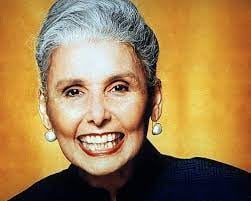

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was was an American singer, dancer, actress, and civil rights activist. Horne’s career spanned over 70 years, appearing in film, television, and theater. Horne joined the chorus of the Cotton Club at the age of 16 and became a nightclub performer before moving to Hollywood.Horne advocated for human rights and took part in the March on Washington in August 1963. Later she returned to her roots as a nightclub performer and continued to work on television, while releasing well-received record albums.She announced her retirement in March 1980, but the next year starred in a one-woman show, Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music, which ran for more than 300 performances on Broadway. She then toured the country in the show, earning numerous awards and accolades.Horne continued recording and performing sporadically into the 1990s, retreating from the public eye in 2000. Horne died of congestive heart failure on May 9, 2010, at the age of 92.Today in our History – June 30, 1917 – Lena Mary Calhoun Horne (June 30, 1917 – May 9, 2010) was born.Lena Horne was notable twentieth century woman associated with American entertainment industry and Civil Rights Movement. Before moving to Hollywood she became a nightclub performer at the age of sixteen. She was once blacklisted for her politically controversial role in the Red Scare.Lena Mary Calhoun Horne was born on June 30, 1917 in Bedford–Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. She is supposedly descended from the John C. Calhoun family. Her family is a mixture of European American, Native American, and African-American who belonged to middle-upper-class stature in the society.Her father was involved in gambling business and when she was three years old, he left his family. Horne’s mother was an actress with a black theatre troupe and traveled extensively, thus she was mainly raised by her grandparents. She was sent to live in Georgia at the age of five.After many years of travel with her mother, she lived with her uncle, Frank S. Horne, for two years. Upon their return to New York from Atlanta, Horne attended Girls High School in Brooklyn. Before earning her diploma certificate, she dropped out of the school.Later she moved in with her father in Pittsburg as she turned eighteen. She stepped into entertainment industry in 1933, and joined the chorus line of the Cotton Club. Afterwards, she recorded her first record release after joining Noble Sissle’s Orchestra.Subsequent to her separation from her first husband, Horne went on a tour with Charlie Barnet. Growing tired of frequent travel, she left the band. NBC featured her on popular jazz series The Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street as a lead vocalist.Moreover, Lena made appearance in a few musicals as well. The low-budget musical, The Duke is Tops was released in 1938. In 1942, she signed a long-term contract with a major Hollywood studio, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. She also worked in a popular radio series Suspense, playing the role of a nightclub singer.Her debut with MGM studio was in Panama Hattie (1942). Also she performed the title song of Stormy Weather. The film was loosely based on the life of Adelaide Hall (1943). Her other popular works include the musical, Cabin in the Sky. However, she was never offered the lead role because of strong racial discrimination still existing at the core of America. In fact, the films were twice edited because some of the states were against black artists on screen.Therefore, most of Lena’s appearances in the films were stand-alone sequences that sometimes seemed detached from the film entirely. One of the scenes featuring Horne taking a bubble bath and signing “Ain’t it the Truth” was removed from the movie as the film executives called it too “risqué”.Despite the extreme racial discrimination against blacks, Lena managed to be elected to serve on the Screen Actors Guild board of directors, which was a milestone for her. The Hollywood blacklisted her for her strong political views in 1950s.By then Horne was disappointed in Hollywood for its hypocrisy and unfair treatment of black artists. Thus she decided to head back to her nightclub career. She became one of the premier nightclub performers. In 1957, she released a live-recorded album, Lena Horne at the Waldorf-Astoria, which was received raving reviews and response from the listeners. The album became the biggest selling record by a female artist. Furthermore, Lena Horne was nominated for a Tony Award for “Best Actress in a Musical” as well.Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

Month: June 2021

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American paleoanthropologist.

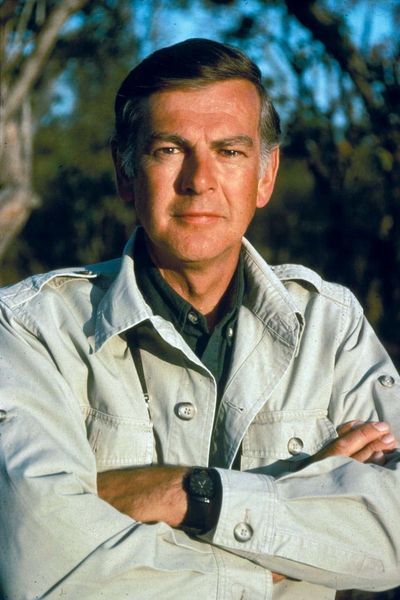

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American paleoanthropologist. He is known for discovering – with Yves Coppens and Maurice Taieb – the fossil of a female hominin australopithecine known as “Lucy” in the Afar Triangle region of Hadar, Ethiopia.Today in our history – June 28, 1943 – Donald Carl Johanson is born.Johanson was born in Chicago, Illinois to native parents, the nephew of wrestler Ivar Johansson. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign in 1966, and his master’s degree (1970) and PhD (1974) from the University of Chicago. At the time of the discovery of Lucy, he was an associate professor of anthropology at Case Western Reserve University.In 1981, he established the Institute of Human Origins in Berkeley, California which he later moved to Arizona State University in 1997. Johanson holds an honorary doctorate from Case Western Reserve University, and was awarded an Honorary Doctorate by Westfield State College in 2008. He is an atheist.Lucy was discovered in Hadar, Ethiopia on November 24, 1974, when Johanson, coaxed away from his paperwork by graduate student Tom Gray for a spur-of-the-moment survey, caught the glint of a white fossilized bone out of the corner of his eye, and recognized it as hominin.Forty percent of the skeleton was eventually recovered, and was later described as the first known member of Australopithecus afarensis. Johanson was astonished to find so much of her skeleton all at once. Pamela Alderman, a member of the expedition, suggested she be named “Lucy” after the Beatles’ song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” which was played repeatedly during the night of the discovery.A bipedal hominin, Lucy stood about three and a half feet tall; her bipedalism supported Raymond Dart’s theory that australopithecines walked upright. Johanson and his team concluded from Lucy’s rib that she ate a plant-based diet, and from her curved finger bones that she was probably still at home in trees.They did not immediately see Lucy as a separate species, but considered her an older member of Australopithecus africanus. The discovery, however, of several more skulls of similar morphology persuaded most palaeontologists to classify her as a species called afarensis.Johanson and Maitland A. Edey won a 1982 U.S. National Book Award in Science for the first popular book about this work, Lucy: The Beginnings of Humankind.AL 333, commonly referred to as the “First Family,” is a collection of prehistoric homininid teeth and bones of at least thirteen individuals that were also discovered in Hadar by Johanson’s team in 1975. Generally thought to be members of the species Australopithecus afarensis, the fossils are estimated to be about 3.2 million years old.· In 1976, Johanson received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.· In 1991, the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSICOP) awarded Johanson their highest honor, the In Praise of Reason award.· On October 19, 2014, Johanson gave the second annual Patrusky Lecture.· On October 24, 2014, Johanson accepted the “Emperor Has No Clothes” award at the Freedom From Religion Foundation 37th annual convention.·Asteroid 52246 Donaldjohanson, a target of the Lucy mission was named in his honor. The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on December 25, 2015 (M.P.C. 97569).Since 2013, Johanson has been listed on the Advisory Council of the National Center for Science Education. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American professional football player who was a fullback and linebacker for the Cleveland Browns in the All-America Football Conference (AAFC) and National Football League (NFL).

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American professional football player who was a fullback and linebacker for the Cleveland Browns in the All-America Football Conference (AAFC) and National Football League (NFL).He was a leading pass-blocker and rusher in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and ended his career with an average of 5.7 yards per carry, a record for running backs that still stands. A versatile player who possessed both quickness and size, Motley was a force on both offense and defense. Fellow Hall of Fame running back Joe Perry once called Motley “the greatest all-around football player there ever was”.Today in our History – June 27, 1999 – Marion Motley (June 5, 1920 – June 27, 1999) dies.Motley was also one of the first two African-Americans to play professional football in the modern era, breaking the color barrier along with teammate Bill Willis in September 1946, when the two played their first game for the Cleveland Browns.Motley grew up in Canton, Ohio. He played football through high school and college in the 1930s before enlisting in the military during World War II. While training in the U.S. Navy in 1944, he played for a service team coached by Paul Brown. Following the war, he went back to work in Canton before Brown invited him to try out for the Cleveland Browns, a team he was coaching in the newly formed AAFC.Motley made the team in 1946 and became a cornerstone of Cleveland’s success in the late 1940s. The team won four AAFC championships before the league dissolved and the Browns were absorbed by the more established NFL. Motley was the AAFC’s leading rusher in 1948 and the NFL leader in 1950, when the Browns won another championship.Motley and fellow black teammate Bill Willis contended with racism throughout their careers. Although the color barrier was broken in all major American sports by 1950, the men endured shouted insults on the field and racial discrimination off of it.”They found out that while they were calling us niggers and alligator bait, I was running for touchdowns and Willis was knocking the shit out of them,” Motley once said. “So they stopped calling us names and started trying to catch up with us.” Focused exclusively on winning, Brown did not tolerate racism within the team.Slowed by knee injuries, Motley left the Browns after the 1953 season. He attempted a comeback in 1955 as a linebacker for the Pittsburgh Steelers but was released before the end of the year. He then pursued a coaching career, but was turned away by the Browns and other teams he approached.He attributed his trouble finding a job in football to racial discrimination, questioning whether teams were ready to hire a black coach. Motley was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1968.Motley was born in Leesburg, Georgia and raised in Canton, Ohio, where his family moved when he was three years old.[4] After going to elementary and junior high schools in Canton, Motley attended Canton McKinley High School, where he played on the football and basketball teams. He was especially good as a football fullback, and the McKinley Bulldogs posted a win-loss record of 25–3 during his tenure there. The team’s three losses all came against Canton’s chief rivals, a Massillon Washington High School team led by coach Paul Brown.After he graduated, Motley enrolled in 1939 at South Carolina State College, a historically black school in Orangeburg, South Carolina. He transferred before his sophomore year to the University of Nevada, where he was a star on the football team between 1941 and 1943. As a punishing fullback for the Wolf Pack, Motley played against powerful West Coast teams including USF, Santa Clara, and St. Mary’s. He suffered a knee injury in 1943 and returned to Canton to work after dropping out of school.As United States involvement in World War II intensified, Motley joined the U.S. Navy in 1944 and was sent to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station. There he played for the Great Lakes Navy Bluejackets, a military team coached by Paul Brown, who was serving in the Navy during an extended leave from his job as head coach of The Ohio State University’s football team.[4] Motley played fullback and linebacker at Great Lakes, and was an important component of the team’s offense and defense. The highlight of his time at Great Lakes was a 39–7 victory over Notre Dame in 1945. Motley was eligible for discharge before the game – it was the final match of the season and the last military game of World War II – but he stayed on to play. Motley put up an impressive performance, thanks in part to Brown’s experimentation with a new play: a delayed handoff later called the draw play.After the war, Motley went back to Canton and began working at a steel mill, planning to return to Reno in 1946 to finish his degree. That summer, however, Paul Brown was coaching a team in the new All-America Football Conference (AAFC) called the Cleveland Browns. Motley wrote to Brown asking for a tryout, but Brown declined, saying he already had all the fullbacks he needed. At the beginning of August, however, Brown invited Bill Willis, another African-American star, to try out for the team at its training camp in Bowling Green, Ohio. Ten days later, Brown invited Motley to come, too. “I think they felt [Willis] needed a roommate,” Motley later said. “I don’t think they felt I’d make the team. I’m glad I was able to fool them.”Both Motley and Willis made the team and became two of the first African-Americans to play professional football in the modern era. The Los Angeles Rams of the National Football League had signed the only other black players in pro football earlier that year: Kenny Washington and Woody Strode. The four men broke football’s color barrier a seven months before Jackie Robinson was promoted from the Class AAA Montreal Royals to join the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Motley felt the Browns would likely be his only opportunity to make a career of football. “I knew this was the one big chance in my life to rise above the steel mill existence, and I really wanted to take it,” he said.Motley was signed to a contract worth $4,500 a year ($58,999 in 2019 dollars). With the Browns, he joined a potent offense led by quarterback Otto Graham, tackle and placekicker Lou Groza and receivers Dante Lavelli and Mac Speedie. He was a force to be reckoned with in the AAFC, and helped the team win every championship in the league’s four years of existence between 1946 and 1949.He had a combination of quickness and power – he was listed at 238 pounds – that helped him plow through tacklers. He was also an able pass blocker and played on defense as a linebacker. Motley rushed for an average of 8.2 yards per carry in his first season. His forte was the trap play, a scheme where a defensive lineman was allowed to come across the line of scrimmage unblocked, opening up space for Motley to run. He led the league in rushing in 1948 as the Browns posted a perfect 15–0 record. He was the AAFC’s all-time rushing leader when the league folded after the 1949 season and the Browns were absorbed into the more established National Football League (NFL). The Browns had a 47–4–3 overall regular-season win-loss-tie record during the AAFC years as Motley rushed for a total of 3,024 yards.Like other black players in the 1940s and 1950s, Motley faced racist attitudes both on and off the field. Paul Brown would not tolerate discrimination within the team; he wanted to win and would not let anything get in his way. Motley and Willis, however, were sometimes stepped on and called names during games. “Sometimes I wanted to just kill some of those guys, and the officials would just stand right there,” Motley said many years later. “They’d see those guys stepping on us and heard them saying things and just turn their backs. That kind of crap went on for two or three years until they found out what kind of players we were.” Motley and Willis did not travel to one game against the Miami Seahawks in the Browns’ early years after they received threatening letters. Another time in Miami, Motley and Willis were told they were not welcome at the hotel where the team was staying. Brown threatened to relocate the entire team, and the hotel’s management backed down.Attitudes toward race in America began to change after the war, which had caused social and political upheaval and prompted people to think about the future with more ambition and confidence. Although progress was slow and racially motivated hostility continued for many years, the color barrier was broken in all major sports by 1950. Many of Motley and Willis’s teammates on the Browns were used to playing with black players in college, where teams were integrated across most of the country. The presence of Motley and Willis, meanwhile, contributed to strong attendance at many of the Browns’ early games as large black audiences came to watch them. By one estimate, 10,000 black fans saw the Browns play their first game.Aided by Motley’s swiftness and size, the Browns won the NFL championship in 1950, their first season in the league. In October 1950, Motley set an NFL record that stood for more than 52 years when he averaged over 17 yards per rush against the Pittsburgh Steelers, with 188 yards on 11 carries. In December 2002, quarterback Michael Vick of the Atlanta Falcons rushed for 173 yards on 10 carries against the Minnesota Vikings, eclipsing Motley’s average. Motley also had a 69-yard rushing and 33-yard receiving touchdowns in the game. While Motley did not factor in the Browns’ championship game win against the Los Angeles Rams, he led the league in rushing with 810 yards in 1950 despite averaging fewer than 12 carries per game. He was a unanimous first-team All-Pro selection.By the 1951 season, Motley started to feel the physical effects of his hard-hitting, up-the-middle running style. He suffered a knee injury in training camp, and he was getting older; by the time the season was in full swing, he was 31. Motley only ran for 273 yards and one touchdown that year, an uncharacteristically low total. Despite Motley’s troubles, the Browns made the championship game again after winning the American Conference with an 11–1 record. Cleveland, however, lost the title game to the Rams, 24–17. Motley had just five carries and 23 yards.Motley’s knees continued to bother him in 1952. While he showed occasional signs of his old form that season, it became clear to the Browns’ coaching staff that he was no longer in his prime. Motley finished the year with 444 yards of rushing and 4.3 yards per carry, a career low. The Browns finished with an 8–4 record but still captured the conference title and secured another spot in the NFL championship game. Motley performed well in that matchup against the Detroit Lions, rushing for 95 yards. The Browns, however, lost 17–7.The 1953 season was no better for Motley, whose effectiveness was again limited by injury. Cleveland finished with an 11–1 record and faced Detroit in the championship for the second year in a row. As Motley’s production declined, the Browns relied on Otto Graham’s passing to Lavelli and receiver Ray Renfro, who also lined up as a running back. Motley did not participate in the championship game that year, another loss to the Lions.Motley thought he could come back and play a ninth season in 1954, and showed up to training camp to prove it. Paul Brown, however, thought otherwise. Dogged by injuries and 34 years old, Motley quit before the season began, after Brown said he would otherwise be cut from the team. “Marion realized that his knee was weak and did not feel that it was coming around,” Brown said at the time. “He was one of the truly fine fullbacks in his prime, the type that comes along once in a lifetime. I certainly never will forget some of his runs and I imagine Cleveland football fans feel the same.”Motley took the 1954 season off and attempted a comeback in 1955 after the Browns, who still had rights to Motley under his contract, traded him to the Pittsburgh Steelers for Ed Modzelewski. In Pittsburgh he played seven games as a linebacker, but the Steelers released him before the end of the season. In his eight years in the AAFC and NFL, Motley had rushed for 4,720 yards and averaged 5.7 yards per carry. His career rushing average is still an all-time record for running backs.After ending his playing career for good, Motley asked Brown about a coaching job with the team. Brown, however, rejected his overtures, saying Motley should instead look for work at a steel mill – the very career football was his ticket out of. Unable to find coaching opportunities in the NFL, he worked as a whisky salesman in the early 1960s. He got occasional scouting assignments from the Browns, but as the Civil Rights Movement began to coalesce in 1965, he issued a statement saying he had been refused a permanent coaching position by the team numerous times. He applied for a coaching job in 1964, he wrote, and was told that there were no vacancies. The Browns then hired Bob Nussbaumer as an assistant.”When I heard of the hiring of a new assistant, I began to wonder if the full reason is whether or not the time is ripe to hire a Negro coach in Cleveland on the professional level,” he wrote. Art Modell, the Browns’ owner, responded by saying the team filled its coaching positions based on ability and experience, not race. “We are represented by scouts at every major Negro school. And we now have 12 Negroes signed for the 1965 season,” he said.Motley asked Otto Graham for a job with the Washington Redskins when Graham was head coach there in the late 1960s, but he was again turned away. Motley also signed on to coach an all-girl professional football team called the Cleveland Dare Devils in 1967. By 1969, the team had only played a few exhibition games as Cleveland theatrical agent Syd Freedman struggled to drum up interest in a women’s league. Later in life, Motley worked for the U.S. postal service in Cleveland, Harry Miller Excavating Suffield, Ohio, the Ohio Lottery and for the Ohio Department of Youth Services in Akron. He died in 1999, twenty-two days after his 79th birthday, of prostate cancer.In 1968, Motley became the second black player voted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, located in his hometown of Canton. Having played successfully as a fullback and pass blocker on offense and as a linebacker on defense, he is seen as one of the best all-around players in football history. Blanton Collier, an assistant who took over as the team’s head coach after Paul Brown’s firing in 1963, said Motley “had no equal as a blocker. He could run with anybody for 30 yards or so. And this man was a great, great linebacker.”Most of Motley’s runs were trap plays up the middle, but he had the speed to run outside. “There’s no telling how much yardage I might have made if I ran as much as some backs do now,” he once said. Running back Jim Brown surpassed Motley’s rushing records in the early 1960s, but many of Motley’s coaches and fellow players regarded Motley as the better player, in part because of his strength as a blocker. “There is no comparison between Jim Brown and Marion Motley,” Graham said at a luncheon in Canton in 1964. “Motley was the greatest all-around fullback.”In his books The Thinking Man’s Guide to Pro Football and The New Thinking Man’s Guide To Pro Football, football writer Paul Zimmerman of Sports Illustrated called Motley the best player in the history of the sport. He was named to the NFL’s 75th Anniversary All-Time Team in 1994.In November 2019, Motley was selected as one of the twelve running backs on the NFL 100 All-Time Team. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American jazz trumpeter.

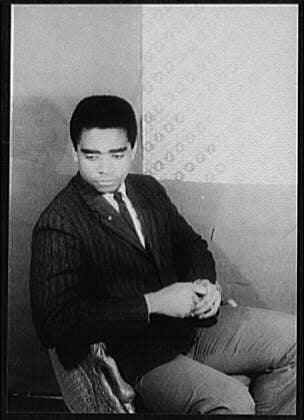

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American jazz trumpeter. He died at the age of 25 in a car accident, leaving behind four years’ worth of recordings. His compositions “Sandu”, “Joy Spring”, and “Daahoud” have become jazz standards. Brown won the Down Beat magazine Critics’ Poll for New Star of the Year in 1954; he was inducted into the DownBeat Hall of Fame in 1972.Today in our History – June 26, 1956 – Clifford Benjamin Brown (October 30, 1930 – June 26, 1956) dies.Brown was born into a musical family in Wilmington, Delaware. His father organized his four sons, including Clifford, into a vocal quartet. Around age ten, Brown started playing trumpet at school after becoming fascinated with the shiny trumpet his father owned. At age thirteen, his father bought him a trumpet and provided him with private lessons. In high school, Brown received lessons from Robert Boysie Lowery and played in “a jazz group that Lowery organized”. He making trips to Philadelphia.Brown briefly attended Delaware State University as a math major before he switched to Maryland State College. His trips to Philadelphia grew in frequency after he graduated from high school and entered Delaware State University. He played in the fourteen-piece, jazz-oriented Maryland State Band. In June 1950, he was injured in a car accident after a performance. While in the hospital, he was visited by Dizzy Gillespie, who encouraged him to pursue a career in music. Injuries restricted him to playing the piano.Brown was influenced and encouraged by Fats Navarro. His first recordings were with R&B bandleader [Chris Powell. He worked with Art Blakey, Tadd Dameron, Lionel Hampton, J. J. Johnson, and before forming a band with Max Roach. Brown’s trumpet was partnered with Harold Land’s tenor saxophone. After Land left in 1955, Sonny Rollins joined and remained a member of the group for the rest of its existence.Brown stayed away from drugs and was not fond of alcohol. Rollins, who was recovering from heroin addiction, said that “Clifford was a profound influence on my personal life. He showed me that it was possible to live a good, clean life and still be a good jazz musician.”In June 1956, Brown and Richie Powell embarked on a drive to Chicago for their next appearance. Powell’s wife Nancy was at the wheel so that Clifford and Richie could sleep. While driving at night in the rain on the Pennsylvania Turnpike, west of Bedford, Pennsylvania|Bedford, she is presumed to have lost control of the car, which went off the road, killing all three in the resulting crash. Brown is buried in Mt. Zion Cemetery, in Wilmington, Delaware.On June 26, 1954, in Los Angeles, Brown married Emma LaRue Anderson (1933–2005), who he called “Joy Spring”. The two had been introduced by Max Roach. They actually celebrated their marriage vows three times, partly because their families were on opposite coasts and partly because of their differing religions – Brown was Methodist and Anderson was Catholic. They were first married in a private ceremony June 26, 1954, in Los Angeles (on Anderson’s 21st birthday). They again celebrated their marriage in a religious setting on July 16, 1954 – the certificate being registered in Los Angeles County – and a reception was held at the Tiffany Club where the Art Pepper/Jack Montrose Quintet had been replaced a few days earlier by the Red Norvo Trio with Tal Farlow and Red Mitchell. Anderson’s parish priest followed them to Boston, where on August 1, 1954 they performed their marriage ceremony at Saint Richards Church in the Roxbury, Boston|Roxbury neighborhood.His nephew, drummer Rayford Griffin (né Rayford Galen Griffin; born 1958), modernized Brown’s music on his 2015 album Reflections of Brownie. Brown’s grandson, Clifford Benjamin Brown III (born 1982), plays trumpet on one of the tracks, “Sandu”. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – LIF – Today’s American Champion is an American operatic tenor, and was the first African-American tenor to perform a leading role at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City.

GM – LIF – Today’s American Champion is an American operatic tenor, and was the first African-American tenor to perform a leading role at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City.Today in our History – June 24, 1954 – George Irvin Shirley marries Gladys Lee Ishop.Shirley was born in Indianapolis, Indiana, and raised in Detroit, Michigan. He earned a bachelor’s degree in music education from Wayne State University in 1955 and then was drafted into the Army, where he became the first Black member of the United States Army Chorus. He was also the first African American hired to teach music in Detroit high schools.After continuing voice studies with Therny Georgi, he moved to New York and began his professional career as a singer. His debut was with a small opera group in Woodstock as Eisenstein in Strauss’s Die Fledermaus in 1959, and his European debut in Italy as Rodolfo in Puccini’s La bohème.In 1960, at 26, he won a National Arts Club scholarship competition, and the following April he was the first Black singer to win the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions scholarship competition. Shirley is the first Black tenor and the second Black male to sing leading roles for the Metropolitan Opera. He sang there for 11 seasons.Shirley has also appeared at The Royal Opera, London; the Deutsche Oper Berlin; the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires; the Dutch National Opera in Amsterdam; Opéra de Monte-Carlo; the New York City Opera; the Scottish Opera; the Lyric Opera of Chicago; the Washington National Opera; the Michigan Opera Theatre; the San Francisco Opera; and the Santa Fe Opera and Glyndebourne Festival summer seasons, as well as with numerous orchestras in the United States and Europe. He has sung more than 80 roles.He was on the faculty of the University of Maryland from 1980 to 1987, when he moved to the University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre & Dance, where he was Director of the Vocal Arts Division. He currently serves as the Joseph Edgar Maddy Distinguished University Professor of Music, and still maintains a studio at the schoolShirley’s recording of Ferrando in Mozart’s Così fan tutte won a Grammy Award. He has three times been a master teacher in the National Association of Teachers of Singing Intern Program for Young NATS Teachers, and taught for ten years at the Aspen Music Festival and School. Shirley produced a series of programs for WQXR-FM radio in New York on Classical Music and the Afro-American and hosted a four-program series on WETA-FM radio in Washington, D.C. called Unheard, Unsung. Shirley has been awarded honorary degrees by Wilberforce University, Montclair State College, Lake Forest College, and the University of Northern Iowa. He is a National Patron of Delta Omicron, an international professional music fraternity.Shirley is a member of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia and was named a Signature Sinfonian in 2013, an award recognizing exceptional accomplishment in that brother’s chosen field. In 2015, Shirley received the National Medal of Arts, bestowed upon him by US President Barack Obama, and in 2016, he was a recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Opera Association at their annual conventionShirley was born on April 18, 1934 in Indianapolis, Indiana. At age four Shirley began performing at church in a musical trio with his parents, Daisy and Irving Shirley, and at age five he won a local talent competition. Irving Shirley went to work for the auto industry in Detroit, Michigan, moving the family there in 1940.During his school years Shirley studied voice at Detroit’s Northern High School, and then won a scholarship to Wayne State University. After graduating in 1955 with a Bachelor of Science degree in Music Education, Shirley became the first black high school music teacher in Detroit, Michigan. Shirley married Gladys Lee Ishop on June 24, 1956, the same year he was drafted into the Army. The couple had two children, Olwyn and Lyle.Before making his debut with the Met in October 1961, Shirley continued his musical education at the Tanglewood Music Center, and at Boris Goldovsky’s opera summer school. His first public operatic debut in 1959 was with a small opera company in Woodstock, New York, where Shirley sang the leading role of Eisenstein in Johann Strauss’s Die Fledermaus. The next year Shirley won the American Opera Auditions and was invited to sing in Italy. He made his European debut in the fall of 1960 at Milan’s Teatro Nuovo in the role of Rodolfo in Puccini’s La Bohème.In a music career that lasted more than 50 years, Shirley sang leading roles in over 80 operas at major opera houses all over the world. In 1968 Shirley received a Grammy Award for singing the role of Ferrando in Mozart’s opera Così fan tutte, a recording that also featured opera greats Leontyne Price, Sherrill Milnes, and Tatiana Troyanos.In 1980 Shirley was asked to teach voice at the University of Maryland, where in 1985 he received their Distinguished Scholar-Teacher Program award. Upon moving back to his hometown of Detroit in 1987, Shirley became a professor of voice at the University of Michigan, a position he held until his retirement in 2007.During his career Shirley received numerous other awards, among which have been the “Lift Every Voice” Legacy Award from the National Opera Association (2003), honorary degrees from The New England Conservatory of Music, Lake Forest College, the University of Northern Iowa, Montclair State College, and Wilberforce University in Ohio, and the Doctor of Humane Letters Degree from Wayne State University (2013).The George Shirley Voice Scholarship was established at the University of Michigan in 2008. As the Joseph Edgar Maddy Distinguished Emeritus Professor of Music (Voice) School at the University of Michigan, George Shirley is still teaching master classes and offering individual classes. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a track and field athlete who was the first African American to win an Olympic gold medal in an individual event: the running long jump at the 1924 Paris Summer games.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a track and field athlete who was the first African American to win an Olympic gold medal in an individual event: the running long jump at the 1924 Paris Summer games.Today in our History – June 23, 1924 – William DeHart Hubbard (November 25, 1903 – June 23, 1976) was born.William DeHart Hubbard was the first African American to win a gold medal at the Olympics as an individual, placing first in the running long jump. Hubbard was born on November 25, 1903, in Cincinnati, Ohio and attended Walnut Hills High School in that city. Hubbard’s achievements on the track and in the classroom caught the attention of a University of Michigan alumnus, Lon Barringer, who saw his times posted in a Cincinnati newspaper. With the encouragement and recruiting of Barringer and other alums, Hubbard decided that he would attend the University of Michigan and run track.As an African American, attending the University of Michigan and running track there was an achievement enough of its own. In Hubbard’s senior class, only eight out of the 1,456 graduating students were African American. He excelled in academics, graduating with honors in 1927, and on the track, setting records and winning numerous championships for the Wolverines. As a freshman, Hubbard was not allowed to run Varsity track. His sophomore year was mediocre but he began to break records in his junior year. He helped win Big Ten championships in the 100-meter dash, running a time of 9.8 seconds, and the long jump, jumping 24 feet 10 and ¾ inches. With performances like that, DeHart won a spot on the 1924 Olympic team, beating Edward Gourdin (then the world record holder) at trials at Harvard University to seal his spot to represent the United States at the Olympics in Paris, France.Hubbard struggled initially at the Olympics. On his sixth and final jump match he bruised his heel and committed a foul for stepping too far over the line. However, coming into his last jump at full speed, he leaped 24 feet 5 and ½ inches, and became the first African American to win a gold medal as an individual in the Olympics.Going into his senior year at Michigan Hubbard competed in sprints, hurdles, and the long jump, helping the Wolverines win Big Ten titles in indoor and outdoor meets. He also tied the world record in the 100-meter dash at 9.6 seconds, and beat the world record in the long jump, jumping 25 feet, 10 and 3/8 inches.After graduating from the University of Michigan, Hubbard worked at a number of different jobs. He was a supervisor at the Department of Colored Work for the Cincinnati Public Recreation Commission, and was a manager of a housing project in Cincinnati, before moving to Cleveland, Ohio. He retired in Cleveland after working for the Federal Public Housing Authority. William DeHart Hubbard died on June 23, 1976, in Cleveland, Ohio. He subsequently set a long jump world record of 25 feet 10 3⁄4 inches (7.89 m) at Chicago in June 1925 and equaled the world record of 9.6 seconds for the 100-yard dash at Cincinnati, Ohio a year later.He attended and graduated from Walnut Hills High School in Cincinnati, graduated with honors from the University of Michigan in 1927 where he was a three-time National Collegiate Athletic Association champion (1923 & 1925 outdoor long jump, 1925 100-yard dash) and seven-time Big Ten Conference champion in track and field (1923 & 1925 indoor 50-yard dash, 1923, 1924, & 1925 outdoor long jump, 1924 & 1925 outdoor 100-yard dash). His 1925 outdoor long jump of 25 feet 10 1⁄2 inches (7.89 m) stood as the Michigan Wolverines team record until 1980, and it still stands second. His 1925 jump of 25 feet 3 1⁄2 inches (7.71 m) stood as a Big Ten Championships record until Jesse Owens broke it on with what is now the current record of 26 feet 8 1⁄4 inches (8.13 m) in 1935.Upon college graduation, he accepted a position as the supervisor of the Department of Colored Work for the Cincinnati Public Recreation Commission. He remained in this position until 1941. He then accepted a job as the manager of Valley Homes, a public housing project in Cincinnati. In 1942 he moved to Cleveland, Ohio where he served as a race relations adviser for the Federal Housing Authority. He retired in 1969. He died in Cleveland in 1976. Hubbard was posthumously inducted into the University of Michigan Hall of Honor in 1979; he was part of the second class inducted into the Hall of Honor. He was a member of the Omega Psi Phi fraternity. In addition to participating in track and field events, Hubbard also was an avid bowler. He served as the president of the National Bowling Association during the 1950s. He also founded the Cincinnati Tigers, a professional baseball team, which played in the Negro American League. In 1957, Hubbard was elected to the National Track Hall of Fame. In 2010, the Brothers of Omega Psi Phi, Incorporated, PHI Chapter established a scholarship fund honoring William DeHart Hubbard; the fund is endowed through the University of Michigan and donations can be forwarded to the University of Michigan, The William DeHart Hubbard Scholarship Fund. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event is not talked about that much because not many records are kept about it but today we will gain some knowledge of this.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event is not talked about that much because not many records are kept about it but today we will gain some knowledge of this.For USS Constitution, which carried approximately 450 men, seven to 15 percent of the crew translates to approximately 32 to 68 black or multiracial sailors per cruise during the War of 1812. Unfortunately, discovering just who these men were is extremely difficult. The USS Constitution Museum has collected substantial demographic and biographical information for over 200 of the approximately 1,168 sailors assigned to Constitution during the War of 1812. Unfortunately, of those 200 or so sailors, only three are identifiable as black.June 16, 1812 – One is Jesse Williams, a native of Pennsylvania who joined USS Constitution as an ordinary seaman in Boston.65 Muster Roll(s), USS Constitution, T829, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. Williams stood five feet, six inches tall and was stoutly built with a round face and black hair.6666 Dartmoor: Public Record Office, Adm 103/87-91, The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, United Kingdom and General Entry Books of American Prisoners of War at Quebec, RG8, C series, 694A-B, Library and Archives Canada, Ottowa, Canada. During Constitution’s battle with HMS Guerriere, Williams served as the first sponger for the number three long gun on the gun deck. He also served aboard during the battle with HMS Java on December 29, 1812. Williams was transferred to the Great Lakes in April 1813, where he was wounded in battle and received a share of prize money.6767 Muster Roll(s), USS Constitution, T829. Later, while serving aboard USS Scorpion, Williams was captured by the British and sent to Dartmoor Prison in England.6868 Dartmoor: Public Record Office, Adm 103/87-91. After being released at the end of the war, Williams made the rank of able seaman in December 1814. He left the navy the following year.6969 Muster Roll(s), USS Constitution, T829. Six years later, in recognition of his service on the Lakes, the state of Pennsylvania awarded Williams, as well as other service members from the state, a silver medal.7070 “Correspondence Relating to Medallists, 1812-1814,” Pennsylvania Archives, Sixth Series IX (ca. 1734-1847): 248-304.Another man, James Bennett, had a similar story. Bennett was born free in Duck Creek Crossroads, Delaware in about 1782. In 1810, he, along with his sister, Mary Williams, traveled to Philadelphia to obtain a seaman’s protection certificate to serve as written proof of his American citizenship while at sea. The certificate, made out to Bennett from Philadelphia Alderman Alexander Tod, includes a detailed descrip18tion of the sailor. Alderman Tod wrote:“Negroe, born free — five feet 11 7/8 inches high, with his shoes, Black complexion, Black hair, 28 years of age, marked with scar over his right eye brow, mark of inoculation on his left arm, mark by a burn on his right elbow, mark on the palm of his left hand by being laid open, left knee crooked.”7171 Tyrone G. Martin, “Ship’s Company,” Captain’s Clerk, last modified September 30, 2019, http://captainsclerk.info/.Bennett enlisted in the U.S. Navy in April 1811 and joined Constitution’s crew as an ordinary seaman, promptly becoming a member of the carpenter’s crew.7272 Muster Roll(s), USS Constitution, T829. He sailed on a diplomatic voyage to France and Holland, and remained aboard for the first two cruises of the War of 1812. During the victorious battles over HMS Guerriere on August 19, 1812 and HMS Java on December 29, 1812, Bennett, with the rest of the carpenter’s crew, labored deep in the ship’s hold to plug holes made by enemy shot. For his effort he received a portion of the $100,000 in prize money awarded to the crew in addition to his monthly pay. When the ship returned to Boston, Bennett was drafted to the Great Lakes to serve under Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry at the Battle of Lake Erie. Unfortunately, Bennett suffered a mortal wound during battle and never made it home.7373 Ibid. In 1857, his wife, Sarah Bennett, appealed to Congress for his back pay and prize money, but her plea was rejected.7474 War of 1812 Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, ca. 1871-ca.1900, RG15, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.The third black sailor identified from Constitution’s War of 1812 crew is David Debias. Debias was born in Boston on August 9, 1806. He lived with his parents on Belknap Street (now Joy Street) on the north slope of Beacon Hill.7575 Thomas Falconer, letter to Secretary of the Navy, March 16, 1838, M124, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. On December 17, 1814, Debias’ father entered him on board Constitution.7676 Muster Roll(s), USS Constitution, T829.At eight years old, Debias was rated a boy — a rank designated for the least skilled, though not necessarily the youngest, sailors — and assigned as servant to Master’s Mate Nathaniel G. Leighton. He was aboard for the battle with HMS Cyane and HMS Levant on the night of February 20, 1815, and was subsequently placed on the captured Levant, along with Master’s Mate Leighton, as part of the prize crew. However, Levant was soon recaptured by a British squadron on its way back to the 19United States, and Debias was imprisoned in Barbados until May. Upon his release, he returned home and was reunited with his family. Debias was discharged and paid off in July 1815.77 In 1821, he joined the U.S. Navy again, sailing once more on Constitution to the Mediterranean Sea.78 He returned to the United States in 1824 and joined the merchant service.79In 1838, Debias left his ship in Mobile, Alabama, started walking north, and was picked up as a runaway slave in Winchester, Mississippi.80 His plight caught the attention of a local lawyer named Thomas Falconer, who was convinced that Debias was a free man. Falconer wrote to Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson seeking proof of Debais’ status. Falconer’s letter to Dickerson pleads Debias’ case, describing his service to his country and requesting Debias’ naval records.81 Dickerson complied with Falconer’s request and sent proof of Debias’ service, but no confirmed records of his fate have yet been found.82 Unfortunately, Debias’ story, much like the story of many black sailors from the War of 1812, is incomplete. Reserach more about this great American event and shear it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM –FBF – Today’s American Champion was an author, abolitionist, and minister.

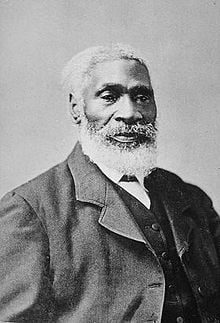

GM –FBF – Today’s American Champion was an author, abolitionist, and minister. Born into slavery, in Port Tobacco, Charles County, Maryland, he escaped to Upper Canada (now Ontario) in 1830, and founded a settlement and laborer’s school for other fugitive slaves at Dawn, near Dresden, in Kent County, Upper Canada, of Ontario. Henson’s autobiography, The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself (1849), is believed to have inspired the title character of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). Following the success of Stowe’s novel, Henson issued an expanded version of his memoir in 1858, Truth Stranger Than Fiction.Father Henson’s Story of His Own Life (published Boston: John P. Jewett & Company, 1858). Interest in his life continued, and nearly two decades later, his life story was updated and published as Uncle Tom’s Story of His Life: An Autobiography of the Rev. Josiah Henson Today in our History – June 15 – Josiah Henson (June 15, 1789 – May 5, 1883) died.Josiah Henson was born on a farm near Port Tobacco, Charles County, Maryland on a plantation owned by Francis Newman where Henson experienced slave atrocities. Henson’s father was enslaved by Francis Newman whereas Josiah Henson, his mother and siblings were enslaved by Dr. Josiah McPherson.When he was a boy, his father was punished for standing up to a slave overseer, for which he received one hundred lashes. In addition, his right ear was nailed to the whipping post and then cut off. His father was sold away to Alabama. Josiah Henson experienced hardships and sufferings at the hads of his masters as well, including having his arms broken and an injury to his back.Following his family’s master’s death, young Josiah was separated from his mother, brothers, and sisters. At the slave auction, Henson’s siblings were sold first. His mother was bought by Issac Riley of Montgomery County and when she pleaded to her new owner to purchase Josiah Henson, Riley responded by hitting and kicking her. Josiah Henson was sold to Adam Robb of Rockville, Montgomery County. Adam Robb encountered Issac Riley and struck a deal which resulted in Henson being sold to Riley and was reunited with his mother. Josiah Henson became very ill. His mother pleaded with her owner, Isaac Riley, and Riley greed to buy back Henson so she could at least have her youngest child with her, on the condition that he would work in the fields.Riley would not regret his decision, for Henson rose in his owners’ esteem, and was eventually entrusted as the supervisor of his master’s farm, located in Montgomery County, Maryland (in what is now North Bethesda). In 1825, Mr. Riley fell onto economic hardship and was sued by a brother-in-law. Desperate, he begged Henson, with tears in his eyes, to promise to help him. Duty bound, Henson agreed. Mr. Riley then told him that he needed to take his eighteen slaves to his brother in Kentucky by foot. They arrived in Daviess County, Kentucky, in the middle of April 1825 at the plantation of Mr. Amos Riley. In September 1828, Henson returned to Maryland in an attempt to buy his freedom from Issac Riley. He tried to buy his freedom by giving his master $350, which he had saved up, and a note premising a further $100. Originally, Henson only needed to pay the extra $100 by note. Mr. Riley, however, added an extra zero to the paper and changed the fee to $1000. Cheated of his money, Henson returned to Kentucky and then escaped to Kent County, Upper Canada in 1830, after learning that he might be sold again. In the last of these attempts to attain freedom, Amos Riley, agreed to give Josiah his freedom in exchange for $300. Josiah raised the money only to find that his master had raised the fee. Soon after, Henson learned that Riley planned to sell him in New Orleans, Louisiana, separating him from his wife and four children. When he found this out, Henson became determined to escape to Canada and freedom. He took his family with him, including his wife and their children to start the new life northward. After convincing his wife to escape with him, Henson’s wife created a knapsack large enough to carry both of their smallest children and the eldest two would accompany his wife. The Henson family left Kentucky traveling through the night and sleeping in the woods throughout the day. They crossed into Indiana then into Cincinnati where they were safely welcomed in a home for a few days. As the Henson family was crossing Hull’s Road in Ohio, Josiah’s wife fainted out of exhaustion. As they continued on, they encountered Indians and were reinvigorated with food and rest. After crossing a lake in Ohio, Josiah encountered Captain Burnham, a ship captain, who agreed to transport the Henson family to Buffalo, New York and there they would cross the river into Canada.Upon stepping foot into Canada, Josiah Henson described the ecstatic feelings of liberation by throwing himself onto the ground and rejoicing with his family. On October 28, 1830, Josiah Henson became a liberated man. Upper Canada had become a refuge for slaves who had escaped from the United States after 1793, when Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe passed “An Act to prevent the further introduction of Slaves, and limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude within this Province”. The legislation did not immediately end slavery in the colony, but it did prevent the importation of slaves. As a result, any U.S. slave who set foot in what would eventually become Ontario was free. By the time Henson arrived, others had already made Upper Canada their home, including Black Loyalists from the American Revolution and refugees from the War of 1812. In 1833, slavery was outlawed in the British Empire. At this time, Canadians were still a part of colonial British Canada.Josiah Henson first worked on farms near Fort Erie, then Waterloo, moving with friends to Colchester in 1834 to set up a Black settlement on rented land. After earning enough, Henson was able to send his eldest son Tom to school who then taught Josiah how to read. Henson became literate and was able to lead the growing community of fugitive slaves in Canada.Through contacts and financial assistance there, he was able to purchase 200 acres (0.81 km2) in Dawn Township, in neighbouring Kent County, to realize his vision of a self-sufficient community. The Dawn Settlement eventually reached a population of 500[citation needed] at its height, exporting black walnut lumber to the United States and Britain. Henson purchased an additional 200 acres (0.81 km2) next to the Settlement, where his family lived. Henson also became an active Methodist preacher and spoke as an abolitionist on routes between Tennessee and Ontario. He also served in the Canadian Army as a military officer, having led a Black militia unit in the Canadian Rebellion of 1837. In 1838, Henson and the militia successfully captured the rebel ship Anne, cutting off their supply lines to southwestern Upper Canada. Though many residents of the Dawn Settlement returned to the United States after slavery was abolished there, Henson and his wife continued to live in Dawn for the rest of their lives.Henson became the spiritual leader within the community and embarked on several trips to the United States and Great Britain where he met with Queen Victoria. While in Britain, Josiah publicly spoke to audiences and raised funds for the community back in Canada. Henson conducted several trips back to Kentucky to guide other slaves to freedom.· The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself. 1849· Truth Stranger Than Fiction. Father Henson’s Story of His Own Life. 1858· Uncle Tom’s Story of His Life: An Autobiography of the Rev. Josiah Henson. 1878.Josiah Henson is the first black man to be featured on a Canadian stamp. He was also recognized by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada in 1999 as a National Historic Person. A federal plaque to him is located in the Henson family cemetery, next to Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site.A 2018 documentary titled Redeeming Uncle Tom: The Josiah Henson Story covers his life.The actual cabin in which Josiah Henson and other slaves were housed no longer exists.[15] The Riley family house, however, remains and is currently in a residential development in Rockville, Montgomery County, Maryland. After having remained in the hands of private owners for nearly two centuries, on January 6, 2006, the Montgomery Planning Board agreed to purchase the property and the acre of land on which it stands for $1,000,000.The house was opened to the public for one weekend in 2006. As of March 2009, the site has received an additional $50,000 from the Maryland state Board of Public Works for the planning and design phase of a multiyear restoration project. An additional $100,000 may come from the Federal government that would go towards restoration and planning. The site was planned to be opened permanently to the public in 2012, until then there were guided tours four times a year.In 2018, Josiah Henson Park, in North Bethesda, Maryland, contains the Riley/Bolton house, where Henson’s owner lived. The Montgomery County park site (construction/restoration) is not yet completed. As of 2018, it is open for group tours and on “special occasions”. “Ongoing archaeological excavations seek to find where Josiah Henson may have lived on the site.”Located near Dresden, Ontario, in Canada, Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site includes the cabin that was home to Josiah Henson during much of his time in the area, from 1841 until his death in 1883. The five-acre complex includes Henson’s cabin, an interpretive centre about Henson and the Dawn settlement, an exhibit gallery about the Underground Railroad, outbuildings, a 19th-century historic house, a cemetery and a gift shop.Harriet Beecher Stowe published the anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, in 1852. During the first year of being published, over one million copies were sold in Great Britain and the United States, which led it to become the best selling novel of the 19th-century. Stowe had the intentions of this novel being published when she wrote it; she had taken out a copyright for Uncle Tom’s Cabin before it appeared in The National Era.Stowe knew in order for her novel to play a pivotal role in the development of American cultur; focusing on racism, slavery, and gender, she had to make a larger impact than the abolitionists of the press. Established by a Russian journalist, Stowe used “defamiliarization” to create new perspectives when it came to the issues she focused on, by presenting them in unfamiliar ways so people can see it in a different way. This helped support her endorsing domestic family values of all races, and presented the prejudicial assumption options about cultural differences in the 19th-century. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies, Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American abolitionist and author.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American abolitionist and author. She came from the Beecher family, a famous religious family, and is best known for her novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), which depicts the harsh conditions for enslaved African Americans. The book reached millions as a novel and play, and became influential in the United States and Great Britain, energizing anti-slavery forces in the American North, while provoking widespread anger in the South. She wrote 30 books, including novels, three travel memoirs, and collections of articles and letters. She was influential for both her writings and her public stances and debates on social issues of the day.Today in our History – June 14, 1811 – Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe ( June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was born.Harriet Elisabeth Beecher was born in Litchfield, Connecticut, on June 14, 1811. She was the sixth of 11 children born to outspoken Calvinist preacher Lyman Beecher. Her mother was his first wife, Roxana (Foote), a deeply religious woman who died when Stowe was only five years old. Roxana’s maternal grandfather was General Andrew Ward of the Revolutionary War. Her siblings included a sister, Catharine Beecher, who became an educator and author, as well as brothers who became ministers: including Henry Ward Beecher, who became a famous preacher and abolitionist, Charles Beecher, and Edward Beecher.Harriet enrolled in the Hartford Female Seminary run by her older sister Catharine.There she received something girls seldom got, a traditional academic education, with a focus in the Classics, languages, and mathematics. Among her classmates was Sarah P. Willis, who later wrote under the pseudonym Fanny Fern.In 1832, at the age of 21, Harriet Beecher moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, to join her father, who had become the president of Lane Theological Seminary. There, she also joined the Semi-Colon Club, a literary salon and social club whose members included the Beecher sisters, Caroline Lee Hentz, Salmon P. Chase (future governor of Ohio and Secretary of the Treasury under President Lincoln), Emily Blackwell and others.Cincinnati’s trade and shipping business on the Ohio River was booming, drawing numerous migrants from different parts of the country, including many escaped slaves, bounty hunters seeking them, and Irish immigrants who worked on the state’s canals and railroads.In 1829 the ethnic Irish attacked blacks, wrecking areas of the city, trying to push out these competitors for jobs. Beecher met a number of African Americans who had suffered in those attacks, and their experience contributed to her later writing about slavery. Riots took place again in 1836 and 1841, driven also by native-born anti-abolitionists.[citation needed]Harriet was also influenced by the Lane Debates on Slavery. The biggest event ever to take place at Lane, it was the series of debates held on 18 days in February 1834, between colonization and abolition defenders, decisively won by Theodore Weld and other abolitionists. Elisabeth attended most of the debates.:171 Her father and the trustees, afraid of more violence from anti-abolitionist whites, prohibited any further discussions of the topic.The result was a mass exodus of the Lane students, together with a supportive trustee and a professor, who moved as a group to the new Oberlin Collegiate Institute after its trustees agreed, by a close and acrimonious vote, to accept students regardless of “race”, and to allow discussions of any topic.It was in the literary club at Lane that she met Rev. Calvin Ellis Stowe, a widower who was a professor of Biblical Literature at the seminary. The two married at the Seminary on January 6, 1836. The Stowes had seven children together, including twin daughters.In 1850, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law, prohibiting assistance to fugitives and strengthening sanctions even in free states. At the time, Stowe had moved with her family to Brunswick, Maine, where her husband was now teaching at Bowdoin College. Their home near the campus is protected as a National Historic Landmark.The Stowes were ardent critics of slavery and supported the Underground Railroad, temporarily housing several fugitive slaves in their home. One fugitive from slavery, John Andrew Jackson, wrote of hiding with Stowe in her house in Brunswick, Maine, as he fled to Canada in his narrative titled “The Experience of a Slave in South Carolina” (London: Passmore & Albaster, 1862).Stowe claimed to have a vision of a dying slave during a communion service at Brunswick’s First Parish Church, which inspired her to write his story. However, what more likely allowed her to empathize with slaves was the loss of her eighteen-month-old son, Samuel Charles Stowe. She even stated the following, “Having experienced losing someone so close to me, I can sympathize with all the poor, powerless slaves at the unjust auctions.You will always be in my heart Samuel Charles Stowe.” On March 9, 1850, Stowe wrote to Gamaliel Bailey, editor of the weekly anti-slavery journal The National Era, that she planned to write a story about the problem of slavery: “I feel now that the time is come when even a woman or a child who can speak a word for freedom and humanity is bound to speak… I hope every woman who can write will not be silent.”Shortly after in June 1851, when she was 40, the first installment of Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in serial form in the newspaper The National Era. She originally used the subtitle “The Man That Was A Thing”, but it was soon changed to “Life Among the Lowly”. Installments were published weekly from June 5, 1851, to April 1, 1852. For the newspaper serialization of her novel, Stowe was paid $400. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in book form on March 20, 1852, by John P. Jewett with an initial print run of 5,000 copies.Each of its two volumes included three illustrations and a title-page designed by Hammatt Billings. In less than a year, the book sold an unprecedented 300,000 copies. By December, as sales began to wane, Jewett issued an inexpensive edition at 37½ cents each to stimulate sales. Sales abroad, as in Britain where the book was a great success, earned Stowe nothing as there was no international copyright agreement in place during that era.In late 1853 Stowe undertook a lecture tour of Britain and, to make up the royalties that she could not receive there, the Glasgow New Association for the Abolition of Slavery set up Uncle Tom’s Offering.According to Daniel R. Lincoln, the goal of the book was to educate Northerners on the realistic horrors of the things that were happening in the South. The other purpose was to try to make people in the South feel more empathetic towards the people they were forcing into slavery.The book’s emotional portrayal of the effects of slavery on individuals captured the nation’s attention. Stowe showed that slavery touched all of society, beyond the people directly involved as masters, traders and slaves. Her novel added to the debate about abolition and slavery, and aroused opposition in the South. In the South, Stowe was depicted as out of touch, arrogant, and guilty of slander.Within a year, 300 babies in Boston alone were named Eva (one of the book’s characters), and a play based on the book opened in New York in November. Southerners quickly responded with numerous works of what are now called anti-Tom novels, seeking to portray Southern society and slavery in more positive terms. Many of these were bestsellers, although none matched the popularity of Stowe’s work, which set publishing records.After the start of the Civil War, Stowe traveled to the capital, Washington, D.C., where she met President Abraham Lincoln on November 25, 1862. Stowe’s daughter, Hattie, reported, “It was a very droll time that we had at the White house I assure you… I will only say now that it was all very funny—and we were ready to explode with laughter all the while.”What Lincoln said is a minor mystery. Her son later reported that Lincoln greeted her by saying, “so you are the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war.” Her own accounts are vague, including the letter reporting the meeting to her husband: “I had a real funny interview with the President.”A year after the Civil War, Stowe purchased property near Jacksonville, Florida. In response to a newspaper article in 1873, she wrote, “I came to Florida the year after the war and held property in Duval County ever since. In all this time I have not received even an incivility from any native Floridian.”Stowe is controversial for her support of Elizabeth Campbell, Duchess of Argyll, whose father-in-law decades before was a leader in the Highland Clearances, the transformation of the remote Highlands of Scotland from a militia-based society to an agricultural one that supported far fewer people. The newly homeless moved to Canada, where very bitter accounts appeared.It was Stowe’s assignment to refute them using evidence the Duchess provided, in Letter XVII Volume 1 of her travel memoir Sunny Memories of Foreign Lands. Stowe was vulnerable when she seemed to defend the cruelties in Scotland as eagerly as she attacked the cruelties in the American South.In 1868, Stowe became one of the first editors of Hearth and Home magazine, one of several new publications appealing to women; she departed after a year. Stowe campaigned for the expansion of married women’s rights, arguing in 1869 that:[T]he position of a married woman … is, in many respects, precisely similar to that of the negro slave. She can make no contract and hold no property; whatever she inherits or earns becomes at that moment the property of her husband…. Though he acquired a fortune through her, or though she earned a fortune through her talents, he is the sole master of it, and she cannot draw a penny….[I]n the English common law a married woman is nothing at all. She passes out of legal existence.In the 1870s, Stowe’s brother Henry Ward Beecher was accused of adultery, and became the subject of a national scandal. Unable to bear the public attacks on her brother, Stowe again fled to Florida but asked family members to send her newspaper reports. Through the affair, she remained loyal to her brother and believed he was innocent.After her return to Connecticut, Mrs. Stowe was among the founders of the Hartford Art School, which later became part of the University of Hartford.The Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site is part of the restored Dawn Settlement at Dresden, Ontario, which is 20 miles east of Algonac, Michigan. The community for freed slaves founded by the Rev. Josiah Henson and other abolitionists in the 1830s has been restored. There’s also a museum. Henson and the Dawn Settlement provided Stowe with the inspiration for Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was one of three African Americans who served as a Republican Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana during the era of Reconstruction.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was one of three African Americans who served as a Republican Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana during the era of Reconstruction.In 1868, he became the first elected black lieutenant governor of a U.S. state. He ran on the ticket headed by Henry Clay Warmoth, formerly of Illinois. After he died in office, then-state Senator P. B. S. Pinchback, another black Republican, became lieutenant governor and thereafter governor for a 34-day interim period.Today in our History – June 13, 1868 – Oscar James Dunn (1826 – November 22, 1871) is elected Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana.He was born into slavery in 1826 in New Orleans. As his mother, Maria Dunn, was enslaved, he took her status under the law of the time. His father, James Dunn, had been freed in 1819 by his master. James was born into slavery in Petersburg, Virginia and had been transported to the Deep South in the forced migration of more than one million African Americans from the Upper South.He was bought by James H. Caldwell of New Orleans, who founded the St. Charles Theatre and New Orleans Gas Light Company. Dunn worked for Caldwell as a skilled carpenter for decades, including after his emancipation by Caldwell in 1819.After being emancipated, Dunn married Maria, then enslaved, and they had two children, Oscar and Jane. (Slave marriages were not recognized under the law.) By 1832, Dunn had earned enough money as a carpenter to purchase the freedom of his wife and both children.They gained the status of free Blacks decades before the American Civil War. As English speakers, they were not, however, part of the culture of free people of color, who were primarily of French descent, Catholic religion and culture.James Dunn continued to work as a carpenter for his former master Caldwell. His wife, Maria Dunn, ran a boarding house for actors and actresses who were in the city to perform at the Caldwell theatres. Together, they were able to pay for education for their children. Having studied music, Dunn became both an accomplished musician and an instructor of the violin.Oscar Dunn was apprenticed as a young man to a plastering and painting contractor, A. G. Wilson. (He had verified Dunn’s free status in the Mayor’s Register of Free People of Color 1840–1864.) On November 23, 1841, the contractor reported Dunn as a runaway in a newspaper ad in the New Orleans Times-Picayune. Dunn must have gone back to work because he progressed in the world.Dunn was an English-speaking free black in a city in which the racial caste system was the underpinning of daily life. Ethnic French, including many free people of color, believed their culture was more subtle and flexible than that brought by the English-speaking residents, who came to the city in the early-to-mid-19th century after the Louisiana Purchase and began to dominate it in number. Free people of color had been established as a separate class of merchants, artisans, and property owners, many of whom had educations. However, American migrants from the South dismissed their special status, classifying society in binary terms, as black or white, despite a long history of interracial relations in their own history.Dunn joined Prince Hall Richmond Lodge #4, one of a number of fraternal organizations that expanded to New Orleans, out of the Prince Hall Ohio Lodge during the 19th century. In the latter 1850s, he rose to Master and Grand Master of the Eureka Grand Lodge which became the Louisiana Grand Lodge [Prince Hall/York Rite]. Author and historian, Joseph A. Walkes, Jr., a Prince Hall Freemason, credits Dunn with outstanding conduct of Masonic affairs in Louisiana. As a Freemason, Dunn developed his leadership skills, and established a wide network and power base in the Black community that was essential for his later political career.In December 1866, Dunn married the widow Ellen Boyd Marchand, born free in Ohio, as the daughter of Henry Boyd and his wife of Ohio. He adopted her three children, Fannie (9), Charles (7) and Emma (5). The couple had no children together. In 1870, the Dunn family residence was located on Canal Street, one block west of South Claiborne Avenue and within walking distance of Straight University and the St. James A.M.E. Church complex, where they were members.Dunn began to work to achieve equality for the millions of blacks freed by passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, ratified after the American Civil War. He actively promoted and supported the Universal Suffrage Movement, advocated land ownership for all blacks, taxpayer-funded education of all black children, and equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment. He joined the Republican Party, many of whose members supported suffrage for blacks.Dunn opened an employment agency that assisted in finding jobs for the freedmen. He was appointed as Secretary of the Advisory Committee of the Freedmen’s Savings and Trust Company of New Orleans, established by the Freedmen’s Bureau. As the city and region struggled to convert to a free labor system, Dunn worked to ensure that recently freed slaves were treated fairly by former planters, who insisted on hiring by year-long contracts. In 1866, he organized the People’s Bakery, an enterprise owned and operated by the Louisiana Association of Workingmen.Elected to the New Orleans city council in 1867, Dunn was named chairman of a committee to review Article 5 of the City Charter. He proposed that “all children between the ages of 6–18 be eligible to attend public schools and that the Board of Aldermen shall provide for the education of all children … without distinction to color.”In the state Constitutional Convention of 1867–1868, the resolution was enacted into Louisiana law and laid the foundation for the public education system, established for the first time in the state by the biracial legislature.Dunn was very active in local, state and federal politics, with connections to U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant and U.S. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts. Long before President Theodore Roosevelt invited Booker T. Washington, President Ulysses S. Grant met him at the White House on April 2, 1869.Running for lieutenant governor, he beat a white candidate for the nomination, W. Jasper Blackburn, the former mayor of Minden in Webster Parish, by a vote of fifty-four to twenty-seven. The Warmoth-Dunn Republican ticket was elected, 64,941 to 38,046.That was considered the rise of the Radical Republican influence in state politics. Dunn was inaugurated lieutenant governor on June 13, 1868. He was also the President pro tempore of the Louisiana State Senate. He was a member of the Printing Committee of the legislature, which controlled a million-dollar budget. He also served as President of the Metropolitan Police with an annual budget of nearly one million dollars. It struggled to maintain peace in a volatile political atmosphere, especially after the New Orleans Riot of 1866. In 1870, Dunn served on the Board of Trustees and Examining Committee for Straight University, a historically black college founded in the city.The Republicans developed severe internal conflicts. Although elected with Warmoth, as the governor worked toward Fusionist goals, Dunn became allied with the Custom House faction, which was led by Stephen B. Packard and tied in with federal patronage jobs. They had differences with the Warmoth-Pinchback faction, and challenged it for leadership of the party. Warmoth had been criticized for appointing white Democrats to state positions, encouraging alliances with Democrats, and his failure to advance civil rights for blacks. William Pitt Kellogg, whom Warmoth had helped gain election as US Senator in 1868, also allied with Packard and was later elected as governor of the state.Because of Dunn’s wide connections and influence in the city, his defection to the Custom House faction meant that he would take many Republican ward clubs with him in switching allegiance, especially those made up of African Americans rather than Afro-Creoles (the mixed race elite that had been established as free before the war). For the Radical Republicans, the city was always more important to their political power than were the rural parishes.Dunn made numerous political enemies during this period. According to The New York Times, Dunn “had difficulties with Harry Lott”, a Rapides Parish member of the Louisiana House of Representatives (1868–1870, 1870–1872). He also had differences with his eventual successor as lieutenant governor, State Senator P.B.S. Pinchback over policy, leadership, and direction.On November 22, 1871, Dunn died at 45 at home after a brief and sudden illness. He had been campaigning for the upcoming state and presidential elections. There was speculation that he was poisoned by political enemies, but no evidence was found. According to Nick Weldon at the Historic New Orleans Collection, Dunn’s symptoms were consistent with arsenic poisoning—vomiting, shivering. Four out of seven doctors who examined Dunn refused to sign off on the official cause of death, suspecting murder. No confirmation was made because Dunn’s family had refused an autopsy.The Dunn funeral was reported as one of the largest in New Orleans. As many as 50,000 people lined Canal Street for the procession, and newspapers across the nation reported the event. State officials, Masonic lodges, and civic and social organizations participated in the procession from the St. James A.M.E. church to his grave site. He was interred in the Cassanave family mausoleum at St. Louis Cemetery No. 2. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!