GM – FBF – Toda’s story is about a Black woman who loved to

write children’s books and journalism. She has been all around the globe

signing books and telling her story she loved people and wanted everyone to

enjoy their lives. Enjoy!

Remember – “Having solved one problem, there was always a new one cropping up

to take its place.” – Ann Penty

Today in our History – October 12, 1908 – Ann Penty was born.

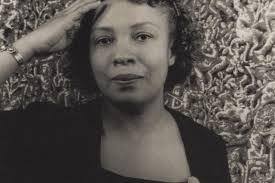

Ann Petry (October 12, 1908 – April 28, 1997) was an American writer of novels, short stories, children’s books and journalism. Her 1946 debut novel The Street became the first novel by an African-American woman to sell more than a million copies.

Ann Lane was born on October 12, 1908, in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, as the youngest of three daughters to Peter Clark Lane and Bertha James Lane. Her parents belonged to the black minority numbering 15 inhabitants of the small town. Her father was a pharmacist and her mother was a shop owner, chiropodist, and hairdresser. Ann was also the niece of Anna Louise James.

Ann and her sister were raised “in the classic New England tradition: a study in efficiency, thrift, and utility (…) They were filled with ambitions that they might not have entertained had they lived in a city along with thousands of poor blacks stuck in demeaning jobs.”

The family had none of the trappings of the middle class until Petry was well into adulthood. Before her mother became a businesswoman, she worked in a factory, and her sisters worked as maids. The Lane girls were raised sheltered from most of the disadvantages other black people in the United States had to experience due to the color of their skin; however there were a number of incidents of racial discrimination.

As Petry wrote in “My Most Humiliating Jim Crow Experience”, published in Negro Digest in 1946, there was an incident where a racist decided that they did not want her on a beach. Her father wrote a letter to The Crisis in 1920 or 1921 complaining about a teacher who refused to teach his daughters and his niece. Another teacher humiliated her by making her read the part of Jupiter, the illiterate ex-slave in the Edgar Allan Poe short story “The Gold-Bug”.

Petry had a strong family foundation with well-traveled uncles, who had many stories to tell her when coming home; her father, who overcame racial obstacles, opened a pharmacy in the small town; and her mother and aunts set a strong example: Petry, interviewed by the Washington Post in 1992, says about her tough female family members that “it never occurred to them that there were things they couldn’t do because they were women.”

Petry’s desire to become a professional writer was raised first in high school when her English teacher read her essay to the class and commented on it with the words: “I honestly believe that you could be a writer if you wanted to.” The decision to become a pharmacist was her family’s. After graduating in 1929 from Old Saybrook High School, she went to college and graduated with a Ph.G. degree from the University of Connecticut College of Pharmacy in New Haven in 1931 and worked in the family business for several years, while also writing short stories. On February 22, 1938, she married George D. Petry of New Iberia, Louisiana, which brought her to New York.

She worked as a journalist writing articles for newspapers including The Amsterdam News (between 1938 and 1941) and The People’s Voice (1941–44), and published short stories in The Crisis, where her first story appeared in 1943, Phylon, and other outlets. Between 1944 and 1946 she studied creative writing at Columbia University. She also worked at an after-school program at P.S. 10 in Harlem. It was during this period that she experience and understood what the majority of the black population of the United States had to go through in their everyday life. Traversing the Harlem streets, living for the first time among large numbers of poor black people, seeing neglected children up close—Petry’s early years in New York inevitably made impressions on her and led her to put her experiences to paper. Her daughter Liz explained to the Post that “her way of dealing with the problem was to write this book [The Street], which maybe was something that people who had grown up in Harlem couldn’t do.”

Petry’s first and most popular novel, The Street, was published in 1946 and won the Houghton Mifflin Literary Fellowship with book sales exceeding one million copies.

Back in Old Saybrook in 1947, Petry worked on Country Place (1947), The Narrows (1953), other stories, and books for children, but they never achieved the same success as her first book. She drew on her personal experiences of the hurricane in Old Saybrook in Country Place. Although the novel is set in the immediate aftermath of World War II, Petry identified the 1938 New England hurricane as the source for the storm that is at the center of her narrative.

Petry was a member of the American Negro Theater and appeared in productions including On Striver’s Row. She also lectured at University of California, Berkeley, Miami University and Suffolk University, and was Visiting Professor of English at the University of Hawaii.

She died in Old Saybrook at the age of 88 on April 28, 1997. She was outlived by her husband George, who died in 2000, and her only daughter, Liz Petry. Research more about Black writers abd share with your babies. Make it a champion day!