2d 213 (4th Cir. 1980), the federal 4th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the convictions, as it determined that: (1) the prosecutor failed to disclose exculpatory evidence, in violation of the defendants’ due process rights (the Brady disclosure); and (2) the trial judge erred by limiting the cross-examination of key prosecution witnesses about special treatment the witnesses received in connection with their testimony, in violation of the defendants’ Sixth Amendment right to confront the witnesses against them. It ordered a new trial, but the state chose not to prosecute again. Chavis and the other seven prisoners were released.A group called the Wilmington Ten Foundation for Social Justice was established to work to improve conditions in the city.In May 2012, Benjamin Chavis and six surviving members of the group petitioned North Carolina governor Bev Perdue for a pardon. The NAACP supported the pardon, as well as arguing for compensation to be paid to the men and their survivors for their years in jail.On December 22, 2012 The New York Times published an editorial titled, “Pardons for the Wilmington Ten”, that urged Governor Perdue to “finally pardon” the group of civil rights activists.Perdue granted a pardon of innocence for each of the ten on December 31, 2012. The pardon qualified each of the ten to state compensation of $50,000 per year of incarceration. The claims were approved by the North Carolina Industrial Commission and signed off on by the North Carolina Attorney General Roy Cooper’s office in May 2013. Total compensation was $1,113,605: Ben Chavis received $244,470 (equivalent to $268,000 in 2019), Marvin Patrick received $187,984 (equivalent to $206,000 in 2019), with most of the remaining rewards being $175,000 each (equivalent to $192,000 in 2019). As four of the Wilmington Ten were deceased before the December 2012 pardons, their families received no compensation. As of February 2014, a case was pending before the NC Industrial Commission, seeking that compensation be awarded to the families of the four deceased: Jerry Jacobs (d. 1989), Joe Wright (d. 1991), Ann Shepard (d. 2011), and Connie Tindall (d. 2012). Research more about this American Champion event and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

Category: Brandon Hardison

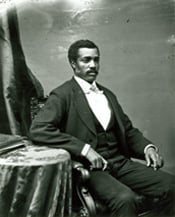

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion fought on both sides of the Civil War, served as Gainesville’s mayor and became Florida’s first black representative.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion fought on both sides of the Civil War, served as Gainesville’s mayor and became Florida’s first black representative. But when he died, few heard of it. Without a word and without a marker.He might be one of the lesser-known black Florida leaders in the state’s history. He was born into slavery in 1842 in Winchester, Virginia. He later became the only person in Alachua County’s history to serve as the Gainesville mayor, a county commissioner, a school board member, a state senator and a U.S. congressman. With that, he laid the groundwork for the Civil Rights era to come a century after him, but many today are surprised to learn he ever existed.Today in our History – December 30, 1842 – Josiah Thomas Walls was born.Overcoming deep political divisions in the Florida Republican Party, Josiah Walls became the first African American to serve his state in Congress. The only black Representative from Florida until the early 1990s, Walls was unseated twice on the recommendation of the House Committee on Elections.When he was not fiercely defending his seat in Congress, Walls fought for internal improvements for Florida. He also advocated compulsory education and economic opportunity for all races: “We demand that our lives, our liberties, and our property shall be protected by the strong arm of our government, that it gives us the same citizenship that it gives to those who it seems would … sink our every hope for peace, prosperity, and happiness into the great sea of oblivion.”Josiah Thomas Walls was born into slavery in Winchester, Virginia, on December 30, 1842. He was suspected to be the son of his master, Dr. John Walls, and maintained contact with him throughout his life. When the Civil War broke out, Walls was forced to be the private servant of a Confederate artilleryman until he was captured by Union soldiers in May 1862. Emancipated by his Union captors, Walls briefly attended the county normal school in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. By July 1863, Josiah Walls was serving in the Union Army as part of the 3rd Infantry Regiment of United States Colored Troops (USCT) based in Philadelphia. His regiment moved to Union–occupied northern Florida in February 1864. The following June, he transferred to the 35th Regiment USCT, where he served as the first sergeant and artillery instructor. While living in Picolota, Florida, Walls met and married Helen Fergueson, with whom he had one daughter, Nellie. He was discharged in October 1865 but decided to stay in Florida, working at a saw mill on the Suwannee River and, later, as a teacher with the Freedmen’s Bureau in Gainesville. By 1868, Walls had saved enough money to buy a 60–acre farm outside the city.One of the few educated black men in Reconstruction–Era Florida, Walls was drawn to political opportunities available after the war. He began his career by representing north–central Florida’s Alachua County in the 1868 Florida constitutional convention. That same year, Walls ran a successful campaign for state assemblyman. The following fall, he was elected to the state senate and took his seat as one of five freedmen in the 24–man chamber in January 1869. Josiah Walls attended the Southern States Convention of Colored Men in 1871 in Columbia, South Carolina.After gaining traction in 1867, the Florida Republican Party disintegrated into factions controlled by scalawags and carpetbaggers—each group fighting for the loyalty of a large constituency of freedmen. The disorganized GOP faced another grim situation when their nominating convention met in August 1870.The three previous years would be remembered as the apex of anti–black violence in the state, orchestrated by the well–organized Jacksonville branches of the Ku Klux Klan. In the face of such unrestrained intimidation, Florida freedmen were widely expected to avoid the polls on Election Day.Fearing conservative Democrats would capture the election in the absence of the black vote, state GOP party leaders—a group made up entirely of white men from the scalawag and carpetbagger factions—agreed that nominating a black man to the state’s lone At–Large seat in the U.S. House of Representatives would renew black voters’ courage and faith in the Republican Party. Passing over the incumbent, former Union soldier Representative Charles Hamilton, the state convention delegates advanced the names of their favorite black candidates. Fierce competition between the nominees led tounruly debate as well as attempts to cast fraudulent votes, and almost resulted in rioting. Walls’s reputation as an independent politician who would not fall under the control of a single faction gave him the edge, and the convention selected him for the party’s nomination on the 11th ballot. The narrow victory was not encouraging for Walls. In the general election, he would confront not only Democratic opposition but also the doubts of his own party.Walls faced former slave owner and Confederate veteran Silas L. Niblack in the general election. Niblack immediately attacked Walls’s capabilities, arguing that a former slave was not educated enough to serve in Congress.Walls countered these charges by challenging his opponent to a debate and speaking at political rallies throughout northern Florida (the most populous section of the state). The campaign was violent; a would–be assassin’s bullet missed Walls by inches at a Gainesville rally, and Election Day was tumultuous. As one Clay County observer noted, Florida had been “turned upside down with politics and the election.” Walls emerged victorious, taking just 627 more votes than Niblack out of the more than 24,000 cast. After presenting his credentials on March 4, 1871, he was immediately sworn in to the 42nd Congress (1871–1873) and given a seat on the Committee on the Militia.Walls feared the cause of public education would languish if it were left to the states. During the 43rd Congress, he enthusiastically supported a measure to establish a national education fund financed by the sale of public land. Walls addressed this issue in his first major floor speech on February 3, 1872: “I believe that the national Government is the guardian of the liberties of all its subjects,” Walls said. “Can [African Americans] protect their liberties without education; and can they be educated under the present condition of society in the States where they were when freed? Can this be done without the aid, assistance, and supervision of the General Government? No, sir, it cannot.” The bill passed with amendments protecting a state’s right to segregated education and granting states greater control over the distribution of federal funds, but the money was never appropriated. Walls’s support for education was further frustrated when the Civil Rights Bill—a battered piece of legislation seeking to eliminate discrimination in public accommodations, first introduced in 1870—came to a vote in February 1875. In November 1876, Walls won a seat in the Florida state senate, where he championed his cause of compulsory public education. Ultimately frustrated by the futility of Republican politics after the collapse of Reconstruction, he took a permanent leave of absence in February 1879.The opportunity to face his old foe Bisbee for the Republican nomination to a Florida U.S. House seat lured him back into politics in 1884. He lost and then ran unsuccessfully in the general election as an Independent candidate. In 1890, Walls lost another bid for the state senate. In 1885, his wife, Helen Fergueson Walls, died and Josiah Walls married her young cousin, Ella Angeline Gass.His successful farm was destroyed when his crops froze in February 1895. Walls subsequently took charge of the farm at Florida Normal College (now Florida A&M University), until his death in Tallahassee on May 15, 1905, interment in the Negro Cemetery. Josiah Walls had fallen into such obscurity, no Florida newspaper published his obituary. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American economist, academic, and political administrator; he served as the first United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (H.U.D.) from 1966 to 1968, when the department was newly established by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American economist, academic, and political administrator; he served as the first United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (H.U.D.) from 1966 to 1968, when the department was newly established by President Lyndon B. Johnson. He was the first African American to be appointed to a US cabinet-level position. Prior to his appointment as cabinet officer, he had served in the administration of President John F. Kennedy. In addition, he had served in New York State government, and in high-level positions in New York City. During the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, he was one of 45 prominent African Americans appointed to positions and helped make up the Black Cabinet, an informal group of African-American public policy advisers.Weaver directed federal programs during the administration of the New Deal, at the same time completing his doctorate in economics in 1934 at Harvard University.Today in our History – December 29, 1907 – Robert Clifton Weaver was born.Robert Clifton Weaver was born on December 29, 1907, into a middle-class family in Washington, D.C. His parents were Mortimer Grover Weaver, a postal worker, and Florence (Freeman) Weaver. They encouraged the boy in his academic studies. His maternal grandfather was Dr. Robert Tanner Freeman, the first African American to graduate from Harvard in dentistry. The young Weaver attended the M Street High School, now known as the Dunbar High School. The high school for blacks at a time of racial segregation had a national reputation for academic excellence. Weaver went on to Harvard University, where he earned a Bachelor of Science and Master of Arts degree. He also earned a Doctor of Philosophy degree in Economics, completing his doctorate in 1934. In 1934, Weaver was appointed as an aide to United States Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes. In 1938, he became special assistant to the US Housing Authority. In 1942, he became administrative assistant to the National Defense Advisory Commission, the War Manpower Commission (1942), and director of Negro Manpower Service. With a reputation for knowledge about housing issues, in 1934 the young Weaver was invited to join President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Black Cabinet. Roosevelt appointed a total of 45 prominent blacks to positions in executive agencies, and called on them as informal advisers on public policy issues related to African Americans, the Great Depression and the New Deal.Weaver drafted the U.S Housing Program under Roosevelt, which was established in 1937. The program was intended to provide financial support to local housing departments, as a subsidy toward lowering the rent poor African Americans had to pay. The program decreased the average rent from $19.47 per month to $16.80 per month. Weaver claimed the scope of this program was insufficient, as there were still many African Americans who made less than the average income. They could not afford to pay for both food and housing. In addition, generally restricted to segregated housing, African Americans could not necessarily take advantage of other subsidized housing.In 1944, Weaver became director of the Commission on Race Relations in the Office of the Mayor of Chicago.In 1945, he became director of community services for the Chicago-based American Council on Race Relations through 1948. In 1949, Weaver become director of fellowship opportunities for the John Hay Whitney Foundation. In 1955, Weaver the first black State Cabinet member in New York when he became New York State Rent Commissioner under Governor W. Averell Harriman. In 1960, he became vice chairman of the New York City Housing and Redevelopment Board.In 1961, Weaver became administrator of the United States Housing and Home Financing Agency (HHFA). After election, Kennedy tried to establish a new cabinet department to deal with urban issues. It was to be called the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Postwar suburban development, following the construction of highways, and economic restructuring had drawn population and jobs from the cities. The nation was faced with a stock of substandard, aged housing in many cities, and problems of unemployment.In 1961, while trying to create HUD, Kennedy had done everything short of promising the new position to Weaver. He appointed him Administrator of the Housing and Home Finance Agency (HHFA), a group of agencies which Kennedy wanted to raise to cabinet status.When Dr. Weaver joined the Kennedy Administration, whose Harvard connections extended to the occupant of the Oval Office, he held more Harvard degrees – three, including a doctorate in economics – than anyone else in the administration’s upper ranks. Some Republicans and southern Democrats opposed the legislation to create the new department. The following year, Kennedy unsuccessfully tried to use his reorganization authority to create the department. As a result, Congress passed legislation prohibiting presidents from using that authority to create a new cabinet department, although the previous Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower administration had created the cabinet-level U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare under that authority.He contributed the compilation housing bill in 1961. He took part in lobbying for the Senior Citizens Housing Act of 1962. In 1965, Congress approved the department. At the time, Weaver was still Administrator of the HHFA. In public, President Lyndon B. Johnson reiterated Weaver’s status as a potential nominee but would not promise him the position. In private, Johnson had strong reservations. He often held pro-and-con discussions with Roy Wilkins, Executive Director of the NAACP.Johnson wanted a strong proponent for the new department. Johnson worried about Weaver’s political sense. Johnson seriously considered other candidates, none of whom was black. He wanted a top administrator, but also someone who was exciting.Johnson was worried about how the new Secretary would interact with congressional representatives from the Solid South; they were overwhelmingly Democrat as most African Americans were still disenfranchised and excluded from the political system. This was expected to change as the federal government enforced civil rights and the provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. As candidates, Johnson considered the politician Richard Daley, mayor of Chicago; and the philanthropist Laurence Rockefeller.Ultimately, Johnson believed that Weaver was the best-qualified administrator. His assistant Bill Moyers had rated Weaver highly on potential effectiveness as the new Secretary. Moyers noted Weaver’s strong accomplishments and ability to create teams. Ten days after receiving the report, the president put forward the nomination, and Weaver was successfully confirmed by the United States Senate.Weaver served as Secretary of United States Department of Housing and Urban Development from 1966 to 1968. Weaver had expressed his concerns about African Americans’ housing issue before 1930 in his article, “Negroes Need Housing”, published by the magazine The Crisis of the NAACP after the Stock Market Crash. He noted there was a great difference between the income of most African Americans and the cost of living; African Americans did not have enough housing supply because of many social factors, including the long economic decline of rural areas in the South. He suggested a government housing program to enable all the African Americans the chance to buy or rent their house.In 1945, Weaver began teaching at Columbia University. In 1969, after serving under President Johnson, Weaver became president of Baruch College. In 1970, Weaver became a distinguished professor of Urban Affairs at Hunter College in New York and taught there until 1978. In 1935, Robert C. Weaver married Ella V. Haith. They adopted a son, who died in 1962.Weavers served on the boards of Metropolitan Life Insurance Company (1969-1978) and Bowery Savings Bank (1969-1980). He served in advisory capacities to the United States Controller General (1973-1997), the New City Conciliation and Appeals Board (1973-1984), Harvard University School of Design (1978-1983), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Legal Defense Fund and NAACP executive board committee (1978-1997). Robert C. Weaver died age 89 on July 17, 1997, in Manhattan, New York. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was Waiting in line to register at her first Continental Congress, she crew stares from some in the throng – “They do when you’re different,” she says.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was Waiting in line to register at her first Continental Congress, she crew stares from some in the throng – “They do when you’re different,” she says. Others came right up and introduced themselves in a gesture of cordiality.”I would think,” says Karen Batchelor Farmer, 26, of Detroit, the first known black member of the 87-year history of the National Society of Daughters of American Revolution, “that they are trying to make me feel at home.”For the Daughters, whose 207,000 members can trace their ancestry back to the Revolutionary War, trying to make Karen Farmer feel “at home” this week is something of a milestone which many Americans once might not have thought possible.Admission of a black to their ranks coupled with an upsurge in youthful members are indicators, be they slight, of the changes in Daughters are undergoing today. One-third of the entire membership is now in the 18-35 age group. But the older members still set the tone for the DAR’s conservative stand on political issues.Daughters of the American Revolution is a very exclusive organization, one that uses a lineage-based membership for its female members. To be eligible for membership, you have to be able to prove that you descend from a person that had ties to the United States’ Independence. Achieving membership is no easy task for some people, and it gets even harder if you have a black lineage. Because of this, DAR was sometimes viewed as a racist organization not out of fact, but out of lack of diversity.Today in our History – December 28, 1977 – Karen Batchelor Farmer is placed in the Daughters of the AMERICAN Revolution. Some of the other requirements once you get past the lineage is that you have to be personally acceptable to society and over 18 years old. The former part is a bit unusual, although there is no record of anyone being turned away for not being personally acceptable. Chapters of DAR exist in all 50 U.S. States and has even found worldwide fame with availabilities in Spain, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and even the United Kingdom. With many other locations on the map, chapters have grown in numbers in the 20th century and now boast over 180,000 members. But back in 1977 on this day of the 28th, they welcomed their first African American member.Karen Batchelor Farmer was admitted after a long genealogical research that started in 1976. It took two years for her to trace her ancestors roots back to William Hood, a patriot who served during the Revolution in the defense of Fort Freeland. Contrary to popular belief, Farmer didn’t reach out to DAR, and it was the other way around. The Ezra Parker Chapter in Michigan contacted Karen and invited her to join the chapter, shattering notions that they were a racist or bigoted organization. This was a huge news story in its day and even made it as a featured story in the New York Times. Along with a couple of interviews and television appearances, this unexpectedly became a big story for its time.Lost in the history is the role that the late James Dent Walker played, the former head of Genealogical Services at the National Archives. With this help, it was made possible, and he also served as the inspiration for Batchelor who co-founded the Fred Hart Williams Genealogical Society in the year of 1979. Karen continues to research her history and is a shining example that black history isn’t always rooted in negative periods like slavery. Research more about this great American Champion and make it a champion day!

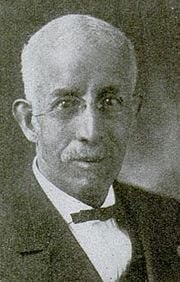

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African-American sociologist who founded the Department of Records and Research at the Tuskegee Institute in 1908.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African-American sociologist who founded the Department of Records and Research at the Tuskegee Institute in 1908.His published works include the Negro Year Book and A Bibliography of the Negro in Africa and America, a bibliography of approximately seventeen thousand references to African Americans.Today in our History – December 26, 1904 – Monroe Nathan Work – Creates The Negro Year Book. Work was born to former slaves in Iredell County, North Carolina, and moved in 1867 to Cairo, Illinois, where his father pursued farming. At the age of 23, Work entered Arkansas City High School (Kansas), an integrated high school in Arkansas City, Kansas. He graduated 3rd in his class, and after undergoing training at the Chicago Theological Seminary, he enrolled in the University of Chicago to become a sociologist. He did research on the correlation between the highest crime rates among blacks and the large proportion living in slums. His paper on the subject would become the first article published in the American Journal of Sociology by an African American. He finished school in Chicago with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Philosophy and a Master of Arts degree in Sociology. After graduating in 1903, Work moved to Savannah, Georgia, to become a professor at Georgia State Industrial College. He married Florence E. Hendrickson of Savannah on December 27, 1904, and they had no children. In July 1905, Work attended the conference of the Niagara Movement at the invitation of W. E. B. Du Bois.In 1908, he accepted a proposal by Booker T. Washington to found the Department of Records and Research at the Tuskegee Institute. While there, he would begin the Negro Year Book, a publication that incorporated his periodic summation of lynching reports, which resulted in the Tuskegee Institute becoming one of the most quoted and undisputed sources on this form of racial violence.According to Work’s biographer, these resources were the largest of their kind in an era when scholarship by and about black Americans was highly inaccessible, and overlooked or ignored by most academics in the US. Work received the Harmon Award in Education in 1928 for his research and involvement in the Negro Year Book and his work on A Bibliography of the Negro in Africa and America.In 1918, he was elected to the American Negro Academy, which was the earliest major African-American learned society.Work died of natural causes in Tuskegee in 1945. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a famous African American sportsman.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a famous African American sportsman. He was known for his professional football career and remarkable performance in 15 seasons of the National Football League.He represented University of Tennessee while playing college football. He was declared NFL Defensive Player of the Year twice.Today in are History – December 26, 2004 – Reggie White dies.Reginald Howard White was born on December 19, 1961 in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He received his early education from Howard High School from where he began playing football. He was trained under Coach Robert Pulliam, a former defensive lineman. In his senior year he made a record of 88 solo tackles and garnered All-American honors. The Knoxville News Sentinel claimed he was rated the number one recruit in Tennessee. Upon graduation, he enrolled in University of Tennessee where he played football for three years. His effective defensive techniques during the games earned him the “Andy Spiva Award”, which is given to most improved defensive player of the year.In 1981, it was recorded that White made 95 tackles and blocked three extra-point attempts. During his game against Memphis State, he had 10 tackles and two sacks which earned him the team’s “outstanding defensive player” title.Moreover, he was named “Southeast Lineman of the Week”, after his performance and win in the game against Georgia Tech. In the 1981 Garden State Bowl, he made eight tackles against Wisconsin and received another title for “Best Defensive Player”. After his ankle injury during the 1982 season, his performance dropped off. However, he maintained his reputation of best defensive player and led the team with seven sacks.Subsequent to losing a game to Iowa with 28-22, Reggie White made up his mind to polish his skills. His determination paid off in the 1983 season when he had 100 tackles and record-breaking 15 sacks. In the 1983 Florida Citrus Bowl, his team defeated Maryland with 30-23 score. In the second quarter of the game he sacked heralded Maryland quarterback Boomer Esiason. His spectacular performance rendered him the All-American, SEC Player of the Year. In fact, he became the finalist of a Lombardi Award. While playing at University of Tennessee, he registered 293 tackles, four fumble recoveries and 32 sacks in total which became remained a record for his school till 2013.Upon his graduation from the University of Tennessee, White signed with the United States Football League’s Memphis Showboats. He played for them for two seasons and scored 198 tackles, seven forced fumbles and 23.5 sacks. In 1985, when the Football League collapsed the Philadelphia Eagles brought him onboard. He remained with the Philadelphia Eagles for eight season playing for the National Football League. In a single season, he made a record of registering 21 sacks and became the only player ever to gain 20 sacks in just 12 games. With his outstanding performance, White raised Eagle’s rank among other National Football league’s teams. One of the sports channel credited him with being the greatest player in the history of Eagles’ franchise.After his tenure with the Eagles, White became a free agent during early 1990s. The Green Bay Packers signed him and he played for six seasons with them. Once again, he brought victories for his team and helped them to win two Super Bowls and Super Bowl XXXI titles.He was received the NFL Defensive Player of the Year award, in 1998. Reggie White died on December 26, 2004, in North Carolina at the age of 43. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African-American newspaper publisher based in Baltimore, Maryland.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African-American newspaper publisher based in Baltimore, Maryland. Born into slavery, he is best known as the founder of the Baltimore Afro-American (also known colloquially/for short as The AFRO), published by the AFRO-American Newspaper Company of Baltimore, Inc. This newspaper is one of the oldest operating black family-owned newspapers in the U.S.AToday in our History – December 25, 1940 – John Henry Murphy Sr. was born.John Henry Murphy was born into slavery in Baltimore, Maryland on Christmas Day 1840. His parents were Benjamin Murphy III, who was a whitewasher, and his wife Susan Colby (or Coby).He is believed to have been enslaved until age 24, when he mustered into the newly organized United States Colored Troops, 30th Infantry Regiment forming in Camp Stanton, Maryland, in February 1864.He eventually served as a non-commissioned officer, reaching the rank of sergeant. (Only whites were allowed to be commissioned officers at the time.)Little is known about young Murphy before his service in the American Civil War. He was among the more than 8,000 Black Marylanders and other states’ residents who mustered into various Black regiments throughout the State of Maryland, after 1863 and emancipation, when the Federal Government decided to accept black recruits in the Army.President Abraham Lincoln announced the “Emancipation Proclamation” in September 1862, giving freedom to all slaves still held within then rebelling Confederate States, and taking effect on New Year’s Day, January 1, 1863. Afterward, the U.S. War Department and state militia officials actively recruited freedmen, free men of color, and fugitive slaves into the Union Army in the U.S.C.T., to serve along with the previous recruited units of various Northern states, such as the famous 54th Massachusetts Regiment.In 1868, Murphy married Martha Elizabeth Howard, a daughter of the well-to-do African-American farmer, Enoch George Howard of Montgomery County, Maryland, who was a free man of color before the war. They met in church. Murphy and his wife Martha settled in Baltimore and had 11 children together; 10 of them survived to adulthood. Among them was their son Carl J. Murphy, who began to work formally with his father on the paper in 1918.After the war, Murphy returned home and worked as a whitewasher, a trade he learned from his father. The development of wallpaper at prices available to the middle class made whitewashing obsolete. Murphy was appointed to the federal civil service in the postal service. He later worked in various jobs: as a porter, janitor, manager of a feed store, and manager of the printing department of the Afro-American, published by Rev. Harry Bragg Sr. for his church.During these years, Murphy became active with Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, founded in Philadelphia in the early 19th century as the first black denomination in the United States. After being appointed as a District Sunday School Superintendent, Murphy used a manual printing press to produce a weekly church publication, the Sunday School Helper, to make copies of materials for students. In 1897 Murphy purchased the printing presses of the Afro-American at auction with $200 borrowed from his wife, who had sold land inherited from her father. He merged the Sunday School Helper with the Afro. In 1900, he acquired another newspaper, The Ledger, and renamed his paper as The Afro-American Ledger. Murphy helped build the African-American community in Baltimore by sharing its news, pressing for civil rights, and reporting on abuses. At first his family worked unpaid for the paper. Later he had up to 100 employees. “He crusaded for racial justice while exposing racism in education, jobs, housing, and public accommodations. In 1913, he was elected president of the National Negro Press Association.” Due to the economic and political power of blacks in Baltimore, who comprised a large community, and the activism of people like Murphy, the Maryland state legislature did not follow the example of other southern states and disenfranchise black voters at the turn of the century. African Americans struggled with discrimination in the city but maintained more freedom and political power than blacks in most other southern states.His son Carl Murphy, by then having a doctorate from the University of Jena in Germany and serving as head of the German department at Howard University, returned to Baltimore in 1918 to work on the paper in his father’s last years. In 1922, after his father’s death, Carl J. Murphy was named as editor and publisher of the paper.After John Henry Murphy’s death on April 5, 1922, his descendants led the newspaper over the course of the next generations, including son Carl J. Murphy for 45 years, and John’s grandson and namesake, John H. Murphy, III. 2008, Murphy was named posthumously to the Hall of Fame, Maryland-Delaware-DC Press Association, established in 1947, research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African-American author and biographer.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African-American author and biographer. She documented slavery in the United States through a collection of interviews with ex-slaves in her book The House of Bondage, or Charlotte Brooks and Other Slaves, which was posthumously published in 1890.Today in our History – December 24, 1853 – Octavia Victoria Rogers Albert was born.She was born Octavia Victoria Rogers in Oglethorpe, Georgia, where she lived in slavery until the emancipation. She attended Atlanta University where she studied to be a teacher. Octavia Rogers saw teaching as a form of worship and Christian service. She received her first teaching job in Montezuma, Georgia.In 1874, at around 21 years old, she married another teacher, Dr. Aristide Elphonso Peter Albert, and they had one daughter together, Laura T. Albert. In 1875 Octavia converted to the African Methodist Episcopal Church, a church under the ministry of Henry McNeal Turner, a Congressman and prominent political activist. After her conversion, she then taught because she saw teaching as a form of worship and as a part of her Christian service like her fellow contemporaries. While teaching in Montezuma, Georgia, both she and her husband became strong advocates for education and “American religion” as they used their home to teach reading and writing lessons. Her husband became an ordained minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1877. Shortly after the couple married, they moved to Houma, Louisiana.In Houma, Louisiana, Octavia Albert began conducting interviews with men and women who were once enslaved. She met Charlotte Brooks for the first time in 1879 and decided to interview her later, along with other former slaves from Louisiana. These interviews were the raw material for her collection of narratives. Although most of the book focuses on the narrative of Charlotte Brooks, Albert also implemented the interviews from ex-slaves John Goodwin, Lorendo Goodwin, Lizzie Beaufort, Colonel Douglass Wilson, and a woman known as Hattie. Their interviews and experiences shaped her book The House of Bondage, or Charlotte Brooks and Other Slaves as a mix of slave stories that would expose the inhumanity of slavery and its effects on individuals. Albert’s goal in writing her book was to tell the stories of slaves, their freedom, and adjustment into a changing society in order to “correct and create history.” The stories of Charlotte Brooks and the others would eventually be compiled into a book after Octavia’s death, published in New York by Hunt and Eaton in 1890. Octavia Albert died on August 19, 1889, before The House of Bondage became widely known. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

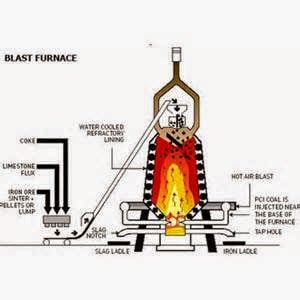

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American inventor known for her patent for a gas furnace.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American inventor known for her patent for a gas furnace.Today in our History – December 23, 1919 – Alice H. Parker patients the gas furnace.Little is known about Alice H. Parkers life, with most of the information coming from Howard University records of her attendance and her patent. Parker was born in Morristown, New Jersey where she lived most of her life. She attended Howard University, in which she graduated with honors in 1910, and Howard University.Growing up in Morristown, New Jersey, the ineffectiveness of her fireplace in the cold New Jersey winters were said to have inspired her to make a better heating solution.Parker’s heating system used independently controlled burner units that drew in cold air and conveyed the heat through a heat exchanger. This air was then fed into individual ducts to control the amount of heat in different areas. It drew in Parker’s patent for heating furnace was filed in 1919. She received patent No. US132590A on December 23, 1919.At the time of filing, most were heating with either coal or wood, but Parker used gas instead. It was not the first gas patent but was the first to contain individually controlled air ducts to transfer heat to different parts of the building. While never implemented due to safety concerns over the regulation of heat flow, it was a precursor to modern heating systems.With her idea for a furnace used with modifications to eliminate safety concerns, it inspired and led the way to features such as thermostats, zone heating and forced air furnaces, common features of modern central heating. Not only that, but by using gas it heated homes much more efficiently then the wood or coal counterparts.While safety was a concern over the regulation of heat flow, it did eliminate the dangers of leaving a fireplace running through the night in order to keep the house heated.Her filing of the patent preceded both the Civil Rights Movement and the Women’s Liberation Movement which makes it especially impressive, as these removed many barriers for black women of her generation.Parker and her patent is mentioned in Black women in America: an historical encyclopedia.In 2019, the National Society of Black Physicists honored Parker as an “African American inventor famous for her patented system of central heating using natural gas.” It called her invention a “revolutionary idea” for the 1920s, “that conserved energy and paved the way for the central heating systems”.The New Jersey Chamber of Commerce established the Alice H. Parker Women Leaders in Innovation Awards to honor women who “talent, hard work and ‘outside-the-box’ thinking to create economic opportunities and help make New Jersey a better place to live and work.”Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African-American sociologist, historian and writer.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African-American sociologist, historian and writer. He is noted for his work on African civilizations prior to encounters with Europeans; his major work is The Destruction of Black Civilization (1971/1974). Williams remains a key figure in the Afrocentrist discourse. He asserted the validity of the discredited Black Egyptian hypothesis and that Ancient Egypt was predominantly a black civilization.Today in our History – December 22, 1898 – Dr. Chancellor James Williams (1898-1992) was born.Of the recent towering figures in the struggle to completely eradicate the pervasive racial myths clinging to the origins of Nile Valley Civilization, few scholars have had the impact of Dr. Chancellor James Williams (1898-1992). Chancellor Williams, the youngest of five children, was born in Bennetsville, South Carolina December 22, 1898. His father had been a slave; his mother a cook, nurse, and evangelist. A stirring writer, Chancellor Williams achieved wide acclaim as the author of the 1971 publication, The Destruction of Black Civilization—Great Issues of a Race from 4500 B.C. to 2000 A.D.Totally uncompromising, highly controversial, broadly sweeping in its range and immensely powerful in its scope, there have been few books published during the past half-century focusing on the African presence in antiquity that have so profoundly affected the consciousness of African people in search of their historical identity. Dr. John Henrik Clarke, now an ancestor and a contemporary of Dr. Williams and one of our most outstanding scholars, described The Destruction of Black Civilization as “a foundation and new approach to the history of our race.” In The Destruction of Black Civilization Chancellor Williams successfully “shifted the main focus from the history of Arabs and Europeans in Africa to the Africans themselves–a history of the Blacks that is a history of Blacks.”The career of Chancellor Williams was spacious and varied; university professor, novelist, and author-historian. He was the father of fourteen children. Blind and in poor health, the last years of Dr. Williams’ life were spent in a nursing home in Washington, D.C.His contributions to the reconstruction of African civilization, however, stand as monuments and beacons reflecting the past, present and future of African people. Chancellor Williams began field research in African History in Ghana (University College) in 1956. His primary focus was on African achievements and autonomous civilizations before Asian and European influences. His last study in 1964 covered an astounding 26 countries and more than 100 language groups. His best known work is “The Destruction of Black Civilization: Great Issues of a Race from 4500 B.C. to 2000 A.D.” For this effort, Dr. Williams was accorded honors by the Black Academy of Arts and Letters.A little known fact about Dr. Williams is that in addition to being an historian and professor, Dr. Williams was president of a baking company, editor of a newsletter, The New Challenge, an economist, high school teacher and principal and a novelist.Dr. Williams remained a staunch advocate that African historians do independent research and investigations so that the history of African people be told and understood from their perspective. Dr. Williams stated clearly, “As long as we rely on white historians to write Black History for us, we should keep silent about what they produce.” Dr. Chancellor Williams joined the Ancestors in 1992. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!