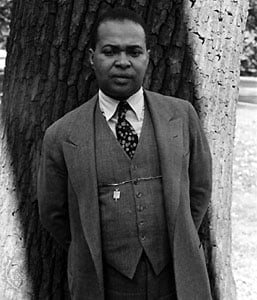

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American poet, novelist, children’s writer, and playwright, particularly well known during the Harlem Renaissance.Today in our History – January 9, 1946 – Countee Cullen (born Countee LeRoy Porter; May 30, 1903 – January 9, 1946) died.Countee Cullen, a poet who rose to fame during the Harlem Renaissance, was a contemporary of famed writer Zora Neale Hurston. Cullen amassed an impressive body of work in a short period of time, moving to becoming a teacher for the latter part of his career. Cullen died on this day in New York in 1946 at the young age of 42.The details of Cullen’s early life are murky, with many scholars agreeing he was born around May 30, 1903. His place of birth has also been a mystery, with claims that he was either born in Lexington, Ky.; New York; or Baltimore, Md. It appears, however, that Cullen claimed New York as his place of birth, which is where he also found his footing as a writer and poet.As a teenager, Cullen came under the care of Reverend Frederick A. Cullen, the pastor of Salem Methodist Episcopal Church; Rev. Cullen would later lead the Harlem chapter of the NAACP. Influenced by the happenings around him, Cullen excelled in high school and entered in to New York University after graduating in 1922.Honing his writing and speaking abilities in high school, Cullen found notoriety at NYU after winning the Witter Byner undergraduate poetry contest in 1923, which was sponsored by the Poetry Society of America. Coming in at second place, Cullen would continue to pen works that were published nationally in a series of poetry publications. In 1925, Cullen won the Witter Byner first place prize, the same year he eventually entered in to Harvard University.Race formed the theme of Cullen’s first published work, “Colors,” and was released while he pursued his Master’s degree in English. The book featured two of Cullen’s most-notable poems in “Heritage” and “Incident.”After graduating from Harvard in 1926, Cullen’s professional career began. It was a turbulent time for Cullen, who worked furiously on a series of poetry collections while editing the popular Caroling Dusk collection as well. In 1928, he received a Guggenheim to write poetry in France and then married Nina Yolande DuBois, the daughter of W. E. B. DuBois. After 1930, Cullen’s work as a poet began to shrink and he focused instead on teaching French and English at New York’s Fredrick Douglass Junior High School. Cullen still wrote, penning his only novel, “One Way To Heaven,” which was published in 1932. Cullen wrote and translated works for the theater and also released a pair of written works for young readers. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

Tag: Brandon hardison

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American educator, missionary and a lifelong advocate for female higher education.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American educator, missionary and a lifelong advocate for female higher education.Today in our History – January 8, 1837 – Fanny Jackson Coppin (January 8, 1837 – January 21, 1913) was born.Born into slavery, Fanny/Fannie Jackson’s freedom was purchased by her aunt at age 12. Fanny Jackson spent the rest of her youth in New Bedford, Massachusetts working as a servant for author George Henry Calvert, studying at every opportunity.On December 21, 1881, Fanny married Reverend Levi Jenkins Coppin, a minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church pastor of Bethel AME Church Baltimore. Fanny Jackson Coppin started to become very involved with her husband’s missionary work, and in 1902 the couple went to South Africa and performed a variety of missionary work, including the founding of the Bethel Institute, a missionary school with self-help programs. After almost a decade of missionary work, Fanny Jackson Coppin’s declining health forced her to return to Philadelphia, and she died on January 21, 1913. Throughout her youth, she used her earnings from her servant work to hire a tutor who guided her studies for three hours a week. With the help of a scholarship from the African Methodist Church and financial support from her aunt, Coppin was able to enroll at Oberlin College, Ohio – the first college in the United States to accept both black and female students – in 1860. Initially enrolling for the “ladies’ course”, Coppin switched to the more rigorous “gentlemen’s course” the following year. She wrote about this experience in her autobiography:”The faculty did not forbid a woman to take the gentleman’s course, but they did not advise it. There was plenty of Latin and Greek in it, and as much mathematics as one could shoulder. Now, I took a long breath and prepared for a delightful contest. All went smoothly until I was in the junior year in College. Then, one day, the Faculty sent for me–ominous request–and I was not slow in obeying it. It was a custom in Oberlin that forty students from the junior and senior classes were employed to teach the preparatory classes. As it was now time for the juniors to begin their work, the Faculty informed me that it was their purpose to give me a class, but I was to distinctly understand that if the pupils rebelled against my teaching, they did not intend to force it. Fortunately for my training at the normal school, and my own dear love of teaching, tho there was a little surprise on the faces of some when they came into the class, and saw the teacher, there were no signs of rebellion.The class went on increasing in numbers until it had to be divided, and I was given both divisions. One of the divisions ran up again, but the Faculty decided that I had as much as I could do, and it would not allow me to take any more work.” She also recalled the pressure she felt under as a black woman: “I never rose to recite in my classes at Oberlin but I felt that I had the honor of the whole African race upon my shoulders. I felt that, should I fail, it would be ascribed to the fact that I was colored. At one time, when I had quite a signal triumph in Greek, the Professor of Greek concluded to visit the class in mathematics and see how we were getting along. I was particularly anxious to show him that I was as safe in mathematics as in Greek. I, indeed, was more anxious, for I had always heard that my race was good in the languages, but stumbled when they came to mathematics.Now, I was always fond of a demonstration, and happened to get in the examination the very proposition that I was well acquainted with; and so went that day out of the class with flying colors.” During her years as a student at Oberlin College, she taught an evening course for free African Americans in reading and writing, and she graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in 1865, becoming one of only three black women to have done so by this time (the others were Mary Jane Patterson and Frances Josephine Norris). Jackson Coppin was the first black teacher at the Oberlin Academy. In 1865, she accepted a position at Philadelphia’s Institute for Colored Youth (now Cheyney University of Pennsylvania). She served as the principal of the Ladies Department and taught Greek, Latin, and Mathematics. In 1869, Jackson Coppin was appointed as the principal of the Institute after the departure of Ebenezer Bassett, becoming the first African American woman to become a school principal. In her 37 years at the Institute, Fanny Jackson was responsible for vast educational improvements in Philadelphia. During her years as principal, she was promoted by the board of education to superintendent.She was the first African American superintendent of a school district in the United States, but soon went back to being a school principal. In 1893, Coppin was one of five African American women invited to speak at the World’s Congress of Representative Women in Chicago, with Anna Julia Cooper, Sarah Jane Woodson Early, Fannie Barrier Williams, and Hallie Quinn Brown, where she delivered a speech entitled “The intellectual progress of the coloured women of the United States since the Emancipation Proclamation”.In 1888, with a committee of women from Mother Bethel, she opened a home for destitute young women after other charities refused them admission.In 1899, the Fannie Jackson Coppin Club was named in her honor for community oriented African American women in Alameda County. This club played an important role in the California suffrage movement. In 1926, a Baltimore teacher training school was named the Fanny Jackson Coppin Normal School (now Coppin State University). To illustrate her point on Black economic independence, Jackson organized an effort to save The Christian Recorder from bankruptcy in 1879.Jackson Coppin’s Reminiscences of a School Life and Hints on Teaching – a combination of autobiography and an account of her teaching and administration at the ICY – was published in 1913. Jackson was politically active her entire life and frequently spoke at political rallies. She was one of the first vice presidents of the National Association of Colored Women, an early advocacy organization for black women founded by Rosetta Douglas. Research more anout this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is a former United States Air Force pilot, military engineer, test pilot, and NASA astronaut as well as former NASA Deputy Administrator.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is a former United States Air Force pilot, military engineer, test pilot, and NASA astronaut as well as former NASA Deputy Administrator. He also served briefly as NASA Acting Administrator in early 2005, covering the period between the departure of Sean O’Keefe and the swearing in of Michael Griffin.Today in our History – January 7, 1941 – Frederick Drew Gregory (born January 7, 1941) was born.Frederick Gregory was born on January 7, 1941, in Washington, D.C.. His father was Francis A. Gregory, an educator who was assistant superintendent for D.C. Public Schools as well as the first black president of the D.C. Public Library Board of Trustees.His father was given the honors of having the Francis A. Gregory Neighborhood Library named after him. His mother was Nora Drew Gregory, a lifelong educator as well as public library advocate.She was also the sister of noted African-American physician, surgeon and researcher Dr. Charles Drew, who developed improved techniques for blood storage, and applied his expert knowledge in developing large-scale blood banks early in World War II, saving thousands of Allied lives. Gregory’s great-grandfather was educator James Monroe Gregory. His family lore suggests he has an ancestor from Madagascar. Gregory was raised in Washington, D.C. and graduated from Anacostia High School. He attended the United States Air Force Academy after being nominated by Adam Clayton Powell Jr.; there, he received his Air Force commission and an undergraduate degree in military engineering.After graduating from the Air Force Academy, Gregory earned his wings after helicopter school, flew in Vietnam, transitioned to fighter aircraft, attended the Navy Test Pilot School, and then conducted testing as an engineering test pilot for both the Air Force and NASA. He also received a master’s degree in information systems from George Washington University.During his time in the Air Force, Gregory logged approximately 7,000 hours in more than 50 types of aircraft as a helicopter, fighter and test pilot. He flew 550 combat rescue missions in Vietnam.Gregory was selected as an astronaut in January 1978. His technical assignments included: Astronaut Office representative at the Kennedy Space Center during initial Orbiter checkout and launch support for STS-1 and STS-2; Flight Data File Manager; lead spacecraft communicator (CAPCOM); Chief, Operational Safety, NASA Headquarters, Washington, D.C.; Chief, Astronaut Training; and a member of the Orbiter Configuration Control Board and the Space Shuttle Program Control Board. Notably, he was one of the CAPCOM during the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster.A veteran of three Shuttle missions he has logged about 456 hours in space. He served as pilot on STS-51B (April 29 to May 6, 1985), and was the spacecraft commander on STS-33 (November 22–27, 1989), and STS-44 (November 24 to December 1, 1991).Gregory served at NASA Headquarters as Associate Administrator for the Office of Safety and Mission Assurance (1992–2001), and was Associate Administrator for the Office of Space Flight (2001–2002). On August 12, 2002 Mr. Gregory was sworn in as NASA Deputy Administrator. In that role, he was responsible to the Administrator for providing overall leadership, planning, and policy direction for the Agency.The Deputy Administrator performs the duties and exercises the powers delegated by the Administrator, assists the Administrator in making final Agency decisions, and acts for the Administrator in his or her absence by performing all necessary functions to govern NASA operations and exercise the powers vested in the Agency by law. The Deputy Administrator articulates the Agency’s vision and represents NASA to the Executive Office of the President, Congress, heads of Federal and other appropriate Government agencies, international organizations, and external organizations and communities. From the departure of Sean O’Keefe on February 20, 2005, to the swearing in of Michael D. Griffin on April 14, 2005, he was the NASA Acting Administrator. He returned to the post of Deputy Administrator and on September 9, 2005, submitted his resignation. He was replaced on November 29, 2005, by Shana Dale.Gregory was married to the former Barbara Archer of Washington, D.C. until her death in 2008. They had two grown children. Frederick, D. Jr., a Civil Servant working in the office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (DOD), and a graduate of Stanford University and the University of Florida.Heather Lynn is a social worker and graduate of Sweet Briar College and the University of Maryland. He is now married to the former Annette Becke of Washington, D.C. and together they have three children and six grandchildren. His recreational interests include reading, boating, hiking, diving, biking and traveling. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

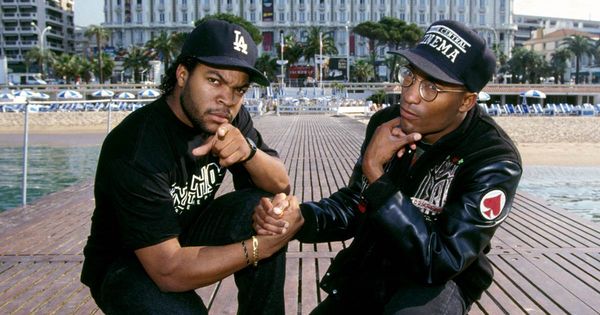

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American film director, screenwriter, producer, and actor.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American film director, screenwriter, producer, and actor. He was best known for writing and directing Boyz n the Hood (1991), for which he was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director, becoming, at age 24, the first African American and youngest person to have ever been nominated for that award. He was a native of South Los Angeles, and many of his films, such as Poetic Justice (1993), Higher Learning (1995), and Baby Boy (2001), had themes which resonated with the contemporary urban population. He also directed the drama Rosewood (1997) and the action films Shaft (2000), 2 Fast 2 Furious (2003), and Four Brothers (2005). He co-created the television crime drama Snowfall. He was nominated for the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Directing for a Limited Series, Movie, or Dramatic Special for “The Race Card”, the fifth episode of The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story.Today in our History – January 6, 1968 – John Daniel Singleton (January 6, 1968 – April 28, 2019) was born.Singleton was raised near the violence-ridden south-central section of Los Angeles. While studying screenwriting at the University of Southern California, he won several writing awards, which led to his signing a contract with the Creative Artists Agency well before his 1990 graduation. As a student, Singleton wrote a coming-of-age screenplay— titled Boyz n the Hood—that chronicled the lives of three childhood friends growing up in the south-central area amid poverty and gang violence. It was filmed by Columbia Pictures and starred Cuba Gooding, Jr., Laurence Fishburne, and rapper-turned-actor Ice Cube. The film received widespread critical acclaim, rapidly accumulating accolades and awards. Singleton was nominated for Academy Awards for best screenplay and best director, making him the first African American to be nominated for the best director honor.He followed up this success by directing pop superstar Michael Jackson in the music video for “Remember the Time” (1992). His next film, Poetic Justice (1993), starred Jackson’s sister, singer Janet Jackson. Singleton’s other films included Higher Learning (1995), a drama investigating a variety of social issues as it follows the lives of three college freshmen (1993); Rosewood (1997), based on a true story of racial violence in Florida in the 1920s; a remake of the landmark blaxploitation film Shaft (2000); the action film 2 Fast 2 Furious (2003); and Four Brothers (2005), starring Mark Wahlberg and Tyrese Gibson.In the 2010s Singleton began working in television, and he directed episodes of such shows as Empire, The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story, and Billions. He co-created Snowfall (2017– ), which centers on the crack epidemic in 1980s Los Angeles. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion organization is a historically African American Greek-lettered fraternity.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion organization is a historically African American Greek-lettered fraternity. Since the fraternity’s founding on January 5, 1911 at Indiana University Bloomington, the fraternity has never restricted membership on the basis of color, creed or national origin.The fraternity has over 160,000 members with 721 undergraduate and alumni chapters in every state of the United States, and international chapters in the United Kingdom, Germany, South Korea, Japan, United States Virgin Islands, Nigeria, South Africa, and The Bahamas. The president of the national fraternity is known as the Grand Polemarch, who assigns a Province Polemarch for each of the twelve provinces (regions) of the nation. The fraternity has many notable members recognized as leaders in the arts, athletics, business, Civil Rights, education, government, and science sectors at the local, national and international level.The Kappa Alpha Psi Journal has been the official magazine of the fraternity since 1914. The Journal is published four times a year in February, April, October and December. Frank M. Summers was the magazine’s first editor and later became the Fourteenth Grand Polemarch. The former editor of the magazine was Jonathan Hicks. The current editor of the magazine is Earl T. Tildon.Kappa Alpha Psi sponsors programs providing community service, social welfare and academic scholarship through the Kappa Alpha Psi Foundation and is a supporter of the United Negro College Fund and Habitat for Humanity. Kappa Alpha Psi is a member of the National Pan-Hellenic Council (NPHC) and the North American Interfraternity Conference (NIC). The fraternity is the oldest predominantly African American Greek-letter society founded west of the Appalachian Mountains still in existence, and is known for its “cane stepping” in NPHC organized step shows. Kappa Alpha Psi celebrated its 100th anniversary on January 5, 2011; one of four predominantly African American collegiate fraternities to do so.Today in our History – January 5, 1911 – Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc. (ΚΑΨ) is founded. The founders of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc. are: Elder Watson Diggs, more affectionately known as ‘The Dreamer’, Dr. Ezra D. Alexander, Dr. Byron Kenneth Armstrong, Atty. Henry Tourner Asher, Dr. Marcus Peter Blakemore, Paul Waymond Caine, George Wesley Edmonds, Dr. Guy Levis Grant, Edward Giles Irvin, and Sgt. John Milton Lee.The founders endeavored to establish the fraternity with a strong foundation before embarking on plans of expansion. By the end of the first year, the ritual was completed, and a design for the coat of arms and motto had begun. Frederick Mitchell’s name is on the application for the Incorporation of the Fraternity but withdrew from school and thus never became a member of the Fraternity.The fraternity was founded as Kappa Alpha Nu on the night of January 5, 1911, by ten African-American college students. The decision upon the name Kappa Alpha Nu may have been to honor the Alpha Kappa Nu club which began in 1903 on the Indiana University campus but had too few registrants to effect continued operation. The organization known today as Kappa Alpha Psi was nationally incorporated under the name of Kappa Alpha Nu on May 15, 1911. The name of the organization was changed to its current name in 1915, shortly after its creation.Kappa Alpha Psi initiate Frank Summers was one of eighteen members of the Indiana University Track team awarded the letter “I” in 1915.During this time there were very few African-American students at the majority white campus at Bloomington, Indiana and they were a small minority due to the era of the Jim Crow laws.Many African-American students rarely saw each other on campus and were discouraged or prohibited from attending student functions and extracurricular activities by white college administrators and fellow students. African-American students were denied membership on athletic teams with the exception of track and field. The racial prejudice and discrimination encountered by the founders strengthened their bond of friendship and growing interest in starting a social group. By 1913, the fraternity expanded with the second undergraduate chapter opened at the University of Illinois—Beta chapter; then the University of Iowa—Gamma chapter. After this, Kappa Alpha Psi chartered undergraduate chapters on Black college campuses at Wilberforce University—Delta chapter, and Lincoln University (Pennsylvania)—Epsilon chapter. In 1920, Xi chapter was chartered at Howard University. In 1921, the fraternity installed the Omicron chapter at Columbia University, its first at an Ivy League university. The fraternity’s first chapter in the South was established in 1921 at Morehouse College— Pi chapter. Kappa Alpha Psi expanded through the Midwest, South, and West at both white and black colleges.Some believe the Greek letters Kappa Alpha Nu were chosen as a tribute to Alpha Kappa Nu, but the name became an ethnic slur among racist factions. Founder Elder Watson Diggs, while observing a young initiate compete in a track meet, overheard fans referring to the member as a “kappa alpha nig”, and a campaign to rename the fraternity ensued. The resolution to rename the group was adopted in December 1914, and the fraternity states, “the name acquired a distinctive Greek letter symbol and KAPPA ALPHA PSI thereby became a Greek letter Fraternity in every sense of the designation.” Kappa Alpha Psi has been the official name since April 15, 1915. In 1947, at the Los Angeles Conclave, the National Silhouettes of Kappa Alpha Psi were established as an auxiliary group, which membership comprises wives or widows of fraternity members. In 1980, the Silhouettes were officially recognized and granted a seat on the Board of Directors of the Kappa Alpha Psi Foundation. Silhouettes provide support and assistance for the activities of Kappa Alpha Psi at the Grand chapter, province and local levels.In the 1950s, as black Greek-letter organizations began the tradition of step shows, the fraternity began using the “Kappa Kane” in what it termed “cane stepping”. The kappa canes were longer in the 1950s than in later decades.In the early 1960s, the cane was decorated with the fraternity colors. In the 1970s the cane was shortened so brothers could “twirl” and tap the cane in the choreography with high dexterity. The process of covering the cane in the fraternal colors is considered as ‘wrapping’ and is done very specifically.In the 1960s the national organization did not condone the use of canes or Kappa Alpha Psi’s participation in step shows contending that “the hours spent in step practices by chapters each week would be better devoted to academic or civic achievement.” Senior Grand Vice Polemarch Ullysses McBride complained about the vulgar language and obscene gestures sometimes engaged in by cane-stepping participants during these stepshows. In 1986, during the fraternity’s 66th national meeting, cane stepping was finally recognized as an important staple of Kappa Alpha Psi. Research more about this great American Champion organization and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event begins during the late 1960s, Rep. Charles Diggs (D-Mich.) created the Democracy Select Committee (DSC) in an effort to bring black members of Congress together.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event begins during the late 1960s, Rep. Charles Diggs (D-Mich.) created the Democracy Select Committee (DSC) in an effort to bring black members of Congress together.Diggs noticed that he and other African-American members of Congress often felt isolated because there were very few of them in Congress and wanted to create a forum where they could discuss common political challenges and interests.“The sooner we get organized for group action, the more effective we can become,” Diggs said.The DSC was an informal group that held irregular meetings and had no independent staff or budget but that changed a few years later. As a result of court-ordered redistricting, one of several victories of the Civil Rights Movement, the number of African-American members of Congress rose from nine to 13, the largest ever at the time, and members of the DSC decided at the beginning of the 92nd Congress (1971-1973) that a more formal group was needed.Today in our History – January 4, 1971 – The Congressional Black Caucus organized.Since its establishment in 1971, the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) has been committed to using the full Constitutional power, statutory authority, and financial resources of the federal government to ensure that African Americans and other marginalized communities in the United States have the opportunity to achieve the American Dream. As part of this commitment, the CBC has fought for the past 48 years to empower these citizens and address their legislative concerns by pursuing a policy agenda that includes but is not limited to the following: • reforming the criminal justice system and eliminating barriers to reentry;• combatting voter suppression;• expanding access to world-class education from pre-k through post-secondary level;• expanding access to quality, affordable health care and eliminating racial health disparities;• expanding access to 21st century technologies, including broadband;• strengthening protections for workers and expanding access to full, fairly-compensated employment;• expanding access to capital, contracts, and counseling for minority-owned businesses; and• promoting U.S. foreign policy initiatives in Africa and other countries that are consistent with the fundamental right of human dignity.For the 116th Congress, the CBC has a historic 55 members of the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate, representing more than 82 million Americans, 25.3 percent of the total U.S. population, and more than 17 million African-Americans, 41 percent of the total U.S. African-American population.In addition, the CBC represents almost a fourth of the House Democratic Caucus. The CBC is engaged at the highest levels of Congress with members who serve in House leadership. Representative James E. Clyburn (D-SC) serves as the Majority Whip in the House of Representatives, Representative Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY) serves as Chairman of the House Democratic Caucus and Representative Barbara Lee (D-CA) serves as co-chair of the House Democratic Steering and Policy Committee. In addition, five CBC members serve as chairs on full House committees, and 28 CBC members serve as chairs on House subcommittees.While the CBC has predominately been made up of members of the Democratic Party, the founding members of the caucus envisioned a non-partisan organization. Consequently, the CBC has a long history of bipartisan collaboration and members who are both Democrat and Republican.As founding member Rep. William L. Clay, Sr. said when the CBC was established, “Black people have no permanent friends, no permanent enemies…just permanent interests.” Research more about this American Champion organization and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event was according to a letter by the tobacco planter John Rolfe, the widower of Pocahontas, a ship landed in England’s 12-year-old Jamestown settlement and “brought not anything but 20, and odd, Negroes, which the Governor and the Cape Merchant bought for victuals – provisions.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event was according to a letter by the tobacco planter John Rolfe, the widower of Pocahontas, a ship landed in England’s 12-year-old Jamestown settlement and “brought not anything but 20, and odd, Negroes, which the Governor and the Cape Merchant bought for victuals – provisions.The “20 and odd’’ already had been through hell. They were taken prisoner of war in what is now Angola by African mercenaries working with the Portuguese; marched to the Atlantic coast, where they were branded, penned, forcibly baptized; and finally chained head-to-foot below deck on a Spanish ship headed for Mexico and a life of slavery. The San Juan Bautista carried about 350 enslaved people, more than a third of whom died on the crossing. Then, in the Gulf of Mexico, the ship was attacked by two English privateers – pirates under a foreign flag of convenience. The two ships carried about 60 of the Africans north toward Virginia.Virginia had no law to permit or ban slavery. But the Africans became slaves in fact, if not law. In 1624, two of them, identified as Anthony and Isabella, were listed in the household of Capt. William Tucker, a military commander and settler.The following year, the two appear again in a census, this time along with “William theire Child Baptised.’’ Another African child, unnamed, also appears for the first time in the same 1625 census. But William is the first identified by name.Today in our History – January 3, 1821 – The first African American was born, William Tucker.A family that traces its bloodline to America’s first enslaved Africans said Friday that their ancestors endured unimaginable toil and hardship — but they also helped forge the nation.“Four hundred years ago, our family started building America, can I get an Amen?” Wanda Tucker said before a crowd in the Tucker Family Cemetery in Hampton, Virginia.“They loved,” she continued. “They experienced loss. They worked. They created. They made a way out of no way, determined that their labor would not be in vain.”Tucker, a college professor in Arizona, spoke at one of several events in Virginia this weekend that will mark the arrival of more than 30 enslaved Africans at a spot on the Chesapeake Bay in August 1619.The men and women who came from what is now Angola arrived on two ships and were traded for food and supplies from English colonists. The landing is considered a pivotal moment in American history, setting the stage for a system of race-based slavery that continues to haunt the nation.Many of the first Africans are known today by only their first names. They included Antony and Isabella, who became servants for a Captain William Tucker.They had a son named William Tucker who many believe was the first documented African child born in English-occupied North America.“We’re still here,” Tucker shouted in her family’s shaded cemetery, which included many worn gravestones, as well as white crosses where ground penetrating radar had recently found unmarked graves.The Africans came just 12 years after the founding of Jamestown, England’s first permanent colony, and weeks after the first English-style legislature was convened there.American slavery and democratic self-rule were born almost simultaneously in 1619. But the commemoration of the Africans’ arrival comes at a time of growing debate over American identity and mounting racial tension.During his remarks, Virginia Lt. Gov. Justin Fairfax rebuked President Donald Trump’s racist tweets. One had called on four Democratic congresswomen of color to “go back” to their home countries, even though three were born in the U.S.“You do not tell us to go back to where we came from,” said Fairfax, who is black. “We built where you came from.”Fairfax, who is facing allegations of sexual assault from two women, said he met Trump in July when they marked the 400th anniversary of the legislature in Jamestown.“The president had to bow down to the descendant of an enslaved African,” Fairfax said.People at the ceremony also said the Tucker family’s story symbolizes those of all African Americans.“I think our family history is like some many other peoples,” said Carolita Jones Cope, 60, before the ceremony. Cope is a retired U.S. Department of Labor attorney who lives in Springfield, Virginia, and is among the descendants.“Our descendants arrived here not by choice but in a bound status,” she said. “But they became landholders, business owners and farmers. And they supported each other through the struggle.”Research more about this great American Champion event and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

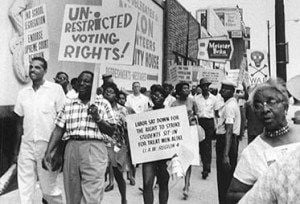

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event forced the American government to act On 6 August 1965 President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law, calling the day “a triumph for freedom as huge as any victory that has ever been won on any battlefield” (Johnson, “Remarks in the Capitol Rotunda”).

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event forced the American government to act On 6 August 1965 President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law, calling the day “a triumph for freedom as huge as any victory that has ever been won on any battlefield” (Johnson, “Remarks in the Capitol Rotunda”). The law came seven months after Martin Luther King launched a Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) campaign based in Selma, Alabama, with the aim of pressuring Congress to pass such legislation.“In Selma,” King wrote, “we see a classic pattern of disenfranchisement typical of the Southern Black Belt areas where Negroes are in the majority” (King, “Selma—The Shame and the Promise”).In addition to facing arbitrary literacy tests and poll taxes, African Americans in Selma and other southern towns were intimidated, harassed, and assaulted when they sought to register to vote. Civil rights activists met with fierce resistance to their campaign, which attracted national attention on 7 March 1965, when civil rights workers were brutally attacked by white law enforcement officers on a march from Selma to Montgomery.Today in our History – January 2, 1965 – A voter registration drive, led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. started in Selma, Alabama.The 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibited discrimination in employment and public accommodations. But many African Americans were denied an equally fundamental constitutional right, the right to vote.The most effective barriers to black voting were state laws requiring prospective voters to read and interpret sections of the state constitution. In Alabama, voters had to provide written answers to a 20-page test on the Constitution and state and local government. Questions included: Where do presidential electors cast ballots for president? Name the rights a person has after he has been indicted by a grand jury?In an effort to bring the issue of voting rights to national attention, Martin Luther King, Jr. launched a voter registration drive in Selma, Alabama, in early 1965. Even though blacks slightly outnumbered whites in the city of 29,500 people, Selma’s voting rolls were 99 percent white and 1 percent black.For seven weeks, King led hundreds of Selma’s black residents to the county courthouse to register to vote. Nearly 2,000 black demonstrators, including King, were jailed by County Sheriff James Clark for contempt of court, juvenile delinquency, and parading without a permit.After a federal court ordered Clark not to interfere with orderly registration, the sheriff forced black applicants to stand in line for up to five hours before being permitted to take a “literacy” test. Not a single black voter was added to the registration rolls.When a young black man was murdered in nearby Marion, King responded by calling for a march from Selma to the state capitol of Montgomery, 50 miles away. On March 7, 1965, black voting-rights demonstrators prepared to march. “I can’t promise you that it won’t get you beaten,” King told them, “… but we must stand up for what is right!”As they crossed a bridge spanning the Alabama River, 200 state police with tear gas, night sticks, and whips attacked them. The march resumed on March 21 with federal protection. The marchers chanted: “Segregation’s got to fall … you never can jail us all.” On March 25 a crowd of 25,000 gathered at the state capitol to celebrate the march’s completion. Martin Luther King, Jr. addressed the crowd and called for an end to segregated schools, poverty, and voting discrimination. “I know you are asking today, ‘How long will it take?’ … How long? Not long, because no lie can live forever.”Within hours of the march’s end, four Ku Klux Klan members shot and killed a 39-year-old white civil rights volunteer from Detroit named Viola Liuzzo. President Johnson expressed the nation’s shock and anger.”Mrs. Liuzzo went to Alabama to serve the struggle for justice,” the President said. “She was murdered by the enemies of justice who for decades have used the rope and the gun and the tar and the feather to terrorize their neighbors.”Two measures adopted in 1965 helped safeguard the voting rights of black Americans. On January 23, the states completed ratification of the 24th Amendment to the Constitution barring a poll tax in federal elections. At the time, five Southern states still had a poll tax. On August 6, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act, which prohibited literacy tests and sent federal examiners to seven Southern states to register black voters. Within a year, 450,000 Southern blacks registered to vote. Research more about the great American Champion event and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

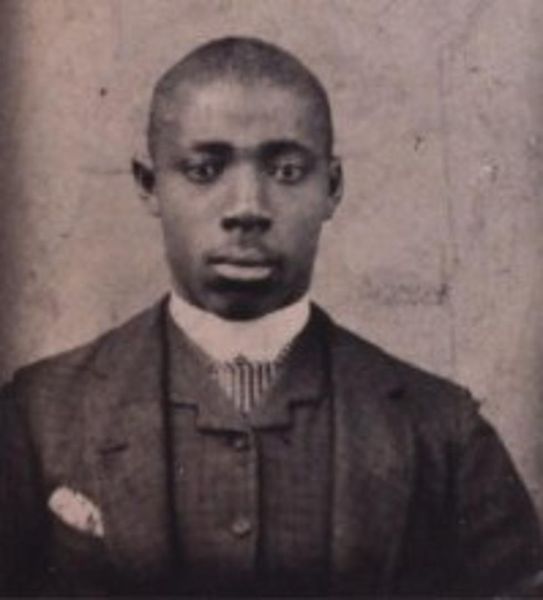

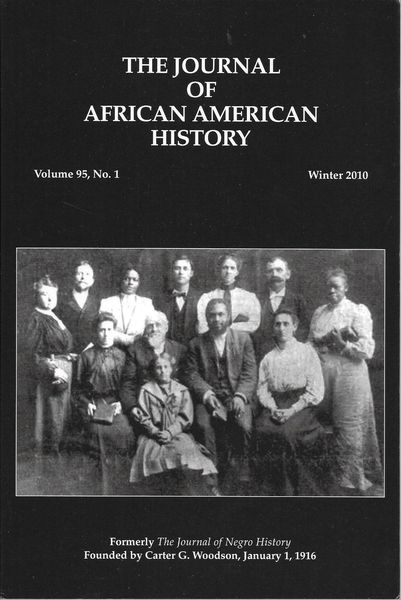

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event is a quarterly academic journal covering African-American life and history.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event is a quarterly academic journal covering African-American life and history. It was founded in 1916 by Carter G. Woodson.The journal is owned and overseen by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) and was established in 1916 by Woodson and Jesse E. Moorland. The journal publishes original scholarly articles on all aspects of the African-American experience. The journal annually publishes more than sixty (60) reviews of recently published books in the fields of African and African-American life and history. As of 2018, the Journal is published by the University of Chicago Press on behalf of the ASALH.Today in our History – January 1, 1916 – The Journal of African American History, formerly The Journal of Negro History.The Journal of African American History (formally the Journal of Negro History) was one of the first scholarly texts or journals to cover African-American history. It was founded in January 1916 by Carter G. Woodson, an African-American historian and journalist. The journal was and is a publication of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, an organization founded by Woodson. The journal was the dominant source to learn about African American history at the time of its conception, because there were no other such texts. The journal gave black scholars the chance to publish articles examining African-American history and culture while also documenting the current black experience in the United States. While the journal mainly published the work of black authors and encouraged their academic success, it was also an outlet for white scholars who had different views than their counterparts. Woodson’s efforts to cover African-American history at a time where it was unacknowledged has led him to receive the nickname “Father of African American History.” Carter G. Woodson (1875–1950) was a professor and historian at Howard University. He was among the first black scholars, such as other notable figures like W. E. B. Du Bois, to receive a doctoral degree.So, naturally was a pioneer in the field of black history and African American studies. After getting his Ph.D. in history from Harvard University, he joined the faculty at Howard University.During his time of the study, there was really no such thing as black history. Woodson was one of the first black scholars to identify this need and do something about it. On the creation of The Journal of Negro History, Carol Adams, the CEO of the Chicago Museum of African American History, commented: “He didn’t just see a need, he moved to fill the need,” Adams says. “It wasn’t easy to get your work published if you were an African-American scholar, for example, so he started a journal and then a press.” In 1915, Woodson co-founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH). This organization’s name was changed to, much like the Journal of Negro History’s rechristening to the Journal of African American history, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (also abbreviated as ASALH). This non-profit organization, founded in Chicago and based in Washington, D.C. This organization, along with Woodson, was responsible for the creation of African American History week in 1926, choosing the week that coincided with the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln to bring attention to the importance of black history. African American history week built upon the work of the Journal of Negro History, as is celebrated the need to examine the history and celebrate African-American culture.The journal is published by the (ASALH) Association for the Study of African American Life and History. Woodson’s work establishing the Journal of Negro History and African American History week were the early roots of what we now know as Black History Month.Black History Month is every year in February, still covering the week of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln’s birthdays that was originally chosen by Woodson.Since its conception in 1926, the Journal of African American History has featured and published the work of several notable scholars over the years. These include famous names such as Benjamin Quarles, John Hope Franklin, and W. E. B. Du Bois.To name a few other couple of notable figures who were on record as adding to the history of African Americans, Jesse Moorland is the first to come to mind. Moorland on record was a key contributor along with Woodson himself for beginning black history month. Moorland contributed to what is now known as one of the world’s largest libraries on African-American history through considerable donations of personal novels and manuscripts along with activist Arthur Spingarn. Both of whom are remembered through the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University.To add to the list of notable figures, Joe R. Feagin comes to mind. Joe is currently the president of the American Sociological Association, he completed research on issues with racism in society who contributed as well to the history of African Americans originally started by Carter Woodson, the father of African-American history. The Journal of African American History played a vital role for women of color in the 1900s. Before it was commonplace for women to be openly welcomed in the world of academia, the Journal of African American History (still known then as The Journal of Negro History) provided women of color with an outlet to publish their work without the ridicule of others. The first black female historians paved their way using the Journal of Negro History. Female authors contributed nine percent of the articles published in the Journal of Negro History, compared to an average of only three percent in other notable journals of the time, such as Mississippi Valley Historical Review or the Journal of Southern History. The Journal of Negro History was therefore quite revolutionary in its time by allowing more female authors to contribute to the journal. One of the most notable examples includes Marion Thompson Wright, the first black female to receive a doctoral degree in history. She published her own work on blacks in New Jersey in the Journal of Negro History. The Journal of African American History is owned by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. In 2018, the editor V. P. Franklin, who began working for his alma mater, Harvard University along with Harvard’s Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, a well-known historian in African-American studies decided to sign a deal with the University of Chicago Press to have it publish the journal on behalf of the ASLAH. Pero. G. Dagbovie is an acclaimed history professor at Michigan State University focused primarily on black history, black women’s history, and Black Power. He is also a well known author of countless books including African American History Reconsidered and the biography of Carter G. Woodson, the founder of The Journal of African American History. Because of Dagbovie’s work and his unique background on African-American history, he has been appointed as the next editor of the Journal, replacing V.P Franklin. As mentioned above, The Journal of African American History was essential for starting the effort to document and fill the need for the study of black history. However, it also gave black scholars opportunities to challenge the status quo, fight stereotypes, and attempt to create a more favorable perception of African Americans.It also gave people of color the chance to publish their works and be recognized in the academic field. It really encouraged and fostered the academic success of black Americans, especially black historians. Research more about this American Champion event and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event, were nine young men and a woman who were wrongfully convicted in 1971 in Wilmington, North Carolina, of arson and conspiracy.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event, were nine young men and a woman who were wrongfully convicted in 1971 in Wilmington, North Carolina, of arson and conspiracy. Most were sentenced to 29 years in prison, and all ten served nearly a decade in jail before an appeal won their release. The case became an international cause célèbre, in which many critics of the city and state characterized the activists as political prisoners. Amnesty International took up the case in 1976 and provided legal defense counsel to appeal the convictions. In 1978, Governor Jim Hunt reduced the sentences of the ten defendants. In Chavis v. State of North Carolina, 637 F.2d 213 (4th Cir., 1980), the convictions were overturned by the federal appeals court on the grounds that the prosecutor and the trial judge had both violated the defendants’ constitutional rights. They were not retried. In 2012, the Wilmington Ten, including four who had already died, were pardoned by Governor Bev Perdue.Today in our History – December 31, 2012 – The Willington Ten were pardoned.In the 1960s and 1970s, black residents of Wilmington, North Carolina were dissatisfied with the lack of progress in implementing integration and other civil rights reforms achieved by the American Civil Rights Movement through congressional passage of civil rights legislation in 1964 and 1965.Many struggled with poverty and lack of opportunity. Despair at the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. increased racial tensions, with a rise in violence, including the arson of several white-owned businesses.Tension increased further after the 1969 racial integration of Wilmington high schools. The city chose to close the black Williston Industrial High School, a source of community pride. It laid off black teachers, principals, and coaches, transferring students among white-majority schools.Several clashes between white and black students resulted in a number of arrests and expulsions.In response to tensions, members of a Ku Klux Klan chapter and other white supremacist groups began patrolling the streets. They hung an effigy of the white superintendent of the schools and cut his phone lines. Street violence broke out between them and black men. Students decided to boycott the high schools in January 1971. In February, the United Church of Christ sent then-23-year-old Benjamin Chavis, from their Commission for Racial Justice, to Wilmington to try to calm the situation and work with the students. Chavis, who had once worked as an assistant to King, preached non-violence and met with students regularly at Gregory Congregational Church to discuss black history, as well as to organize the boycott.On February 6, 1971, Mike’s Grocery, a white-owned business, was firebombed. Firefighters responding to the fire said they were shot at by snipers from the roof of the nearby Gregory Congregational Church. Chavis and several students had been meeting at the church, which also held other people. The neighborhood erupted in rioting that lasted through the next day, in which two people died.The North Carolina governor called up the North Carolina National Guard, whose forces entered the church on February 8 and removed the suspects. The Guard claimed to have found ammunition in the building. The violence resulted in two deaths, six injuries, and more than $500,000 (equivalent to $3.2 million in 2019) in property damage.Chavis and nine others, eight young black men who were high school students, and an older, white, female anti-poverty worker, were arrested on charges of arson related to the grocery fire. Based on testimony of two black men, they were tried and convicted in state court of arson and conspiracy in connection with the firebombing of Mike’s Grocery.The “Ten” and their sentences:• Benjamin Chavis (age 24) – 34 years• Connie Tindall (age 21) – 31 years• Marvin “Chilly” Patrick (age 19) – 29 years• Wayne Moore (age 19) – 29 years• Reginald Epps (age 18) – 28 years• Jerry Jacobs (age 19) – 29 years• James “Bun” McKoy (age 19) – 29 years• Willie Earl Vereen (age 18) – 29 years• William “Joe” Wright, Jr. (age 19) – 29 years• Ann Shepard (age 35) – 15 yearsAt the time, the state’s case against the Wilmington Ten was seen as controversial both in the state of North Carolina and in the United States. One witness testified that he was given a minibike in exchange for his testimony against the group. Another witness, Allen Hall, had a history of mental illness and had to be removed from the courthouse after recanting on the stand under cross examination.Each of the ten defendants was convicted of the charges. The men’s sentences ranged from 29 years to 34 years for arson, considered severe punishment for a fire in which no one died. Ann Shepard of Auburn, New York, age 35, received 15 years as an accessory before the fact and conspiracy to assault emergency personnel. The youngest of the group, Earl Vereen, was 18 years old at the time of his sentencing. Reverend Chavis was the oldest of the men at age 24.Several national magazines, including Time, Newsweek, Sepia and The New York Times Magazine, published articles in the late 1970s on the trial and its aftermath. When then President Jimmy Carter admonished the Soviet Union in 1978 for holding political prisoners, the Soviets cited the Wilmington Ten as an example of American political imprisonment.Amnesty International took on the Wilmington Ten case in 1976. They classified the eight men still in prison as among 11 black men incarcerated in the U.S. who were considered to be political prisoners, under the definition in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In 1976 and 1977, three key prosecution witnesses recanted their testimony. In 1977 60 Minutes aired a special about the case, suggesting that the evidence against the Wilmington Ten was fabricated. In 1978, the New York Times reporter Wayne King published an investigatory article; based on testimony of a witness whose anonymity he protected, he said that perhaps the prosecution had framed a guilty man, as his source said that he had committed the crimes at the behest of Chavis. In 1978 Governor Jim Hunt reduced the sentences of the Ten. In Chavis v. State of North Carolina, 637 F.2d 213 (4th Cir. 1980), the federal 4th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the convictions, as it determined that: (1) the prosecutor failed to disclose exculpatory evidence, in violation of the defendants’ due process rights (the Brady disclosure); and (2) the trial judge erred by limiting the cross-examination of key prosecution witnesses about special treatment the witnesses received in connection with their testimony, in violation of the defendants’ Sixth Amendment right to confront the witnesses against them. It ordered a new trial, but the state chose not to prosecute again. Chavis and the other seven prisoners were released.A group called the Wilmington Ten Foundation for Social Justice was established to work to improve conditions in the city.In May 2012, Benjamin Chavis and six surviving members of the group petitioned North Carolina governor Bev Perdue for a pardon. The NAACP supported the pardon, as well as arguing for compensation to be paid to the men and their survivors for their years in jail.On December 22, 2012 The New York Times published an editorial titled, “Pardons for the Wilmington Ten”, that urged Governor Perdue to “finally pardon” the group of civil rights activists.Perdue granted a pardon of innocence for each of the ten on December 31, 2012. The pardon qualified each of the ten to state compensation of $50,000 per year of incarceration. The claims were approved by the North Carolina Industrial Commission and signed off on by the North Carolina Attorney General Roy Cooper’s office in May 2013. Total compensation was $1,113,605: Ben Chavis received $244,470 (equivalent to $268,000 in 2019), Marvin Patrick received $187,984 (equivalent to $206,000 in 2019), with most of the remaining rewards being $175,000 each (equivalent to $192,000 in 2019). As four of the Wilmington Ten were deceased before the December 2012 pardons, their families received no compensation. As of February 2014, a case was pending before the NC Industrial Commission, seeking that compensation be awarded to the families of the four deceased: Jerry Jacobs (d. 1989), Joe Wright (d. 1991), Ann Shepard (d. 2011), and Connie Tindall (d. 2012). Research more about this American Champion event and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!