GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event was The Tulsa race massacre (known alternatively as the Tulsa race riot, the Greenwood Massacre, the Black Wall Street Massacre, the Tulsa pogrom, or the Tulsa Massacre) took place on May 31 and June 1, 1921, when mobs of white residents, many of them deputized and given weapons by city officials, attacked black residents and businesses of the Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It has been called “the single worst incident of racial violence in American history.” The attack, carried out on the ground and from private aircraft, destroyed more than 35 square blocks of the district—at that time the wealthiest black community in the United States, known as “Black Wall Street.”More than 800 people were admitted to hospitals, and as many as 6,000 black residents were interned in large facilities, many of them for several days. The Oklahoma Bureau of Vital Statistics officially recorded 36 dead. A 2001 state commission examination of events was able to confirm 39 dead, 26 black and 13 white, based on contemporary autopsy reports, death certificates and other records. The commission gave several estimates ranging from 75 to 300 dead.The massacre began during the Memorial Day weekend after 19-year-old Dick Rowland, a black shoeshiner, was accused of assaulting Sarah Page, the 17-year-old white elevator operator of the nearby Drexel Building. He was taken into custody. After the arrest, rumors spread through the city that Rowland was to be lynched. Upon hearing reports that a mob of hundreds of white men had gathered around the jail where Rowland was being kept, a group of 75 black men, some of whom were armed, arrived at the jail to ensure that Rowland would not be lynched. The sheriff persuaded the group to leave the jail, assuring them that he had the situation under control. As the group was leaving the premises, complying with the sheriff’s request, a member of the mob of white men allegedly attempted to disarm one of the black men. A shot was fired, and then according to the reports of the sheriff, “all hell broke loose.” At the end of the firefight, 12 people were killed: 10 white and 2 black. As news of these deaths spread throughout the city, mob violence exploded. White rioters rampaged through the black neighborhood that night and morning killing men and burning and looting stores and homes. Around noon on June 1, the Oklahoma National Guard imposed martial law, effectively ending the massacre.About 10,000 black people were left homeless, and property damage amounted to more than $1.5 million in real estate and $750,000 in personal property (equivalent to $32.25 million in 2019). Many survivors left Tulsa, while black and white residents who stayed in the city kept silent about the terror, violence, and resulting losses for decades. The massacre was largely omitted from local, state, and national histories.In 1996, 75 years after the massacre, a bipartisan group in the state legislature authorized formation of the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. The commission’s final report, published in 2001, states that the city had conspired with the mob of white citizens against black citizens; it recommended a program of reparations to survivors and their descendants. The state passed legislation to establish scholarships for descendants of survivors, encourage economic development of Greenwood, and develop a memorial park to the massacre victims in Tulsa. The park was dedicated in 2010. In 2020, the massacre became a part of the Oklahoma school curriculum. The last male survivor of the Tulsa race massacre, R&B and jazz saxophonist Hal Singer, died on August 18, 2020, at age 100.Today in our History May 31, 1921 – The Tulsa, OK race riots.On May 30, 1921, Dick Rowland, a young African American shoe shiner, was accused of assaulting a white elevator operator named Sarah Page in the elevator of a building in downtown Tulsa. The next day, the Tulsa Tribune printed a story saying that Rowland had tried to rape Page, with an accompanying editorial stating that a lynching was planned for that night. That evening mobs of both African Americans and whites descended on the courthouse where Rowland was being held. When a confrontation between an armed African American man, there to protect Rowland, and a white protestor resulted in the death of the latter, the white mob was incensed, and the Tulsa massacre was thus ignited.Over the next two days, mobs of white people looted and set fire to African American businesses and homes throughout the city. Many of the mob members were recently returned World War I veterans trained in the use of firearms and are said to have shot African Americans on sight. Some survivors even claimed that people in airplanes dropped incendiary bombs.When the massacre ended on June 1, the official death toll was recorded at 10 whites and 26 African Americans, though many experts now believe at least 300 people were killed. Shortly after the massacre there was a brief official inquiry, but documents related to the massacre disappeared soon afterward. The event never received widespread attention and was long noticeably absent from the history books used to teach Oklahoma schoolchildren.In 1997 a Tulsa Race Riot Commission was formed by the state of Oklahoma to investigate the massacre and formally document the incident. Members of the commission gathered accounts of survivors who were still alive, documents from individuals who witnessed the massacre but had since died, and other historical evidence. Scholars used the accounts of witnesses and ground-piercing radar to locate a potential mass grave just outside Tulsa’s Oaklawn Cemetery, suggesting the death toll may be much higher than the original records indicate. In its preliminary recommendations, the commission suggested that the state of Oklahoma pay $33 million in restitution, some of it to the 121 surviving victims who had been located. However, no legislative action was ever taken on the recommendation, and the commission had no power to force legislation. In April 2002 a private religious charity, the Tulsa Metropolitan Ministry, paid a total of $28,000 to the survivors, a little more than $200 each, using funds raised from private donations. Research more about this great American Tragedy and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

Month: May 2021

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was one of three Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) field/social workers killed in Philadelphia, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux Klan.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was one of three Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) field/social workers killed in Philadelphia, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux Klan. The others were Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner from New York City.Today in our History – May 30, 1943 – James Earl Chaney (May 30, 1943 – June 21, 1964) was born.James Chaney was born the eldest son of Fannie Lee and Ben Chaney, Sr. His brother Ben was nine years younger, born in 1952. He also had three sisters, Barbara, Janice, and Julia. His parents separated for a time when James was young. James attended Catholic school for the first nine grades, and was a member of St Joseph Catholic Church. At the age of 15 as a high school student, he and some of his classmates began wearing paper badges reading “NAACP”, to mark their support for the national civil rights organization, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, founded in 1910. They were suspended for a week from the segregated high school, because the principal feared the reaction of the all-white school board. After high school, Chaney started as a plasterer’s apprentice in a trade union. In 1962, Chaney participated in a Freedom Ride from Tennessee to Greenville, Mississippi, and in another from Greenville to Meridian. He and his younger brother participated in other non-violent demonstrations, as well. James Chaney started volunteering in late 1963, and joined the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in Meridian. He organized voter education classes, introduced CORE workers to local church leaders, and helped CORE workers get around the counties.In 1964, he met with leaders of the Mt. Nebo Baptist Church to gain their support for letting Michael Schwerner, CORE’s local leader, come to address the church members, to encourage them to use the church for voter education and registration. Chaney also acted as a liaison with other CORE members. In June 1964, Chaney and fellow civil rights workers Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman were killed near the town of Philadelphia, Mississippi.They were investigating the burning of Mt. Zion Methodist Church, which had been a site for a CORE Freedom School. In the wake of Schwerner and Chaney’s voter registration rallies, parishioners had been beaten by whites. They accused the sheriff’s deputy, Cecil Price, of stopping their caravan and forcing the deacons to kneel in the headlights of their own cars, while white men beat them with rifle butts. The same whites who beat them were also identified as having burned the church.Price arrested Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner for an alleged traffic violation and took them to the Neshoba County jail. They were released that evening, without being allowed to telephone anyone. On the way back to Meridian, they were stopped by patrol lights and two carloads of Ku Kux Klan members on Highway 19, then taken in Price’s car to another remote rural road. The men approached then shot and killed Schwerner, then Goodman, both with one shot in the heart and finally Chaney with three shots, after severely beating him. They buried the young men in an earthen dam nearby.The men’s bodies remained undiscovered for 44 days. The FBI was brought into the case by John Doar, the Department of Justice representative in Mississippi monitoring the situation during Freedom Summer. The missing civil rights workers became a major national story, especially coming on top of other events as civil rights workers were active across Mississippi in a voter registration drive.Schwerner’s widow Rita, who also worked for CORE in Meridian, expressed indignation that the press had ignored previous murders and disappearances of blacks in the area, but had highlighted this case because two white men from New York had gone missing. She said she believed that if only Chaney were missing, the case would not have received nearly as much attention. After the funeral of their older son, the Chaneys left Mississippi because of death threats. Helped by the Goodman and Schwerner families, and other supporters, they moved to New York City, where Chaney’s younger brother Ben attended a private, majority-white high school.In 1969, Ben joined the Black Panther Party and Black Liberation Army. In 1970, he went to Florida with two friends to buy guns; the two friends killed three white men in South Carolina and Florida, and Chaney was also convicted of murder in Florida. Chaney served 13 years and, after gaining parole, founded the James Earl Chaney Foundation in his brother’s honor. Since 1985, he has worked “as a legal clerk for the former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark, the lawyer who secured his parole”.In 1967, the US government went to trial, charging ten men with conspiracy to deprive the three murdered men of their civil rights under the Enforcement Act of 1870, the only federal law then applying to the case. The jury convicted seven men, including Deputy Sheriff Price, and three were acquitted, including Edgar Ray Killen, the former Ku Klux Klan organizer who had planned and directed the murders.Over the years, activists had called for the state to prosecute the murderers. The journalist Jerry Mitchell, an award-winning investigative reporter for the Jackson Clarion-Ledger, had discovered new evidence and written extensively about the case for six years. Mitchell had earned renown for helping secure convictions in several other high-profile Civil Rights Era murder cases, including the assassination of Medgar Evers, the Birmingham church bombing, and the murder of Vernon Dahmer. He developed new evidence about the civil rights murders, found new witnesses, and pressured the State to prosecute. It began an investigation in the early years of the 2000s.In 2004, Barry Bradford, an Illinois high school teacher, and his three students, Allison Nichols, Sarah Siegel, and Brittany Saltiel, joined Mitchell’s efforts in a special project. They conducted additional research and created a documentary about their work. Their documentary, produced for the National History Day contest, presented important new evidence and compelling reasons for reopening the case. They obtained a taped interview with Edgar Ray Killen, who had been acquitted in the first trial. He had been an outspoken white supremacist nicknamed the “Preacher”. The interview helped convince the State to reopen an investigation into the murders.In 2005, the state charged Killen in the murders of the three activists; he was the only one of six living suspects to be charged.When the trial opened on January 7, 2005, Killen pleaded “Not guilty”. Evidence was presented that he had supervised the murders. Not sure that Killen intended in advance for the activists to be killed by the Klan, the jury found him guilty of three counts of manslaughter on June 20, 2005, and he was sentenced to 60 years in prison—20 years for each count, to be served consecutively.Believing there are other men involved in his brother’s death who should be charged as accomplices to murder, as Killen was, Ben Chaney has said: “I’m not as sad as I was. But I’m still angry”.In 1998, Ben Chaney established the James Earl Chaney Foundation in his older brother’s honor, to promote the work of civil rights and social justice. Chaney, along with Goodman and Schwerner, received a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama in 2014. Research more about this tragic event and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’ American Champion was an American abolitionist and women’s rights activist

GM – FBF – Today’ American Champion was an American abolitionist and women’s rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to freedom in 1826. After going to court to recover her son in 1828, she became the first black woman to win such a case against a white man.She gave herself the name Sojourner Truth in 1843 after she became convinced that God had called her to leave the city and go into the countryside “testifying the hope that was in her”. Her best-known speech was delivered extemporaneously, in 1851, at the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. The speech became widely known during the Civil War by the title “Ain’t I a Woman?”, a variation of the original speech re-written by someone else using a stereotypical Southern dialect, whereas Sojourner Truth was from New York and grew up speaking Dutch as her first language. During the Civil War, Truth helped recruit black troops for the Union Army; after the war, she tried unsuccessfully to secure land grants from the federal government for formerly enslaved people (summarized as the promise of “forty acres and a mule”).A memorial bust of Truth was unveiled in 2009 in Emancipation Hall in the U.S. Capitol Visitor’s Center. She is the first African American woman to have a statue in the Capitol building. In 2014, Truth was included in Smithsonian magazine’s list of the “100 Most Significant Americans of All Time”.Today in our History – May 29, 1854 – Sojourner Truth delivers her famous “Ain’t I a Woman” speech at the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, OH.Isabella was the daughter of slaves and spent her childhood as an abused chattel of several masters. Her first language was Dutch. Between 1810 and 1827 she bore at least five children to a fellow slave named Thomas. Just before New York state abolished slavery in 1827, she found refuge with Isaac Van Wagener, who set her free. With the help of Quaker friends, she waged a court battle in which she recovered her small son, who had been sold illegally into slavery in the South. About 1829 she went to New York City with her two youngest children, supporting herself through domestic employment.Since childhood Isabella had had visions and heard voices, which she attributed to God. In New York City she became associated with Elijah Pierson, a zealous missionary. Working and preaching in the streets, she joined his Retrenchment Society and eventually his household.In 1843 she left New York City and took the name Sojourner Truth, which she used from then on. Obeying a supernatural call to “travel up and down the land,” she sang, preached, and debated at camp meetings, in churches, and on village streets, exhorting her listeners to accept the biblical message of God’s goodness and the brotherhood of man. In the same year, she was introduced to abolitionism at a utopian community in Northampton, Massachusetts, and thereafter spoke in behalf of the movement throughout the state. In 1850 she traveled throughout the Midwest, where her reputation for personal magnetism preceded her and drew heavy crowds. She supported herself by selling copies of her book, The Narrative of Sojourner Truth, which she had dictated to Olive Gilbert.Encountering the women’s rights movement in the early 1850s, and encouraged by other women leaders, notably Lucretia Mott, she continued to appear before suffrage gatherings for the rest of her life.In the 1850s Sojourner Truth settled in Battle Creek, Michigan. At the beginning of the American Civil War, she gathered supplies for black volunteer regiments and in 1864 went to Washington, D.C., where she helped integrate streetcars and was received at the White House by President Abraham Lincoln. The same year, she accepted an appointment with the National Freedmen’s Relief Association counseling former slaves, particularly in matters of resettlement. As late as the 1870s she encouraged the migration of freedmen to Kansas and Missouri. In 1875 she retired to her home in Battle Creek, where she remained until her death. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies and make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is a strong force in America.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is a strong force in America. I have been in her company with Les Brown who she was married to in NYC for a taping of his T.V. show that my students from Red Bank Regional took part in. Also in Atlanta, my Mother and two Aunts while visiting my family back in the early 2000’s met her again at one of her restaurants and they were so happy to be in her company. Today’s American Champion is an American singer, songwriter, actress, businesswoman, and author. A seven-time Grammy Award-winner, Knight is known for the hits she recorded during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s with her group Gladys Knight & the Pips, which also included her brother Merald “Bubba” Knight and cousins William Guest and Edward Patten.Knight has recorded two number-one Billboard Hot 100 singles (“Midnight Train to Georgia” and “That’s What Friends Are For”), eleven number-one R&B singles, and six number-one R&B albums.She has won seven Grammy Awards (four as a solo artist and three with the Pips) and is an inductee into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Vocal Group Hall of Fame along with The Pips. Two of her songs (“I Heard It Through the Grapevine” and “Midnight Train to Georgia”) were inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame for “historical, artistic and significant” value. She also recorded the theme song for the 1989 James Bond film Licence to Kill. Rolling Stone magazine ranked Knight among the 100 Greatest Singers of All Time.Today in our History – May 28, 1944 – Gladys Maria Knight (born May 28, 1944) was born.Singer Gladys Knight has given voice to multiple R&B hits (with and without her Pips), including “Midnight Train to Georgia.”Gladys Knight began singing with her siblings at age 8, calling themselves “the Pips.” The group opened for R&B legends in the 1950s, then headed to Motown and crossed over to pop music. As Gladys Knight and the Pips, they recorded their signature song, “Midnight Train to Georgia.” Knight left the Pips behind in 1989, and continued to perform and record as a solo artist. Today, she’s known fondly as the “Empress of Soul.”Singer and actress Gladys Knight was born Gladys Maria Knight on May 28, 1944, in Atlanta, Georgia, and started out on the road to success at an early age. She made her solo debut at the age of 4, singing at the Mount Mariah Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia. Not long after, she won a prize for her performance on the televised Ted Mack Amateur Hour.In 1952, an 8-year-old Knight formed “the Pips” with her brother and sister, Merald (“Bubba”) and Brenda, and two cousins, Elenor and William Guest (another cousin, Edward Patten, and Langston George later joined the group, after Brenda and Elenor left to get married; George left by 1960). With young Gladys supplying the throaty vocals and the Pips providing impressive harmonies and inspired dance routines, the group soon earned a following on the so-called “Chitlin Circuit” in the South, opening for popular acts such as Jackie Wilson and Sam Cooke.While their first single, “Whistle My Love,” was released by Brunswick in 1957, the Pips didn’t score a bona fide hit until 1961 when they released “Every Beat of My Heart.” But it was when the group began recording with Motown Records in the mid-1960s, and were teamed with songwriter/producer Norman Whitfield, that their careers really took off. In 1967, the Pips’ version of Whitfield’s “I Heard it Through the Grapevine”—later a huge hit for Marvin Gaye—crossed over from the rhythm and blues charts to the pop charts. Their popularity increased with the success of singles like “Nitty Gritty,” “Friendship Train” and “If I Were Your Woman,” combined with touring performances with the Motown Revue and numerous TV appearances.Knight and the Pips left Motown in 1973 for Buddah Records, a subsidiary of Arista (the group later took Motown to court for unpaid royalties). Ironically, their last Motown single, “Neither One of Us Wants to be the First to Say Goodbye,” became the Pips’ first No. 1 crossover hit and a Grammy winner for Best Pop Vocal Performance in 1973.The group — now known officially as Gladys Knight and the Pips — was riding higher than ever during the mid-1970s with a smoother, more accessible sound, a hit album, Imagination (1973) and three gold singles: “I’ve Got to Use My Imagination,” “Best Thing That Ever Happened to Me” and the Grammy Award-winning No. 1 hit “Midnight Train to Georgia” (Best R&B Vocal Performance). In 1974, the group recorded the soundtrack for the film Claudine, with songs written by Curtis Mayfield; the soundtrack album spawned the hit single “On and On.” Their next album, I Feel a Song (1975), included Knight’s hit version of Marvin Hamlisch’s “The Way We Were,” also popularized by Barbra Streisand; the album’s title track became a No. 1 soul hit.Knight and the Pips hosted their own TV special in the summer of 1975, and in 1976, Knight made an appearance in the film Pipe Dreams, for which she and the Pips also recorded the soundtrack album. She later co-starred opposite comedian Flip Wilson on the 1985-86 sitcom Charlie & Co. Due to legal problems with Buddah, Knight and the Pips were forced to record separately in the last years of the 1970s, although they continued performing together in live gigs. After signing a new contract with Columbia, the group released three reunion albums during the early 1980s, About Love (1980), Touch (1982) and Visions (1983), scoring hits with such singles as “Landlord” (produced by the ace songwriting team Ashford and Simpson), “Save the Overtime for Me” and “You’re Number One”012Moving to MCA Records in 1988, Knight and the Pips released their final album together, All Our Love, which included the Grammy-winning single “Love Overboard.” The next year, Knight left the Pips to launch a solo career, recording the title song for the James Bond film Licence to Kill (1989) and the album A Good Woman (1990), which featured guest stars Dionne Warwick and Patti Labelle.Throughout the 1990s, Knight continued to tour and record, producing the successful 1994 album Just For You and earning acclaim for her consistently strong vocals and hardworking performance style. In addition to her musical career, she also acted in a recurring role on the 1994 TV series New York Undercover. Knight has also appeared on Living Single and JAG. On the big screen, she had a role in Tyler Perry’s I Can Do Bad All By Myself in 2009.While no longer a chart-topping success, Knight, known fondly today as the “Empress of Soul,” has continued to make records. She once stated, “Since I’ve been so wonderfully blessed, I really want to share and to make life at least a little better. So every chance I get to share the gospel or uplift people, I will take full advantage of that opportunity.” Knight collaborated with the the Saints United Voices for her 2005 gospel album One Voice, which did well. Knight’s 2006 album Before Me also received a warm reception.In 2012, Knight decided to take on another kind of role by joining the cast of Dancing with the Stars, the popular television competition, and strutting her stuff against the likes of actress Melissa Gilbert, actor Jaleel White and TV personality Sherri Shepherd. Two years later, she released another studio album, the gospel-infused Where My Heart Belongs.In early 2019, it was announced that Knight would sing the national anthem before Super Bowl LIII.Knight married her first husband, an Atlanta musician named Jimmy Newman, at age 16. The marriage produced two children, James and Kenya, before Newman, a drug addict, abandoned the family and died only a few years later. Her second marriage, to Barry Hankerson, ended acrimoniously in 1979 after five years in a prolonged custody battle over their son, Shanga. Knight married author and motivational speaker Les Brown in 1995; that marriage ended in 1997.In addition to a tumultuous love life, Knight suffered through a serious gambling problem that lasted more than a decade. In the late 1980s, after losing $45,000 in one night at the baccarat table, Knight joined Gamblers Anonymous, which helped her quit the habit.Since 1978, Knight has lived in Las Vegas, close to her mother, Elizabeth, and two of her children and their families. She continues to perform frequently in Las Vegas and beyond, and published a memoir, Between Each Line of Pain and Glory: My Life Story, in 1997. With the Pips, she was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996 and received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Rhythm & Blues Foundation in 1998.In April 2001, Knight married William McDowell, a corporate consultant she had reportedly met 10 years earlier, but had only begun dating the previous January.Research more about this great American Champion and shar it with your babies,

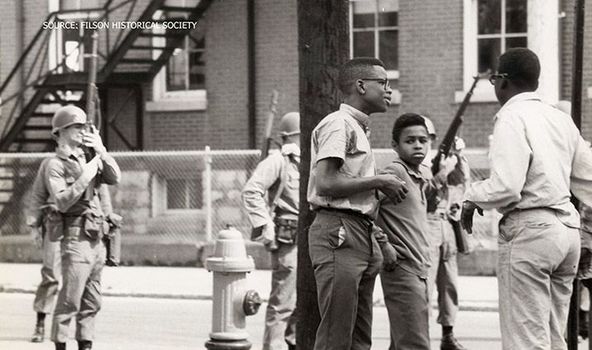

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion moment was at the beginning of the summer in 1968; keep in mind Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated a month before and tensions in urban centers were still high and at the tipping point in many.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion moment was at the beginning of the summer in 1968; keep in mind Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated a month before and tensions in urban centers were still high and at the tipping point in many.Trenton, New Jersey my hometown was hit hard from that April throw-out the summer. In a town where the “Greatest” Muhammad Ali was from it exploded but they were sparked in the aftermath of a police brutality case as well as racial tensions. As I continue my focus on “Red Summer” -1919 remembrance. Never Again!Remember – “You know, as a child when I was growing up, that was the epicenter of where I lived,” – Louisville Metro Council President DavidToday in our History – May 27, 1968 – 51 Years Later: Remembering Louisville’s 1968 riots.By 11:00 AM (CST) a rally was taken place at 28th and Greenwood, in the Parkland neighborhood to protest an arrest that had happened a few weeks’ prior on May 8, 1968.The intersection and Parkland in general, had recently become an important location for Louisville’s black community, as the local NAACP branch had moved its office there.The men arrested were Charles Thomas and a real estate broker by the name of Manfred G. Reid. Reid questioned officers about Thomas’s arrest which caused a crowd of about 200 African Americans to gather and begin to yell at the officers as the two were taken into custody.Three weeks later, a rally which consisted of close to 350-400 people was devised as a plan to discuss the arrest of Thomas and Reid. At the rally, there were several speakers who gave their opinions on the arrest of the two gentleman.The crowd was protesting against the possible reinstatement of a white officer who had been suspended for beating a black man some weeks earlier.Several community leaders arrived and told the crowd that no decision had been reached, and alluded to disturbances in the future if the officer was reinstated. By 8:30, the crowd began to disperse.However, rumors (which turned out to be untrue) were spread that Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee speaker Stokely Carmichael’s plane to Louisville was being intentionally delayed by whites. After bottles were thrown by the crowd, the crowd became unruly and police were called.However, the small and unprepared police response simply upset the crowd more, which continued to grow. The police, including a captain who was hit in the face by a bottle, retreated, leaving behind a patrol car, which was turned over and burned.By midnight, rioters had looted stores as far east as Fourth Street, overturned cars and started fires.Within an hour, Mayor Kenneth A. Schmied requested 700 Kentucky National Guard troops and established a citywide curfew. Violence and vandalism continued to rage the next day, but had subdued somewhat by May 29.Business owners began to return, although troops remained until June 4. Police made 472 arrests related to the riots. Two black teenage rioters had died, and $200,000 in damage had been done.The disturbances had a longer-lasting effect. Most white business owners quickly pulled out or were forced, by the threat of racial violence, out of Parkland and surrounding areas.Most white residents also left the West End, which had been almost entirely white north of Broadway, from subdivision until the 1960s. The riot would have effects that shaped the image which whites would hold of Louisville’s West End, that it was predominantly black.In the 51 years since the riots of 1968, much has changed in Louisville’s West End. Many businesses have long left the area near 28th and Greenwood. Research more about race riots in America and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – LIF – Today’s American Champion was an American tennis player and professional golfer, and one of the first Black athletes to cross the color line of international tennis.

GM – LIF – Today’s American Champion was an American tennis player and professional golfer, and one of the first Black athletes to cross the color line of international tennis. In 1956, she became the first African American to win a Grand Slam title (the French Championships).The following year she won both Wimbledon and the US Nationals (precursor of the US Open), then won both again in 1958 and was voted Female Athlete of the Year by the Associated Press in both years. In all, she won 11 Grand Slam tournaments: five singles titles, five doubles titles, and one mixed doubles title.Gibson was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame and the International Women’s Sports Hall of Fame. “She is one of the greatest players who ever lived”, said Bob Ryland, a tennis contemporary and former coach of Venus and Serena Williams. “Martina [Navratilova] couldn’t touch her. I think she’d beat the Williams sisters.” In the early 1960s she also became the first Black player to compete on the Women’s Professional Golf Tour.At a time when racism and prejudice were widespread in sports and in society, Gibson was often compared to Jackie Robinson. “Her road to success was a challenging one”, said Billie Jean King, “but I never saw her back down.” “To anyone, she was an inspiration, because of what she was able to do at a time when it was enormously difficult to play tennis at all if you were Black”, said former New York City Mayor David Dinkins. “I am honored to have followed in such great footsteps”, wrote Venus Williams. “Her accomplishments set the stage for my success, and through players like myself and Serena and many others to come, her legacy will live on. Today in our History – May 26, 1956 – Althea Neale Gibson (August 25, 1927 – September 28, 2003) wins the French Open championship, becoming the first African-American woman to win a major tennis championship.Althea Gibson was the first African American tennis player to compete at the U.S. National Championships in 1950, and the first Black player to compete at Wimbledon in 1951. Althea Gibson developed a love of tennis at an early age, but in the 1940s and ’50s, most tournaments were closed to African Americans. Gibson kept playing (and winning) until her skills could no longer be denied, and in 1951, she became the first African American to play at Wimbledon. Gibson won the women’s singles and doubles at Wimbledon in 1957 and won the U.S. Open in 1958. Althea Neale Gibson was born on August 25, 1927, in Silver, South Carolina. Gibson blazed a new trail in the sport of tennis, winning some of the sport’s biggest titles in the 1950s, and broke racial barriers in professional golf as well.At a young age, Gibson moved with her family to Harlem, a neighborhood in the borough of New York City. Gibson’s life at this time had its hardships. Her family struggled to make ends meet, living on public assistance for a time, and Gibson struggled in the classroom, often skipping school altogether.However, Gibson loved to play sports — especially table tennis — and she soon made a name for herself as a local table tennis champion. Her skills were eventually noticed by musician Buddy Walker, who invited her to play tennis on local courts.After winning several tournaments hosted by the local recreation department, Gibson was introduced to the Harlem River Tennis Courts in 1941. Incredibly, just a year after picking up a racket for the first time, she won a local tournament sponsored by the American Tennis Association, an African American organization established to promote and sponsor tournaments for Black players. She picked up two more ATA titles in 1944 and 1945.Then, after losing one title in 1946, Gibson won 10 straight championships from 1947 to 1956. Amidst this winning streak, she made history as the first African American tennis player to compete at both the U.S. National Championships (1950) and Wimbledon (1951).Gibson’s success at those ATA tournaments paved the way for her to attend Florida A&M University on a sports scholarship. She graduated from the school in 1953, but it was a struggle for her to get by.At one point, she even thought of leaving sports altogether to join the U.S. Army. A good deal of her frustration had to do with the fact that so much of the tennis world was closed off to her. The white-dominated, white-managed sport was segregated in the United States, as was the world around it.The breaking point came in 1950, when Alice Marble, a former tennis No. 1 herself, wrote a piece in American Lawn Tennis magazine lambasting her sport for denying a player of Gibson’s caliber to compete in the world’s best tournaments. Marble’s article caught notice, and by 1952 — just one year after becoming the first Black player to compete at Wimbledon — Gibson was a Top 10 player in the United States. She went on to climb even higher, to No. 7 by 1953.In 1955, Gibson and her game were sponsored by the United States Lawn Tennis Association, which sent her around the world on a State Department tour that saw her compete in places like India, Pakistan and Burma. Measuring 5 feet, 11 inches, and possessing superb power and athletic skill, Gibson seemed destined for bigger victories. In 1956, it all came together when she won the French Open. Wimbledon and U.S. Open titles followed in both 1957 and 1958. (She won both the women’s singles and doubles at Wimbledon in 1957, which was celebrated by a ticker-tape parade when she returned home to New York City.) In all, Gibson powered her way to 56 singles and doubles championships before turning pro in 1959.1926)For her part, however, Gibson downplayed her pioneering role. “I have never regarded myself as a crusader,” she states in her 1958 autobiography, I Always Wanted to Be Somebody. “I don’t consciously beat the drums for any cause, not even the negro in the United States.”Althea Gibson kisses the cup she was rewarded with after having won the French International Tennis Championships in Paris.As a professional, Gibson continued to win — she landed the singles title in 1960 — but just as importantly, she started to make money. She was reportedly paid $100,000 for playing a series of matches before Harlem Globetrotter games. For a short time, too, the athletically gifted Gibson turned to golf, making history again as the first Black woman ever to compete on the pro tour.But failing to win on the course as she had on the courts, she eventually returned to tennis. In 1968, with the advent of tennis’ Open era, Gibson tried to repeat her past success. She was too old and too slow-footed, however, to keep up with her younger counterparts.Following her retirement, in 1971, Gibson was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame. She stayed connected to sports, however, through a number of service positions. Beginning in 1975, she served 10 years as commissioner of athletics for New Jersey State. She was also a member of the governor’s council on physical fitness.But just as her early childhood had been, Gibson’s last few years were dominated by hardship. She nearly went bankrupt before former tennis great Billie Jean King and others stepped in to help her out. Her health, too, went into decline.She suffered a stroke and developed serious heart problems. On September 28, 2003, Gibson died of respiratory failure in East Orange, New Jersey. Research more about this great American Champion and share iy with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American former professional basketball player and coach best known for his longtime association with the Golden State Warriors.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American former professional basketball player and coach best known for his longtime association with the Golden State Warriors. Nicknamed the “Destroyer”,[1][2] he played the point guard position and spent his entire 11 seasons (1960–1971) in the National Basketball Association (NBA) with the team.Today in our History – May 25, 1975 – Alvin Austin Attles Jr. (born November 7, 1936) FIRST AFRICAN-AMERICAN COACH TO WIN A PROFESSIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP IN ANY TEAM SPORTAl Attles earned the nickname “The Destroyer” during his days playing for the Philadelphia, and later relocated, San Francisco Warriors. He was an enforcer, albeit an unusual one, standing only six feet tall, a full head shorter than the big forwards and even bigger centers that Attles so coolly sparred with on occasion. Attles was drafted in the fifth round by the Warriors in the 1960 NBA Draft, the same year Oscar Robertson, Jerry West, and Lenny Wilkens entered the league. Over the next six decades, Attles managed to work for his beloved Warriors as a player, player-coach, head coach, general manager, vice-president, and consultant. His greatest triumph came in 1975 when Attles coached the underdog Warriors to a four-game sweep of the Washington Bullets in the NBA Finals. Attles won 557 games as the head man in Oakland, his coaching style proving more low-key than his disposition as a player. In 14 seasons, the Warriors reached the playoffs six times.As a general manager, Attles helped bring talent to the Bay Area including Chris Mullin, Robert Parish, and coach George Karl. The Destroyer was a cornerstone in the Warriors long history, enjoying one of the longest associations with a single franchise ever.Al Attles was not born to brawl. No need to. The diesel-truck rumble of his voice and his ability to summon a petrifying glare are weapons that enable him to issue warnings without needing a fist. Understand, Attles will not dodge a battle, but he must be threatened to fully engage. The former Warriors player, coach and executive, fights only in case of emergency. Once activated, he has no quit. Emergency confronted Attles a couple years ago, not long after he turned 80. One surgery led to another, then another. And, finally, a fourth. The threat was real.“He had multiple surgeries and his doctors told us all along that when someone is in their 80s, multiple surgeries take a toll,” Alvin Attles III said Tuesday night, hours after the Warriors unveiled practice courts at Chase Center bearing his name: Alvin Attles Courts.During his 60 years of employment with the franchise, from Philadelphia to San Francisco to Oakland and, now, back to San Francisco, Attles has been the embodiment of dignity with the humility of an earthly servant. His number was retired in 1977 and raised to the rafters. And now his name is inscribed in a place where it can be seen every day by every player taking the court. He has, at the very least, earned that much.The best sight of the day was Attles himself, shaking hands, slapping backs and cracking wise.“I’ve been very fortunate,” he said a few hours later, over the phone. “If somebody had told me when I was in college that things would turn out the way they have, I would have told them they had to be joking. It’s been a nice trip. I have nothing to complain about.”Less than three weeks after being inducted in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, the 82-year-old was strolling about Chase Center asking folks for money just to grant himself the joy of observing their puzzled reactions.Attles said a few words — mostly self-deprecating — of appreciation to a group of 60 or 70 Warriors employees that had gathered for the occasion. His presence was inspirational, in general, but particularly so given his two-year journey.“He wasn’t eating, and now we can’t stop him from eating,” Attles III said. “He wasn’t talking, and now we can’t stop him from talking. He’s walking and he has regained his range of motion.“But he came back from a very grave place.”There were moments when Attles’ family was deeply concerned about his recovery, even as they knew he would not surrender, no matter the darkness of the day.Attles’ fight consumed so much of his energy that his reserved seat at the top of the lower bowl of Oracle Arena was empty for long stretches. He was in and of hospitals and rehab centers. There was an aura of mystery as his family maintained, as he wished a measure of privacy.Attles lost about 40 percent of his body weight. Attacking his rehab with the ferocity he once exhibited as a player and coach, and regaining his appetite, he has over the past few months regained most of those pounds. When he arrived at the team’s Oakland facility in June to present an award to Steph Curry, Attles had use of a cane and often leaned on his son.No cane on Tuesday. Not much leaning, either. Attles the younger was free to mingle and watch from a distance as his dad owned the floor bearing his name.Attles was the coach of the 1974-75 Warriors, who won the first championship after the franchise relocated to the Bay Area from Philly in 1962.His 557 wins are the most by any Warriors coach (Steve Kerr is third, with 322; Don Nelson is second with 422). After 13 seasons on the bench, Attles spent three more years as the team’s general manager.For the last 30 years, throughout the highs and lows of the franchise, he has been the most revered man in the building simply by being worthy of reverence. The legend lives by never compromising his credibility.“You have to be honest with what you do, and what you don’t do,” he said. “The reason for that is if you do something and don’t live up to it, nobody wants to deal with you. It’s the same if you don’t do something after you said you would. But if people know you’re telling them the truth, they’ll always deal with you.” Research more about this great American Champion and share them with your babies Make it a champion day!

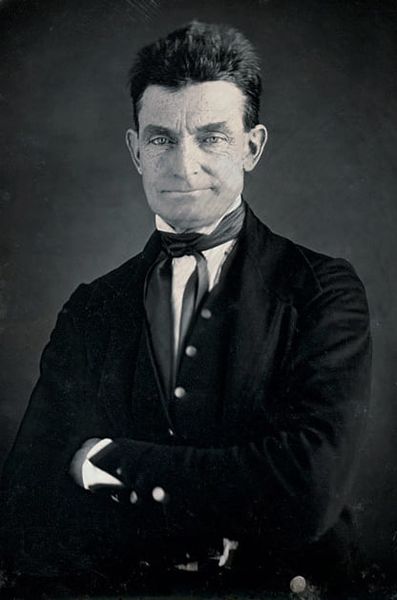

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event took place on the night of May 24, 1856, the radical abolitionist and five of his sons, and three other associates murdered five proslavery men at three different cabins along the banks of Pottawatomie Creek, near present-day Lane, Kansas.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event took place on the night of May 24, 1856, the radical abolitionist and five of his sons, and three other associates murdered five proslavery men at three different cabins along the banks of Pottawatomie Creek, near present-day Lane, Kansas.He had been enraged by both the sacking of the anti-slavery town of Lawrence several days before and the vicious attack on Charles Sumner on the floor of the U.S. Senate, in which Representative Preston Brooks, of South Carolina, relentlessly beat Sumner with a cane. The killings at Pottawatomie Creek marked the beginning of the bloodletting of the “Bleeding Kansas” period, as both sides of the slavery issue embarked on a campaign of terror, intimidation, and armed conflict that lasted throughout the summer.Three days prior to the massacre, on May 21, he and the “Pottawatomie Company,” an informal militia group, marched toward Lawrence to protect the town from the proslavery men intent on its destruction. After joining with a similar company from the anti-slavery town of Osawatomie, the men traveled north until they received word that they were too late to prevent the attack on the town, which resulted in the destruction of the Free State Hotel and the offices of the free state newspapers, as well as the looting of many homes and businesses.Today in History – May 24, 1856 – John Brown murders follow Americans on the banks of Pottawatomie Creek in Kansas.While camped near Palmyra, he resolved to take his revenge on his proslavery neighbors and enlisted the help of an associate, named James Townsley, to carry him, his sons Frederick, Oliver, Owen, Salmon, and Watson, as well as his son-in-law Henry Thompson back toward Pottawatomie Creek while a sympathetic Theodore Weiner followed on horseback.After crossing Mosquito Creek, the men camped for the night of May 23rd and most of the following day.Around 10:00 p.m. on the 24th, the famous party left their campsite, headed for the cabin of proslavery settler James Doyle, and demanded that he and his sons come outside. They were led a short distance from the cabin, where he shot James Doyle in the head with his pistol as two of his sons hacked James’s sons, Drury and William Doyle, to death with swords. A third son, 16-year-old John Doyle, was spared.The party then traveled to Allen Wilkinson’s home, where, against the protestations of Wilkinson’s wife, who was sick with the measles, they took Wilkinson and hacked him to death, leaving his body alongside the road.They then crossed to the south bank of the creek at Dutch Henry’s ford (named for “Dutch” Henry Sherman) and approached the home of James Harris. Here Brown’s group found several men and questioned them about their views on slavery and whether they had participated in the attack on Lawrence earlier in the week. William Sherman’s answers did not satisfy Brown, and he was killed behind the residence and his body left in the creek. The Browns then disappeared into the night.They did not, however, disappear from the “Bleeding Kansas” scene. News of the attacks inflamed the territory, as both pro- and antislavery families fled for their lives. The irregular warfare extended beyond political motivations – it became personal and mercilessly brutal. Men on both sides continued to organize into armed groups and began patrolling the area in search of their enemies, resulting in engagements such as the Battle of Black Jack (where Brown took a number of proslavery men prisoner) and the Battle of Osawatomie, in which Brown and his men were unable to protect the anti-slavery town from being looted and burned by border ruffians and Brown’s son Frederick was killed.By fall, the new territorial governor, John Geary, had largely restored order in the territory, although violence flared up regularly until 1858 and periodically after that. The Pottawatomie Massacre and the other attacks that marked “Bleeding Kansas” are considered by many historians to have been the opening shots of the Civil War.Research more about this great American Tragedy and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American politician, criminologist and businessman; in 1997 he was the first African-American to be elected mayor of Houston, Texas.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American politician, criminologist and businessman; in 1997 he was the first African-American to be elected mayor of Houston, Texas. He was reelected twice to serve the maximum of three terms from 1998 to 2004.He has had a long career in law enforcement and academia; leading police departments in Atlanta, Houston and New York over the course of nearly four decades. With practical experience and a doctorate from University of California, Berkeley, he has combined research and operations in his career. After serving as Public Safety Commissioner of Atlanta, Georgia, he was appointed in 1982 as the first African-American police chief in Houston, Texas, where he implemented techniques in community policing to reduce crime.Today in our History – May 23, 1982 – Lee Patrick Brown (born October 4, 1937) was named the first black police commissioner of Houston, Texas.His parents, Andrew and Zelma Brown, were sharecroppers in Oklahoma, and Lee Brown was born in Wewoka. His family, including five brothers and one sister, moved to California in the second wave of the Great Migration and his parents continued as farmers.A high school athlete, Brown earned a football scholarship to Fresno State University, where he earned a B.S. in criminology in 1960. That year he started as a police officer in San Jose, California, where he served for eight years. Brown was elected as the president of the San Jose Police Officers’ Association (union) and served from 1965–1966.Brown went on to earn a master’s degree in sociology from San José State University in 1964, and became an assistant professor there in 1968. He also earned a second master’s degree in criminology from University of California, Berkeley in 1968. In the same year, he moved to Portland, Oregon, where he established and served as chairman of the Department of Administration of Justice at Portland State University.In 1972, Brown was appointed associate director of the Institute of Urban Affairs and Research and professor of Public Administration and director of Criminal Justice programs at Howard University. In 1974, Brown was named Sheriff of Multnomah County, Oregon and in 1976 became director of the Department of Justice Services.In 1978 he was appointed Public Safety Commissioner of Atlanta, Georgia, serving to 1982. Brown and his staff oversaw investigation of the Atlanta Child Murders case and increased efforts to provide safety in black areas of the city during the period when murders were committed. A critical element of reform during Brown’s tenure was increasing diversity of the police force. By the time Brown resigned to accept the top police job in Houston, Atlanta’s police force was 20 percent black. In 1982 Brown was the first African American to be appointed as Police Chief to the City of Houston, serving until 1990. He was first appointed by Mayor Kathy Whitmire. The Houston Police Department seemed to be in constant turmoil and badly needed reform. According to one of Brown’s colleagues at Atlanta, … “Everybody knows Lee likes challenges and anyone who knows about the Houston Police Department knows it’s one helluva challenge.” After coming to Houston, Brown quickly began to implement methods of community policing, building relationships with the city’s diverse communities. The Houston Police Officers Union (HPOU) recently published a history describing in more detail how Brown’s reforms were implemented and how it became accepted by the officers as well as the communities they served over a period of years. Initially, the officers were unimpressed by what Brown termed Neighborhood-Oriented Policing (NOP). Old-time officers saw it as simply reverting to a long-discredited policy of “walking a beat,” and claimed the acronym meant “never on patrol.” Brown and his staff divided the city into 23 identifiable “neighborhoods.” Each neighborhood had a small informal office, located in a storefront, where people from the neighborhood were invited to come in and discuss their concerns or problems with one of the officers that served there. Brown emphasized through his officer training sessions that getting feedback from the public was as important as writing up tickets or doing paperwork chores. The neighborhood officers soon recognized the hot spots and the neighborhood “movers and shakers” who could be helpful in preventing problems. Brown was credited with getting more police officers into the neighborhoods during his tenure. Relations between the residents and the police were far better than ever before, with residents becoming willing to work with the police implementing various activities. He was quoted as saying that sixty percent of all cities in the U.S. had adopted some form of NOP by the time he stepped down as Houston’s chief. In December 1989 Brown was named by Mayor David Dinkins as Police Commissioner of New York City, the first non-New Yorker appointed in a quarter of a century as head of the nation’s largest police force. In January 1990, he took over a police force that was seven times the size of Houston’s, with “a complex organization of more than 26,000 officers” and a 346-member executive corps of officers at the rank of captain and above. At the time, the force was 75% white; there were issues of perception of police justice and sensitivity in a city with a population estimated to be half minorities: black, Hispanic and Asian. Brown implemented community policing citywide, which reportedly quadrupled the number of police officers on foot patrol and had a goal of creating a partnership between the police and citizens. The fact that reported crimes were 6.7 percent lower for the first four months of 1992, compared to the previous year, indicated that Brown’s program was having a positive effect, according to the Treadwell article. On the other hand, according to Treadwell, the police department was being criticized for the alleged ineffectiveness of its internal affairs division in the wake of allegations drug dealing and bribery by some officers.Dinkins had appointed a five-member panel to investigate the corruption allegations, and had asked the City Council to establish an all-civilian review board to look at charges of police brutality. Brown was already on record as opposing both actions. Both Brown and Dinkins took great pains to assure reporters that the policy disagreement played no role in Brown’s decision to leave. Brown submitted his resignation from the New York City position effective September 1, 1992. He and Mayor Dinkins held a joint news conference to explain the reason for his sudden departure. Brown stated that he was leaving to care for his wife, who was ill, and to rejoin the rest of his family, who were still in Houston. He added that he had accepted a college teaching position in Houston. In 1993 Brown was appointed by President Bill Clinton as his Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP, or “Drug Czar”), and moved to Washington, DC. The Senate unanimously confirmed his appointment.In the late 1990s, Brown returned to Houston and entered politics directly, running for mayor.In 1997, Brown became the first African American elected as mayor of Houston. During Brown’s administration, the city invested extensively in infrastructure: it started the first 7.5 mile leg of its light-rail system and obtained voter approval for an extension, along with increases in bus service, park and ride facilities, and HOV lanes.It opened three new professional sports facilities, attracting visitors to the city. It revitalized the downtown area: constructing the City’s first convention center hotel, doubling the size of the convention center; and constructing the Hobby Center of the Performing Arts.In addition, it built and renovated new libraries, police and fire stations. Brown initiated a $2.9 billion development program at the city’s airport, which consisted of new terminals and runways; and a consolidated rental car facility; in addition to renovating other terminals and runways, he built a new water treatment plant. Brown also advanced the city’s affirmative action program; installed programs in city libraries to provide access to the Internet; built the state-of-the-art Houston Emergency Communications Center; implemented e-government, and opened new parks. Brown led trade missions for the business community to other countries and promoted international trade. He increased the number of foreign consulates. Brown undertook a massive program to reconstruct the downtown street system and replace the aging underground utility system. The accompanying traffic problems was made a campaign issue by his opponent, three-term city councilman Orlando Sanchez in the 2001 election campaign. In 2001 Brown narrowly survived the reelection challenge and runoff against Sanchez, a Cuban-born man who grew up in Houston. The election characterized by especially high voter turnout in both black and Hispanic districts.Sanchez’ supporters highlighted poor street conditions, campaigning that the “P stands for Pothole,” referring to Brown’s middle initial. Sanchez drove a Hummer as his campaign vehicle during this period, which was adorned with the banner, “With Brown in Town it’s the only way to get around.” Following the death of Houston Fire Captain Jay Janhke in the line of duty, Sanchez gained endorsements from the fire/emergency medical services sector. Brown changed Fire Department policy on staffing as a result of the captain’s death. The Brown-Sanchez election attracted involvement from several national political figures, who contributed to its rhetoric. Brown was endorsed by former Democratic president Bill Clinton while Sanchez was endorsed by then-President George W. Bush, former President George H.W. Bush and his wife, former First Lady Barbara Bush; Rudy Giuliani and a host of other Republicans.Some members of the President’s cabinet campaigned for Sanchez in Houston.The contest had ethnic undertones as Sanchez, a Cuban American, was vying to become the first Hispanic mayor of Houston; he challenged Brown, who was the city’s first African-American mayor. According to the U.S. Census 2000, the racial makeup of the city was 49.3% White (including Hispanic or Latino), 25.3% Black or African American, 0.4% Native American, 5.3% Asian, 0.18% Pacific Islander, 16.5% from other races, and 3.2% from two or more races. 37% of the population was Hispanic or Latino of any race. Voting split along racial and political party lines, with a majority of African Americans and Asians (largely Democrats) supporting Brown, and a majority of Hispanic and Anglo voters (largely Republicans) supporting Sanchez. Brown had 43% in the first round of voting, and Sanchez 40%, which resulted in their competing in a run-off. Chris Bell received 16% of the ballots cast in the first round.Brown narrowly won reelection by a margin of three percentage points following heavy voter turnout in predominantly Black precincts, compared to relatively light turnout in Hispanic precincts, although Hispanic voting in the runoff election was much higher than previously.Brown’s 2001 reelection was one of the last major political campaigns supported by the Houston-based Enron Corporation, which collapsed in a financial scandal days after the election. Research more about this great American and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a Jamaican writer and poet, and was a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a Jamaican writer and poet, and was a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance. He wrote five novels: Home to Harlem (1928), a best-seller that won the Harmon Gold Award for Literature, Banjo (1929), Banana Bottom (1933), Romance in Marseille (published in 2020), and in 1941 a manuscript called Amiable With Big Teeth: A Novel of the Love Affair Between the Communists and the Poor Black Sheep of Harlem which remained unpublished until 2017. He also authored collections of poetry, a collection of short stories, Gingertown (1932), two autobiographical books, A Long Way from Home (1937) and My Green Hills of Jamaica (published posthumously in 1979), and non-fiction, a socio-historical treatise entitled Harlem: Negro Metropolis (1940).His 1922 poetry collection, Harlem Shadows, was among the first books published during the Harlem Renaissance. His Selected Poems was published posthumously, in 1953.He was attracted to communism in his early life, but he always asserted that he never became an official member of the Communist Party USA. However, some scholars dispute that claim, noting his close ties to active members, his attendance at communist-led events, and his months-long stay in the Soviet Union in 1922–23, which he wrote about very favorably. He gradually became disillusioned with communism, however, and by the mid-1930s had begun to write negatively about it. By the late 1930s his anti-Stalinism isolated him from other Harlem intellectuals, and by 1942 he converted to Catholicism and left Harlem, and he worked for a Catholic organization until his death.Today in our History – May 22, 1948 – Festus Claudius “Claude” McKay (September 15, 1889, – May 22, 1948) died.After attending Tuskegee Institute (1912) and Kansas State Teachers College (1912–14), McKay went to New York in 1914, where he contributed regularly to The Liberator, then a leading journal of avant-garde politics and art.The shock of American racism turned him from the conservatism of his youth. With the publication of two volumes of poetry, Spring in New Hampshire (1920) and Harlem Shadows (1922), McKay emerged as the first and most militant voice of the Harlem Renaissance. After 1922 McKay lived successively in the Soviet Union, France, Spain, and Morocco.In both Home to Harlem and Banjo (1929), he attempted to capture the vitality and essential health of the uprooted black vagabonds of urban America and Europe. There followed a collection of short stories, Gingertown (1932), and another novel, Banana Bottom (1933). In all these works McKay searched among the common folk for a distinctive black identity.After returning to America in 1934, McKay was attacked by the communists for repudiating their dogmas and by liberal whites and blacks for his criticism of integrationist-oriented civil rights groups. McKay advocated full civil liberties and racial solidarity.In 1940 he became a U.S. citizen; in 1942 he was converted to Roman Catholicism and worked with a Catholic youth organization until his death. He wrote for various magazines and newspapers, including the New Leader and the New York Amsterdam News. He also wrote an autobiography, A Long Way from Home (1937), and a study, Harlem: Negro Metropolis (1940). His Selected Poems (1953) was issued posthumously. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!