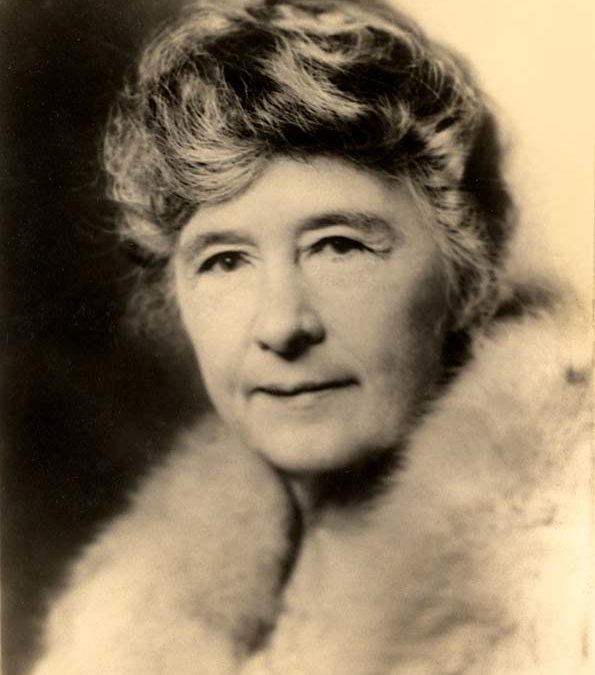

GM – FBF – The story that we will look at today is about a Black female Inventor that you may have never heard of from a state that most people don’t think of going to. I lived and worked there for two years in Morgantown, a University town and the county seat called Monongalia and found the state charming and the people kind and God fearing.

This Inventor took something that was an everyday concern for many people in the state and parts of the nation and discovered a way to prevent it. Like many black inventors there is no record that a manufacturer picked up the patented Invention and used it and it was hard to find out more about this Inventor’s life. Enjoy!

Remember – “You and I may go to Harvard, we may go to York of England, or go to Al Ahzar in Cairo and get degrees from all of these great seats of learning. But we will never be recognized until we recognize our women.” ― Elijah Muhammad

Today in our History – September 30, 1975 – Virgie M. Ammons invented the Fireplace Damper Actuating Tool.

Virgie M. Ammons was born on Dec. 29, 1908, in Gaithersburg, Maryland. At a young age, her family relocated to West Virginia, where she spent the rest of her life. Ammons was a self-employed caretaker and a Muslim woman by faith, attending services in Temple Hills.

Little is known about the life of Virgie Ammons. Ammons filed her patent on August 6, 1974, at which time she was living in Eglon, West Virginia.

Fireplace Damper

Actuating Tool – Patent US 3,908,633

A fireplace damper actuating tool is a tool that is used to open and close the

damper on a fireplace. It keeps the damper from opening or fluttering in the

wind. If you have a fireplace or stove, you may be familiar with the sound of a

fluttering damper.

A damper is an adjustable

plate that fits in the flue of a stove or the chimney of a fireplace. It helps

control the draft into the stove or fireplace. Dampers could be a plate that

slides across the air opening, or it could be fixed in place in the pipe or

flue and turned so the angle allows more or less air flow.

In the days when cooking was done on a stove that was powered by burning wood

or coal, adjusting the flue was a way of controlling the temperature.

Virgie Ammons may be have been familiar with these stoves, given her date of birth. She may also have lived in an area where electric or gas stoves were not common until later in her life. We have no details as to what her inspiration was for the fireplace damper actuating tool.

With a fireplace, opening the damper allows more air to be drawn into the fireplace from the room and convey the heat up the chimney.

More air flow can often

result in more flames, but also in losing more heat rather than warming the

room.

The patent abstract says Ammons’ damper actuating tool addressed the problem of

fireplace dampers that flutter and make noise when gusty winds affected the

chimney Some dampers do not remain fully shut because they have to be light

enough in weight so the operating lever can open them easily. This makes small

differences in air pressure between the room and the upper chimney draw them

open. She was concerned that even a slightly open damper could cause a

significant loss of heat in winter, and could even result in loss of coolness

in summer. Both would be a waste of energy.

Her actuating tool allowed the damper to be closed and held closed. She noted

that when not in use, the tool could be stored next to the fireplace.No

information was found as to whether her tool was manufactured and marketed.

Virgie M. Ammons, 91, Eglon, WV, died July 12, 2000, as the result of injuries sustained in an automobile accident near Aurora, WV. She was a daughter of the late Samuel and Mary (Jones) Claggett. She was also preceded in death by her husband, Charles Ammons, and three brothers, Joseph, Thomas, and Eugene Claggett. Survivors include one daughter, Sharon Ammons, Washington, DC and one sister, Rowena Leva Huggins, Frederick, MD. She was a self-employed caretaker. She was a Muslim by faith and attended church in Temple Hills. Cremation services were provided by the Browning Funeral Home in Kingwood, WV. Research more about this great Black Woman Inventor and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!