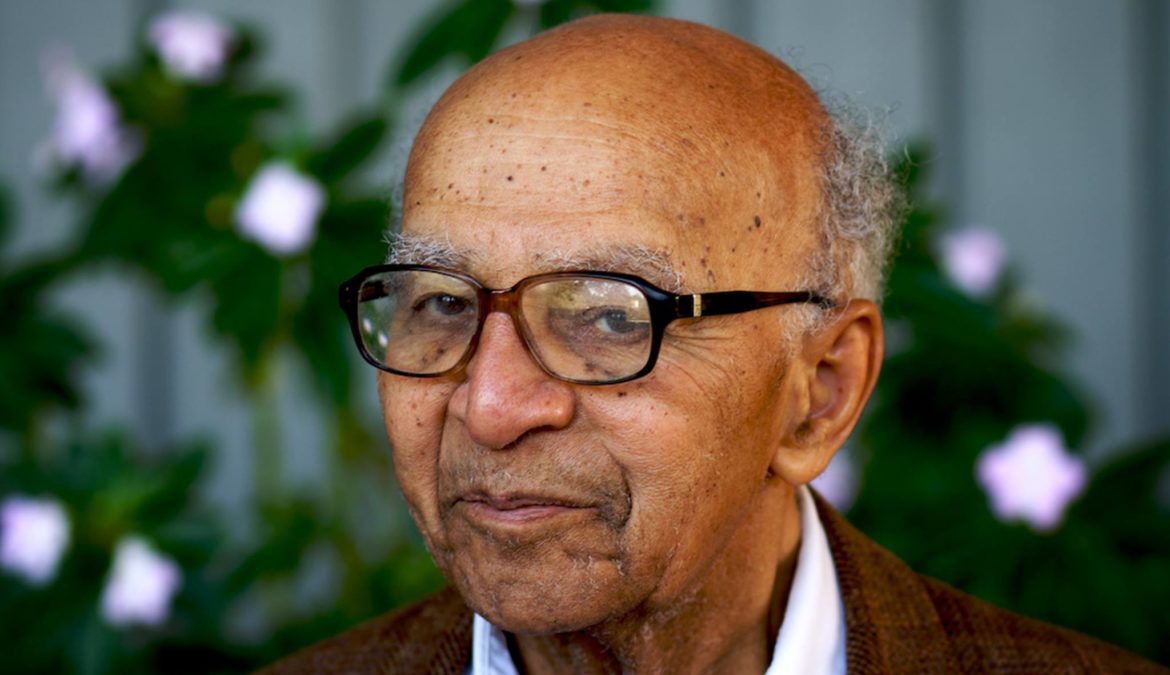

GM – FBF – Although the name Elijah McCoy may be unknown to most people, the enormity of his ingenuity and the quality of his inventions have created a level of distinction which bears his name. One of the most beloved Inventors in history, enjoy!

Remember – “So much time is wasted by trying to be better than others. Dream the impossible because dreams do come true. I am not a star, a star is nothing but a ball of gas. Going against the grain of society is the greatest thing in the world.” – Elijah McCoy

Today in our History – April 29, 1922 – Elijah and Mary McCoy Involved in an automobile accident and both suffered severe injuries.

Elijah McCoy was born in Colchester, Ontario, Canada on May 2, 1844. His parents were George and Emillia McCoy, former slaves from Kentucky who escaped through the Underground Railroad. George joined the Canadian Army, fighting in the Rebel War and then raised his family as free Canadian citizens on a 160 acre homestead.

At an early age, Elijah showed a mechanical interest, often taking items apart and putting them back together again. Recognizing his keen abilities, George and Emillia saved enough money to send Elijah to Edinburgh, Scotland, where he could study mechanical engineering. After finishing his studies as a “master mechanic and engineer” he returned to the United States which had just seen the end of the Civil War – and the emergence of the “Emancipation Proclamation.”

Elijah moved to Ypsilanti, Michigan but was unable to find work as an engineer. He was thus forced to take on a position as a fireman\oilman on the Michigan Central Railroad. As a fireman, McCoy was responsible for shoveling coal onto fires which would help to produce steam that powered the locomotive. As an oilman, Elijah was responsible for ensuring that the train was well lubricated. After a few miles, the train would be forced to stop and he would have to walk alongside the train applying oil to the axles and bearings.

In an effort to improve efficiency and eliminate the frequent stopping necessary for lubrication of the train, McCoy set out to create a method of automating the task. In 1872 he developed a “lubricating cup” that could automatically drip oil when and where needed. He received a patent for the device later that year. The “lubricating cup” met with enormous success and orders for it came in from railroad companies all over the country. Other inventors attempted to sell their own versions of the device but most companies wanted the authentic device, requesting “the Real McCoy.”

In 1868, Elijah married Ann Elizabeth Stewart. Sadly, Elizabeth passed away just four years later. In 1873, McCoy married again, this time his bride was Mary Eleanor Delaney and the couple would eventually settle into Detroit, Michigan together for the next 50 years.

McCoy remained interested in continuing to perfect his invention and to create more. He thus sold some percentages of rights to his patent to finance building a workshop. He made continued improvements to the “lubricating cup.” The patent application described the it as a device which “provides for the continuous flow of oil on the gears and other moving parts of a machine in order to keep it lubricated properly and continuous and thereby do away with the necessity of shutting down the machine periodically.” The device would be adjusted and modified in order to apply it to different types of machinery. Versions of the cup would soon be used in steam engines, naval vessels, oil-drilling rigs, mining equipment, in factories and construction sites.

In 1916 McCoy created the graphite lubricator which allowed new superheater trains and devices to be oiled. In 1920, Elijah established the “Elijah McCoy Manufacturing Company.” With his new company, he improved and sold the graphite lubricator as well as other inventions which came to him out of necessity. He developed and patented a portable ironing board after his wife expressed a need for an easier way of ironing clothes. When he desired an easier and faster way of watering his lawn, he created and patented the lawn sprinkler.

On April 29, 1922, Elijah and Mary were involved in an automobile accident and both suffered severe injuries. Mary would die from the injuries and Elijah’s health suffered for several years until he died in 1929. McCoy left behind a legacy of successful inventions which would benefit mankind for another century and his name would come to symbolize quality workmanship – the Real McCoy! Research more about black Inventors and share with your babies and make it a champion day!