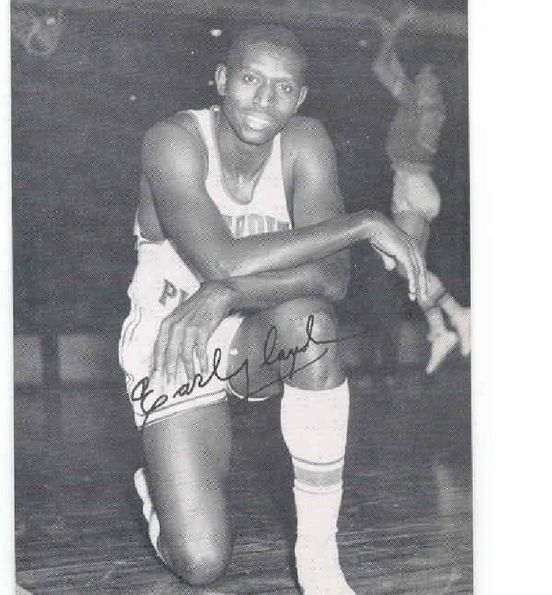

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American professional basketball player and coach. He was the first African American player to play a game in the National Basketball Association (NBA).An All–American player at West Virginia State University, he helped lead West Virginia State to an undefeated season in 1948. As a professional, Lloyd helped lead the Syracuse Nationals to the 1955 NBA Championship. He was inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in 2003.Today in our History – October 31, 1950 – Earl Francis Lloyd (April 3, 1928 – February 26, 2015) Played in a NBA Pro Game.Earl Lloyd was born in Alexandria, Virginia on April 3, 1928 to Theodore Lloyd, Sr. and Daisy Lloyd. His father worked in the coal industry and his mother was a stay-at-home mom. Being a high school standout, Lloyd was named to the All-South Atlantic Conference three times and the All-State Virginia Interscholastic Conference twice. Lloyd did attend a segregated school, but gives gratitude to his family and educators for helping him through the tough times and his success after school.Lloyd was a 1946 graduate of Parker–Grey High School, where he played for Coach Louis Randolph Johnson. He received a scholarship to play basketball at West Virginia State University, home of the Yellow Jackets. In school he was nicknamed “Moon Fixer” because of his size and was known as a defensive specialist.Lloyd led West Virginia State to two Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association (CIAA) Conference and Tournament Championships in 1948 and 1949. He was named All–Conference three times (1948–50) and was All-American twice, as named by the Pittsburgh Courier (1949–50). As a senior, he averaged 14 points and 8 rebounds per game, while leading West Virginia State to a second–place finish in the CIAA Conference and Tournament Championship. In 1947–48, West Virginia State was the only undefeated team in the United States, with a 30–0 record. Lloyd graduated from WVSU with his B.S. degree in physical education in 1950.Lloyd was drafted in the 9th round with pick #100 by the Washington Capitols in the 1950 NBA draft. Nicknamed “The Big Cat”, Lloyd was one of three black players to enter the NBA at the same time. It was because of the order in which the team’s season openers fell that Lloyd was the first to actually play in a game in the NBA, scoring six points on Halloween night. The date was October 31, 1950, one day ahead of Chuck Cooper of the Boston Celtics and four days before Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton of the New York Knicks.Lloyd played in over 560 games in nine seasons. The 6-foot-5, 225-pound forward played in only seven games for the Washington Capitols before the team folded on January 9, 1951. He was then drafted into the U.S. Army at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. While fulfilling his military duty, the Syracuse Nationals picked him up on waivers. Lloyd served time fighting in the Korean War before coming back to basketball in 1952. In the 1953–54 season, Lloyd led the NBA in both personal fouls and disqualifications.In 1954-1955, Lloyd averaged career highs of 10.2 points and 7.7 rebounds for Syracuse, which beat the Fort Wayne Pistons 4 games to 3 to win the 1955 NBA Championship. Lloyd and Jim Tucker became the first African–Americans to play on an NBA championship team. Lloyd spent six seasons with Syracuse and two with the Detroit Pistons before retiring in 1961.Regarding the racism black players faced in the early years of the NBA, Lloyd recalled being refused service multiple times and an incident where a fan in Indiana spit on him. However, Lloyd persevered and said that these instances only pushed him and made him play harder. Saying he didn’t encounter racial animosity from teammates or opposing players, Lloyd said of fans’ antics, “My philosophy was: If they weren’t calling you names, you weren’t doing nothing. If they’re calling you names, you were hurting them.””In 1950, basketball was like a babe in the woods; it didn’t enjoy the notoriety that baseball enjoyed,” Lloyd once said. “I don’t think my situation was anything like Jackie Robinson’s-a guy who played in a hostile environment, where some of his teammates didn’t want him around. In basketball, folks were used to seeing integrated college teams. There was a different mentality.”“He’s an unsung star. Anybody can score. Lloyd was an excellent defensive player. That was No. 1 on my roster,” said his Syracuse Coach Al Cervi.In his NBA career with the Washington Capitols (1950–1951), Syracuse Nationals (1952–1958) and Detroit Pistons (1958–1960), Earl averaged 8.4 points, 6.4 rebounds and 1.4 assists in 560 games over nine seasons.According to Detroit News sportswriter Jerry Green, in 1965 Detroit Pistons General Manager Don Wattrick wanted to hire Lloyd as the team’s head coach.[citation needed] Dave DeBusschere was instead named Pistons player–coach. Lloyd was the first African–American assistant coach and was named head coach for the 1971–72 season, making him the third African–American head coach, after John McLendon and Bill Russell.A 2–5 start to the following campaign resulted in Lloyd being relieved of his duties and replaced by assistant coach Ray Scott on October 28, 1972. He had an overall record of 22–55 with the Pistons.Lloyd worked for the Pistons as a scout for five seasons. Lloyd is credited with helping draft Bailey Howell and discovering Willis Reed, Earl Monroe, Ray Scott and Wally Jones.After his basketball career, Lloyd worked during the 1970s and 1980s as a job placement administrator for the Detroit public school system. During this time, Lloyd also ran programs for underprivileged children teaching job skills.Lloyd served as Community Relations Director for the Bing Group, a Detroit manufacturing company in the 1990s.Approached by a young African–American player who said he was indebted to Lloyd for opening the doors for future generations of black players, Lloyd replied that he owed him absolutely nothing.“You cannot understand what an honor this is,” Lloyd said in 2007 about the court at T. C. Williams High School being named in his honor. “There’s no better honor than being validated by people who know you best. I will always, always treasure this.”Lloyd and his wife, Charlita, have three sons and four grandchildren. Lloyd resided in Fairfield Glade, Tennessee, just outside Crossville, Tennessee, until his death on February 26, 2015.In 1993, Lloyd was inducted into the Virginia Sports Hall of Fame.Lloyd was inducted into the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association (CIAA) Hall of Fame in 1998.The state of Virginia, proclaimed on February 9, 2001 as “Earl Lloyd Day” by action of Virginia’s Governor.In 2003, Lloyd was inducted to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame as a contributor.Lloyd was named to the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics Silver and Golden Anniversary Teams.The newly constructed basketball court at T. C. Williams High School in Lloyd’s home town of Alexandria, Virginia, was named in his honor in 2007. Lloyd attended Parker-Gray High School, as Alexandria’s schools were racially-segregated at the time. T.C. Williams—the subject of the motion picture Remember the Titans—was created as a combined, desegregated school two decades later.In November 2009, Moonfixer: The Basketball Journey of Earl Lloyd, was released. Lloyd wrote this biography with Syracuse area writer, Sean Kirst.In 2012, Lloyd was inducted into the Michigan Sports Hall of Fame.In 2014, a statue of Earl Lloyd was unveiled at West Virginia State University in the Walker Convocation Center. That same year, the “Earl Lloyd Classic” began, hosted at West Virginia State.In 2015 Lloyd, along with fellow basketball player Alonzo Mourning, was one of eight Virginians honored in the Library of Virginia’s “Strong Men & Women in Virginia History” because of his contributions to the sport of basketball.In 2018, the road running in front of the Walker Convocation Center at West Virginia State University was renamed “Earl Lloyd Way.” Research more about vthis great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

Month: October 2021

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American middle-distance runner, winner of the 800 m event at the 1936 Summer Olympics.

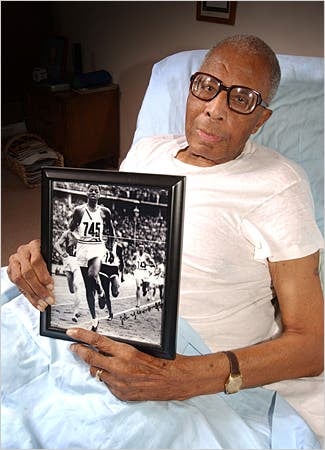

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American middle-distance runner, winner of the 800 m event at the 1936 Summer Olympics. I learned about him in Junior High School in Trenton, NJ and decided to run the 800 in his honor and the Long Jump for what Jesse Owens did. I met him in Trenton, N.J. in 1968, when he was living in Highstown, N.J.Woodruff was only a freshman at the University of Pittsburgh in 1936 when he placed second at the National AAU meet and first at the Olympic Trials (in the heat 1:49.9; WR 1:49.![]() , earning a spot on the U.S. Olympic team. Woodruff was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.Despite his inexperience, he was the favorite in the Olympic 800 meter run, and he did not disappoint. In one of the most exciting races in Olympic history, Woodruff became boxed in by other runners and was forced to stop running. He then came from behind to win in 1:52.9. The New York Times described the race:He remembers the anguish of his Olympic race: “Phil Edwards, the Canadian doctor, set the pace, and it was very slow. On the first lap, I was on the inside, and I was trapped. I knew that the rules of running said if I tried to break out of a trap and fouled someone, I would be disqualified. At that point, I didn’t think I could win, but I had to do something.”Woodruff was a 21-year-old college freshman, an unsophisticated and, at 6 feet 3 inches (1.91 m), an ungainly runner. But he was a fast thinker, and he made a quick decision.”I didn’t panic,” he said. “I just figured if I had only one opportunity to win, this was it. I’ve heard people say that I slowed down or almost stopped. I didn’t almost stop. I stopped, and everyone else ran around me.”Then, with his stride of almost 10 feet (3.0 m), Woodruff ran around everyone else. He took the lead, lost it on the backstretch, but regained it on the final turn and won the gold medal.During a career that was curtailed by World War II, Woodruff won one AAU (Amateur Athletic Union) title in 800 m in 1937 and won both 440 yd (400 m) and 880 yd (800 m) IC4A titles from 1937 to 1939. Woodruff also held a share of the world 4×880 yd relay record while competing with the national team.Woodruff graduated from the University of Pittsburgh in 1939, with a major in sociology. While at the University of Pittsburgh Woodruff became a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity. and then earned a master’s degree in the same field from New York University in 1941.He entered military service in 1941 as a second lieutenant and was discharged as a captain in 1945. He re-entered military service during the Korean War, and left in 1957 as a lieutenant colonel. He was the battalion commander of the 369th Artillery, later the 569 Transportation Battalion New York Army National Guard.In later years Woodruff lived in New Rochelle in Westchester County, New York and in Hightstown, New Jersey. He coached young athletes and officiated at local and Madison Garden track meets. Woodruff also worked as a teacher in New York City, a special investigator for the New York Department of Welfare, a recreation center director for the New York City Police Athletic League, a parole officer for the state of New York, a salesperson for Schieffelin and Co. and an assistant to the Center Director for Edison Job Corps Center in New Jersey.In the late 1990s John, with his wife Rose, retired to Fountain Hills, Arizona residing at Fountain View Village retirement community. Woodruff’s last public appearance was on April 15, 2007 when he, along with the members of the Tuskegee Airmen, was honored by the Arizona Diamondbacks by throwing out the first pitch. John Woodruff is buried at Crown Hill Cemetery, Indianapolis (section 46, lot 86).Each year, a 5-kilometer road race is held in Connellsville to honor Woodruff.Today in our History – October 30, 2007 – John Youie “Long John” Woodruff died.John Woodruff was the last surviving U.S. gold-medalist from the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. The 21-year-old freshman from the University of Pittsburgh won the middle distance 800-meter race on August 1, 1936 and he did it with a daring maneuver that carried him from dead last to victory.Along with the four gold medals won that year by Jesse Owens, John Woodruff’s victory helped challenge notions of Aryan racial supremacy before a stadium of spectators that included Adolph Hitler and other leaders of Germany’s Nazi regime.John Woodruff went on to win championships and set time records in numerous races while earning degrees in sociology from the University of Pittsburgh and New York University. After serving as an officer in the army during World War II, the sociologist worked for public agencies including several that helped disadvantaged youth. John Woodruff is the grandson of Virginia slaves and the son of a steelworker. He has two children and lives in Arizona with his second wife RoseJohn Woodruff was born on July 5, 1915 in Connellsville, Pennsylvania, a small town in the heart of steelmaking country. Though the town was prosperous John’s parents were poor. His father Silas, the son of Virginia slaves, worked for the H.C. Frick Coke Company. His mother, Sarah, was a spiritual woman who gave birth to 12 children, six of whom died in infancy. John was especially close to his mother and to an older sister Margaret, who resembled her.Hard work was valued more than school in the Woodruff household. So neither his father, who had an eighth grade education, nor his mother, who had a second grade education, took much notice when their next to youngest child, John, became an avid reader. John recalls startling his own second grade teacher by finishing books several years beyond his level. He also remembers signing his own report cards because his father was functionally illiterate.By the time John reached high school the Great Depression had brought hard times to Connellsville. When some of John’s white classmates dropped out to take factory jobs John tried to do the same. But the 16-year-old was told the company was not hiring Negroes so he went back to school. He says that the experience marked the one time discrimination worked to his benefit.In the 11th grade John made the football team. Each practice wound up with a run up to the cemetery and back to the field. At just over six-feet-three-inches tall, John had a nine-foot running stride that would later earn him the nickname ‘Long John Woodruff’. That stride instantly grabbed the attention of assistant football coach and track coach Joseph Larew.Unfortunately the only thing John’s mother noticed was that her son was getting home from school too late for his chores. She demanded that he quit. But the track team required less time than football so in the spring coach Larew convinced John to sign up. In his first competition John won both the 880-yard and one-mile runs.At a meet in Morgantown, West Virginia he met Ohio State’s star runner Jesse Owens who became a friend and inspiration – putting John on track to becoming a star athlete and the first – and only – member of his family to finish high school. (John notes that his sister Margaret eventually earned her GED and became a nurse.)Unfortunately his mother would not live to see her son graduate. In 1935 she died of cancer at the age of 59. Despite the personal tragedy, John Woodruff set school, county, district, and state records and broke the national school mile record with a time of 4:23.4. He also scored an athletic scholarship to the University of Pittsburgh.John credits Pitt track coach Carl Olson with helping him get to college but once there campus life posed severe financial hardships for the 20-year-old. He recalls arriving with just 25 cents in his pocket and living at a YMCA infested with bedbugs. To earn money and qualify for meal benefits he took assorted jobs including cleaning the athletic facilities and working on the campus grounds.He planned to study physical education but switched to Sociology and History due to his interest in people his love of books. Meanwhile, on the field his freshman year, he swept up gold medals at the Penn Relays and National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) meets, prompting Coach Olson to invite John to try out for the 1936 Summer Olympic Games in Berlin, Germany. He landed a spot on the U.S. men’s track and field team which included several other African-Americans including Jesse Owens.At the time America’s participation in the games was in question. John recalls, “There was some talk about the Olympics being boycotted because of what Hitler was doing to the Jewish people in Germany. But it was never discussed amongst team members.We heard something about it, but we never discussed it. We weren’t interested in the politics you see at all we were only interested in going to Germany and winning.” In July he celebrated his twenty-first birthday and then sailed to Germany. Despite being nervous about his first voyage overseas, teammates were drawn to John. He won their respect and forged friendships that would last a lifetime.At the games John won the semi-finals of the 800-meter race by 20 yards. But in the final event he made a tactical mistake – a mistake he turned into an unforgettable moment of triumph. He has recounted the story many times: “Phil Edwards (a five-time Olympic medalist from Canada) jumped right in front and set a very, very slow pace.I decided due to my lack of experience I would follow him. … The pace was so slow, and all the runners crowded right around me…I had enough experience to know if I tried to get out of the trap, I was going to be disqualified. So I moved out into the third lane, and I let all the runners precede me. That’s what made the race very outstanding.I actually started the race twice.” Restarting from a dead stop behind the other contenders John passed them all. His winning time of 1:52:9 led some to wonder how much faster it might have been had he not been caught in the pack. The New York Herald-Tribune called it the “most daring move seen on a track.”John has said, “I didn’t know I was going to win that race. I really didn’t. I just took advantage of the opportunity to get there to give me a chance to win it.” Woodruff became the first American to win the Gold in the 800-meter race in more than 20 years. He still remembers the elation he felt on the victory stand. Contrary to some reports that Hitler and the Germans overtly snubbed the black athletes, John says he was treated extremely well especially by the public.Following a tour of Europe with teammates to compete in local meets, Connellsville threw John a homecoming parade. The town presented him with a gold watch (later stolen) and John gave the town a small German oak tree that had been presented to each medal winner. Not many of the trees had survived the trip home and time spent in the hands of agricultural inspectors. But John had taken pains to reclaim his sapling and to see it that was nursed back to health.Once he returned to college for his sophomore year his gratitude and elation met with the sobering realities of racism in America. First he was excluded from competing at a track meet at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis. “Navy refused to allow Pitt to come if they brought me. I could not go because I was black.”And, when he did travel with the team, the star athlete was routinely required to stay apart from the whites. But the biggest blow came in 1937 when Woodruff says biased officials deprived him of a world record at the Greater Texas and Pan American Exposition games. The trip south started badly with Pitt’s black athletes having to threaten to withdraw from competition to gain access to the train’s dining car.And once in Dallas, they were bused to a YMCA to sleep on cots in a gym. Then John ran the fastest race of his life in the 880-yard track event, beating world record holder Elroy Robinson with a time of 1:47.8. But officials who had certified the measurement of the track before the race, re-measured it and found to be six feet short. John was devastated and has said, “You know what happened. Those boys got their heads together and decided they weren’t going to give a black man a white man’s record.”Though bitter, he continued to compete, maintaining his amateur status while earning his undergraduate degree. In relay after relay he racked up wins and set records. He became the first athlete to ever anchor three championship relays in a year in 1938, and did it again in 1939.He is especially proud of anchoring the Sprint Medley Relays held in Philadelphia that set a new world record in 1939, a stat that is recorded on the back wall of the stadium at Franklin Field. Author Jim Kriek once summed up his varsity accomplishments by saying they, “included three national collegiate half-mile championships, three IC4A championships in the 440 and 880, a new American record in the 800-meters, a world record half-mile run at the Cotton Bowl, in Dallas, Texas, national AAU half-mile championships, and various school and state honors.”On June 7, 1940 he set an American record in the 800-meter race1:48:60. That same year he graduated from the University of Pittsburgh, and went on New York University, earning a master’s degree in Sociology in 1941.If not for World War II he may have become a university professor and participated in another Olympic competition. Instead he entered the army as a Second Lieutenant and the following year he married. Among the guests at John’s 1942 wedding to Hattie Davis was good friend Jesse Owens. The Woodruff’s had two children, Randelyn (Randy) Gilliam, now a retired teacher living in Chicago and John, Jr. now a trial attorney in New York.During the war John rose to the rank of Lt. Colonel and was discharged from active duty in 1945. He returned to New York and held jobs with government agencies as a parole officer, teacher and special investigator for the New York Department of Welfare. He also worked for the New York City Children’s Aid Society and was once the Recreation Center Director for the New York City Police Athletic League.In 1968, John accepted a job in Indiana to manage residents enrolled in the U.S. Job Corps, a federal anti-poverty program aimed at helping at-risk youth. Ultimately the move split the Woodruff family and led to divorce. In 1970, John married his current wife Rose, and they relocated with the Job Corps to Hightstown, New Jersey. John retired from the Jobs Corps later that year.In 1972 John returned to Germany to watch the Munich Olympic Games as a special guest of the government. And for many years he made the annual trip to Philadelphia officiate at the Penn Relays. For generations of runners he has served as a role model – and for many, as a friend. Until their deaths John maintained relationships with fellow athletes Jesse Owens and Ralph Metcalfe, a runner once known as the world’s fastest human being. And he still keeps in touch with 1936 Olympian Margaret Bergmann Lambert, a German high jumper excluded from competition because she was Jewish.Another close friend is Herb Douglas, a 1948 Olympic long jump bronze medalist who calls John Woodruff his mentor. John also inspired many unknown to him personally. For years he was a popular speaker at the Peddie School near his New Jersey home advising students to, “get an education, have courage and never give up.”In the 1970’s John Woodruff donated memorabilia from his track career to his high school and today his Olympic gold medal hangs in the library at the University of Pittsburgh. There are numerous other honors too.The annual John Woodruff Day in Connellsville, Pennsylvania includes a 5k run and walk and scholarships that give new generations opportunities to advance their education. And in 1994, he received the most votes of any athlete selected for the inaugural class of the Penn Relays Wall of Fame.John remains proud of his achievements and says he has no regrets even though he has paid a heavy price for the years of high impact running. After enduring spine surgery, heart problems and a hip replacement, poor circulation caused doctors to amputate both of his legs above the knees in 2001.But his spirit has not dimmed. He remains in touch with friends and an extended family that now includes five grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. And he continues to read. His favorite books are the Bible, and novels about great historical figures including Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Albert Einstein.Perhaps the perfect metaphor for his life is the fate of the tree that he carried back from Berlin in 1936. It now stands 78-feet tall. It’s become known as the ‘Woodruff Oak’ and by some accounts it’s the only one of those commemorative gifts still alive and producing fertile acorns.Like the man himself it is a towering presence at Connellsville High and a symbol of strength and resilience that represents John Woodruff’s legacy. Recearch more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

, earning a spot on the U.S. Olympic team. Woodruff was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.Despite his inexperience, he was the favorite in the Olympic 800 meter run, and he did not disappoint. In one of the most exciting races in Olympic history, Woodruff became boxed in by other runners and was forced to stop running. He then came from behind to win in 1:52.9. The New York Times described the race:He remembers the anguish of his Olympic race: “Phil Edwards, the Canadian doctor, set the pace, and it was very slow. On the first lap, I was on the inside, and I was trapped. I knew that the rules of running said if I tried to break out of a trap and fouled someone, I would be disqualified. At that point, I didn’t think I could win, but I had to do something.”Woodruff was a 21-year-old college freshman, an unsophisticated and, at 6 feet 3 inches (1.91 m), an ungainly runner. But he was a fast thinker, and he made a quick decision.”I didn’t panic,” he said. “I just figured if I had only one opportunity to win, this was it. I’ve heard people say that I slowed down or almost stopped. I didn’t almost stop. I stopped, and everyone else ran around me.”Then, with his stride of almost 10 feet (3.0 m), Woodruff ran around everyone else. He took the lead, lost it on the backstretch, but regained it on the final turn and won the gold medal.During a career that was curtailed by World War II, Woodruff won one AAU (Amateur Athletic Union) title in 800 m in 1937 and won both 440 yd (400 m) and 880 yd (800 m) IC4A titles from 1937 to 1939. Woodruff also held a share of the world 4×880 yd relay record while competing with the national team.Woodruff graduated from the University of Pittsburgh in 1939, with a major in sociology. While at the University of Pittsburgh Woodruff became a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity. and then earned a master’s degree in the same field from New York University in 1941.He entered military service in 1941 as a second lieutenant and was discharged as a captain in 1945. He re-entered military service during the Korean War, and left in 1957 as a lieutenant colonel. He was the battalion commander of the 369th Artillery, later the 569 Transportation Battalion New York Army National Guard.In later years Woodruff lived in New Rochelle in Westchester County, New York and in Hightstown, New Jersey. He coached young athletes and officiated at local and Madison Garden track meets. Woodruff also worked as a teacher in New York City, a special investigator for the New York Department of Welfare, a recreation center director for the New York City Police Athletic League, a parole officer for the state of New York, a salesperson for Schieffelin and Co. and an assistant to the Center Director for Edison Job Corps Center in New Jersey.In the late 1990s John, with his wife Rose, retired to Fountain Hills, Arizona residing at Fountain View Village retirement community. Woodruff’s last public appearance was on April 15, 2007 when he, along with the members of the Tuskegee Airmen, was honored by the Arizona Diamondbacks by throwing out the first pitch. John Woodruff is buried at Crown Hill Cemetery, Indianapolis (section 46, lot 86).Each year, a 5-kilometer road race is held in Connellsville to honor Woodruff.Today in our History – October 30, 2007 – John Youie “Long John” Woodruff died.John Woodruff was the last surviving U.S. gold-medalist from the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. The 21-year-old freshman from the University of Pittsburgh won the middle distance 800-meter race on August 1, 1936 and he did it with a daring maneuver that carried him from dead last to victory.Along with the four gold medals won that year by Jesse Owens, John Woodruff’s victory helped challenge notions of Aryan racial supremacy before a stadium of spectators that included Adolph Hitler and other leaders of Germany’s Nazi regime.John Woodruff went on to win championships and set time records in numerous races while earning degrees in sociology from the University of Pittsburgh and New York University. After serving as an officer in the army during World War II, the sociologist worked for public agencies including several that helped disadvantaged youth. John Woodruff is the grandson of Virginia slaves and the son of a steelworker. He has two children and lives in Arizona with his second wife RoseJohn Woodruff was born on July 5, 1915 in Connellsville, Pennsylvania, a small town in the heart of steelmaking country. Though the town was prosperous John’s parents were poor. His father Silas, the son of Virginia slaves, worked for the H.C. Frick Coke Company. His mother, Sarah, was a spiritual woman who gave birth to 12 children, six of whom died in infancy. John was especially close to his mother and to an older sister Margaret, who resembled her.Hard work was valued more than school in the Woodruff household. So neither his father, who had an eighth grade education, nor his mother, who had a second grade education, took much notice when their next to youngest child, John, became an avid reader. John recalls startling his own second grade teacher by finishing books several years beyond his level. He also remembers signing his own report cards because his father was functionally illiterate.By the time John reached high school the Great Depression had brought hard times to Connellsville. When some of John’s white classmates dropped out to take factory jobs John tried to do the same. But the 16-year-old was told the company was not hiring Negroes so he went back to school. He says that the experience marked the one time discrimination worked to his benefit.In the 11th grade John made the football team. Each practice wound up with a run up to the cemetery and back to the field. At just over six-feet-three-inches tall, John had a nine-foot running stride that would later earn him the nickname ‘Long John Woodruff’. That stride instantly grabbed the attention of assistant football coach and track coach Joseph Larew.Unfortunately the only thing John’s mother noticed was that her son was getting home from school too late for his chores. She demanded that he quit. But the track team required less time than football so in the spring coach Larew convinced John to sign up. In his first competition John won both the 880-yard and one-mile runs.At a meet in Morgantown, West Virginia he met Ohio State’s star runner Jesse Owens who became a friend and inspiration – putting John on track to becoming a star athlete and the first – and only – member of his family to finish high school. (John notes that his sister Margaret eventually earned her GED and became a nurse.)Unfortunately his mother would not live to see her son graduate. In 1935 she died of cancer at the age of 59. Despite the personal tragedy, John Woodruff set school, county, district, and state records and broke the national school mile record with a time of 4:23.4. He also scored an athletic scholarship to the University of Pittsburgh.John credits Pitt track coach Carl Olson with helping him get to college but once there campus life posed severe financial hardships for the 20-year-old. He recalls arriving with just 25 cents in his pocket and living at a YMCA infested with bedbugs. To earn money and qualify for meal benefits he took assorted jobs including cleaning the athletic facilities and working on the campus grounds.He planned to study physical education but switched to Sociology and History due to his interest in people his love of books. Meanwhile, on the field his freshman year, he swept up gold medals at the Penn Relays and National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) meets, prompting Coach Olson to invite John to try out for the 1936 Summer Olympic Games in Berlin, Germany. He landed a spot on the U.S. men’s track and field team which included several other African-Americans including Jesse Owens.At the time America’s participation in the games was in question. John recalls, “There was some talk about the Olympics being boycotted because of what Hitler was doing to the Jewish people in Germany. But it was never discussed amongst team members.We heard something about it, but we never discussed it. We weren’t interested in the politics you see at all we were only interested in going to Germany and winning.” In July he celebrated his twenty-first birthday and then sailed to Germany. Despite being nervous about his first voyage overseas, teammates were drawn to John. He won their respect and forged friendships that would last a lifetime.At the games John won the semi-finals of the 800-meter race by 20 yards. But in the final event he made a tactical mistake – a mistake he turned into an unforgettable moment of triumph. He has recounted the story many times: “Phil Edwards (a five-time Olympic medalist from Canada) jumped right in front and set a very, very slow pace.I decided due to my lack of experience I would follow him. … The pace was so slow, and all the runners crowded right around me…I had enough experience to know if I tried to get out of the trap, I was going to be disqualified. So I moved out into the third lane, and I let all the runners precede me. That’s what made the race very outstanding.I actually started the race twice.” Restarting from a dead stop behind the other contenders John passed them all. His winning time of 1:52:9 led some to wonder how much faster it might have been had he not been caught in the pack. The New York Herald-Tribune called it the “most daring move seen on a track.”John has said, “I didn’t know I was going to win that race. I really didn’t. I just took advantage of the opportunity to get there to give me a chance to win it.” Woodruff became the first American to win the Gold in the 800-meter race in more than 20 years. He still remembers the elation he felt on the victory stand. Contrary to some reports that Hitler and the Germans overtly snubbed the black athletes, John says he was treated extremely well especially by the public.Following a tour of Europe with teammates to compete in local meets, Connellsville threw John a homecoming parade. The town presented him with a gold watch (later stolen) and John gave the town a small German oak tree that had been presented to each medal winner. Not many of the trees had survived the trip home and time spent in the hands of agricultural inspectors. But John had taken pains to reclaim his sapling and to see it that was nursed back to health.Once he returned to college for his sophomore year his gratitude and elation met with the sobering realities of racism in America. First he was excluded from competing at a track meet at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis. “Navy refused to allow Pitt to come if they brought me. I could not go because I was black.”And, when he did travel with the team, the star athlete was routinely required to stay apart from the whites. But the biggest blow came in 1937 when Woodruff says biased officials deprived him of a world record at the Greater Texas and Pan American Exposition games. The trip south started badly with Pitt’s black athletes having to threaten to withdraw from competition to gain access to the train’s dining car.And once in Dallas, they were bused to a YMCA to sleep on cots in a gym. Then John ran the fastest race of his life in the 880-yard track event, beating world record holder Elroy Robinson with a time of 1:47.8. But officials who had certified the measurement of the track before the race, re-measured it and found to be six feet short. John was devastated and has said, “You know what happened. Those boys got their heads together and decided they weren’t going to give a black man a white man’s record.”Though bitter, he continued to compete, maintaining his amateur status while earning his undergraduate degree. In relay after relay he racked up wins and set records. He became the first athlete to ever anchor three championship relays in a year in 1938, and did it again in 1939.He is especially proud of anchoring the Sprint Medley Relays held in Philadelphia that set a new world record in 1939, a stat that is recorded on the back wall of the stadium at Franklin Field. Author Jim Kriek once summed up his varsity accomplishments by saying they, “included three national collegiate half-mile championships, three IC4A championships in the 440 and 880, a new American record in the 800-meters, a world record half-mile run at the Cotton Bowl, in Dallas, Texas, national AAU half-mile championships, and various school and state honors.”On June 7, 1940 he set an American record in the 800-meter race1:48:60. That same year he graduated from the University of Pittsburgh, and went on New York University, earning a master’s degree in Sociology in 1941.If not for World War II he may have become a university professor and participated in another Olympic competition. Instead he entered the army as a Second Lieutenant and the following year he married. Among the guests at John’s 1942 wedding to Hattie Davis was good friend Jesse Owens. The Woodruff’s had two children, Randelyn (Randy) Gilliam, now a retired teacher living in Chicago and John, Jr. now a trial attorney in New York.During the war John rose to the rank of Lt. Colonel and was discharged from active duty in 1945. He returned to New York and held jobs with government agencies as a parole officer, teacher and special investigator for the New York Department of Welfare. He also worked for the New York City Children’s Aid Society and was once the Recreation Center Director for the New York City Police Athletic League.In 1968, John accepted a job in Indiana to manage residents enrolled in the U.S. Job Corps, a federal anti-poverty program aimed at helping at-risk youth. Ultimately the move split the Woodruff family and led to divorce. In 1970, John married his current wife Rose, and they relocated with the Job Corps to Hightstown, New Jersey. John retired from the Jobs Corps later that year.In 1972 John returned to Germany to watch the Munich Olympic Games as a special guest of the government. And for many years he made the annual trip to Philadelphia officiate at the Penn Relays. For generations of runners he has served as a role model – and for many, as a friend. Until their deaths John maintained relationships with fellow athletes Jesse Owens and Ralph Metcalfe, a runner once known as the world’s fastest human being. And he still keeps in touch with 1936 Olympian Margaret Bergmann Lambert, a German high jumper excluded from competition because she was Jewish.Another close friend is Herb Douglas, a 1948 Olympic long jump bronze medalist who calls John Woodruff his mentor. John also inspired many unknown to him personally. For years he was a popular speaker at the Peddie School near his New Jersey home advising students to, “get an education, have courage and never give up.”In the 1970’s John Woodruff donated memorabilia from his track career to his high school and today his Olympic gold medal hangs in the library at the University of Pittsburgh. There are numerous other honors too.The annual John Woodruff Day in Connellsville, Pennsylvania includes a 5k run and walk and scholarships that give new generations opportunities to advance their education. And in 1994, he received the most votes of any athlete selected for the inaugural class of the Penn Relays Wall of Fame.John remains proud of his achievements and says he has no regrets even though he has paid a heavy price for the years of high impact running. After enduring spine surgery, heart problems and a hip replacement, poor circulation caused doctors to amputate both of his legs above the knees in 2001.But his spirit has not dimmed. He remains in touch with friends and an extended family that now includes five grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. And he continues to read. His favorite books are the Bible, and novels about great historical figures including Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Albert Einstein.Perhaps the perfect metaphor for his life is the fate of the tree that he carried back from Berlin in 1936. It now stands 78-feet tall. It’s become known as the ‘Woodruff Oak’ and by some accounts it’s the only one of those commemorative gifts still alive and producing fertile acorns.Like the man himself it is a towering presence at Connellsville High and a symbol of strength and resilience that represents John Woodruff’s legacy. Recearch more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

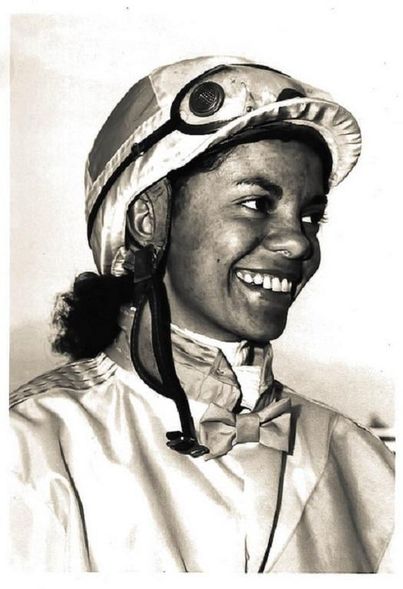

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was the first African American female horse racing jockey and the first woman to serve as a California horse racing steward.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was the first African American female horse racing jockey and the first woman to serve as a California horse racing steward.Licensed to ride at Thistledown in North Randall, Ohio, when she was 17 years old, White began her career riding for her father, trainer Raymond White, in June 1971.She finished 11th in her first race, on a gelding named Ace Reward. White earned her first win as a jockey on September 3, 1971, riding Jetolara to victory at Waterford Park (now Mountaineer Park) in Chester, West Virginia.Today in our History – October 29, 1953 – Cheryl White (October 29, 1953 — September 20, 2019) was born. White’s debut on track garnered significant attention. National newspapers covered her first start as a jockey, and she appeared on the cover of the July 29, 1971 issue of Jet Magazine.White is credited with 226 wins and earnings of $762,624 in Thoroughbred racing, but her career also included Quarter Horse, Arabian, Paint, and Appaloosa racing. In total, White estimates that she won about 750 races. As a Thoroughbred rider, White became the first woman to win two races on the same day in two states in 1971 when she rode a winner at Thistledown and then at Waterford. She was also the first female jockey to win five races in one day, accomplishing that feat on October 19, 1983 at Fresno Fair.As an Appaloosa rider, White was the first woman to win the Appaloosa Horse Club’s Jockey of the Year award, scoring the title in 1977, and then again in 1983, 1984, and 1985. She was inducted into the Appaloosa Hall of Fame in 2011.After passing the California Horse Racing Board’s Steward Examination in 1991, White retired from riding in 1992 to become a racing official. She returned to the saddle for appearances in the Lady Legends for the Cure event held by Pimlico Race Course from 2010-2014. Her final ride was aboard Macho Spaces at Pimlico in 2014.Born in Cleveland, White died on September 20, 2019 at the age of 65, in Youngstown, Ohio.[11] “Cheryl was never a great self-promoter, and wasn’t concerned with the politics of racing,” her brother, Raymond White Jr., said in a press release announcing her death. “She just did her thing. She didn’t understand what she had accomplished. I don’t know that she understood her significance, or place in history.” Cheryl White, America’s first black female jockey, passed away at the age of 65 on September 20, 2019. Her memorial was held on October 18 at Thistledown Race Track in Cleveland, OH, where she rode her first race on June 15, 1971 at the age of 17.Cheryl was no stranger to horses growing up. She was born into a horse racing family and was raised on a horse farm. Her father, Raymond White, Sr., was an accomplished Thoroughbred trainer, and her mother, Doris, was a racehorse owner.Over the course of her 21-year career as a jockey, Cheryl won over 750 races. As reported by a recent betchicago article, when asked about her first race at Thistledown, astride a horse named Ace Reward, Cheryl said, “I just wanted those gates to open. I wasn’t nervous and knew I’d be first out and get the lead.”Cheryl was right. Ace Reward started off in the lead in the fifth race at Cleveland’s Thistledown Race Track and for about three-eighths of a mile in the $2,600, six-furlong race, it looked as if the filly would carry her rider to a historic victory. However, the filly lagged and the pair finished last out of 11 horses.Be that as it may, the five-foot-three, 107-pound White, atop her father’s horse, made history as the first black female jockey in the United States. That outing was the first of two scheduled probationary rides for White as she worked toward becoming the first nonwhite woman licensed to jockey.That wouldn’t be the only time Cheryl White would make history.On September 2, 1971, at Waterford Park, Cheryl became the first black woman to win a Thoroughbred horse race in the United States. As a Thoroughbred jockey, she also because the first woman to win two races on the same day in two states when she won a race in Thistledown in Ohio and then another one at Waterford Park in West Virginia. Cheryl accomplished another historic milestone when, on October 19, 1983 at the Fresno Fair, she because the first female jockey to win five races in one day.Cheryl graced the cover of the July 1971 issue of Jet magazine and the front page of The Plain Dealer on June 16, 1971 due to her groundbreaking achievements and for breaking the color barrier in horse racing. She is also in the Appaloosa Hall of Fame, has been nominated for the Cleveland Sports Hall of Fame and is a recipient of the Award of Merit by the African American Sports Hall of Fame.Cheryl’s family would like to create a permanent memorial and foundation in her honor. The foundation will help inspire and introduce horses, horse racing, riding and other aspects of the industry to children who are underprivileged and at risk, but will be open to all children no matter their background.To donate to the Cheryl White Memorial Foundation, visit this website. All donations will be put towards the permanent memorial and foundation.“Cheryl was never a great self-promoter, and wasn’t concerned with the politics of racing,” said her brother, Raymond White, Jr. “She just did her thing. She didn’t understand what she had accomplished. I don’t know that she understood her significance, or place in history.”Cheryl is survived by her brother Raymond White, Jr.; nephews Raymond White III, Christopher Scott and Luciano White; niece Nikki White; great-nieces Jocelyn White and Sheena White; great-nephew Raymond White IV; and countless racetrack friends that were her extended family.“Cheryl is a true legend and will be missed terribly by all who love her,” said Raymond. “We are extremely saddened and heartbroken beyond comprehension to have lost Cheryl. She has been taken home by God to join our mother and father, Doris and Raymond White Sr.” Reserach more about this great American champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was the first woman to be licensed as an assistant funeral director in Kanawha County, West Virginia.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was the first woman to be licensed as an assistant funeral director in Kanawha County, West Virginia.Remember – “I am convinced of the efficiency of direct action. If our people had used it a generation or two ago, we wouldn’t be witnessing the things today that shock and sadden people of all races.” – Elizabeth Harden GilmoreToday in our History – October 28, 1938 – Elizabeth Harden Gilmore, a business leader and civil rights advocate and as a funeral director on November 12, 1940.She opened the Harden and Harden Funeral Home in 1947 (now a National Historic site).She pioneered efforts to integrate West Virginia’s schools, housing, and public accommodations and to pass civil rights legislation enforcing such integration. In the early 1950s, before the Brown v. Board of Education decision mandating school desegregation, Gilmore formed a women’s club which opened Charleston’s first integrated day care center.At about the same time, she succeeded in getting her black Girl Scouts of the USA troop admitted to Camp Anne Bailey near the mountain town of Lewisburg. The two Girl Scouts that she sponsored to integrate Camp Anne Bailey were Deloris Foster and Linda Stillwell.Her Girl Scout Troop, 230 was, also, the first black troop to graduate from Girl Scouting in West Virginia. After co-founding the local chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in 1958, she led CORE in a successful one-year-long sit-in campaign at a local department store called The Diamond.In the 1960s, Gilmore served on the Kanawha Valley Council of Human Relations, where she participated in forums on racial differences and where she helped black renters, displaced by a new interstate highway, find housing.Her successful push to amend the 1961 state civil rights law won her a seat on the powerful higher-education Board of Regents. Gilmore was the first African American to receive such an honor. She stayed on the Board from 1969 to the late 1970s, serving one term as vice-president and one term as president. Her tireless commitment to civil and human rights did not end there. She was also involved with the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and community education and welfare committees.Elizabeth Harden Gilmore was a Charleston funeral director and a pioneer in the civil right movement in West Virginia. Gilmore was a leader and one of the founders of the local chapter of Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) that led sit-ins throughout Charleston.She also worked to secure the admission of African American Girl Scouts into the previously all-white Camp Anne Bailey. Gilmore led the first sit-in against the Diamond Department Store’s lunch counter in Downtown Charleston. Thanks to her leadership, the store opened the lunch counter to African American patrons in 1960. In 1988, Gilmore’s home was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.Efforts continue to restore the home and operate it in a way that honors Gilmore’s legacy.The Harden-Gilmore house was constructed in 1900 by an Italian immigrant and contractor, Dominic Minotti. Minotti also built the piers on the bridges that connect Kanawha City and South Charleston with Charleston. After several years of retirement, Minotti passed away in 1925. In the mid-1930s, Minotti’s wife passed away and the house became a boarding house for a brief period, and was then put up for sale. Elizabeth Harden Gilmore, the first woman to be a licensed funeral director in Kanawha County, purchased the home in 1947.Elizabeth Harden Gilmore bought the home, with her husband, when she was in her late 30s. They remodeled it to serve as both their home and funeral parlor, Harden and Harden Funeral Home. The ownership of the black funeral home in Charleston, WV, gave Gilmore a sense of recognition as a leader in the black community. Gilmore took this leadership seriously, and became a key figure in the civil rights movement in West Virginia. Gilmore fought for her daughter’s right to be admitted into Camp Anne Bailey. Her daughter’s Girl Scout troop was the first African American group to be admitted into the camp.Gilmore also co-founded the local chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality, or CORE, in 1958. Serving as the co-chairman and the executive secretary of CORE, Gilmore led the efforts of a sit-in at the local Diamond Department Store. After a year and a half long fight, Gilmore and CORE successfully convinced The Diamond to open their lunch counters to African-Americans. Elizabeth Harden Gilmore was active in an impressive number of civic organizations. She founded a women’s club in the early 1950s that opened and operated the first integrated day care center in Charleston. She served on the community welfare council and on the Executive Board of the Citizens Committee for a West Virginia Human Rights Law, a grassroots organization formed to achieve the passage of an enforceable civil rights law.Due to the efforts of that organization, the state civil rights law were amended in 1961. She was a member of the Charleston Chamber of Commerce (serving on their education task force), an adviser to the Volunteer Service Bureau, and a charter member of the Kanawha Valley Council of Human Relations.During her time on the council, she served as the group’s first Vice President, participated in their Panel of American Women (a public forum focused on race and religion), and worked to get African Americans into homes and neighborhoods that had excluded them in the past through the Clearing House for Open Occupancy Selection Effort.She also participated in the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. In 1969, Gilmore became the first African American appointed to the West Virginia Board of Regents, and eventually served as the vice president and then president. Research more about this great American Champion and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!

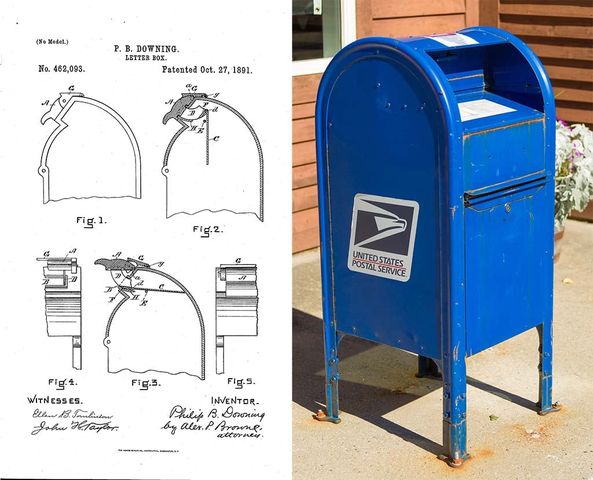

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion like many during the late nineteenth and the early twentieth century, he successfully filed at least five patents with the United States Patent Office.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion like many during the late nineteenth and the early twentieth century, he successfully filed at least five patents with the United States Patent Office. Among his most significant inventions were a street letter box (U.S. Patent numbers 462,092 and 462,093) and a mechanical device for operating street railway switches (U.S. Patent number 430,118). He also enjoyed a long career as a clerk with the Custom House in Boston, Massachusetts, retiring in 1927 after more than thirty years of service.Today in our History – October 27, 1891 – Black inventor Philip B. Downing receives patent for the street letter box, a precursor of the modern-day mailbox.Born in Providence, Rhode Island on March 22, 1857, Downing came from a prominent background. His father, George T. Downing, was a well-known abolitionist and business owner, while his mother, Serena L. deGrasse, had family roots in New York City, New York dating back to the mid-1600s. Philip Downing’s grandfather, Thomas Downing, had been born to emancipated parents in Virginia. He also had success in business, establishing Downing’s Oyster House in the financial district of Manhattan in 1825. It quickly became one of the city’s best-known dining and catering establishments. In addition, Thomas Downing played an important role in founding the United Anti-Slavery Society of the City of New York in the mid-1830s.One of six children, Philip Downing spent his childhood in Providence and Newport, Rhode Island, as well as in Washington, D.C., where his father was manager of the U.S. House of Representatives’ dining room. Census records indicate that Downing moved to Boston around 1880. Shortly thereafter, he married Evangeline Howard, and had two children, Antonia Downing and Philip Downing Jr.On June 17, 1890, the U.S. Patent Office approved Downing’s application for “new and useful Improvements in Street-Railway Switches.” His invention allowed the switches to be opened or closed by using a brass arm located next to the brake handle on the platform of the car. It also allowed the switches to be changed automatically in some cases.A little over a year later, on October 27, 1891, his two patents for a street letter box also gained approval. Downing’s design resembled the mailboxes that are now ubiquitous, a tall metal box with a secure, hinged door to drop letters. Until this point, those wishing to send mail usually had to travel to the post office. Downing’s invention would instead allow for drop off near one’s home and easy pick-up by a letter carrier. His idea for the hinged opening prevented rain or snow from entering the box and damaging the mail.More than twenty-five years later, on January 26, 1917, Downing would receive another patent (U.S. Patent number 1243,595), for an envelope moistener, which utilized a roller and a small, attached water tank, to quickly moisten envelopes. The following year saw another successful application (U.S. Patent number 126,9584) for an easily accessible desktop notepad.Philip Downing died in Boston on June 8, 1934. He was 77. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event happened On a chilly Louisiana afternoon in October 1868, Louis Wilson left the courthouse, where he’d testified in an ongoing case.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event happened On a chilly Louisiana afternoon in October 1868, Louis Wilson left the courthouse, where he’d testified in an ongoing case. Wilson was a freedman living in St. Bernard Parish, a rural community outside the city of New Orleans. The Civil War had been over for three years, and the 14th Amendment, which gave Wilson full citizenship, had passed just three months before. Across the South, tensions were high because of the upcoming presidential election that would decide the fate of Reconstruction.Today in our History – October 26, 1868 – UNRAVELING A FORGOTTEN MASSACRE IN MY LOUISIANA HOMETOWNToday in Our History – October 26, 1868 – White Terrorists Killed Several Blacks in St. Bernard Parish, near New Orleans.Wilson rode home alongside the winding Mississippi River, where he was confronted by a group of armed white men on horseback. He was aware that freed people had been killed the day before, but wrongly assumed that the carnage had ended. The men ordered him to dismount, and one of them struck his jaw with the butt of a shotgun. Wilson was thrown into a wagon with other captive freedmen and transported to a makeshift prison.Later that evening, Wilson and a few others were dragged out of their cells, lined up, and blasted with shotguns. Everyone was killed except Wilson, who somehow crawled into a nearby cane field and waited for three days until he felt safe. Over the next few days, white men tore through the parish, attempting to eliminate any further threats, leaving behind them a trail of black corpses. Estimates of the massacre range from 35 to more than 100 murdered.Historically, this event has usually been labeled “the St. Bernard riots.” It should be termed the 1868 St. Bernard Parish Massacre—one of the most brutal episodes of racist violence in U.S. history, as well as one of the most forgotten. I first came across it while working as a Louisiana history teacher in St. Bernard Parish, looking for events that my students would be able to relate to their own lives.What I discovered was that a murderous rampage had occurred in my hometown, and almost no one knew. The perpetrators never discussed their atrocities. Local records were lost due to numerous floods, including Hurricane Katrina in 2005.I researched these events for years, driving to and from work, down roads and past former cane fields that were once the bloody battleground of Reconstruction.Not only did I live in the very parish where the massacre took place, but the surnames of the assailants and the victims matched those of some of my students, both black and white, who worked together, played sports together, and shared lunches. As I delved deeper into U.S. Congressional archives, I uncovered investigations commissioned by the Freedmen’s Bureau and the Louisiana State Legislature, and correspondence with then-President Andrew Johnson.But my most startling discovery was that several of my students were the descendants of those involved, victims and perpetrators alike.The racial tension that sparked the massacre was not unique to St. Bernard Parish. By 1868, the South had lost the Civil War and was struggling to rebuild its battered economy, which had depended heavily on an enslaved population. Louisiana was under federal military occupation during Reconstruction, and black males had obtained the right to vote.The stakes were high for Southern elites in the presidential election, the first since the end of the war. If they could solidify a win for Horatio Seymour, a “Copperhead” Democrat who had promised to roll back Reconstruction policies, they might regain some of the power they had lost. Seymour railed against “Negro supremacy” and proudly painted himself as the “White Man’s” candidate. Whites believed that a victory by Seymour’s Republican opponent, Ulysses S. Grant, former commander of the Union Army, would pave the way for racial equality, leading to the collapse of economic and political systems that favored whites in the South.After the Civil War ended, many impoverished whites faced increased economic hardship. Wealthier whites exploited their fears and blamed freed blacks as the cause of their ills. Newspapers owned by these elites were full of anti-Republican and racialized propaganda. Many poor whites perceived Reconstruction as a form of government occupation that disadvantaged them while favoring freed people. Conditions were ripe for dangerous rhetoric to turn lethal.Violence in St. Bernard Parish started a pre-election pro-Seymour rally on Sunday, October 25, 1868. As white marchers passed by Eugene Lock, a freedman, they yelled for him to “hurrah” for Seymour. Lock refused. Someone grabbed Lock to intimidate him into submission, but as Lock remained steadfast, the crowd grew increasingly agitated. One white man tried to stab Lock with a knife, while another shot at him, narrowly missing his target. Lock drew his own pistol and fired back, hitting the shoulder of the man who had fired at him. Outnumbered, Lock tried to escape, but was shot in the head and mortally wounded before finally being stabbed. As news of the altercation sped through the small community, men grabbed their arms and prepared for battle.Yet there was no battle, only a one-sided rampage by marauding whites. Throughout the week, armed white militias hunted freed people like Louis Wilson, as if for sport. In his testimony to an agent of the Freedmen’s Bureau shortly after the tragedy, Wilson said of the parish that he once called home: “This is such a cold place, I am afraid I will die here.”According to an 1868 report by the Freedmen’s Bureau and an 1869 report by the Louisiana General Assembly, white mobs broke into homes and shot residents at close range, conducted executions in the streets, and killed those who tried to intervene. They plundered former slave quarters and stole items they found useful, most notably registration papers. A black pregnant woman was hacked to death by men with bowie-knives next to the courthouse. A white police officer was murdered by mobs for trying to keep the peace. It was 19th-century terrorism.And it succeeded. While countless numbers of freed people fell victim to the violence, one white man, Pablo San Feliu, was killed by freed blacks in retaliation. Any legitimate supervisor of the presidential election was jailed, executed, or fled. Grant received only one vote in St. Bernard Parish as Seymour swept the state. According to historian John C. Rodrigue, “Republicans captured the presidency in 1868, but white terror carried the day in Louisiana.”Despite the federal investigation, no one was arrested for the killing of the freed people. Black survivors identified white neighbors as their assailants, but no justice was sought. Instead, more than 100 freed people were arrested by local authorities and vigilantes for the killing of Pablo San Feliu. Over time, the massacre faded into obscurity. To this day, its only physical reminder is the tombstone of Pablo San Feliu, located in St. Bernard Cemetery.The inaccuracies on San Feliu’s tombstone misrepresent the circumstances surrounding his death. The incorrect date suggests that it was erected a significant amount of time after the massacre, perhaps memorializing his death as if he were a martyr. The engraver referred to the freed people as “slaves.” Most importantly, by placing blame on carpetbaggers, the derogatory term applied to Northerners and other outsiders who had migrated to the South during Reconstruction, the inscription implies that San Feliu was an innocent murder victim.Nearly a decade after the massacre, Reconstruction officially ended. By 1877 Louisiana had returned to “home rule,” which meant that the black population was no longer protected by federal occupation. The new state government focused on suppression of black voters. The new state constitution allowed for arbitrary literacy tests and issued poll taxes, while also granting grandfather clauses that allowed white people to circumvent these obstacles to voting. By 1898, the black voting bloc had declined from 164,000 to a mere 1,342. By 1910, that number dropped to 730, less than a half-percent of eligible black men. Their political voice was silenced throughout Louisiana.A massacre of this magnitude deserves a place in history. In researching a book on the incident, I sought the assistance of locals who were aware of the ordeal, some from oral histories. Subsequently, I incorporated the story of the St. Bernard Parish Massacre into my teaching curriculum, so that students could be made aware of their community’s history and its relevance today. Other teachers also have the book in their classroom and discuss it with their students, examining how dangerous rhetoric can lead to deadly actions and the dire consequences of racist scapegoating.My students are often shocked when they learn about this chapter of their community’s history. But it provides opportunities to have open dialogue with one another about their roots, and to bring these conversations into their own homes.I have been criticized by some in the community for unearthing buried history. Some have claimed that the timing was inappropriate, that it would worsen existing racial tensions. However, the overwhelming majority of people in the community have been supportive and eager to know more.The progress that has brought my students closer together in the classroom can only be honored through a deeper understanding of history. These relationships epitomize how far race relations in Louisiana have advanced due to people pushing against barriers, from that lone man who voted for Grant in St. Bernard Parish to those who waged the nation’s first major bus boycott in Baton Rouge nearly a century later.However, the reversal of many gains made by black Louisianans after Reconstruction reminds us that these advances are not inherently linear or permanent. The continuing problems of mass incarceration, police brutality, and educational inequity underscore the effects of the disenfranchisement of huge swaths of the black population.Understanding complex historical events like the St. Bernard Parish Massacre shows how we can continue to bridge racial divides today. Communities should not hide from such history, but embrace it. Research more about this great American Tragedy and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event was The U.S. and a coalition of six Caribbean nations invaded the island nation of Grenada, 100 miles (160 km) north of Venezuela.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event was The U.S. and a coalition of six Caribbean nations invaded the island nation of Grenada, 100 miles (160 km) north of Venezuela. Codenamed Operation Urgent Fury by the U.S. military, it resulted in military occupation within a few days. It was triggered by the strife within the People’s Revolutionary Government which resulted in the house arrest and execution of the previous leader and second Prime Minister of Grenada Maurice Bishop, and the establishment of the Revolutionary Military Council with Hudson Austin as Chairman. The invasion resulted in the appointment of an interim government, followed by democratic elections in 1984.Today in our History – October 25, 1983, The United States invasion of Grenada began at dawn on 25 October 1983Grenada had gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1974. The communist New Jewel Movement seized power in a coup in 1979 under Maurice Bishop, suspending the constitution and detaining several political prisoners. In September 1983, an internal power struggle began over Bishop’s leadership performance.Bishop was pressured at a party meeting to share power with Deputy Prime Minister Bernard Coard. Bishop initially agreed, but later balked. He was put under house arrest by his own party’s Central Committee until he relented. When his secret detention became widely known, Bishop was freed by an aroused crowd of his supporters. A confrontation then ensued at military headquarters between Grenadian soldiers loyal to Coard and civilians supporting Bishop. Shooting started under still-disputed circumstances. At least 19 soldiers and civilians were killed on 19 October 1983 including Bishop, his partner Jacqueline Creft, two other cabinet ministers and two union leaders.The Reagan administration in the U.S. launched a military intervention following receipt of a formal appeal for help from the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States. In addition, the Governor-General of Grenada Paul Scoon secretly signaled he would also support outside intervention, but he put off signing a letter of invitation until 26 October. Reagan also acted due to “concerns over the 600 U.S. medical students on the island” and fears of a repeat of the Iran hostage crisis.The invasion began on the morning of 25 October 1983, just two days after the bombing of the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut. The invading force consisted of the US Army’s 1st and 2nd battalions of the 75th Ranger Regiment, the 82nd Airborne and the Army’s rapid deployment force, Marines, Army Delta Force, Navy SEALs, and ancillary forces totaling 7,600 troops, together with Jamaican forces and troops of the Regional Security System (RSS).The force defeated Grenadian resistance after a low-altitude airborne assault by Rangers and the 82nd Airborne on Point Salines Airport at the south end of the island, and a Marine helicopter and amphibious landing on the north end at Pearls Airport. Austin’s military government was deposed and replaced, with Scoon as Governor-General, by an interim advisory council until the 1984 elections.The invasion was criticized by many countries, including Canada. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher privately disapproved of the mission and the lack of notice that she received, but she publicly supported it. The United Nations General Assembly condemned it as “a flagrant violation of international law” on 2 November 1983 with a vote of 108 to 9.The date of the invasion is now a national holiday in Grenada called Thanksgiving Day, commemorating the freeing of several political prisoners who were subsequently elected to office. A truth and reconciliation commission was launched in 2000 to re-examine some of the controversies of the era; in particular, the commission made an unsuccessful attempt to find Bishop’s body, which had been disposed of at Austin’s order and never found. The invasion also highlighted issues with communication and coordination between the different branches of the American military when operating together as a joint force, contributing to investigations and sweeping changes in the form of the Goldwater-Nichols Act and other reorganizations. Research more about this great American Champion liberation effort. Share it with your babies and make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American pianist and singer-songwriter.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American pianist and singer-songwriter. One of the pioneers of rock and roll music, Domino sold more than 65 million records. Between 1955 and 1960, he had eleven Top 10 US pop hits. By 1955 five of his records had sold more than a million copies, being certified gold. The Associated Press estimates that during his career, the artist “sold more than 110 million records and the Grammy organization states that Domino landed 37 songs in the Top 40 on the Billboard Hot 100 throughout his career, including 11 that peaked inside the Top 10”.His humility and shyness may be one reason his contribution to the genre has been overlooked. The significance of his work was great however; Elvis Presley declared Domino to be “the real king of rock ‘n’ roll” and once announced that Domino “was a huge influence on me when I started out”.Four of Domino’s records were named to the Grammy Hall of Fame for their significance: “Blueberry Hill”, “Ain’t It A Shame”, “Walking to New Orleans” and “The Fat Man”. “The Fat Man” “is cited by some historians as the first rock and roll single and the first to sell more than 1 million copies” Today in our History – October 24, 2017 – Antoine Dominique Domino Jr. (February 26, 1928 – October 24, 2017), known as Fats Domino died.Antoine Domino Jr. was born and raised in New Orleans, Louisiana, the youngest of eight children born to Antoine Caliste Domino (1879–1964) and Marie-Donatille Gros (1886–1971). The Domino family was of French Creole background, and Louisiana Creole was his first language. Antoine was born at home with the assistance of his grandmother, a midwife. His name was initially misspelled as Anthony on his birth certificate. His family had recently arrived in the Lower Ninth Ward from Vacherie, Louisiana. His father was a part-time violin player who worked at a racetrack. He attended Howard University, leaving to start work as a helper to an ice delivery man. Domino learned to play the piano in about 1938 from his brother-in-law, the jazz guitarist Harrison Verrett. The musician was married to Rosemary Domino (née Hall) from 1947 until her death in 2008; the couple had eight children: Antoine III (1950-2015), Anatole, Andre (1952-1997), Antonio, Antoinette, Andrea, Anola, and Adonica. Even after his success he continued to live in his old neighborhood, the Lower Ninth Ward, until after Hurricane Katrina, when he moved to a suburb of New Orleans. By age 14, Domino was performing in New Orleans bars. In 1947, Billy Diamond, a New Orleans bandleader, accepted an invitation to hear the young pianist perform at a backyard barbecue. Domino played well enough that Diamond asked him to join his band, the Solid Senders, at the Hideaway Club in New Orleans, where he would earn $3 a week playing the piano. Diamond nicknamed him “Fats”, because Domino reminded him of the renowned pianists Fats Waller and Fats Pichon, but also because of his large appetite. Domino was signed to the Imperial Records label in 1949 by owner Lew Chudd, to be paid royalties based on sales instead of a fee for each song. He and producer Dave Bartholomew wrote “The Fat Man”, a toned down version of a song about drug addicts called “Junker Blues”; the record had sold a million copies by 1951. Featuring a rolling piano and Domino vocalizing “wah-wah” over a strong backbeat, “The Fat Man” is widely considered the first rock-and-roll record to achieve this level of sales. In 2015, the song would enter the Grammy Hall of Fame. Domino released a series of hit songs with Bartholomew (also the co-writer of many of the songs), the saxophonists Herbert Hardesty and Alvin “Red” Tyler, the bassist Billy Diamond and later Frank Fields, and the drummers Earl Palmer and Smokey Johnson. Other notable and long-standing musicians in Domino’s band were the saxophonists Reggie Houston, Lee Allen, and Fred Kemp, Domino’s trusted bandleader. While Domino’s own recordings were done for Imperial, he sometimes sat in during that time as a session musician on recordings by other artists for other record labels. Domino’s rolling piano triplets provided the memorable instrumental introduction for Lloyd Price’s first hit, “Lawdy Miss Clawdy”, recorded for Specialty Records on March 13, 1952 at Cosimo Matassa’s J&M Studios in New Orleans (where Domino himself had earlier recorded “The Fat Man” and other songs). Dave Bartholomew was producing Price’s record, which also featured familiar Domino collaborators Hardesty, Fields and Palmer as sidemen, and he asked Domino to play the piano part, replacing the original session pianist. Domino crossed into the pop mainstream with “Ain’t That a Shame” (mislabeled as “Ain’t It a Shame”) which reached the Top Ten. This was the first of his records to appear on the Billboard pop singles chart (on July 16, 1955), with the debut at number 14.A milder cover version by Pat Boone reached number 1, having received wider radio airplay in an era of racial segregation. In 1955, Domino was said to be earning $10,000 a week while touring, according to a report in the memoir of artist Chuck Berry. Domino eventually had 37 Top 40 singles, but none made it to number 1 on the Pop chart. Domino’s debut album contained several of his recent hits and earlier blues tracks that had not been released as singles, and was issued on the Imperial label (catalogue number 9009) in November 1955, and was reissued as Rock and Rollin’ with Fats Domino. The reissue reached number 17 on the Billboard Pop Albums chart. His 1956 recording of “Blueberry Hill”, a 1940 song by Vincent Rose, Al Lewis and Larry Stock (which had previously been recorded by Gene Autry, Louis Armstrong and others), reached number 2 on the Billboard Juke Box chart for two weeks and was number 1 on the R&B chart for 11 weeks. It was his biggest hit, selling more than 5 million copies worldwide in 1956 and 1957. The song was subsequently recorded by Elvis Presley, Little Richard, and Led Zeppelin. Some 32 years later, the song would enter the Grammy Hall of Fame. Domino had further hit singles between 1956 and 1959, including “When My Dreamboat Comes Home” (Pop number 14), “I’m Walkin'” (Pop number 4), “Valley of Tears” (Pop number ![]() , “It’s You I Love” (Pop number 6), “Whole Lotta Lovin'” (Pop number 6), “I Want to Walk You Home” (Pop number

, “It’s You I Love” (Pop number 6), “Whole Lotta Lovin'” (Pop number 6), “I Want to Walk You Home” (Pop number ![]() , and “Be My Guest” (Pop number