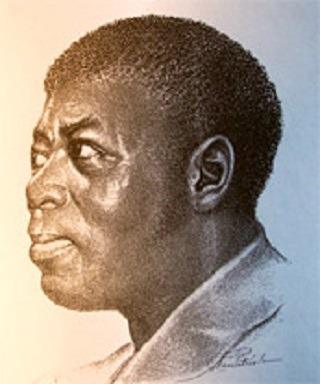

GM – FBF – Our story for today is about a person who was a black poet and 1761 became the first African-American writer to be published in the present-day United States. Additional poems and sermons were also published. Born into slavery, never was never emancipated. He was living in 1790 at the age of 79, and died by 1806. A devout Christian, he is considered to be one of the founders of African-American literature.

Remember – “If we should ever get to Heaven, we shall find nobody to reproach us for being black, or for being slaves.” – Jupiter Hammon

Today in our History – December 25, 1760 – Jupiter Hammon

Publishes “An Evening Thought, by Christ, with Penitential Cries”

Born in 1711 in a house now known as Lloyd Manor in Lloyd Harbor, NY – per a

Town of Huntington, NY historical marker dated 1990 – Hammon was held by four

generations of the Lloyd family of Queens on Long Island, New York. His parents

were both slaves held by the Lloyds. His mother and father were part of the

first shipment of slaves to the Lloyd’s estate in 1687. Unlike most slaves, his

father, named Obadiah, had learned to read and write.

The Lloyds encouraged Hammon to attend school, where he also learned to read and write. Jupiter attended school with the Lloyd children. As an adult, he worked for them as a domestic servant, clerk, farmhand, and artisan in the Lloyd family business. He worked alongside Henry Lloyd (the father) in negotiating deals. Henry Lloyd said that Jupiter was so efficient in trade deals because he would quickly get the job done. He became a fervent Christian, as were the Lloyds.

His first published poem, “An Evening Thought. Salvation by

Christ with Penitential Cries: Composed by Jupiter Hammon, a Negro belonging to

Mr. Lloyd of Queen’s Village, on Long Island, the 25th of December, 1760,”

appeared as a broadside in 1761.

Eighteen years passed before his second work appeared in print, “An

Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley.” Hammon wrote this poem while Lloyd had

temporarily moved himself and the slaves he owned to Hartford, Connecticut,

during the Revolutionary War.

Hammon saw Wheatley as having succumbed to pagan influences in her writing, and so the “Address” consisted of twenty-one rhyming quatrains, each accompanied by a related Bible verse, that he thought would compel Wheatley to return to a Christian path in life. He would later publish two other poems and three sermon essays.

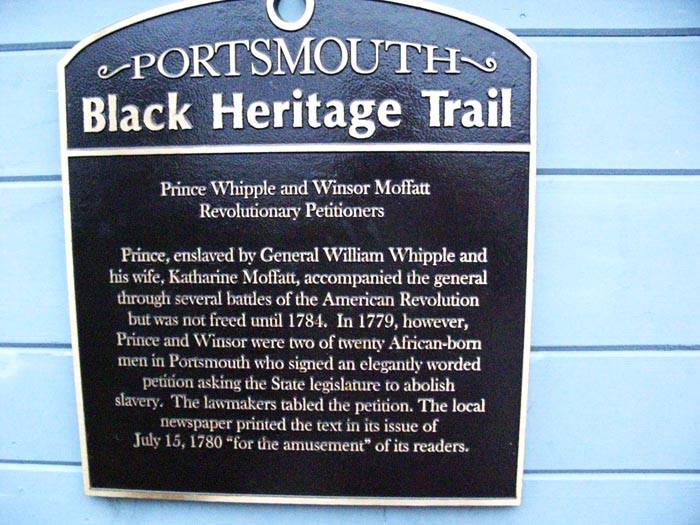

Although not emancipated, Hammon participated in new Revolutionary War groups such as the Spartan Project of the African Society of New York City. At the inaugural meeting of the African Society on September 24, 1786, he delivered his “Address to the Negroes of the State of New-York”, also known as the “Hammon Address.” He was seventy-six years old and had spent his lifetime in slavery. He said, “If we should ever get to Heaven, we shall find nobody to reproach us for being black, or for being slaves.” He also said that, while he personally had no wish to be free, he did wish others, especially “the young negroes, were free.”

The speech draws heavily on Christian motifs and theology. For example, Hammon said that Black people should maintain their high moral standards because being slaves on Earth had already secured their place in heaven. He promoted gradual emancipation as a way to end slavery.[5] Scholars think perhaps Hammon supported this plan because he believed that immediate emancipation of all slaves would be difficult to achieve. New York Quakers, who supported abolition of slavery, published his speech. It was reprinted by several abolitionist groups, including the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery.

In the two decades after the Revolutionary War and creation of the new government, northern states generally abolished slavery. In the Upper South, so many slaveholders manumitted slaves that the proportion of free blacks among African Americans increased from less than one percent in 1790 to more than 10 percent by 1810. In the United States as a whole, by 1810 the number of free blacks was 186,446, or 13.5 percent of all African Americans.

Hammon’s speech and his poetry are often included in anthologies of notable African-American and early American writing. He was the first known African American to publish literature within the present-day United States (in 1773, Phillis Wheatley, also an American slave, had her collection of poems first published in London, England). His death was not recorded. He is thought to have died sometime around 1806 and is buried in an unmarked grave somewhere on the Lloyd property.

While researching the writer, UT Arlington doctoral student Julie McCown stumbled upon a previously unknown poem written by Hammon stored in the Manuscripts and Archives library at Yale University. The poem, dated 1786, is described by McCown as a ‘shifting point’ in Jupiter Hammon’s worldview surrounding slavery. Research more about Black writers during the revolutionary war and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!