GM – FBF – It is incumbent upon all of us to build communities with the educational opportunities and support systems in place to help our youth become successful adults.

Remember – Is Georgia going to go down in history as another Alabama or Missassippi or are you going to do the right thing. – Charlayne Hunter

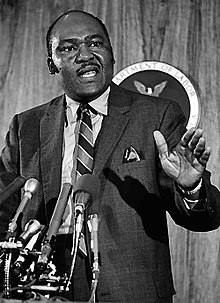

Today in our History – January 11, 1961 – The 1961 desegregation of the University of Georgia by Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter is considered a defining moment in civil rights history, leading to the desegregation of other institutions of higher education in Georgia and throughout the Deep South. When the two students walked on to North Campus on January 9 to register for classes, the event marked the culmination of a legal battle that had begun a decade earlier when Horace Ward unsuccessfully sought admission to the law school. Holmes and Hunter were represented by a legal team headed by Atlanta civil rights attorney Donald Hollowell and Constance Baker-Motley of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. They were joined by Ward, who had earned his law degree at Northwestern, and by Vernon Jordan, a young Atlantan who had just graduated from Howard University Law School.

Holmes and Hunter had both attended all-black Turner High School in Atlanta where Holmes had been valedictorian, senior class president, and co-captain of the football team. Hunter had finished third in her graduating class, had edited the school paper, and had been crowned Miss Turner. Nevertheless, for a year and a half university officials gave a variety of reasons for denying their applications. While the court fight was being waged, the two students started their college careers at other institutions: Holmes at Morehouse and Hunter at integrated Wayne State University in Detroit.

On January 6, 1961, federal judge William Bootle handed down his finding that “the two plaintiffs are fully qualified for immediate admission” and “would already have been admitted had it not been for their race and color.”

On Monday, January 9, as the two students arrived on North Campus, they were met by a crowd of reporters and fellow students, the latter chanting “Two-four-six-eight! We don’t want to integrate!” Still, relative calm prevailed until the third evening after their arrival, when a mob of students descended on Myers Hall, where Hunter resided. The crowd hurled bricks and bottles before finally being dispersed by Athens police, who arrived with tear gas, and Dean of Men William Tate, who waded into the crowd demanding student IDs.

Later that night, Holmes and Hunter were escorted back to Atlanta by state troopers. They were informed by Dean of Students J. A. Williams that he was withdrawing them from UGA “in the interest of your personal safety and for the safety and welfare of more than 7,000 other students at the University of Georgia.” The riot and the suspension decision sparked an outcry, and more than 400 faculty members immediately signed a resolution calling for the return of Holmes and Hunter to campus. Within days, a new court order brought them back. Research more about this event in our history and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!