GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is the 17-year-old was playing in her first grand slam quarterfinal, but trailing 4-0 in the second set, a frustrated she smashed her racquet on the clay court after she double faulted.She ran her opponent close in the opening set, with Krejcikova needing a dramatic tiebreak to gain the upper hand in the match.In the second set, the Czech player ramped up the pressure on her younger opponent, winning the first five games without reply.Today in our History – November 29, 2020- Coco Gauff, is defeated in match and breaks racquet.But the American showed experience to belie her age, saving multiple match points and winning three straight games to make things nervy before Krejcikova claimed the second set’s decisive ninth game to reach the semifinals.”I never imagined I would be standing here one day,” the 25-year-old Krejcikova said on court after her victory.Both players were playing in their first career singles grand slam quarterfinals. By reaching the last eight, Gauff had become the youngest woman to compete in a grand slam quarterfinal since 2006.Despite her age, the 17-year-old Gauff didn’t look out of place on the big stage on Court Philippe Chatrier.The No. 24 seed held 3-0 and 5-3 leads in the opening set, but Krejcikova fought back, saving five match points before eventually taking the 72-minute set.Gauff pinpointed losing the first set as the turning point in the match.”I’m obviously disappointed that I wasn’t able to close out the first set,” she told the media after. “To be honest, it’s in the past, it already happened. After the match, my hitting partner told me this match will probably make me a champion in the future. I really do believe that.”That really seemed to kick the world No. 33 into gear.She looked much more comfortable in the second set, manipulating the ball at will, with Gauff struggling to gain any momentum.And leading 5-0 in the second set and needing just one more game to reach her first singles grand slam semifinal, that looked like a formality for Krejcikova with Gauff appearing rattled.However, Gauff showed remarkable strength and resilience to save multiple match points to win three straight games and suggest a previously unthinkable recovery might just be possible.But it was not to be and on Krejcikova’s sixth match point the Czech player clinched the match after one hour and 50 minutes.Krejcikova believes some of her singles success is down to a change in perspective during the Covid-19 shutdown.”Seeing that there are also other things in the world that actually are happening,” she said. “[That] are tougher and more difficult than just me playing tennis and losing.”It just got to my mind. I’m like, Well, I go and I play tennis and I lose, but there are actually people that are losing their lives. I just felt more like, Well, just relax because you are healthy. Just appreciate this and just enjoy the game.You can do something what maybe other people would like to do as well but they cannot.”Krejcikova will face defending champion Iga Swiatek or Greece’s Maria Sakkari for a place in the final at Roland Garros. Research more about this great American Champio and shate it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

Month: November 2021

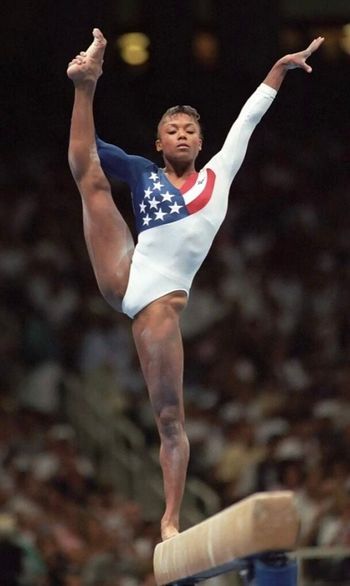

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is one of the most renowned names in the history of American gymnastics, she recognized her passion for gymnastics at an early age of 6 years and attended lessons with Kelli Hill who remained her coach for the rest of her gymnastics career.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is one of the most renowned names in the history of American gymnastics, she recognized her passion for gymnastics at an early age of 6 years and attended lessons with Kelli Hill who remained her coach for the rest of her gymnastics career.Today in our History – November 20, 1976 – Dominique Dawes was born.With her skills and determination, Dawes soon became a force to be reckoned with in the field of gymnastics and at the young age of 12, became the first African American to earn a spot in the national women’s team. In 1992, Dawes joined the U.S. Olympic artistic gymnastics team which won the bronze medal in Barcelona. In the 1994 National Championships, she won all-around gold and four individual events, vault, uneven bars, balance beam and floor exercise, becoming the first gymnast to win all five gold medals since 1969.Making the cut for the 1996 U.S. Olympic team, Dawes led the Magnificent Seven to the first position, making the squad the first U.S. women’s gymnastics team to do so in the history of Olympics. A few small mistakes, including a fall, hindered Dawes’ contention for the all-around competition medal. However, she earned herself the title of the first African American to win an individual medal in women’s gymnastics by displaying the best floor performance.Dawes successfully maintained a balance between her academic and sports careers, attending Standford University on an athletic scholarship which she had received upon graduating from Gaithersburg High School but had deferred her enrollment until after the 1996 Olympics. Being an all-rounder, she also began pursuing a career in arts around the same time, involving herself in acting, television production and modeling. Appearing in the famous Broadway musical, Grease, Dominique Dawes also worked for Disney Television and one of Prince’s music videos.Justifying to her reputation of Awesome Dawesome, Dawes continued to train while gaining higher education in 2000 and made it to U.S. Olympic team for a third time. Initially finishing in fourth place, the team was moved prized with a bronze medal after a Chinese competitor was disqualified. Thus, Dawes became the first U.S. gymnast to be a part of three different medal-winning teams and made record of the most trips to the Olympics by a female U.S. gymnast.The same year, Dawes permanently retired from gymnastics and put her efforts into other fields. Giving back to the community, Dawes served as the President of the Women’s Sports Foundation and was also a part of Michelle Obama’s ‘Let’s Move Active Schools’ campaign. In 2010, Dawes also became Co-Chair of the President’s Council on Fitness, Sports and Nutrition. The former gymnast also earned herself a spot in USA’s Gymnastics’ Hall of Fame in 2005.Encouraging young individuals to be active, Dawes gives private lessons at her home gym and holds a position on the advisory board for Sesame Workshop’s ‘Healthy Habits for Life’. Dawes also served as the National Spokesperson for Uniquely Me, the Unilever Self-Esteem program, where she gave tips to girls regarding self-esteem issues and guided them by sharing her personal experiences.Dominique Dawes maintained her connection with gymnastics by covering the 2008 and 2012 Olympic Games and witnessed Gabby Douglas become the first African American to win an individual gold medal in the all-around competition in 2012. Dawes hoped that Douglas would be able to inspire young girls and serve as their role model in a manner similar to hers. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was called all kinds of names by his own people for taking roles that projected Blacks as inferior.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was called all kinds of names by his own people for taking roles that projected Blacks as inferior. I learned from my great Uncle Leon Busby the real history and from then on I would correct people when they called our people on the screen or movies what the truth was. Today’s Champion was an American vaudevillian, comedian, and film actor of Jamaican and Bahamian descent, considered to be the first Black actor to have a successful film career. His highest profile was during the 1930s in films and on stage, when his persona of Stepin Fetchit was billed as the “Laziest Man in the World”.He parlayed the Fetchit persona into a successful film career, becoming the first Black actor to earn $1 million. He was also the first Black actor to receive featured screen credit in a film.His film career slowed after 1939 and nearly stopped altogether after 1953. Around that time, Black Americans began to see his Stepin Fetchit persona as an embarrassing and harmful anachronism, echoing negative stereotypes. However, the Stepin Fetchit character has undergone a re-evaluation by some scholars in recent times, who view him as an embodiment of the trickster archetype Today in our History – November 19, 1985 – Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry (May 30, 1902 – November 19, 1985), better known by the stage name Stepin Fetchit died.Little is known about Perry’s background other than that he was born in Key West, Florida, to West Indian immigrants. He was the second child of Joseph Perry, a cigar maker from Jamaica (although some sources indicate the Bahamas) and Dora Monroe, a seamstress from Nassau, The Bahamas.Both of his parents came to the United States in the 1890s, where they married. By 1910, the family had moved north to Tampa, Florida. Another source says he was adopted when he was 11 years old and taken to live in Montgomery, Alabama.His mother wanted him to be a dentist, so Perry was adopted by a quack dentist, for whom he blacked boots before running away at age 12 to join a carnival. He earned his living for a few years as a singer and tap dancer.In his teens, Perry became a comic character actor. By the age of 20, Perry had become a vaudeville artist and the manager of a traveling carnival show. His stage name was a contraction of “step and fetch it”. His accounts of how he adopted the name varied, but generally he claimed that it originated when he performed a vaudeville act with a partner.Perry won money betting on a racehorse named “Step and Fetch It”, and his partner and he decided to adopt the names “Step” and “Fetchit” for their act. When Perry became a solo act, he combined the two names, which later became his professional name.Perry played comic-relief roles in a number of films, all based on his character known as the “Laziest Man in the World”. In his personal life, he was highly literate and had a concurrent career writing for The Chicago Defender.He signed a five-year studio contract following his performance in the film, In Old Kentucky (1927). The film’s plot included a romantic connection between Perry and actress Carolynne Snowden, a subplot that was a rarity for Black actors appearing in a White film during this era. Perry also starred in Hearts in Dixie (1929), one of the first studio productions to boast a predominantly Black cast.Jules Bledsoe provided Perry’s singing voice for his role as Joe in the 1929 version of Show Boat. Fetchit did not sing “Ol’ Man River”, but he did sing “The Lonesome Road” in the film. In 1930, Hal Roach signed him to a film contract to appear in nine Our Gang episodes in 1930 to 1931. He was in the 1929-30 film A Tough Winter; his contract was cancelled after its release.Perry was good friends with fellow comic actor Will Rogers.[4] They appeared together in David Harum (1934), Judge Priest (1934), Steamboat ‘Round the Bend (1935), and The County Chairman (1935).By the mid-1930s, Perry was the first Black actor to become a millionaire. He appeared in 44 films between 1927 and 1939. In 1940, Perry temporarily stopped appearing in films, having been frustrated by his unsuccessful attempt to get equal pay and billing with his White costars. He returned in 1945, in part due to financial need, though he only appeared in eight films between 1945 and 1953.He declared bankruptcy in 1947, stating assets of $146 (equrato about $1,692 today) He returned to vaudeville; he appeared at the Anderson Free Fair in 1949 alongside Singer’s Midgets. He became a friend of heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali in the 1960s, converting to the Nation of Islam shortly before.After 1953, Perry appeared in cameos in the made-for-television movie Cutter (1972) and the feature films Amazing Grace (1974) and Won Ton Ton, the Dog Who Saved Hollywood (1976). He found himself in conflict during his career with civil rights leaders who criticized him personally for the film roles that he portrayed.In 1968, CBS aired the hour-long documentary Black History: Lost, Stolen, or Strayed, written by Andy Rooney (for which he received an Emmy Award) and narrated by Bill Cosby, which criticized the depiction of blacks in American film, and especially singled out Stepin Fetchit for criticism. After the show aired, Perry unsuccessfully sued CBS and the documentary’s producers for defamation of character.In late November 1963, Perry collaborated with Motown Records founder Berry Gordy Jr. and Esther Gordy Edwards in composing “May What He Lived for Live,” a song intended to honor the memory of President John F. Kennedy in the wake of his assassination.Perry was credited under the pseudonym W.A. Bisson. The song was recorded in December 1963 by Liz Lands, who in 1968 performed the work at the funeral of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.Fetchit has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.In 1976, despite popular aversion to his character, the Hollywood chapter of the NAACP awarded Perry a special NAACP Image Award. Two years later, he was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame.Perry spawned imitators, such as Willie Best (“Sleep ‘n Eat”) and Mantan Moreland, the scared, wide-eyed manservant of Charlie Chan. Perry had actually played a manservant in the Chan series before Moreland in 1935’s Charlie Chan in Egypt.)Perry appeared in one 1930 Our Gang short subject, A Tough Winter, at the end of the 1929–30 season. Perry signed a contract to star with the gang in nine films for the 1930–31 season and be part of the Our Gang series, but for some unknown reason, the contract fell through, and the gang continued without Perry.Previous to Perry entering films, the Our Gang shorts had employed several Black child actors, including Allen Hoskins, Jannie Hoskins, Ernest Morrison, and Eugene Jackson. In the sound Our Gang era black actors Matthew Beard and Billie Thomas were featured. The Black performers’ personas in Our Gang shorts were the polar opposites of Perry’s persona.Gordon Lightfoot referenced Stepin Fetchit in his 1970 song “Minstrel of the Dawn” on the album Sit Down Young Stranger.In the 2005 book Stepin Fetchit: The Life and Times of Lincoln Perry, African-American critic Mel Watkins argued that the character of Stepin Fetchit was not truly lazy or simple-minded, but instead a prankster who deliberately tricked his White employers so that they would do the work instead of him.This technique, which developed during American slavery, was referred to as “putting on old massa”, and it was a kind of con art with which Black audiences of the time would have been familiar.In 1929, Perry married 17-year-old Dorothy Stevenson. She gave birth to their son, Jemajo, on September 12, 1930. In 1931, Dorothy filed for divorce, stating that Perry had broken her nose, jaw, and arm with “his fists and a broomstick.” A few weeks after their divorce was granted, Dorothy told a reporter she hoped someone would “just beat the devil out of him,” as he had done to her. When Dorothy contracted tuberculosis in 1933, Perry moved her to Arizona for treatment. She died in September 1934.Perry reportedly married Winifred Johnson in 1937, but no record of their union has been found. On May 21, 1938, Winifred gave birth to a son she named Donald Martin Perry. Their relationship ended soon after Donald’s birth.According to Winifred’s brother Stretch Johnson, their father intervened after Perry knocked Winifred down the stairs and broke her nose. In 1941, Perry was arrested after Winifred filed a suit for child support. When he was released from jail, he told reporters, “Winnie and I were never married.It was all a publicity stunt. I want you and everybody else to know that that is not my baby. Winnie knows the baby isn’t mine but she’s trying to be smart.” Winifred admitted that they were not legally married, but she insisted Perry was her son’s father. The court ruled in her favor and ordered Perry to pay $12 a week (almost $220 in 2020 dollars) for the child’s support. Donald later took his stepfather’s surname, Lambright.Perry married Bernice Sims on October 15, 1951. Although they separated by the mid-1950s, they remained married for the rest of their lives. Bernice died on January 9, 1985.On April 5, 1969, Donald Lambright traveled the Pennsylvania Turnpike shooting people. Reportedly, he injured 16 and killed four, including his wife, with an M1 carbine and a .30-caliber Marlin 336 carbine before turning one of the rifles on himself.The 1969 Pennsylvania Turnpike shooting was ruled a murder-suicide, but the account of the circumstances upon which the ruling was based was questioned by Lambright’s daughter and discussed at length in her 2005 self-published book about Stepin Fetchit.In a Los Angeles Times interview, Lincoln Perry stated his belief that his son was set up. Lambright’s involvement with the Black Power movement at the peak of the COINTELPRO program was believed to be related to his death. Perry never provided child support for Lambright, and they only met two years before his son’s violent death.Perry suffered a stroke in 1976, ending his acting career; he then moved into the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital. He died on November 19, 1985, from pneumonia and heart failure at the age of 83.He was buried at Calvary Cemetery in East Los Angeles with a Catholic funeral Mass. Research more about this great American Champion and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!

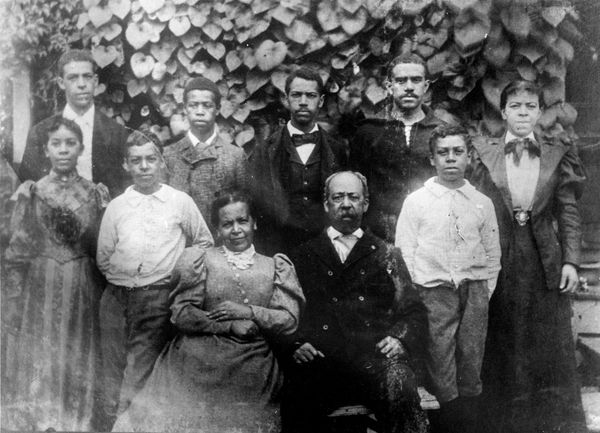

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a former slave and veteran of the American Civil War, serving in the U.S. Navy.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a former slave and veteran of the American Civil War, serving in the U.S. Navy. His diary is one of only a few written during the Civil War by former slaves that have survived, and then only by a formerly enslaved sailor.Today in our History – November 18, 1837 – William Benjamin Gould (November 18, 1837 – May 25, 1923) was born.William B. Gould was born in Wilmington, North Carolina on November 18, 1837, to an enslaved woman, Elizabeth “Betsy” Moore, and Alexander Gould, an English-born resident of Granville County, NC. He was enslaved by Nicholas Nixon, a peanut farmer who owned Poplar Grove, a plantation on Porters Neck. Gould worked as a plasterer at the antebellum Bellamy Mansion in Wilmington, North Carolina, and carved his initials into some of the plaster there.The outbreak of the Civil War brought danger to Wilmington in the form of crime, disease, the threat of invasion, and “downright bawdiness.” This prompted many slave owners to move inland, resulting in less supervision over those they were enslaving. During a rainy night on September 21, 1862, Gould escaped with seven other enslaved men by rowing a small boat 28 nautical miles (52 km) down the Cape Fear River. They embarked on Orange Street, just four blocks from where Gould lived on Chestnut St. Sentries were posted along the river, adding additional danger. The boat had a sail, but they did not raise it until they were out in the Atlantic for fear of being seen.Just as the dawn was breaking on September 22, they rushed out into the Atlantic Ocean near Fort Caswell and hoisted their sail. There, the USS Cambridge of the Union blockade picked them up as contraband. Other ships in the blockade picked up two other boats containing friends of Gould in what may have been a coordinated effort. Though Gould had no way of knowing it, within an hour and a half of his rescue President Abraham Lincoln convened a meeting of his cabinet to finalize plans to issue the Emancipation Proclamation.During the war, his home was burned, and with it a family Bible. His birthday was inscribed in that Bible but that was the only record of his birth.There had been some concern about the numbers of slaves who were escaping and making it to Union ships before Gould’s escape. One captain had written to the Navy Department asking what was to be done with them as they did not have room for the extra men.William A. Parker, the captain of the Cambridge, however, had written to Acting Rear Admiral Samuel Phillips Lee just five days before picking up Gould that his ship was short 18 men due to desertions and sickness. As a result, he said, he intended to fill the vacancies with escaped slaves.After his boarding, the Cambridge, Gould notes that he was “kindly received by officers and men.” In his diary, he noted that on October 3, 1862, he took “the Oath of Allegiance to the Government of Uncle Samuel.” Upon joining the U.S. Navy onboard the Cambridge, he was given the rank of First Class Boy.At the time, boy was the highest rank a black sailor could earn. He was later promoted to landsman and then wardroom steward, making him a petty officer but without the authority that came as an officer of the line.The Cambridge was part of the Atlantic Blockading Squadron, enforcing the blockade of the Confederate coastline. Gould found the work to be difficult and lonely, recording after just three months on the ship that all the men had the blues. Still, Gould believed he was “defending the holiest of all causes, Liberty and Union.” During his service, he saw combat and chased Confederate ships across the Atlantic Ocean to Europe. In a span of five days, the Cambridge and two other ships were able to capture four blockade runners and chase a fifth to shore.Gould also served on the USS Ohio. While onboard of Ohio, he came down with measles and had to leave the ship to go to the hospital. His time in the hospital, from May to October 1863, is the only time he broke from his habit of writing in his diary. During this time he was visited by one of his maternal cousins, Jones, who was the child of emancipated slaves who moved north for fear of being re-enslaved.In October 1863, after he was recovered, Gould was transferred to the USS Niagra. The ship was in port in Gloucester, Massachusetts, waiting for a full complement of men. On December 10, it unexpectedly left port and raced up the eastern seaboard to Nova Scotia chasing after the Chesapeake. The Chesapeake had been captured off the coast of Cape Cod by Confederate sympathizers from the Maritime Provinces.From June 1, 1864, until well into 1865, Gould and the Niagra sailed to and around Europe, searching for Confederate ships. The Niagra was involved in two major confrontations while in Europe, including the taking of the CSS Georgia. It stalked the CSS Stonewall along the coasts of Spain and Portugal but declined to fight the armored ship and let it get away. It was also on the hunt for the CSS Alabama, the CSS Florida, the CSS Shenandoah, and the Laurel, but they did not find them.While off the coast of Cadiz, Spain, those on board the Niagra learned of the surrender of the Confederate Army. “I heard the Glad Tidings that the Stars and Stripes had been planted over the Capital of the D–d Confederacy by the invincible Grant,” Gould committed to his diary. Not knowing that it signaled the end of the war, the Niagra set sail again, this time searching for Confederate ships in Queenstown, Ireland. The Irish came out in great numbers to see the American warship. Leaving Ireland, the Niagra sailed to Charlestown, Massachusetts, where Gould received an honorable discharge after three years of service in the United States Navy.During his first leave from the ship in the spring of 1863, Gould visited his Mary Moore Jones, his maternal aunt, in Boston, and then his eventual wife, Cornelia Reed, on Nantucket. There were a number of other women that he visited in New York during his leaves as well. Gould had an active social life during her leaves, attending concerts, lectures, and public meetings. During his time in New York, he also met William McLaurin, a future North Carolina state representative.Though black men served alongside white men in the Navy during the Civil War and made up roughly 15% of the Union Navy, Gould experienced racism while serving onboard the USS Cambridge. Black soldiers from a Maryland regiment who had been taken aboard temporarily were “treated shamefully,” Gould said when they were not allowed to eat out of mess pans and were called disparaging names. The incident seemed to be out of the ordinary, suggesting that it was not common while serving.Gould visited Wilmington after the war, perhaps in October 1865, and found it to be largely deserted, very unlike the bustling city he knew before the war. He found it to be an improvement, however, where many of the trappings of the former slave economy had been removed.Gould married in 1865 and spent his first year as a married man working as a plasterer on Nantucket. After living in New Hampshire and in Taunton, Massachusetts for a time, in 1871 the Goulds moved to 303-307 Milton Street in Dedham, Massachusetts. In Dedham, Gould became a building contractor and pillar of the community. Gould “took great pride in his work” as a plasterer and brick mason. His skill was rewarded with contracts for public buildings, including several schools.He helped to build the new St. Mary’s Church in his adopted hometown of Dedham. While working on the church, one of his employees improperly mixed the plaster. Even though it was not visible by looking at it and though the defect would not be discovered for some time, Gould insisted that it be removed and reapplied correctly. The decision nearly bankrupted him, but it helped cement his reputation in the town. He also worked as a stonemason, constructing buildings around Dedham.He later took the minutes of the Hancock Mutual Relief Association.Shortly before he got sick with the measles, Gould met John Robert Bond, another black sailor serving on the Ohio. The Gould home was close to the border with Readville, where Bond settled after the war. The two would reconnect ten years after the war and become good friends. Gould would later serve as godfather to Bond’s second son.Gould helped to build the Episcopal Church of the Good Shepard in Oakdale Square, though as a parishioner and not as a contractor. He and his wife were baptized and confirmed there in 1878 and 1879.As a signer of the Articles of Incorporation, he was one of its founders. Gould’s family remained active members of the church and, along with the Bonds and one other family, the Chesnuts were the only black parishioners. There was only one other black family in Dedham at the time. Gould and his family were more likely to experience subtle slights on account of their race as opposed to outright racism while living in Dedham.Gould was extremely active in the Charles W. Carroll Post 144 of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). He “held virtually every position that it was possible to hold in the GAR from the time he joined [in 1882] until his death in 1923, including the highest post, commander, in 1900 and 1901.” He attended the statewide encampments of the GAR in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with Bond and other black veterans from the area. He also joined the Mt. Moriah Masonic Prince Hall Lodge in Cambridge with several other black veterans. In 1911, Gould was interviewed by the local veteran’s association about his wartime experiences.By 1886, Gould would earn enough esteem in the community to be appointed to the General Staff and to lead the parade held in honor of Dedham’s 250th anniversary. Gould gave a speech at Dedham’s 1918 Decoration Day celebrations at which he received “an ovation welcome.” He also regularly spoke to school children on Memorial Day and presided over the town’s celebrations of the holiday. Gould was driven through town on parade days into the 1920s in cars adorned with red, white, and blue decorations.Gould was a committed Republican, as were his children. He adamantly opposed the notion that newly emancipated blacks should be repatriated to Africa or Haiti, saying they had been born under the American flag and would know no other.After he was discharged from the Navy on September 29, 1865, at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Massachusetts, Gould considered moving back to North Carolina where he believed he would have “a fair chance of success [in] my business”. Instead, he immediately went to Nantucket where he married Cornelia Williams Read, on November 22, 1865, at the African Baptist Church on Nantucket. Rev. James E. Crawford, Read’s uncle, officiated. Gould had known Read since childhood, and she was his most frequent wartime correspondent. Cornelia, who had been purchased out of slavery, was then living on Nantucket.Their oldest daughter, Medora Williams, was born on Nantucket, and their oldest son, William B. Gould Jr., was born in Taunton. The rest, Fredrick Crawford, Luetta Ball, Lawrence Wheeler, Herbert Richardson, and twins James Edward and Ernest Moore, were all born in Dedham.The 1880 United States census lists a boy with the last name of Mabson living with the Goulds and working as an employee of Goulds. The child is almost certainly the son of one of Gould’s nephews through his sister Eliza, George Lawrence Mabson or William Mabson.Five of his sons would fight in World War I and one in the Spanish–American War. A photo of the six sons and their father, all in military uniform, would appear in the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, in December 1917. The three youngest sons, all officers, were training to go and fight in World War I in France. Gould’s great-grandson would describe them as “a family of fighters.”It is unknown where Gould learned to read and write as it was illegal to teach those skills to slaves. However, it is clear that he was educated and able to express himself elegantly. In his diary, Gould quoted Shakespeare, had some knowledge of French, and knew a handful of Spanish expressions. It is possible that he was educated in the Front Street Methodist Church near Nixon’s slave quarters, or at St. John’s Episcopal Church.During stops in New York while in the Navy, Gould frequently visited the offices of The Anglo-African, an abolitionist newspaper. Gould raised funds for the publication, become an avid reader, and serve as a correspondent under the nom de plume “Oley.” While onboard the Niagra, Gould often corresponded with Robert Hamilton, the publisher.During the war, Gould sent and received a large number of letters. None of them survive, but each is noted in his diary. They include family, friends, former shipmates, other contraband, and acquaintances in North Carolina, New York, Massachusetts. He corresponds frequently with George W. Price who escaped with him, and with Abraham Galloway, both of whom served in the North Carolina General Assembly after the war. He most frequently writes to his eventual wife, Cornelia Reed, and they exchange at least 60 letters during the war. Cornelia attended school after she moved to Nantucket; it is unclear whether she knew how to read and write prior.Beginning with his time on the Cambridge and continuing through his discharge at the end of the war, Gould kept a diary of his day-to-day activities. According to John Hope Franklin, Gould’s diary is one of three known diaries in existence written during the Civil War by former slaves, and the only one by a Union sailor. It is a “wealth of information about what it was like to be an African-American in the Union Navy.”The diary begins on September 27, 1862, five days after boarding the Cambridge, and runs until his discharge on September 29, 1865. There is a section missing, which included the dates of September 1863 to February 1864. It consists of two books plus 40 unbound pages. It is thought that some sections of the diary, which would cover late 1864 and early 1865, have been destroyed.In the diary, Gould chronicles his trips to the northeastern United States, the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, Portugal, and England. The diary is distinguished not only by its details and eloquent tone, but also by its author’s reflections on the conduct of the war, his own military engagements, race, race relations in the Navy, and what African Americans might expect after the war and during the Reconstruction Era.Gould died on May 25, 1923, at the age of 85, and was interred at Brookdale Cemetery in Dedham. The Dedham Transcript reported his death under the headline “East Dedham Mourns Faithful Soldier and Always Loyal Citizen: Death Came Very Suddenly to William B. Gould, Veteran of the Civil War.”Gould’s diary was discovered 35 years after his death, in 1958, when his attic was being cleaned out. His grandson, William B. Gould III, showed it to his son, William B. Gould IV. At the time, they had known that Gould served in the Navy during the Civil War, but not if he had been enslaved or free prior to his service.Gould IV began researching his ancestor’s life, a process that would last more than 50 years. While teaching at Harvard in the 1970s, Gould IV researched his namesake’s life in nearby Dedham. When he served as the chairman of the National Labor Relations Board under President Bill Clinton in the 1990s, he searched the National Archives. It was only in 1989 that Gould IV discovered his ancestor had been enslaved prior to the war. Gould IV found a notation in the log of the Cambridge that noted Gould had been picked up as contraband and listed the name of his enslaver.Gould IV went on to edit his great-grandfather’s diary and publish it as a book titled Diary of a Contraband: The Civil War Passage of a Black Sailor. He donated the original diary to the Massachusetts Historical Society in 2006.The forward to the published edition was written by the United States, Senator Mark O. Hatfield. According to Hatfield, Gould’s “outstanding life, in Dedham, Massachusetts, following the war, exemplifies American citizenship at its best–citizenship that burned brightly because our nation transcended the inhumanity of slavery.”Gould’s diary was featured in the July 3, 2001, edition of Nightline. In 2020, the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts donated copies of the book to local schools and libraries.On November 9, 2020, the Town of Dedham renamed a 1.3-acre park the William B. Gould Memorial Park. A committee was established to erect a memorial to him on the site. A pew at the Church of the Good Shepherd is dedicated to Gould and Cornelia. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

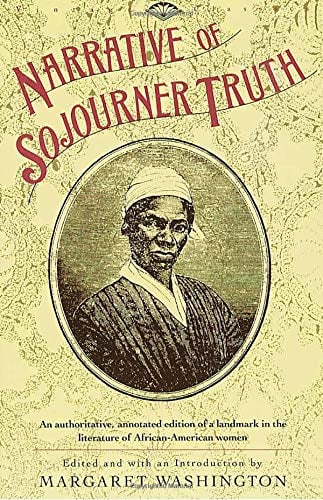

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American abolitionist and women’s rights activist.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American abolitionist and women’s rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to freedom in 1826. After going to court to recover her son in 1828, she became the first black woman to win such a case against a white man.She gave herself the name Sojourner Truth in 1843 after she became convinced that God had called her to leave the city and go into the countryside “testifying the hope that was in her”. Her best-known speech was delivered extemporaneously, in 1851, at the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. The speech became widely known during the Civil War by the title “Ain’t I a Woman?”, a variation of the original speech re-written by someone else using a stereotypical Southern dialect, whereas Sojourner Truth was from New York and grew up speaking Dutch as her first language. During the Civil War, Truth helped recruit black troops for the Union Army; after the war, she tried unsuccessfully to secure land grants from the federal government for formerly enslaved people (summarized as the promise of “forty acres and a mule”). She continued to fight on behalf of women and African Americans until her death. As her biographer Nell Irvin Painter wrote, “At a time when most Americans thought of slaves as male and women as white, Truth embodied a fact that still bears repeating: Among the blacks are women; among the women, there are blacks.” A memorial bust of Truth was unveiled in 2009 in Emancipation Hall in the U.S. Capitol Visitor’s Center. She is the first African American woman to have a statue in the Capitol building. In 2014, Truth was included in Smithsonian magazine’s list of the “100 Most Significant Americans of All Time”.Today in our History – November 17, 1787 – Sojourner Truth born Isabella “Belle” Baumfree; c. 1797 – November 26, 1883 was born. Truth was one of the 10 or 12 children born to James and Elizabeth Baumfree (or Bomefree). Colonel Hardenbergh bought James and Elizabeth Baumfree from slave traders and kept their family at his estate in a big hilly area called by the Dutch name Swartekill (just north of present-day Rifton), in the town of Esopus, New York, 95 miles (153 km) north of New York City. Charles Hardenbergh inherited his father’s estate and continued to enslave people as a part of that estate’s property. When Charles Hardenbergh died in 1806, nine-year-old Truth (known as Belle), was sold at an auction with a flock of sheep for $100 to John Neely, near Kingston, New York. Until that time, Truth spoke only Dutch. She later described Neely as cruel and harsh, relating how he beat her daily and once even with a bundle of rods. In 1808 Neely sold her for $105 to tavern keeper Martinus Schryver of Port Ewen, New York, who owned her for 18 months. Schryver then sold Truth in 1810 to John Dumont of West Park, New York. John Dumont was a rapist and considerable tension existed between Truth and Dumont’s wife, Elizabeth Waring Dumont, who harassed her and made her life more difficult. Around 1815, Truth met and fell in love with an enslaved man named Robert from a neighboring farm. Robert’s owner (Charles Catton, Jr., a landscape painter) forbade their relationship; he did not want the people he enslaved to have children with people he was not enslaving, because he would not own the children. One day Robert sneaked over to see Truth. When Catton and his son found him, they savagely beat Robert until Dumont finally intervened. Truth never saw Robert again after that day and he died a few years later. The experience haunted Truth throughout her life.Truth eventually married an older enslaved man named Thomas. She bore five children: James, her firstborn, who died in childhood, Diana (1815), the result of a rape by John Dumont, and Peter (1821), Elizabeth (1825), and Sophia (ca. 1826), all born after she and Thomas united. In 1799, the State of New York began to legislate the abolition of slavery, although the process of emancipating those people enslaved in New York was not complete until July 4, 1827. Dumont had promised to grant Truth her freedom a year before the state emancipation, “if she would do well and be faithful”. However, he changed his mind, claiming a hand injury had made her less productive. She was infuriated but continued working, spinning 100 pounds (45 kg) of wool, to satisfy her sense of obligation to him. Late in 1826, Truth escaped to freedom with her infant daughter, Sophia. She had to leave her other children behind because they were not legally freed in the emancipation order until they had served as bound servants into their twenties. She later said, “I did not run off, for I thought that wicked, but I walked off, believing that to be all right.” She found her way to the home of Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen in New Paltz, who took her and her baby in. Isaac offered to buy her services for the remainder of the year (until the state’s emancipation took effect), which Dumont accepted for $20. She lived there until the New York State Emancipation Act was approved a year later. Truth learned that her son Peter, then five years old, had been sold illegally by Dumont to an owner in Alabama. With the help of the Van Wagenens, she took the issue to court and in 1828, after months of legal proceedings, she got back her son, who had been abused by those who were enslaving him. Truth became one of the first black women to go to court against a white man and win the case. Truth had a life-changing religious experience during her stay with the Van Wagenens and became a devout Christian. In 1829 she moved with her son Peter to New York City, where she worked as a housekeeper for Elijah Pierson, a Christian Evangelist. While in New York, she befriended Mary Simpson, a grocer on John Street who claimed she had once been enslaved by George Washington. They shared an interest in charity for the poor and became intimate friends. In 1832, she met Robert Matthews, also known as Prophet Matthias, and went to work for him as a housekeeper at the Matthias Kingdom communal colony. Elijah Pierson died, and Robert Matthews and Truth were accused of stealing from and poisoning him. Both were acquitted of the murder, though Matthews was convicted of lesser crimes, served time, and moved west. In 1839, Truth’s son Peter took a job on a whaling ship called the Zone of Nantucket. From 1840 to 1841, she received three letters from him, though in his third letter he told her he had sent five. Peter said he also never received any of her letters. When the ship returned to port in 1842, Peter was not on board and Truth never heard from him again. In 1851, Truth joined George Thompson, an abolitionist and speaker, on a lecture tour through central and western New York State. In May, she attended the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, where she delivered her famous extemporaneous speech on women’s rights, later known as “Ain’t I a Woman?”.Her speech demanded equal human rights for all women. She also spoke as a former enslaved woman, combining calls for abolitionism with women’s rights, and drawing from her strength as a laborer to make her equal rights claims.The convention was organized by Hannah Tracy and Frances Dana Barker Gage, who both were present when Truth spoke. Different versions of Truth’s words have been recorded, with the first one published a month later in the Anti-Slavery Bugle by Rev. Marius Robinson, the newspaper owner and editor who was in the audience. Robinson’s recounting of the speech included no instance of the question “Ain’t I a Woman?” Noraid any of the other newspapers reporting of her speech at the time. Twelve years later, in May 1863, Gage published another, very different, version. In it, Truth’s speech pattern appeared to have characteristics of Southern slaves, and the speech was vastly different than the one Robinson had reported. Gage’s version of the speech became the most widely circulated version, and is known as “Ain’t I a Woman?” because that question was repeated four times. It is highly unlikely that Truth’s own speech pattern was Southern in nature, as she was born and raised in New York, and she spoke only upper New York State low-Dutch until she was nine years old. In the version recorded by Rev. Marius Robinson, Truth said:I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights. I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal. I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as any man that is now. As for intellect, all I can say is, if a woman have a pint, and a man a quart – why can’t she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much, – for we can’t take more than our pint’ll hold. The poor men seems to be all in confusion, and don’t know what to do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights, give it to her and you will feel better. You will have your own rights, and they won’t be so much trouble. I can’t read, but I can hear. I have heard the Bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin. Well, if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again. The Lady has spoken about Jesus, how he never spurned woman from him, and she was right. When Lazarus died, Mary and Martha came to him with faith and love and besought him to raise their brother. And Jesus wept and Lazarus came forth. And how came Jesus into the world? Through God who created him and the woman who bore him. Man, where was your part? But the women are coming up blessed be God and a few of the men are coming up with them. But man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, he is surely between a hawk and a buzzard.In contrast to Robinson’s report, Gage’s 1863 version included Truth saying her 13 children were sold away from her into slavery. Truth is widely believed to have had five children, with one sold away, and was never known to boast more children. Gage’s 1863 recollection of the convention conflicts with her own report directly after the convention: Gage wrote in 1851 that Akron in general and the press, in particular, were largely friendly to the woman’s rights convention, but in 1863 she wrote that the convention leaders were fearful of the “mobbish” opponents. Other eyewitness reports of Truth’s speech told a calm story, one where all faces were “beaming with joyous gladness” at the session where Truth spoke; that not “one discordant note” interrupted the harmony of the proceedings. In contemporary reports, Truth was warmly received by the convention-goers, the majority of whom were long-standing abolitionists, friendly to progressive ideas of race and civil rights. In Gage’s 1863 version, Truth was met with hisses, with voices calling to prevent her from speaking. Other interracial gatherings of black and white abolitionist women had in fact been met with violence, including the burning of Pennsylvania Hall.According to Frances Gage’s recount in 1863, Truth argued, “That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody helps me any best place. And ain’t I a woman?” Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman” showed the lack of recognition that black women received during this time and whose lack of recognition will continue to be seen long after her time. “Black women, of course, were virtually invisible within the protracted campaign for woman suffrage”, wrote Angela Davis, supporting Truth’s argument that nobody gives her “any best place”; and not just her, but black women in general. Over the next 10 years, Truth spoke before dozens, perhaps hundreds, of audiences. From 1851 to 1853, Truth worked with Marius Robinson, the editor of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Bugle, and traveled around that state speaking. In 1853, she spoke at a suffragist “mob convention” at the Broadway Tabernacle in New York City; that year she also met Harriet Beecher Stowe. In 1856, she traveled to Battle Creek, Michigan, to speak to a group called the “Friends of Human Progress”.Truth was cared for by two of her daughters in the last years of her life. Several days before Sojourner Truth died, a reporter came from the Grand Rapids Eagle to interview her. “Her face was drawn and emaciated and she was apparently suffering great pain. Her eyes were very bright and mind alert although it was difficult for her to talk.” Truth died early in the morning on November 26, 1883, at her Battle Creek home. On November 28, 1883, her funeral was held at the Congregational-Presbyterian Church officiated by its pastor, the Reverend Reed Stuart. Some of the prominent citizens of Battle Creek acted as pall-bearers; nearly one thousand people attended the service. Truth was buried in the city’s Oak Hill Cemetery. Frederick Douglass offered a eulogy for her in Washington, D.C. “Venerable for age, distinguished for insight into human nature, remarkable for independence and courageous self-assertion, devoted to the welfare of her race, she has been for the last forty years an object of respect and admiration to social reformers everywhere.” Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American civil rights leader, activist, ordained minister, businessman, philanthropist, scientist, and politician.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American civil rights leader, activist, ordained minister, businessman, philanthropist, scientist, and politician. He may be best known as a trusted member of fellow famed civil rights activist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Martin Luther King Jr.’s inner circle.Under the banner of their flagship organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, King depended on him to organize and stir masses of people into nonviolent direct action in myriad protest campaigns they waged against racial, political, economic, and social injustice.King alternately referred to him, his chief field lieutenant, as his “bull in a china closet” and his “Castro.” Vowing to continue King’s work for the poor, he is well known in his own right as the founding president of one of the largest social services organizations in North America, His Feed the Hungry and Homeless. His famous motto was “Unbought and Unbossed.”Today in our History – November 16, 200 – Hosea Lorenzo Williams (January 5, 1926 – November 16, 2000) died.Williams was born in Attapulgus, Georgia, a small city in the far southwest corner of the state in Decatur County. Both of his parents were teenagers committed to a trade institute for the blind in Macon.His mother ran away from the institute upon learning of her pregnancy. At the age of 28, Williams stumbled upon his birth father, “Blind” Willie Wiggins, by accident in Florida. His mother died during childbirth when he was 10 years old.He and his older sister, Theresa, were raised by his mother’s parents, Lelar and Turner Williams. Williams was run out of town by a lynch mob at the age of 13 for allegedly consorting with a white girl.Williams served with the United States Army during World War II in an all-African-American unit under General George S. Patton, Jr. and advanced to the rank of Staff Sergeant. He was the only survivor of a Nazi bombing, which left him in a hospital in Europe for more than a year and earned him a Purple Heart.Upon his return home from the war, Williams was savagely beaten by a group of angry whites at a bus station for drinking from a water fountain marked “Whites Only.” He was beaten so badly that the attackers thought he was dead. They called a black funeral home in the area to pick up the body.En route to the funeral home, the hearse driver noticed Williams had a faint pulse and was barely breathing, but was still alive. There were no hospitals in the area that would serve blacks, even in the case of a medical emergency; the trip to the nearest veterans’ hospital was well over a hundred miles. Williams spent more than a month hospitalized recuperating from injuries sustained in the attack.Of the attack, Williams was quoted as saying, “I was deemed 100 percent disabled by the military and required a cane to walk. My wounds had earned me a Purple Heart. The war had just ended and I was still in my uniform for god’s sake! But on my way home, to the brink of death, they beat me like a common dog.The very same people whose freedoms and liberties I had fought and suffered to secure in the horrors of war … they beat me like a dog … merely because I wanted a drink of water.” He went on to say, “I had watched my best buddies tortured, murdered, and bodies blown to pieces. The French battlefields had literally been stained with my blood and fertilized with the rot of my loins.So at that moment, I truly felt as if I had fought on the wrong side. Then, and not until then, did I realize why God, time after time, had taken me to death’s door, then spared my life … to be a general in the war for human rights and personal dignity.” After the war, he earned a high school diploma at the age of 23, then a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree (both in chemistry) from Atlanta’s Morris Brown College and Atlanta University (present-day Clark Atlanta University). Williams was a member of Phi Beta Sigma fraternity.Williams’ birthday coincided with the anniversary of the death of one of that organization’s most prominent members, George Washington Carver. After college, Williams worked for the United States Department of Agriculture as a research scientist.Williams first joined the NAACP, but later became a leader in the SCLC along with Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy, James Bevel, Joseph Lowery, and Andrew Young, among many others. He played an important role in the demonstrations in St. Augustine, Florida, that some claim led to the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964.While organizing during the 1965 Selma Voting Rights Movement he also led the first attempt at a 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, and was tear gassed and beaten severely. On March 7, 1965 – a day that would become known as “Bloody Sunday” – Williams and fellow activist John Lewis led over 600 marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama.At the end of the bridge, they were met by Alabama State Troopers who ordered them to disperse. When the marchers stopped to pray, the police discharged tear gas and mounted troopers charged the demonstrators, beating them with night sticks. Repercussions from the “Bloody Sunday” attempt led to the other great legislative accomplishment of the movement, the Voting Rights Act of 1965.After leaving the SCLC, Williams played an active role in supporting strikes in the Atlanta, Georgia, area by black workers who had first been hired because of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.In the 1966 gubernatorial race, Williams opposed both the Democratic nominee, segregationist Lester Maddox, and the Republican choice, U.S. Representative Howard Callaway. He challenged Callaway on myriad issues relating to civil rights, minimum wage, federal aid to education, urban renewal, and indigent medical care.Williams claimed that Callaway had purchased the endorsement of the Atlanta Journal. Ultimately, after a general election deadlock, Maddox was elected governor by the state legislature.In 1972, Williams ran in the Democratic primary for the U.S. Senate seat formerly held by the late Richard Russell, Jr. He polled 46,153 votes (6.4 percent). The nomination and the election went to fellow Democrat Sam Nunn. In 1974, Williams was elected to the Georgia Senate where he served five terms as a Democrat, until 1984.In 1985 he was elected to the Atlanta City Council, serving for five years, until his election in 1989 when he ran for Mayor of Atlanta but lost to Maynard Jackson. That same year Williams successfully campaigned for a seat on the DeKalb County, Georgia County Commission which he held until 1994.Williams supported former Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter for president in 1976, but surprised many black civil rights figures in 1980 by joining Ralph Abernathy and Charles Evers in endorsing Ronald Reagan. By 1984, however, he had soured on Reagan’s policies, and returned to the Democrats to support Walter F. Mondale.On January 17, 1987, Williams led a “March Against Fear and Intimidation” in Forsyth County, Georgia, which at the time (before becoming a major exurb of northern metro Atlanta) had no non-white residents.The ninety marchers were assaulted with stones and other objects by several hundred counter-demonstrators led by the Nationalist Movement and Ku Klux Klan. The following week 20,000, including senior civil rights leaders and government officials marched. Forsyth County began to slowly integrate in the following years with the expansion of the Atlanta suburbs. In 1971, Hosea Williams founded a non-profit foundation, Hosea Feed the Hungry and Homeless, widely known in Atlanta for providing hot meals, haircuts, clothing, and other services for the needy on Thanksgiving, Christmas, Martin Luther King Jr. Day and Easter Sunday each year. Williams’ daughter Elizabeth Omilami serves as head of the foundation.In 1974, Williams organized the International Wrestling League (IWL), based in Atlanta, with Thunderbolt Patterson serving as president. Among other entrepreneurial endeavors, he founded Hosea Williams Bail Bonds Inc, a bail bond agency located in Decatur, Ga.In early 1951, Williams married Juanita Terry (1925–2000). Together, Williams and Terry had eight children. Four sons: Hosea L. Williams, II (1955–1998), Andre Williams, Torrey Williams, and Hyron Williams, and four daughters: Barbara Williams–Emerson, Elizabeth Williams–Omilami, Yolanda Williams–Favors, and Jaunita Collier. Williams died at Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta, after a three-year battle with cancer on November 16, 2000.Funeral services were held at the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, where close friend Martin Luther King Jr., was once the co-pastor. Williams was preceded in death by his wife three months prior and by his son Hosea II two years earlier. Williams is interred at Lincoln Cemetery.Boulevard Drive in the southeastern area of Atlanta was renamed Hosea L Williams Drive shortly before Williams died. Hosea Williams Drive runs by the site of his former home in the East Lake neighborhood at the intersection of Hosea L. Williams Drive and East Lake Drive.Hosea L. Williams Papers are housed at Auburn Avenue Research Library On African American Culture and History in Atlanta. His daughter Elisabeth Omilami also maintains a traveling exhibit of valuable civil rights memorabilia. Williams was portrayed by Wendell Pierce in the 2014 film Selma. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF– Today’s American Champion was an American actor known for numerous film roles, as well as starring in the NBC television series Homicide: Life on the Street (1993–1999) as Lieutenant Al Giardello.

GM – FBF– Today’s American Champion was an American actor known for numerous film roles, as well as starring in the NBC television series Homicide: Life on the Street (1993–1999) as Lieutenant Al Giardello. His films include the science-fiction/horror film Alien (1979), and the Arnold Schwarzenegger science-fiction/action film The Running Man (1987). He portrayed the main villain Dr. Kananga/Mr. Big in the James Bond movie Live and Let Die (1973). He appeared opposite Robert De Niro in the comedy thriller Midnight Run (1988) as FBI Agent Alonzo Mosley.Today in our History – November 15, 1939 – Yaphet Frederick Kotto is born.Kotto was born in New York City. His mother was Gladys Marie, an American nurse and U.S. Army officer of Panamanian and West Indian descent. His father was Avraham Kotto (according to his son, originally named Njoki Manga Bell), a businessman from Cameroon who emigrated to the United States in the 1920s. The couple separated when Kotto was a child, and he was raised by his maternal grandparents. His father was born Jewish and his mother converted to Judaism.By the age of sixteen, Kotto was studying acting at the Actors Mobile Theater Studio, and at 19, he made his professional acting debut in Othello. He was a member of the Actors Studio in New York. Kotto got his start in acting on Broadway, where he appeared in The Great White Hope, among other productions.His film debut was in 1963, aged 23, in an uncredited role in 4 For Texas. He performed in Michael Roemer’s Nothing But a Man (1964) and played a supporting role in the caper film The Thomas Crown Affair (1968). He played John Auston, a confused Marine Lance Corporal, in the 1968 episode, “King of the Hill”, on the first season of Hawaii Five-O.In 1967 he released a single, “Have You Ever Seen The Blues” / “Have You Dug His Scene” (Chisa Records, CH006).In 1973 he landed the role of the James Bond villain Mr. Big in Live and Let Die, as well as roles in Across 110th Street and Truck Turner. Kotto portrayed Idi Amin in the 1977 television film Raid on Entebbe. He starred as an auto worker in the 1978 film Blue Collar.The following year he played Parker in the sci-fi–horror film Alien. He followed with a supporting role in the 1980 prison drama Brubaker. In 1983, he guest-starred as mobster Charlie “East Side Charlie” Struthers in The A-Team episode “The Out-of-Towners”. In 1987, he appeared in the futuristic sci-fi movie The Running Man, and in 1988, in the action-comedy Midnight Run, in which he portrayed Alonzo Moseley, an FBI agent.A memo from Paramount indicates that Kotto was among those being considered for Jean-Luc Picard in Star Trek: The Next Generation, a role which eventually went to Patrick Stewart. Kotto was cast as a religious man living in the southwestern desert country in the 1967 episode, “A Man Called Abraham”, on the syndicated anthology series, Death Valley Days, hosted by Robert Taylor. In the story line, Abraham convinces a killer named Cassidy (Rayford Barnes) that Cassidy can change his heart despite past crimes. When Cassidy is sent to the gallows, Abraham provides spiritual solace. Bing Russell also appeared in this segment.Kotto retired from film acting in the mid-1990s, though had one final film role in Witless Protection (2008). However, he continued to take on television roles. Kotto portrayed Lieutenant Al Giardello in the long-running television series Homicide: Life on the Street.He has written the book Royalty and also wrote scripts for Homicide. In 2014, he voiced “Parker” for the video game Alien: Isolation, reprising the role he played in the movie Alien in 1979.Kotto’s first marriage was to a German immigrant, Rita Ingrid Dittman, whom he married in 1959. They had three children together before divorcing in 1976. Later, Kotto married Toni Pettyjohn, and they also had three children together, before divorcing in 1989. Kotto married his third wife, Tessie Sinahon, who is from the Philippines, in 1998.Kotto said his father “installed Judaism” in him.In 2000, he was living in Marmora, Ontario, Canada.He died on March 15, 2021, at the age of 81 near Manila, Philippines. No cause of death was given. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

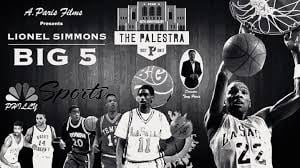

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American former professional basketball player.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American former professional basketball player.Today in our History – November 14, 1968 – Lionel James “L-Train” Simmons is born.Simmons led South Philadelphia High School to a Philadelphia Public League boys’ championship in 1986, getting an MVP award in the process. He was inducted into the Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame in 2008. Simmons was a 6’7″ small forward from La Salle University, where he won the Naismith College Player of the Year and John R. Wooden Award as a senior. Simmons is fourth in all-time NCAA career points with 3,217 and trails only Pete Maravich, Freeman Williams and Chris Clemons. Simmons became the first player in NCAA history to score more than 3,000 points and pull down more than 1,100 rebounds. He holds the NCAA Basketball record for most consecutive games scoring in double figures with 115. He led the Explorers to three straight NCAA Tournament appearances (1988–90). Simmons was Player of the Year in the Metro Atlantic Athletic Conference for three years. He was a four-time First Team All Big 5 selection and won the Robert V. Geasey Trophy as Big 5 MVP three times. During his career, the Explorers had a 100-31 record. Simmons was inducted into the La Salle University Hall of Athletes in 1995. Simmons was inducted into the Big 5 Hall of Fame in 1996. Simmons was selected by the Sacramento Kings with the seventh pick of the 1990 NBA draft. On March 23, 1991, Simmons scored a career-high 42 points in a 95-100 loss to the Phoenix Suns. He was the runner-up to Derrick Coleman for the 1991 NBA Rookie of the Year Award. Simmons was NBA Player of the Week the week after the All-Star break during his rookie season.He played seven seasons for the Kings, scoring 5,833 career points until prematurely retiring in 1997 due to chronic injuries. He managed to earn more than $21 million in an NBA career that lasted seven seasons. Reserach more about this American Champion and share it with your babies. Male it a champion day!

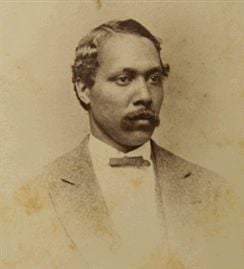

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African American who was appointed United States Ambassador to Haiti in 1869.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African American who was appointed United States Ambassador to Haiti in 1869. He was the first African-American diplomat and the fourth U.S. ambassador to Haiti since the two countries established relations in 1862.His asset was appointed as new leaders emerged among free African Americans after the American Civil War. An educator, abolitionist, and civil rights activist, Bassett was the U.S. diplomatic envoy in 1869 to Haiti, the “Black Republic” of the Western Hemisphere. Through eight years of bloody civil war and coups d’état there, he served in one of the most crucial, but difficult postings of his time. Haiti was of strategic importance in the Caribbean basin for its shipping lanes and as a naval coaling station.Today in our History November 13, 1908 – Prior to his death, Ebenezer D. Bassett returned to live in Philadelphia, where his daughter Charlotte also taught at the ICY. Ebenezer D. Bassett was appointed U.S. Minister Resident to Haiti in 1869, making him the first African American diplomat. For eight years, the educator, abolitionist, and black rights activist oversaw bilateral relations through bloody civil warfare and coups d’état on the island of Hispaniola. Bassett served with distinction, courage, and integrity in one of the most crucial, but difficult postings of his time.Born in Connecticut on October 16, 1833, Ebenezer D. Bassett was the second child of Eben Tobias and Susan Gregory. In a rarity during the mid-1800s, Bassett attended college, becoming the first black student to integrate the Connecticut Normal School in 1853. He then taught in New Haven, befriending the legendary abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Later, he became the principal of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania’s Institute for Colored Youth (ICY).During the Civil War, Bassett became one of the city’s leading voices into the cause behind that conflict, the liberation of four million black slaves and helped recruit African American soldiers for the Union Army. In nominating Bassett to become Minister Resident to Haiti, President Ulysses S. Grant made him one of the highest ranking black members of the United States government.During his tenure the American Minister Resident also dealt with cases of citizen commercial claims, diplomatic immunity for his consular and commercial agents, hurricanes, fires, and numerous tropical diseases.The case that posed the greatest challenge to him, however, was Haitian political refugee General Pierre Boisrond Canal. The general was among the band of young leaders who had successfully ousted the former President Sylvan Salnave from power in 1869. By the time of the subsequent Michel Domingue regime in the mid 1870s Canal had retired to his home outside the capital. Domingue, the new Haitian President, however, brutally hunted down any perceived threat to his power including Canal.General Canal came to Bassett and requested political asylum. A standoff resulted, with Bassett’s home surrounded by over a thousand of Domingue’s soldiers. Finally, after five-month siege of his residence, Bassett negotiated Canal’s safe release for exile in Jamaica.Upon the end of the Grant Administration in 1877, Bassett submitted his resignation as was customary with a change of hands in government. When he returned to the United States, he spent an additional ten years as the Consul General for Haiti in New York City, New York. Prior to this death on November 13, 1908, he returned to live in Philadelphia, where his daughter Charlotte also taught at the ICY. Bassett was 75 at the time of his death.Ebenezer D. Bassett was a role model not simply for his symbolic importance as the first African American diplomat. His concern for human rights, his heroism, and courage in the face of pressure from Haitians, as well as his own capital, place him in the annals of great American diplomats. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a Bahamian-born American entertainer, one of the pre-eminent entertainers of the Vaudeville era and one of the most popular comedians for all audiences of his time

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a Bahamian-born American entertainer, one of the pre-eminent entertainers of the Vaudeville era and one of the most popular comedians for all audiences of his time. He is credited as being the first black man to have the leading role in a film: Darktown Jubilee in 1914.He was by far the best-selling black recording artist before 1920. In 1918, the New York Dramatic Mirror called Williams “one of the great comedians of the world.”Williams was a key figure in the development of African-American entertainment. In an age when racial inequality and stereotyping were commonplace, he became the first black American to take a lead role on the Broadway stage, and did much to push back racial barriers during his three-decade-long career. Fellow vaudevillian W. C. Fields, who appeared in productions with Williams, described him as “the funniest man I ever saw—and the saddest man I ever knew.”Today in our History – November 12, 1874 – Bert Williams (November 12, 1874 – March 4, 1922) was born.Egbert “Bert” Austin Williams was one of the greatest entertainers in America’s history. Born in the Bahamas on November 12, 1874, he came to the United States permanently in 1885.Williams met George Walker in San Francisco in 1893 and the two formed what became the most successful comedy team of their time. After appearing on Broadway in Victor Herbert’s The Gold Bug (1896), Williams and Walker created pioneering vaudeville shows and full musical theater productions, including Senegambian Carnival (1897), The Policy Players (1899), The Sons of Ham (1900), their biggest hit, In Dahomey (1902)–which also played in London the following year, Abyssinia (1906), and Bandana Land (1907).When Walker retired in 1908 due to illness, Williams starred in Mr. Load of Koal (1909)–the last black musical on Broadway for more than ten years. Unable to continue producing shows without Walker, Williams signed on with the Ziegfeld Follies in 1910–the only black performer in this famous review.He explained this controversial move saying, “… colored show business is at a low ebb just now … it was far better to have joined a large white show than to have starred in a colored show, considering conditions.” Williams stayed with the Follies through 1919, after which he appeared with Eddie Cantor in Broadway Brevities (1920) and Under the Bamboo Tree (1921-22). While on tour with the latter show, his failing health caught up with him and he contracted pneumonia. Williams died in New York City on March 4, 1922.Williams was also one of the most prolific black performers on recordings, making around 80 recordings from 1901-22. Indeed, his first recording sessions with George Walker for the Victor Company in 1901 are considered the first recordings by black performers for a major recording company. Williams signed with Columbia in 1906 and the majority of his recordings were with that company, including what became his signature number, “Nobody,” with words written by Alex Rogers. Research more about this great American Champion snd share it with you babies, Make it a champion day!