GM – FBF – Today’s story is a painful one because it is close to

home being that I am from New Jersey and it was nothing for us to go to NYC or

any of the five sections known as Burrows. In the 1980s, several racially

motivated attacks dominated the headlines of New York City newspapers. On

September 15, 1983, artist and model Michael Stewart died on a lower Manhattan

subway platform from a chokehold and beating he received from several police

officers. A year later, on October 29, an elderly grandmother, Eleanor Bumpers,

was murdered by a police officer in her Bronx apartment as he and other

officers tried to evict her.

Later that year, on December 22, a white man, Bernhard Goetz,

shot and seriously wounded four black teenagers he thought were going to rob

him on a subway train in Manhattan. The Howard Beach racial incident in late

1986 propelled the predominantly Italian and Jewish community into the national

spotlight, exposing racial hatred in New York City. Enjoy!

Remember – “I could recall 25 years ago as a kid, I would not

recommend anyone black stopping there,” said Representative Gregory W. Meeks,

who is black and represents Old Howard Beach, east of Cross Bay Boulevard.

“Today, it’s definitely a different place.”

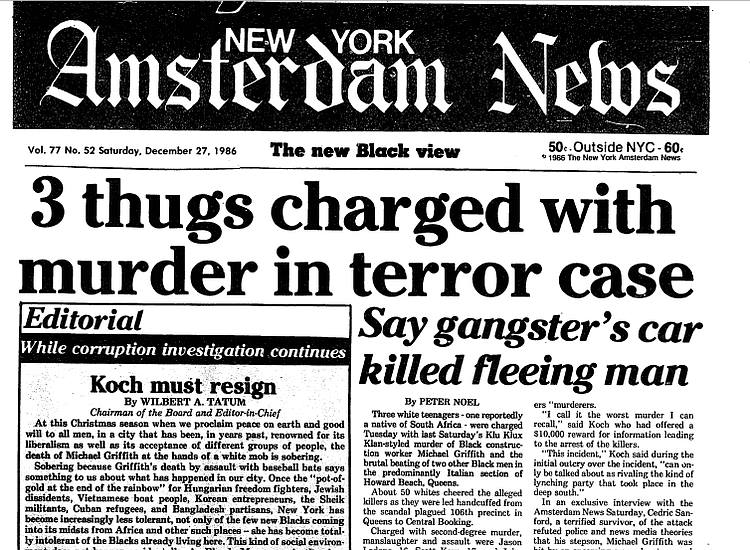

Today in our History – On December 20, 1986, a black man was

killed and another was beaten in Howard Beach, Queens, New York, United States

in a racially charged incident that heightened racial tensions in New York

City.

The man attacked was 23-year-old Michael Griffith (March 2, 1963

– December 20, 1986), who was from Trinidad and had immigrated to the United

States in 1973, and lived in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. He was killed after being

hit by a car as he was chased onto a highway by a mob of white youths who had

beaten him and his friends. Griffith’s death was the second of three infamous

racially motivated killings of black men by white mobs in New York City in the

1980s. The other victims were Willie Turks in 1982 and Yusuf Hawkinsin 1989.

Late on the night of Friday, December 19, 1986, four black men,

Michael Griffith, 23; Cedric Sandiford, 36; Curtis Sylvester and Timothy

Grimes, both 20, were riding in a car when it broke down in a deserted stretch

of Cross Bay Boulevard near the Broad Channelneighborhood of Queens. Three of

the men walked about three miles north to seek help in Howard Beach, a mostly

white community, while Sylvester remained behind to watch the car. They argued

with some white teens who were on their way to a party, then left.

By 12:30 a.m. on the 20th, the men reached the New Park

Pizzeria, near the intersection of Cross Bay Boulevard and 157th Avenue. After

a quick meal the men left the pizzeria at 12:40 a.m. and were confronted by a

group of white men, including the group they had earlier confronted. When Sandiford,

Grimes, and Griffith left the restaurant at 12:40 a.m., a mob of twelve white

youth awaited them with baseball bats, tire irons, and tree limbs. The gang,

led by Jon Lester, 17, included Salvatore DeSimone, 19, William Bollander, 17,

James Povinelli, 16, Michael Pirone, 17, John Saggese, 19, Jason Ladone, 16,

Thomas Gucciardo, 17, Harry Bunocore, 18, Scott Kern, 18, Thomas Farino, 16,

and Robert Riley, 19.

Racial slurs were exchanged and a fight ensued. Sandiford and

Griffith were seriously beaten; Grimes escaped unharmed. The mob attacked

Griffith and Sandiford. Grimes, who drew a knife on the angry mob, escaped with

minor injuries. Sandiford begged, “God, don’t kill us” before Lester knocked

him down with a baseball bat. With the mob in hot pursuit, the severely beaten

Griffith ran the nearby Belt Parkway where he jumped through a small hole in a

fence adjacent to the highway. As he staggered across the busy six-lane

expressway, trying to escape his attackers, he was hit and instantly killed by

a car driven by Dominic Blum, a court officer and son of a New York police

officer. His body was found on theBelt Parkway at 1:03 a.m.

The incident sparked immediate outrage in New York’s African

American community, prompting black civil rights activist Reverend Al Sharpton

to organize several protests in Howard Beach, as well as the Carnarsie and Bath

Bay sections of Brooklyn. Other leaders, including newly elected black

Congressman Floyd Flake and Brooklyn activists Sonny Carson and Rev. Herbert

Daughtry, called for boycotts of all white-owned Howard Beach businesses.

New York Governor Mario Cuomo appointed a special prosecutor,

Charles J. Hynes, who brought manslaughter, second degree murder, and first

degree assault charges against four leaders of the mob, Jon Lester, Jason

Ladone, Scott Kern and Michael Pirone. The other men were charged with lesser

offenses.

Griffith’s death provoked strong outrage and immediate

condemnation by then-Mayor of New York City Ed Koch, who referred to the case

as the “No. 1 case in the city”. Two days after the event, on

December 22, three local teenagers, Jon Lester, Scott Kern, and Jason Ladone,

students at John Adams High School, were arrested, and charged with

second-degree murder. The driver of the car that struck Griffith, 24-year-old

Dominick Blum, was not charged with any crime; a May 1987 grand jury did not

return criminal charges against him.

To protest the killing of Griffith, 1,200 demonstrators marched

through the streets of Howard Beach on December 27, 1986. A heavy NYPD presence

kept angry white locals, who were screaming at the crowd of marchers, in check.

The Griffith family, as well as Cedric Sandiford, retained the services of

Alton H. Maddox and C. Vernon Mason(who was later disbarred), two attorneys who

would become involved in the Tawana Brawley affair the following year. Maddox

raised the ire of the NYPD and Commissioner Benjamin Ward by accusing them of

trying to cover up facts in the case and aid the defendants.

After witnesses repeatedly refused to cooperate with Queens D.A.

John J. Santucci, Governor of New York Mario Cuomo appointed Charles Hynes

special prosecutor to handle the Griffith case on January 13, 1987. The move

came after heavy pressure from black leaders on Cuomo to get Santucci, who was

seen as too partial to the defendants to prosecute the case effectively, off

the case.

Twelve defendants were indicted by a grand jury on February 9,

1987, including the original three charged in the case. Their original

indictments had been dismissed after the witnesses refused to cooperate in the

case.

After a lengthy trial and 12 days of jury deliberations, the

three main defendants were convicted on December 21, 1987 of manslaughter, a

little over a year after the death of Griffith. Kern, Lester and Ladone were convicted

of second-degree manslaughter and Michael Pirone, 18, was acquitted. Ultimately

nine people would be convicted on a variety of charges related to Griffith’s

death.

On January 22, 1988, Jon Lester was sentenced to ten to thirty

years’ imprisonment. On February 5, Scott Kern was sentenced to six to eighteen

years’ imprisonment, and on February 11, 1988, Jason Ladone received a sentence

of five to fifteen years’ imprisonment.

In December 1999, the block where Griffith had lived was given

the additional name “Michael Griffith Street.”

Jason Ladone, then 29, was released from prison in April, 2000 after serving 10

years, and later became a city employee. He was arrested again in June 2006, on

drug charges. In May 2001, Jon Lester was released and deported to his native

England where he studied electrical engineering and started his own business.

He died on August 14, 2017 at age 48 of what some suspect was a suicide. He

left behind a wife and three children.[10] Scott Kern was released from prison,

last of the three main perpetrators, in 2002.

In 2005 the Griffith case was

brought back to the public’s attention after another racial attack in Howard

Beach. A black man, Glenn Moore, was beaten severely with a metal baseball bat

by Nicholas Minucci, who was convicted of hate crimes in 2006. The case was

revisited yet again by the media, after the death of Michael Sandy, 29, who was

beaten and hit by a car after being chased onto the Belt Parkway in Brooklyn,

New York, in October 2006. Research more about Black harassment in communities

and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!