GM – FBF – Today, I want to share a story with you, Recy Corbitt Taylor was a 24-year-old sharecropper who was gang-raped in September 1944 in Abbeville, Alabama. Her attackers were local white teenagers who were never indicted, despite the efforts of Rosa Parks (then an investigator for the NAACP), a nationwide campaign that brought attention to this miscarriage of justice and even a confession from one assailant. The case received renewed public attention with a 2010 book, a 2017 documentary and when Taylor was mentioned by Oprah Winfrey during her acceptance speech for the Cecil B. DeMille Award at the 2018 Golden Globes. The movie comes on your stations next week July 2nd. Please watch and share with your babies.

Remember – “The people who done this to me … they can’t do no apologizing. Most of them is gone.” – Recy Taylor

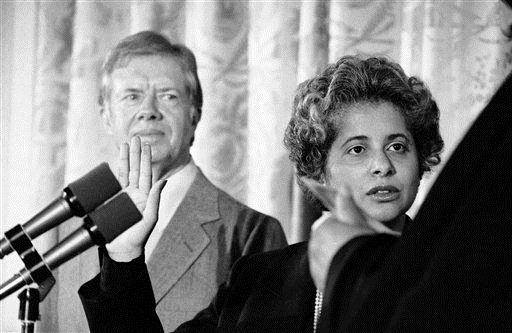

Today in our History – June 30, 2010 – Taylor’s case, despite the involvement of Rosa Parks and the NAACP, faded from public attention as the 1940s progressed. But with the publication of At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance — a New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power (June 30, 2010), historian Danielle L. McGuire brought fresh attention to Taylor’s ordeal. McGuire was able to unearth primary documents and linked activist work on Taylor’s case to the Civil Rights Movement.

Director Nancy Buirski read McGuire’s book, which inspired her to make the documentary The Rape of Recy Taylor (2017). The movie contains interviews with Taylor, her brother and sister, as well as talks with family members of the accused rapists, to shine a light on both the attack and what caused such a miscarriage of justice.

Taylor’s attack began on the night of September 3, 1944, as she was walking home from a church revival meeting with two companions. A car that had been following the threesome stopped, and the occupants — seven white teenagers armed with guns and knives — accused Taylor of an attack that had taken place earlier in the day. Held at gunpoint, Taylor had no choice but to get into the car.

Instead of taking her to the police station, as they’d said, the teens took Taylor to a secluded area. Though she begged for mercy, they forced her to undress, and at least six raped her for several hours (one kidnapper would later say he did not participate in the sexual assault because he knew Taylor). Taylor said they threatened to kill her if she spoke out about what had happened before leaving her blindfolded at the side of a lonely road.

Taylor’s father, who’d been informed of the abduction, found her making her way home. Despite the warning, Taylor related details of the attack to her father, husband and the sheriff. She couldn’t name her rapists, but told the sheriff the car she’d been in was a green Chevrolet; he recognized the vehicle and brought Hugo Wilson to Taylor, who identified him as one of her assailants.

Wilson named the others who’d been with him: Herbert Lovett, Dillard York, Luther Lee, Willie Joe Culpepper, Robert Gamble and Billy Howerton (Howerton was the one who said he didn’t take part in the rape). However, Wilson also claimed that they had paid Taylor to have sex. (Though Taylor was known to be a diligent worker and dedicated churchgoer, the sheriff and others would eventually make false claims that Taylor had been jailed and had a history of venereal disease.)

Taylor’s house was soon firebombed, so she, her husband and daughter had to move in with her father and younger siblings. To protect his family, Taylor’s father maintained an armed vigil at night and slept during the day.

Rosa Parks (a victim of attempted rape herself who documented such crimes against black women) came from the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP to talk with Taylor. The official investigation didn’t even include a lineup for Taylor to try to identify her attackers. The grand jury met in early October, but only Taylor and her associates testified, and no indictments were issued.

Parks and other activists formed the “Committee for Equal Justice for Mrs. Recy Taylor” to bring attention to the case. There were committee branches in multiple states, and well-known people such as W.E.B. DuBois, Mary Church Terrell and Langston Hughes got involved. Alabama Governor Chauncey Sparks received numerous telegrams, postcards and petitions calling for justice.

An article in the Chicago Defender highlighted how Taylor and her husband had been offered money to “forget” the rape. And some writers drew attention to the fact that America was fighting fascism abroad during World War II while taking no steps to ensure that every citizen at home would be treated fairly and equally under the law.

Governor Sparks did order a private investigation; Willie Joe Culpepper even corroborated Taylor’s version of her ordeal, admitting, “She was crying and asking us to let her go home to her husband and baby.” Yet a second grand jury still failed to provide indictments in February 1945 (like the first, the members were all white and male, and some had family connections to the accused).

Sadly, after Taylor’s attack there was a consistent supply of new crimes — from black women who were sexually assaulted to black men lynched following unfounded accusations of sexual crimes — to draw activist attention, and her case faded from public view.

With help from Rosa Parks, Taylor spent a few months in Montgomery before returning to an area filled with people who’d contributed to her case passing without justice. Taylor ended up moving to Florida in 1965, where she found work picking oranges. She remained in Florida until her health worsened and relatives brought her back to Abbeville.

Through the years, the memory

of her assault lingered for Taylor. But she was thankful she hadn’t been

killed, telling NPR’s Michel Martin in 2011, “They was talking about

killing me … but the Lord is just with me that night.”

Recy Corbitt Taylor (1919-2017). Make it a champion day!