GM – FBF – Today’s story is about a Black man who died penniless but was the “Best” in the world at his profession. I should thank the makers of Hennessy; the liquor company for reminding the world that he existed by having an ad campaign recently on television and radio. I did a story on him last year at this time and I try to do someone one you have not heard of or know little about. So, please read about this great talent during a time no one wanted him to be the greatest of all time in his event and will go down as one of the preeminent American sports pioneers of the 20th century. Enjoy

Remember – “I pray they will carry on in spite of that dreadful

monster prejudice, and with patience, courage, fortitude and perseverance

achieve success for themselves.” “Life is too short for any man to hold

bitterness in his heart.” – Marshall Walter “Major” Taylor

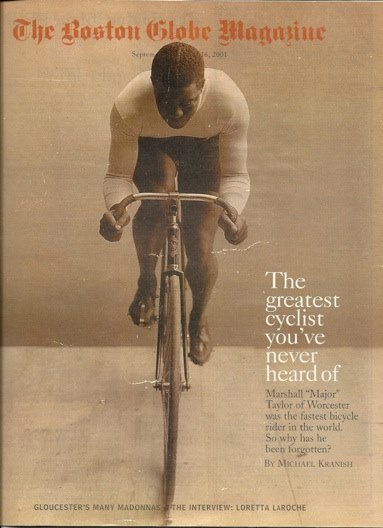

Today in our History – November 26, 1878, Marshall Walter “Major” Taylor is

born, and would go on to be just the second black world champion in any sport.

Indianapolis, Indiana’s

cyclist Marshall Walter “Major” Taylor began racing professionally

when he was 18 years old. By 1900, Taylor held several major world records and

competed in events around the globe. After 14 years of grueling competition and

fending off intense racism, he retired at age 32. He died penniless in Chicago

on June 21, 1932.

Marshall Walter “Major” Taylor was born November 26, 1878, in Indianapolis,

Indiana. In the early years of his life, Taylor was raised without much money.

His father, a farmer and Civil War veteran, worked as carriage driver for a

wealthy white family.

Taylor often joined his dad at work and became close to his father’s employers,

especially their son, who was similar in age. Eventually, Taylor moved in with

the family, a radical change that gave the young boy a more stable home

situation with opportunities for a better education.

Taylor was essentially treated as one of the family’s own, and one of their

early gifts to him was a new bike. Taylor took to it immediately, teaching

himself bike tricks that he showed off to his friends.

When Taylor’s antics caught the attention of a local bike shop owner, he was

hired to exhibit his tricks outside the shop to attract more customers. Often,

he donned a military uniform, which earned him the nickname “Major” from the

shop’s clientele. The nickname remained with him for the rest of his

life.

With the encouragement of the bike shop owner, Taylor entered his first bike

race when he was in his early teens, a 10-mile event that he won easily. By the

age of 18, Taylor had relocated to Worcester, Massachusetts, and started racing

professionally. In his first competition, an exhausting six-day ride at Madison

Square Garden in New York City, Taylor finished eighth.

From there, he pedaled into history. By 1898, Taylor had captured seven world

records. A year later, he was crowned national and international champion,

making him just the second black world champion athlete, after bantamweight

boxer George Dixon. He collected medals and prize money in races around the

world, including Australia, Europe and all over North America.

As his successes mounted, however, Taylor had to fend off racial insults and

attacks from fellow cyclists and cycling fans. Though black athletes were more

accepted and had less overt racism to contend with in Europe, Taylor was barred

from racing in the American South. Many competitors hassled and bumped him on

the track, and crowds often threw things at him while he was riding. During one

event in Boston, a cyclist named W.E. Becker pushed Taylor off his bike and

choked him until police intervened, leaving Taylor unconscious for 15 minutes.

Despite his fame and talent, Taylor was subject to intense racism and

discrimination. He was barred from races, turned away from restaurants and

hotels, and subjected to racist insults throughout his career. At one point he

was banned from a track in his hometown of Indianapolis after defeating white

cyclists (and breaking two world records in the process).

Exhausted by his grueling racing schedule and the racism that followed him,

Taylor retired from cycling at age 32. In 1910, despite the obstacles, he had

become one of the wealthiest athletes — black or white — of his time.

Sadly, Taylor found his post-racing life to be more difficult. Business

ventures failed, and he wound up losing much of his earnings. He also became

estranged from his wife and daughter. For Taylor, a retired black athlete,

there were few options after retirement. There were no speaking engagements or endorsements.

With his health deteriorating and his investments dwindling, Taylor eventually

fell into poverty and faded into obscurity.

Taylor moved to Chicago in 1930, and boarded at a local YMCA as he tried to

sell copies of his self-published autobiography, The Fastest Bicycle Rider in

the World. Taylor died alone and penniless in the charity ward of a Chicago

hospital on June 21, 1932.

Buried in an unmarked grave in the welfare section of Mount Glenwood Cemetery

in Cook County, Illinois, Taylor’s body was exhumed in 1948 through the efforts

of a group of former pro racers and Schwinn Bicycle Company owner Frank

Schwinn, and moved to a more prominent area of the cemetery.

It would be another forty years before Taylor’s accomplishments were more

formally recognized. In the 1980s, Taylor was inducted to the United States

Bicycling Hall of Fame, and Indianapolis built the Major Taylor Velodrome,

naming their new track after the man who had once been banned from it.

More recently, Taylor was posthumously awarded the Korbel Lifetime Achievement

Award by USA Cycling, and the city of Worcester, Massachusetts, Taylor’s

adopted home, erected a statue honoring Taylor outside their library. Marshall

“Major” Taylor was a pioneer black athlete and his incredible

achievements are finally receiving the recognition they deserve.