GM – FBF – “No nation, savage or civilized, save only the

United States of America, has confessed its inability to protect its women save

by hanging, shooting, and burning alleged offenders.” – Ida B. Wells

Remember – “There is nothing we can do about the lynching

now, as we are out-numbered and without arms.” – Ida B. Wells

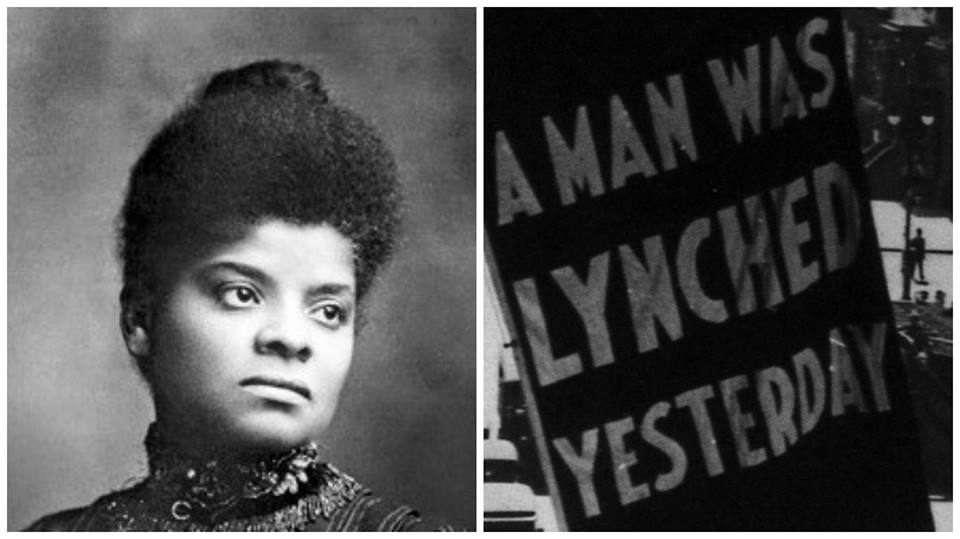

Today in our History – Ida B. Wells-Barnett, known for much of

her public career as Ida B. Wells, was an anti-lynching activist, a muckraking

journalist, a lecturer, and a militant activist for racial justice. She lived

from July 16, 1862 to March 25, 1931.

Born into slavery, Wells-Barnett went to work as a teacher when

she had to support her family after her parents died in an epidemic. She wrote

on racial justice for Memphis newspapers as a reporter and newspaper owner.

She was forced to leave town when a mob attacked her offices in

retaliation for writing against an 1892 lynching.

After briefly living in New York, she moved to Chicago, where

she married and became involved in local racial justice reporting and

organizing. She maintained her militancy and activism throughout her life.

Early Life

Ida B. Wells was enslaved at birth. She was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi,

six months before the Emancipation Proclamation. Her father, James Wells, was a

carpenter who was the son of the man who enslaved him and his mother. Her

mother, Elizabeth, was a cook and was enslaved by the same man as her husband

was. Both kept working for him after emancipation. Her father got involved in

politics and became a trustee of Rust College, a freedman’s school, which Ida

attended.

A yellow fever epidemic orphaned Wells at 16 when her parents

and some of her brothers and sisters died.

To support her surviving brothers and sisters, she became a

teacher for $25 a month, leading the school to believe that she was already 18

in order to obtain the job.

Education and Early Career

In 1880, after seeing her brothers placed as apprentices, she moved with her

two younger sisters to live with a relative in Memphis.

There, she obtained a teaching position at a black school, and

began taking classes at Fisk University in Nashville during summers.

Wells also began writing for the Negro Press Association. She

became editor of a weekly, Evening Star, and then of Living Way, writing under

the pen name Iola. Her articles were reprinted in other black newspapers around

the country.

In 1884, while riding in the ladies’ car on a trip to Nashville,

Wells was forcibly removed from that car and forced into a colored-only car,

even though she had a first class ticket. She sued the railroad, the Chesapeake

and Ohio, and won a settlement of $500. In 1887, the Tennessee Supreme Court

overturned the verdict, and Wells had to pay court costs of $200.

Wells began writing more on racial injustice and she became a

reporter for, and part owner of, Memphis Free Speech. She was particularly

outspoken on issues involving the school system, which still employed her. In

1891, after one particular series, in which she had been particularly critical (including

of a white school board member she alleged was involved in an affair with a

black woman), her teaching contract was not renewed.

Wells increased her efforts in writing, editing, and promoting

the newspaper.

She continued her outspoken criticism of racism. She created a

new stir when she endorsed violence as a means of self-protection and

retaliation.

Lynching in Memphis

Lynching in that time had become one common means by which African Americans

were intimidated. Nationally, in about 200 lynchings each year, about

two-thirds of the victims were black men, but the percentage was much higher in

the South.

In Memphis in 1892, three black businessmen established a new

grocery store, cutting into the business of white-owned businesses nearby.

After increasing harassment, there was an incident where the business owners

fired on some people breaking into the store. The three men were jailed, and

nine self-appointed deputies took them from the jail and lynched them.

Anti-Lynching Crusade

One of the lynched men, Tom Moss, was the father of Ida B.

Wells’ goddaughter, and Wells knew him and his partners to be

upstanding citizens. She used the paper to denounce the lynching, and to

endorse economic retaliation by the black community against white-owned

businesses as well as the segregated public transportation system. She also

promoted the idea that African Americans should leave Memphis for the

newly-opened Oklahoma territory, visiting and writing about Oklahoma in her

paper. She bought herself a pistol for self-defense.

She also wrote against lynching in general. In particular, the

white community became incensed when she published an editorial denouncing the

myth that black men raped white women, and her allusion to the idea that white

women might consent to a relationship with black men was particularly offensive

to the white community.

Wells was out of town when a mob invaded the paper’s offices and

destroyed the presses, responding to a call in a white-owned paper. Wells heard

that her life was threatened if she returned, and so she went to New York,

self-styled as a “journalist in exile.”

Anti-Lynching Journalist in Exile

Ida B. Wells continued writing newspaper articles at New York Age, where she

exchanged the subscription list of Memphis Free Speech for a part ownership in

the paper. She also wrote pamphlets and spoke widely against lynching.

In 1893, Wells went to Great Britain, returning again the next

year. There, she spoke about lynching in America, found significant support for

anti-lynching efforts, and saw the organization of the British Anti-Lynching

Society.

She was able to debate Frances Willard during her 1894 trip;

Wells had been denouncing a statement of Willard’s that tried to gain support

for the temperance movement by asserting that the black community was opposed

to temperance, a statement that raised the image of drunken black mobs

threatening white women — a theme that played into lynching defense.

Move to Chicago

On returning from her first British trip, Wells moved to Chicago. There, she

worked with Frederick Douglass and a local lawyer and editor, Frederick

Barnett, in writing an 81-page booklet about the exclusion of black

participants from most of the events around the Colmbian Exposition.

She met and married Frederick Barnett who was a widower.

Together they had four children, born in 1896, 1897, 1901 and 1904, and she

helped raise his two children from his first marriage. She also wrote for his

newspaper, the Chicago Conservator.

In 1895 Wells-Barnett published A Red Record: Tabulated

Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynchings in the United States 1892 – 1893 –

1894. She documented that lynchings were not, indeed, caused by black men

raping white women.

From 1898-1902, Wells-Barnett served as secretary of the

National Afro-American Council. In 1898, she was part of a delegation to

President William McKinley to seek justice after the lynching in South Carolina

of a black postman.

In 1900, she spoke for woman suffrage, and worked with another

Chicago woman, Jane Addams, to defeat an attempt to segregate Chicago’s public

school system.

In 1901, the Barnetts bought the first house east of State

Street to be owned by a black family. Despite harassment and threats, they continued

to live in the neighborhood.

Wells-Barnett was a founding member of the NAACP in 1909, but

withdrew her membership, criticizing the organization for not being militant

enough. In her writing and lectures, she often criticized middle-class blacks including

ministers for not being active enough in helping the poor in the black

community.

In 1910, Wells-Barnett helped found and became president of the

Negro Fellowship League, which established a settlement house in Chicago to

serve the many African Americans newly arrived from the South. She worked for

the city as a probation officer from 1913-1916, donating most of her salary to

the organization. But with competition from other groups, the election of an

unfriendly city administration, and Wells-Barnett’s poor health, the League

closed its doors in 1920.

Woman Suffrage

In 1913, Wells-Barnett organized the Alpha Suffrage League, an organization of

African American women supporting woman suffrage. She was active in protesting

the strategy of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, the largest

pro-suffrage group, on participation of African Americans and how they treated

racial issues. The NAWSA generally made participation of African Americans

invisible — even while claiming that no African American women had applied for

membership — so as to try to win votes for suffrage in the South. By forming

the Alpha Suffrage League, Wells-Barnett made clear that the exclusion was

deliberate, and that African American women and men did support woman suffrage,

even knowing that other laws and practices that barred African American men

from voting would also affect women.

A major suffrage demonstration in Washington, DC, timed to align

with the presidential inauguration of Woodrow Wilson, asked that African

American supporters march at the back of the line. Many African American

suffragists, like Mary Church Terrell, agreed, for strategic reasons after

initial attempts to change the minds of the leadership — but not Ida B.

Wells-Barnett. She inserted herself into the march with the Illinois

delegation, after the march started, and the delegation welcomed her. The

leadership of the march simply ignored her action.

Wider Equality Efforts

Also in 1913, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was part of a delegation to see President

Wilson to urge non-discrimination in federal jobs. She was elected as chair of

the Chicago Equal Rights League in 1915, and in 1918 organized legal aid for

victims of the Chicago race riots of 1918.

In 1915, she was part of the successful election campaign that

led to Oscar Stanton De Priest becoming the first African American alderman in

the city.

She was also part of founding the first kindergarten for black

children in Chicago.

Later Years and Legacy

In 1924, Wells-Barnett failed in a bid to win election as president of the

National Association of Colored Women, defeated by Mary McLeod Bethune. In

1930, she failed in a bid to be elected to the Illinois State Senate as an

independent.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett died in 1931, largely unappreciated and

unknown, but the city later recognized her activism by naming a housing project

in her honor. The Ida B. Wells Homes, in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the

South Side of Chicago, included rowhouses, mid-rise apartments, and some

high-rise apartments. Because of the housing patterns of the city, these were

occupied primarily by African Americans. Completed in 1939 to 1941, and

initially a successful program, over time neglect and other urban problems led

to their decay including gang problems. They were torn down between 2002 and

2011, to be replaced by a mixed-income development project.

Although anti-lynching was her main focus, and she did achieve

considerable visibility of the problem, she never achieved her goal of federal

anti-lynching legislation. Her lasting success was in the area of organizing

black women.

Her autobiography Crusade for Justice, on which she worked in

her later years, was published in 1970, edited by her daughter Alfreda M.

Wells-Barnett.

Her home in Chicago is a

National HIstoric Landmark, and is under private ownership. Research more about

this great American and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!