GM – FBF – Today’s story is about the misinformation that many American’s black and white still have or had about this organizations. I was a benefactor of one of their programs that helped me and my brother by giving us a good meal before we went to school. The U.S. Government could not afford to have many programs during that time that would uplift black communities, so they found ways to infiltrate or ways to discrete the organizations true purpose. Read – Research and understand. Enjoy!

Remember – “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” – Gill Scott -Heron.

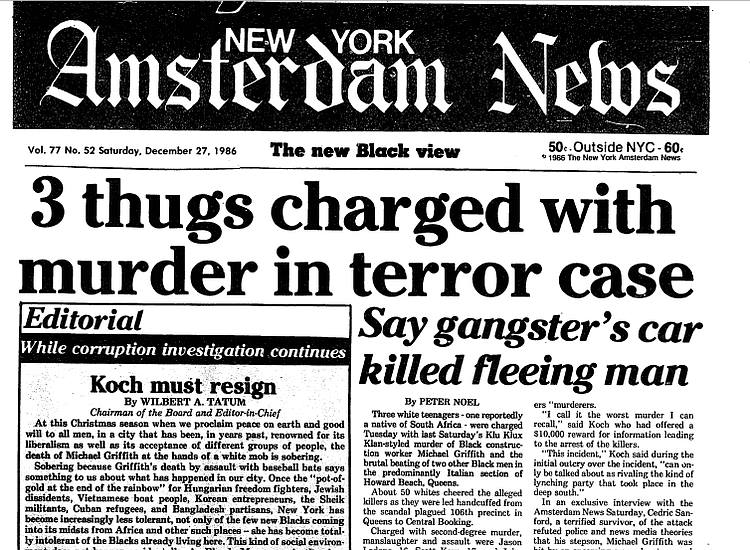

Today in our History – October 10, 1966 – The Black Panther Party (BPP) was given lite to the world.

The Black Panther Party (BPP), originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, was a political organization founded by Bobby Seale and Huey Newton in October 1966. The party was active in the United States from 1966 until 1982, with international chapters operating in the United Kingdom in the early 1970s, and in Algeria from 1969 until 1972.

At its inception on October 10,1966, the Black Panther Party’s core practice was its armed citizens’ patrols to monitor the behavior of officers of the Oakland Police Department and challenge police brutality in Oakland, California. In 1969, community social programs became a core activity of party members. The Black Panther Party instituted a variety of community social programs, most extensively the Free Breakfast for Children Programs, and community health clinics to address issues like food injustice.The party enrolled the largest number of members and made the greatest impact in the Oakland-San Francisco Bay Area, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Philadelphia.

Federal Bureau of Investigation Director J. Edgar Hoover called the party “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country”, and he supervised an extensive counterintelligence program (COINTELPRO) of surveillance, infiltration, perjury, police harassment, and many other tactics designed to undermine Panther leadership, incriminate party members, discredit and criminalize the Party, and drain the organization of resources and manpower. The program was also accused of assassinating Black Panther members.

Black Panther Party members were involved in many fatal firefights with police including Huey Newton allegedly killing officer John Frey in 1967 and the 1968 Eldridge Cleaver led ambush of Oakland police officers which wounded two officers and killed Panther Bobby Hutton. The party was also involved in many internal conflicts including the murders of Alex Rackley and Betty Van Patter.

Government oppression initially contributed to the party’s growth, as killings and arrests of Panthers increased its support among African Americans and on the broad political left, both of whom valued the Panthers as a powerful force opposed to de facto segregation and the military draft. Black Panther Party membership reached a peak in 1970, with offices in 68 cities and thousands of members, then suffered a series of contractions. After being vilified by the mainstream press, public support for the party waned, and the group became more isolated. In-fighting among Party leadership, caused largely by the FBI’s COINTELPRO operation, led to expulsions and defections that decimated the membership.

Popular support for the Party declined further after reports appeared detailing the group’s involvement in illegal activities such as drug dealing and extortion schemes directed against Oakland merchants. By 1972 most Panther activity centered on the national headquarters and a school in Oakland, where the party continued to influence local politics. Though under constant police surveillance, the Chicago chapter remained active and maintained their community programs until 1974. The Seattle chapter lasted longer than most, with a breakfast program and medical clinics that continued even after the chapter disbanded in 1977. Party contractions continued throughout the 1970s, and by 1980, the Black Panther Party had just 27 members.

The history of the Black Panther Party is controversial. Scholars have characterized the Black Panther Party as the most influential black movement organization of the late 1960s, and “the strongest link between the domestic Black Liberation Struggle and global opponents of American imperialism”. Other commentators have described the Party as more criminal than political, characterized by “defiant posturing over substance”.

Ten-Point Program

The Black Panther Party first publicized its original Ten-Point program on May

15,1967, following the Sacramento action, in the second issue of The Black

Panther newspaper. The original ten points of “What We Want Now!”

follow:

We want freedom. We want

power to determine the destiny of our Black Community.

We want full employment for our people.

We want an end to the robbery by the Capitalists of our Black Community.

We want decent housing, fit for shelter of human beings.

We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent

American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our

role in the present day society.

We want all Black men to be exempt from military service.

We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people.

We want freedom for all Black men held in federal, state, county and city

prisons and jails.

We want all Black people when brought to trial to be tried in court by a jury

of their peer group or people from their Black Communities, as defined by the

Constitution of the United States.

We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.Research

more about the BPP and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!