GM – FBF – Today I would like to share with you a story about

our government spying, paying off, infiltrating and disbanding individuals or

groups that they deemed as a threat to the American cause. This group operated

unchecked by the media or congress for decades. If you never heard of this ask

one of your elders or research it for yourself. Enjoy!

Remember – “Prevent the RISE OF A “MESSIAH” who could

unify, and electrify, the militant Black Nationalist movement. Malcolm X might

have been such a “messiah;” he is the martyr of the movement today.

Martin Luther King, Stokely Carmichael and Elijah Muhammed all aspire to this

position. Elijah Muhammed is less of a threat because of his age. King could be

a very real contender for this position should he abandon his supposed

“obedience” to “white, liberal doctrines” (nonviolence) and

embrace Black Nationalism. Carmichael has the necessary charisma to be a real

threat in this way.” – J. Edgar Hoover – FBI Director

Today in our History – August 25, 1956 -Centralized operations

under COINTELPRO officially began on August 25, 1956 with a program designed to

“increase factionalism, cause disruption and win defections” inside

the Communist Party USA (CPUSA).

COINTELPRO (Portmanteau derived from COunter INTELligence PROgram)

(1956–1971) was a series of covert, and at times illegal, projects conducted by

the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) aimed at surveilling,

infiltrating, discrediting, and disrupting domestic political organizations.

FBI records show that COINTELPRO resources targeted groups and individuals that

the FBI deemed subversive, including the Communist Party USA, anti-Vietnam War

organizers, activists of the civil rights movement or Black Power movement

(e.g. Martin Luther King Jr., Nation of Islam, and the Black Panther Party),

feminist organizations, independence movements (such as Puerto Rican

independence groups like the Young Lords), and a variety of organizations that

were part of the broader New Left.

The program also targeted white supremacist groups including the

Ku Klux Klan and nationalist groups including Irish Republicans and Cuban

exiles. The FBI also financed, armed, and controlled an extreme right-wing

group of former Minutemen, transforming it into a group called the Secret Army

Organization that targeted groups, activists, and leaders involved in the

Anti-War Movement, using both intimidation and violent acts.

Centralized operations under COINTELPRO officially began on

August 25, 1956 with a program designed to “increase factionalism, cause

disruption and win defections” inside the Communist Party USA (CPUSA).

Tactics included anonymous phone calls, IRS audits, and the creation of

documents that would divide the American communist organization internally. An

October 1956 memo from Hoover reclassified the FBI’s ongoing surveillance of

black leaders, including it within COINTELPRO, with the justification that the

movement was infiltrated by communists. In 1956, Hoover sent an open letter

denouncing Dr. T.R.M. Howard, a civil rights leader, surgeon, and wealthy

entrepreneur in Mississippi who had criticized FBI inaction in solving recent

murders of George W. Lee, Emmett Till, and other black people in the South.[30]

When the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), an African-American

civil rights organization, was founded in 1957, the FBI began to monitor and

target the group almost immediately, focusing particularly on Bayard Rustin,

Stanley Levison, and eventually Martin Luther King Jr.

The “suicide letter”, that the FBI mailed anonymously

to Martin Luther King Jr. in an attempt to convince him to commit suicide.

After the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Hoover

singled out King as a major target for COINTELPRO. Under pressure from Hoover

to focus on King, Sullivan wrote:

In the light of King’s powerful demagogic speech. … We must mark him now if

we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this

nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro, and national

security.

Soon after, the FBI was systematically bugging King’s home and his hotel rooms,

as they were now aware that King was growing in stature daily as the leader

among leaders of the civil rights movement.

In the mid-1960s, King began publicly criticizing the Bureau for

giving insufficient attention to the use of terrorism by white supremacists.

Hoover responded by publicly calling King the most “notorious liar”

in the United States. IN his 1991 memoir, Washington Post journalist Carl Rowan

asserted that the FBI had sent at least one anonymous letter to King

encouraging him to commit suicide. Historian Taylor Branch documents an

anonymous November 21, 1964 “suicide package” sent by the FBI that

contained audio recordings, which were obtained through tapping King’s phone and

placing bugs throughout various hotel rooms over the past two years was created

two days after the announcement of King’s impending Nobel Peace Prize.

The tape, which was prepared by FBI audio technician John

Matter documented a series of King’s sexual indiscretions combined with a

letter telling him “There is only one way out for you. You better take it

before your filthy, abnormal, fraudulent self is bared to the nation”.

King was subsequently informed that the audio would be released to the media if

he did not acquiesce and commit suicide prior to accepting his Nobel Peace

Award. When King refused to satisfy their coercion tactics, FBI Associate

Director, Cartha D. DeLoach, commenced a media campaign offering the

surveillance transcript to various news organizations including, Newsweek and

Newsday. And even by 1969, as has been noted elsewhere, “[FBI] efforts to

‘expose’ Martin Luther King Jr. had not slackened even though King had been

dead for a year. [The Bureau] furnished ammunition to conservatives to attack

King’s memory, and…tried to block efforts to honor the slain leader.”

During the same period the program also targeted Malcolm X.

While an FBI spokesman has denied that the FBI was “directly”

involved in Malcolm’s murder, it is documented that the Bureau worked to

“widen the rift” between Malcolm and Elijah Muhammad through

infiltration and the “sparking of acrimonious debates within the

organization,” rumor-mongering, and other tactics designed to foster

internal disputes, which ultimately led to Malcolm’s assassination. The FBI

heavily infiltrated Malcolm’s Organization of Afro-American Unity in the final

months of his life. The Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Malcolm X by

Manning Marable asserts that most of the men who plotted Malcolm’s

assassination were never apprehended and that the full extent of the FBI’s

involvement in his death cannot be known.

Amidst the urban unrest of July–August 1967, the FBI began

“COINTELPRO–BLACK HATE”, which focused on King and the SCLC as well

as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Revolutionary

Action Movement (RAM), the Deacons for Defense and Justice, Congress of Racial

Equality (CORE), and the Nation of Islam. BLACK HATE established the Ghetto

Informant Program and instructed 23 FBI offices to “disrupt, misdirect,

discredit, or otherwise neutralize the activities of black nationalist hate

type organizations”.

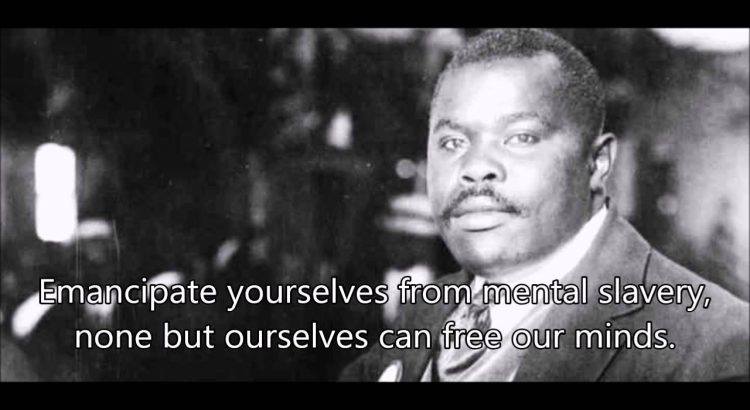

A March 1968 memo stated the program’s goal was to “prevent

the coalition of militant black nationalist groups”; to “Prevent the

RISE OF A ‘MESSIAH’ who could unify…the militant black nationalist

movement”; “to pinpoint potential troublemakers and neutralize them

before they exercise their potential for violence [against authorities].”;

to “Prevent militant black nationalist groups and leaders from gaining

RESPECTABILITY, by discrediting them to…both the responsible community and to

liberals who have vestiges of sympathy…”; and to “prevent the

long-range GROWTH of militant black organizations, especially among youth.”

Dr. King was said to have potential to be the “messiah” figure,

should he abandon nonviolence and integrationism, and Stokely Carmichael was

noted to have “the necessary charisma to be a real threat in this

way” as he was portrayed as someone who espoused a much more militant

vision of “black power.”

While the FBI was particularly concerned with leaders and

organizers, they did not limit their scope of target to the heads of

organizations. Individuals such as writers were also listed among the targets

of operations.

This program coincided with a broader federal effort to prepare

military responses for urban riots, and began increased collaboration between

the FBI, Central Intelligence Agency, National Security Agency, and the

Department of Defense. The CIA launched its own domestic espionage project in

1967 called Operation CHAOS. A particular target was the Poor People’s

Campaign, a national effort organized by King and the SCLC to occupy

Washington, D.C. The FBI monitored and disrupted the campaign on a national

level, while using targeted smear tactics locally to undermine support for the

march.[49] The Black Panther Party was another targeted organization, wherein

the FBI collaborated to destroy the party from the inside out.

Overall, COINTELPRO encompassed disruption and sabotage of the

Socialist Workers Party (1961), the Ku Klux Klan (1964), the Nation of Islam,

the Black Panther Party (1967), and the entire New Left social/political

movement, which included antiwar, community, and religious groups (1968). A later

investigation by the Senate’s Church Committee (see below) stated that

“COINTELPRO began in 1956, in part because of frustration with Supreme

Court rulings limiting the Government’s power to proceed overtly against

dissident groups …” Official congressional committees and several court

cases have concluded that COINTELPRO operations against communist and socialist

groups exceeded statutory limits on FBI activity and violated constitutional

guarantees of freedom of speech and association.

The program was successfully kept secret until 1971, when the

Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI burgled an FBI field office in

Media, Pennsylvania, took several dossiers, and exposed the program by passing

this material to news agencies.[51] The Fight of the Century between Muhammad

Ali and Joe Frazier provided cover for the activist group to successfully pull

off the burglary; Muhammad Ali was himself a COINTELPRO target due to his

involvement with the Nation of Islam and the anti-war movement. Many news organizations

initially refused to publish the information. Within the year, Director J.

Edgar Hoover declared that the centralized COINTELPRO was over, and that all

future counterintelligence operations would be handled on a case-by-case basis.

Additional documents were revealed in the course of separate

lawsuits filed against the FBI by NBC correspondent Carl Stern, the Socialist

Workers Party, and a number of other groups. In 1976 the Select Committee to

Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities of the

United States Senate, commonly referred to as the “Church Committee”

for its chairman, Senator Frank Church of Idaho, launched a major investigation

of the FBI and COINTELPRO. Many released documents have been partly, or

entirely, redacted.

The Final Report of the Select Committee castigated the conduct

of the intelligence community in its domestic operations (including COINTELPRO)

in no uncertain terms:

The Committee finds that the domestic activities of the intelligence community at

times violated specific statutory prohibitions and infringed the constitutional

rights of American citizens. The legal questions involved in intelligence

programs were often not considered. On other occasions, they were intentionally

disregarded in the belief that because the programs served the “national

security” the law did not apply. While intelligence officers on occasion

failed to disclose to their superiors programs which were illegal or of

questionable legality, the Committee finds that the most serious breaches of

duty were those of senior officials, who were responsible for controlling

intelligence activities and generally failed to assure compliance with the law.

Many of the techniques used would be intolerable in a democratic

society even if all of the targets had been involved in violent activity, but

COINTELPRO went far beyond that … the Bureau conducted a sophisticated

vigilante operation aimed squarely at preventing the exercise of First

Amendment rights of speech and association, on the theory that preventing the

growth of dangerous groups and the propagation of dangerous ideas would protect

the national security and deter violence.

The Church Committee

documented a history of the FBI exercising political repression as far back as

World War I, through the 1920s, when agents were charged with rounding up

“anarchists, communists, socialists, reformists and revolutionaries”

for deportation. The domestic operations were increased against political and

anti-war groups from 1936 through 1976. Research more about our government

working to keep Black groups, Individuals and entertainers from gaining power.

Share with your babies and make it a champion day!