GM – FBF – Our story today may be new to some but ask your grandparents who know of his pictures of famous black people or landscapes or maybe you watched some of his movies on television and didn’t know that was his work. If you have forgotten him, enjoy!

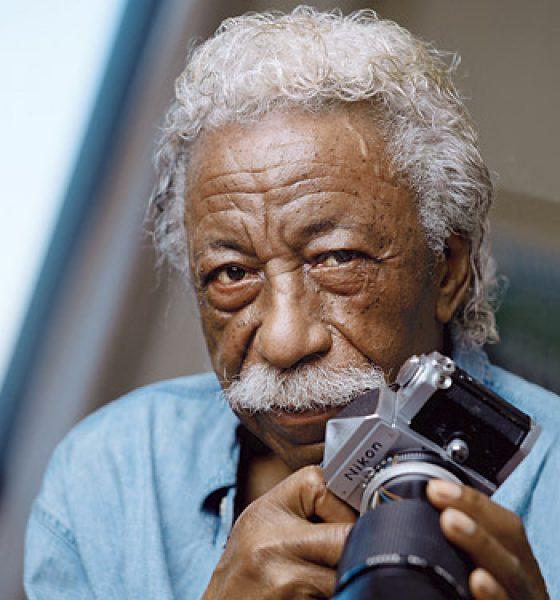

Remember – “At first I wasn’t sure that I had the talent, but I did know I had a fear of failure, and that fear compelled me to fight off anything that might abet it.” Gordon Parks

Today in our History – November 30, 1912 – Gordon Parks was born. He was a prolific, world-renowned photographer, writer, composer and filmmaker known for his work on projects like Shaft and The Learning Tree.

Born on November 30, 1912, in Fort Scott, Kansas, Gordon Parks was a self-taught artist who became the first African-American photographer for Life and Vogue magazines. He also pursued movie directing and screenwriting, working at the helm of the films The Learning Tree, based on a novel he wrote, and Shaft. Parks has published several memoirs and retrospectives as well, including A Choice of Weapons.

Gordon Roger Alexander Buchanan Parks was born on November 30,

1912, in Fort Scott, Kansas. His father, Jackson Parks, was a vegetable farmer,

and the family lived modestly.

Parks faced aggressive discrimination as a child. He attended a segregated

elementary school and was not allowed to participate in activities at his high

school because of his race.

The teachers actively discouraged African-American students from seeking higher education. After the death of his mother, Sarah, when he was 14, Parks left home. He lived with relatives for a short time before setting off on his own, taking whatever odd jobs he could find.

Parks purchased his first camera at the age of 25 after viewing photographs of migrant workers in a magazine. His early fashion photographs caught the attention of Marva Louis, wife of the boxing champion Joe Louis, who encouraged Parks to move to a larger city. Parks and his wife, Sally, relocated to Chicago in 1940.

Parks began to explore subjects beyond portraits and fashion photographs in Chicago. He became interested in the low-income black neighborhoods of Chicago’s South Side. In 1941, Parks won a photography fellowship with the Farm Security Administration for his images of the inner city. Parks created some of his most enduring photographs during this fellowship, including “American Gothic, Washington, D.C.,” picturing a member of the FSA cleaning crew in front of an American flag.

After the FSA disbanded, Parks continued to take photographs for the Office of War Information and the Standard Oil Photography Project. He also became a freelance photographer for Vogue. Parks worked for Vogue for a number of years, developing a distinctive style that emphasized the look of models and garments in motion, rather than in static poses.

Relocating to Harlem, Parks continued to document city images and characters while working in the fashion industry. His 1948 photographic essay on a Harlem gang leader won Parks a position as a staff photographer for LIFE magazine, the nation’s highest-circulation photographic publication. Parks held this position for 20 years, producing photographs on subjects including fashion, sports and entertainment as well as poverty and racial segregation. He was also took portraits of African-American leaders, including Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael and Muhammad Ali.

Parks launched a writing career during this period, beginning with his 1962 autobiographical novel, The Learning Tree. He would publish a number of books throughout his lifetime, including a memoir, several works of fiction and volumes on photographic technique.

In 1969, Parks became the first African American to direct a major Hollywood movie, the film adaptation of The Learning Tree. He wrote the screenplay and composed the score for the film.

Parks’s next film, Shaft, was one of the biggest box-office hits of 1971. Starring Richard Roundtree as detective John Shaft, the movie inspired a genre of films known as blaxploitation. Isaac Hayes won an Academy Award for the movie’s theme song. Parks also directed a 1972 sequel, Shaft’s Big Score. His attempt to deviate from the Shaft series, with the 1976 Leadbelly, was unsuccessful. Following this failure, Parks continued to make films for television, but did not return to Hollywood.

Parks was married and divorced three times. He and Sally Alvis married in 1933, divorcing in 1961. Parks remarried in 1962, to Elizabeth Campbell. The couple divorced in 1973, at which time Parks married Genevieve Young. Young had met Parks in 1962 when she was assigned to be the editor of his book The Learning Tree. They divorced in 1979. Parks was also romantically linked to railroad heiress Gloria Vanderbilt for a period of years.

Parks had four children. His oldest son, filmmaker Gordon Parks Jr., died in a 1979 plane crash in Kenya.

The 93-year-old Gordon Parks died of cancer on March 7, 2006, in New York City. He is buried in his hometown of Fort Scott, Kansas. Today, Parks is remembered for his pioneering work in the field of photography, which has been an inspiration to many. The famed photographer once said, “People in millenniums ahead will know what we were like in the 1930’s and the thing that, the important major things that shaped our history at that time. This is as important for historic reasons as any other.” Research more about this great American hero and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!