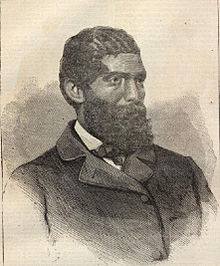

GM – FBF – We are proud to be back in New Jersey for today’s story. He was a public school graduate, teacher and later became a dentist and taught blacks the practice of dentistry. He was abolitionist and became a lawyer and helped assemble the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment during the American War between the States. He became the first African American lawyer to argue a case before the U.S. Supreme Court. Enjoy!

Remember – “I Will Sink or Swim with My Race” – John Swett Rock

Today in our History – John Swett Rock died in Boston on December 3, 1866.

John Swett Rock was born to free black parents in Salem, New Jersey in 1825. He attended public schools in New Jersey until he was 19 and then worked as a teacher between 1844 and 1848. During this period Rock began his medical studies with two white doctors. Although he was initially denied entry, Rock was finally accepted into the American Medical College in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He graduated in 1852 with a medical degree. While in medical school Rock practiced dentistry and taught classes at a night school for African Americans. In 1851 he received a silver medal for the creation of an improved variety of artificial teeth and another for a prize essay on temperance.

At the age of 27, Rock, a teacher, doctor and dentist, moved to Boston, Massachusetts in 1852 to open a medical and dental office. He was commissioned by the Vigilance Committee, an organization of abolitionists, to treat fugitive slaves’ medical needs. During this period Dr. Rock increasingly identified with the abolitionist movement and soon became a prominent speaker for that cause. While he called on the United States government to end slavery, he also urged educated African Americans to use their talents and resources to assist their community.

Following his own advice, Rock studied law and in 1861 became one of the first African Americans to be admitted to the Massachusetts Bar before the Civil War. Soon afterwards Massachusetts Governor John Andrew appointed Rock Justice of the Peace for Boston and Suffolk County. In 1863 Rock helped assemble the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, the first officially-recognized African American unit in the Union Army during the Civil War. Rock would later campaign for equal pay for these and other black soldiers.

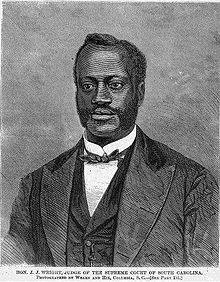

In 1865, with support from Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner,

Rock became the first African American lawyer to argue a case before the U.S.

Supreme Court.

Previously, Rock’s health had deteriorated in the late 1850s. He underwent several

surgeries and was forced to halt his medical practice. Believing he would

receive more advanced care overseas, Rock made plans to sail to France in 1858.

Rock, however, was denied a passport by U.S. Secretary of State Lewis Cass who,

citing the 1857 Dred Scott Decision, claimed Federal passports were evidence of

citizenship and since African Americans we not citizens, Rock could not be

issued a passport.

Outraged abolitionist supporters in Boston persuaded the Massachusetts Legislature to demand the Secretary of State grant Rock a passport. The State Department relented and Rock sailed to France. French surgeons recommended that Rock give up his speaking engagements and his medical practice. Rock agreed but continued his abolitionist activities. Nonetheless his health continued to worsen.

On April 9, 1866 the Civil Rights Act of 1866 was passed which enforced the 13th Amendment. Rock enjoyed this honor for less than a year. He became ill with the common cold that weakened his already failing health, and limited his ability to commute efficiently. On December 3, 1866, John S. Rock died in his mother’s home in Boston of tuberculosis at the age of 41. He was laid to rest in Everett’s Woodlawn Cemetery, and was buried with full Masonic honors. His admittance into the Supreme Court is recorded on his tombstone. Research more about this great American and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!