GM – FBF – I was born a slave-was the child of slave

parents-therefore I came upon the earth free in God-like thought, but fettered

in action. – Elizabeth Keckley

Remember – When I heard the words, I felt as if the blood had

been frozen in my veins, and that my lungs must collapse for the want of air.

Mr. Lincoln shot! – Elizabeth Keckley

Today in our History – February 24, 1818 – (If you thought that

Lee Daniels’ The Butler – The life of Eugene Allen in the White House as a

butler which Forest Whitaker and Oprah Winfrey co – stared) Read this story

which happened 100 years before that. – There’s a nighttime scene in Steven

Spielberg’s Lincoln in which the president tells an African-American woman

about his uncertainty over what freedom will bring emancipated slaves after the

Civil War.

The woman, whom he addresses as “Mrs. Keckley,” makes brief but

puzzling appearances throughout the film: outside the Lincoln bedroom in the

White House, in the gallery of the House of Representatives beside Mary Todd

Lincoln and as the sole companion of the Lincolns at an opera. In this

conversation, Keckley asks Lincoln pointedly for his personal feelings toward

her race. “I don’t know you, Mrs. Keckley,” he begins. And neither does the

viewer, who is left to ponder how this woman could have come to address the

president so candidly, and what may have moved Lincoln to speak so frankly to

her about his misgivings.

But this dramatization is deceiving. Abraham Lincoln knew Elizabeth Keckley

well, both as his wife’s most intimate friend and as a leader among free black

women in the North. In just five years she rose from slavery in St. Louis to

intimacy with the first family in Washington. Her remarkable life story and

accomplishments ranked with those of contemporaries Harriet Tubman and

Sojourner Truth. But unlike them, her name faded into the shadows of history,

much like her shadowy presence in the movie. And so the question remains: Who

was Mrs. Keckley?

Elizabeth Keckley (sometimes spelled Keckly) was born on the

plantation of Armistead and Mary Burwell outside Petersburg, Va., in February

1818. She never knew her precise birth date, a detail too trifling for entry

into slave records. But her birth engaged more than the passing interest of

Armistead Burwell, who was both her master and her father. Elizabeth’s mother

was Agnes Hobbs, a literate slave and the Burwell family seamstress.

Liaisons between masters and female slaves were common and

usually forced. As slaves were mere property, Southern society did not regard

this as rape or adultery. But wives of philandering slaveholders had little

regard for the offspring of such illicit encounters, particularly when the

children bore a resemblance to their fathers—as did light-skinned “Lizzie”

Hobbs. Mary Burwell put Lizzie to work at age 4 watching over the Burwells’

baby daughter. The responsibility was too great for a child. One day Lizzie

accidentally rocked the cradle too hard, spilling the infant to the floor.

Perplexed and frightened, Lizzie tried to scoop the baby back into the cradle

with a fireplace shovel just as Mary Burwell entered the room. Infuriated, Mrs.

Burwell ordered the overseer to beat Lizzie. “The blows were not administered

with a light hand, and doubtless the severity of the lashing has made me

remember the incident so well,” Keckley later recalled. “This was the first

time I was punished in this cruel way, but not the last.”

Elizabeth Hobbs lived a turbulent early life, with both the

anguish common to slavery and privileges denied most slaves. Her mother taught

her to sew, and somehow, probably with the Burwells’ permission, she learned to

read and write. In 1836 Armistead Burwell loaned Elizabeth and her mother to

his eldest son Robert, a Presbyterian minister living in Hillsborough, N.C.

Robert Burwell’s wife considered Elizabeth too strong-willed for a slave and

sent her to William J. Bingham, the village schoolmaster known for his cruelty,

to have the pride beaten out of her. Calling Elizabeth into his study, Bingham

grabbed a lash and told her to strip naked. Elizabeth refused. “Recollect, I

was eighteen years of age, was a woman fully developed, and yet this man coolly

bade me take down my dress.” Bingham overpowered her, and she staggered home

covered with bloody welts and deep bruises. After beating her a second time,

Bingham broke down and begged her forgiveness. After Bingham faltered, the

Reverend Burwell himself beat Elizabeth, striking her so hard with a chair leg

that his wife begged him to desist from further punishments.

No sooner did the beatings end than a white neighbor named

Alexander Kirkland raped Elizabeth. He used her for four years. In 1840

Elizabeth gave birth to a boy, whom she named George Kirkland. Although

three-quarters white, he was a slave like his mother.

After these ordeals, Elizabeth’s fortunes improved. She and her

son returned to Petersburg as the property of Armistead Burwell’s daughter Anne

Garland and her husband Hugh. Anne treated her illegitimate half-sister kindly

and encouraged her progress as a seamstress and dressmaker.

Garland’s business went bankrupt in 1847. He moved his family to

St. Louis and opened a law practice, which also foundered. Elizabeth and her

mother helped support the Garlands by making dresses for white socialites. In

exchange, the Garlands permitted Elizabeth to mingle with the large free black

population of St. Louis. In 1855 they agreed to manumit her and young George

for $1,200, which Elizabeth borrowed from a sympathetic white client.

That November, Elizabeth married James Keckley. She prospered as

a dressmaker and sent her son to the recently founded Wilberforce University in

Ohio. But her marriage broke down after Elizabeth learned her husband, who had

represented himself as a free black man, was in fact a “dissolute and debased”

slave who proved nothing but a “source of trouble and a burden” to her. In

early 1860, Elizabeth Keckley left her husband and moved to Baltimore, hoping

to teach dressmaking to young black women. Her plan failed, and “with scarcely

enough to pay my fare to Washington,” Elizabeth traveled to the nation’s

capital in search of new opportunities.

It was a life-changing decision. Elizabeth found work in

October 1860 as a seamstress for a “polite and kind” shop-owner whose customers

included the leading ladies of Washington. He offered her a generous

commission. Elizabeth’s clients delighted in her designs, and her popularity

grew. She rented an apartment in a middle-class black neighborhood and soon

counted Mary Anna Randolph Custis Lee, wife of Colonel Robert E. Lee, and

Varina Davis, wife of Senator Jefferson Davis, among her clients.

During the secession winter of 1860-61, Elizabeth went to the

Davis residence daily to make clothing for Varina and her children and

frequently overheard Senator Davis’ political discussions with Southern

colleagues. When the Davises left Washington in late January 1861, Varina asked

Elizabeth to come South with the family, warning that in the event of war Northerners

would blame blacks for the conflict and “in their exasperation treat you

harshly.” Elizabeth politely declined, and they parted on good terms.

But Elizabeth was not long without a distinguished “patroness.”

With ambition equal to her talent, she sought work in the White House. “To

accomplish this end, I was ready to make almost any sacrifice consistent with

propriety.” As it turned out, all she needed to do to gain an interview with

the new first lady was to make a gown on short notice for Margaret McClean,

daughter of future Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner and a mutual friend of Varina

Davis and Mary Todd Lincoln.

Elizabeth called on the first lady on March 5, 1861, the day

after President Lincoln’s inauguration. The interview was short; learning

Elizabeth had worked for Varina Davis, whose wardrobe was widely admired, Mary

Lincoln hired her on the spot, asking only that Elizabeth keep her rates

reasonable because the Lincolns were “just arrived from the West and poor.”

Mary made no friends in Washington society, but the dresses Elizabeth created

for her caused quite a stir. The wives of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles became regular customers, and Elizabeth

made mourning gowns for the widow of Senator Stephen A. Douglas. But most of

her income came from working on Mary Lincoln’s expanding wardrobe. With her

earnings, Elizabeth opened a shop and hired several assistants. Mary preferred

to go to Elizabeth’s rooms for her fittings, as did Mary Jane Welles and Ellen

Stanton. Elizabeth disapproved of their visits, saying later, “I always thought

that it would be more consistent with their dignity to send for me instead of

their coming to me.”

Meanwhile, her son had managed to pass himself off as white to

enlist in the Union Army at the outbreak of the war. His time in the service

was short; George Kirkland died August 10, 1861, at the Battle of Wilson’s

Creek, Mo. Mary Lincoln heard the news while vacationing in New York and sent

Elizabeth a “kind womanly letter” of condolence, a mark of the growing intimacy

between them.

That the spoiled daughter of a Kentucky slave owner would form a

close bond with an ex-slave was less surprising than it appeared. Mary was a

friendless outsider in Washington. Fair-skinned, always immaculately dressed,

literate and “courteous to the Nth degree,” a White House housekeeper observed,

Elizabeth was “the only person in Washington who could get along with Mrs.

Lincoln when she became mad with anyone for talking about her and criticizing

her husband.” Thirty-seven years of bondage had taught Elizabeth to accept fits

of temper and irrational outbursts far more severe than Mary Lincoln’s.

The death of the Lincolns’ 11-year-old son Willie in February

1862 drew Mary closer to Elizabeth. Suffering from paroxysms of grief beyond

her husband’s capacity to endure, Mary found refuge in her dressmaker’s calm

and steady presence. A pattern emerged that would characterize the next three

years of Elizabeth’s life. She spent much of her time at the White House, often

returning home only to sleep or give brief instructions to her employees. She

cared for the Lincolns’ youngest son Tad, who was often ill, ministered to Mary

during her frequent bouts of headaches and nervous exhaustion, and earned the

respect of President Lincoln, who addressed her as “Madame Elizabeth.”

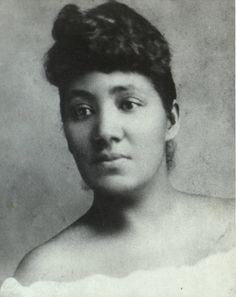

When slavery was abolished in the District of Columbia in April

1862, a New York Post correspondent introduced the nation to “Lizzie, a

stately, stylish woman,” in an article about successful free blacks in

Washington. “Her features are perfectly regular, her eyes dark and winning;

hair straight, black, shining. A smile half-sorrowful and wholly sweet makes

you love her face as soon as you look on it. It is a face strong with intellect

and heart. It is Lizzie who fashions those splendid costumes of Mrs. Lincoln,

whose artistic elegance have been so highly praised. Stately carriages stand

before [Keckley’s] door, whose haughty owners sit before Lizzie docile as lambs

while she tells them what to wear. Lizzie is an artist, and has such a genius

for making women look pretty, that not one thinks of disputing her decrees.”

Lincoln spoke freely in Elizabeth Keckley’s presence. One

afternoon while she was dressing Mary Lincoln for a reception, the president entered

the room. Glancing onto the lawn where Tad played with two goats, he turned

to Elizabeth and asked, “Madame Elizabeth, you are fond of pets, are

you not?” “Oh yes, sir,” she answered. “Well, come here and look at my two

goats. I believe they are the kindest and best goats in the world. See how they

skip and play in the sunshine.” After one sprang into the air, Lincoln asked

Elizabeth if she had ever seen “such an active goat.” Musing a moment, he

continued, “He feeds on my bounty and jumps with joy. Do you think we should

call him a bounty-jumper? But I flatter the bounty jumper. My goat is far above

him. I would rather wear his horns and hairy coat than demean myself to the

level of the man who plunders the national treasury in the name of patriotism.”

“Come, ’Lizabeth,” Mary scolded. “If I get ready to go down this evening I must

finish dressing myself, or you must stop staring at those silly goats.”

“Mrs. Lincoln was not fond of pets, and she could not understand

how Mr. Lincoln could take so much delight in his goats,” Keckley remembered.

“After Willie’s death, she could not bear the sight of anything he loved, not

even a flower.”

Mary buried her unrelenting anguish in lavish spending on

clothing and jewelry. Elizabeth accompanied her on shopping trips to New York

and Boston, remaining behind in the cities for days at a time to settle orders

with merchants. Despite the demands of being the first lady’s companion, she

carved out a place as a leader among the capital’s free black community. A

chance stroll past a charitable event for wounded soldiers in August 1862

suggested an idea. Forty thousand ex-slaves freed by advancing Union armies

thronged the capital, where they lived in squalor. “If the white people can

give festivals to raise funds for the relief of suffering soldiers,” she mused,

“why should not the well-to-do colored people go to work to do something for

the benefit of suffering blacks?” Two weeks later the Contra-band Relief

Association was born, with Elizabeth as president. Mary Lincoln was first to

subscribe with a $200 donation. President Lincoln also contributed. Northern

abolitionists raised funds and contributed clothing and blankets. Frederick

Douglass lectured on the association’s behalf and obtained contributions from

anti-slavery societies in Great Britain.

Under Elizabeth’s leadership the association distributed food,

clothing and other essentials to freedmen, sheltered them and brought teachers

to schools built for them. Fundraisers attracted prominent speakers such as

Douglass and Wendell Phillips. The organization also hosted Christmas dinners

for sick and wounded soldiers of both races.

“Some of the freedmen and freedwomen had exaggerated ideas of

liberty. To them it was a beautiful vision, a land of sunshine, rest, and glorious

promise,” she wrote. “Since their extravagant hopes were not realized, it was

but natural that many of them should feel bitterly their disappointment.

Thousands of the disappointed huddled together in camps, fretted and pined like

children for the ‘good old times.’ In visiting them they would crowd around me

with pitiful stories of distress. Often I heard them declare that they would

rather go back to slavery in the South and be with their old masters than to

enjoy the freedom of the North. I believe they were sincere, because dependence

had become a part of their second nature, and independence brought with it the

cares and vexations of poverty.”

As the war dragged on and her husband had neither the time nor

patience to indulge her roller-coaster emotions, Mary Lincoln grew increasingly

dependent on Elizabeth, withholding little. When it appeared Lincoln might lose

the 1864 election, she tearfully revealed her crushing financial burden. “The

president glances at my rich dresses and is happy to believe that the few

hundred dollars that I obtain from him supply all my wants,” she said. “If he

is elected, I can keep him in ignorance of my affairs, but if he is defeated,

then the bills will be sent.”

Lincoln’s re-election eased her worry. After Richmond fell in

April 1865, Mary invited Elizabeth to accompany her and the president on a

visit to City Point, Va., aboard the River Queen. From there they traveled to

Richmond, where Elizabeth visited the vacant Confederate Senate chamber and sat

in the chair Jefferson Davis sometimes occupied. When the presidential party

moved on to Petersburg, Elizabeth searched for childhood acquaintances while

the president inspected the troops. She found a few, but was sorry she had

come. “The scenes suggested painful memories, and I was not sorry to turn my

back again upon the city,” she confessed.

Greater pain awaited, and soon. On the evening of April 11,

Elizabeth peered out a White House window at the president, who stood on an

open balcony a short distance away. Lincoln had just begun to speak to a large

crowd about his plans for Reconstruc-tion. In one hand he held his speech, in

the other a candle. Its flickering shadow obscured the words, and Lincoln

passed the candle to a journalist behind him. As the candlelight fell full on

the president, Elizabeth shivered. “What an easy matter it would be to kill the

president as he stands there,” she whispered to a companion. “He could be shot

down from the crowd, and no one be able to tell who fired the shot.”

The next morning Elizabeth shared her fear with Mary, who

answered sadly, “Yes, yes, Mr. Lincoln’s life is always exposed. No one knows

what it is to live in constant dread of some fearful tragedy. I have a

presentiment that he will meet with a sudden and violent end. I pray to God to

protect my beloved husband from the hands of the assassin.”

Three nights later the president lay dying in the Petersen House

across the street from Ford’s Theatre. Mary ordered messengers to bring

Elizabeth to her, but they all got lost in the tumult outside the theater. The

next morning Elizabeth came to the White House. She found the first lady

prostrate with grief and in desperate need of her companionship. For the next

six weeks she remained with Mary, sleeping in her room and, as Mary said, “watching

faithfully by my side.”

After Lincoln’s assassination, Mary’s debts came due. From

Chicago, where she had moved with Robert Todd Lincoln, she hectored Elizabeth

with sorrowful letters of her financial plight. In September 1867, she enlisted

Elizabeth in a scheme to sell her clothing and jewelry in New York City.

Together they visited merchants, Mary traveling heavily veiled and incognito as

Mrs. Clark of Chicago. Sales were few, and she was found out. The press

pilloried her as insane, “a mercenary prostitute” who dishonored her late

husband’s memory. Retreating to Chicago, she left Elizabeth to negotiate with

her creditors. The letters from Chicago resumed, each begging Elizabeth to stay

in New York until she settled Mary’s affairs. Elizabeth agreed, shutting down

her Washington business and taking in sewing to make ends meet. While Elizabeth

labored on her behalf in New York, Mary inherited $36,000 in bonds from her

late husband’s probated estate. She had promised Elizabeth a tidy sum for their

joint venture, but sent her nothing.

With her own livelihood imperiled and her reputation sullied by

the “Old Clothes” affair, Elizabeth decided to write her memoir in

collaboration with James Redpath, a book promoter and white friend of Frederick

Douglass.

In the spring of 1868 the prominent New York publisher Carleton and Company

released Behind the Scenes: Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White

House. Elizabeth’s avowed purpose was to “place Mrs. Lincoln in a better light

before the world” by showing the innocent “motives that actuated us” in the

“New York fiasco” and also protect her own good name. “To defend myself I must

defend the lady I served,” she wrote boldly in the introduction.

Instead, Elizabeth destroyed herself. Her frank revelations of Mary

Lincoln’s erratic behavior and spendthrift ways while in the White House

violated Victorian standards of friendship and privacy and of race relations.

Without Elizabeth’s permission, Redpath had inserted as an appendix Mary’s

correspondence with Elizabeth about her New York scheme, letters that showed

Mary at her unstable worst. Robert Lincoln denounced the book and may have

tried to suppress sales. A New York book critic wondered if American literary

taste had fallen “so low grade as to tolerate the backstairs gossip of Negro

servant girls.” Washington newspapers warned white families not to confide in

their black housekeepers. Someone penned a cruel parody titled Behind the

Seams; by a Nigger Woman who Took Work in From Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Davis and Signed

with an “X,” the Mark of “Betsey Kickley” (Nigger). Mary Lincoln dissolved her

friendship with the “colored historian,” as she now referred to Elizabeth

Keckley.

Mary, born the same year as

Elizabeth, died in 1882. Elizabeth outlived her by 25 unhappy years. Behind the

Scenes cost Elizabeth her white clientele. She scraped by teaching young black

seamstresses, and in 1890 sold her cherished collection of Lincoln mementos for

a paltry $250. Friends arranged Elizabeth’s appointment to the faculty of Wilberforce

University in 1892 as head of the Department of Sewing and Domestic Service,

but she taught only briefly before a mild stroke ended her working life.

Elizabeth spent her final years in the National Home for Destitute Colored

Women and Children, founded during the Civil War in part with funds from her

Contraband Relief Association. She never recovered from her falling-out with

Mary Lincoln. She hung Mary’s portrait over her bed and made a quilt from

pieces of her dresses. Like Mary, she suffered constant headaches and frequent

crying spells. In 1907, at the age of 89, Elizabeth Keckley died alone and

nearly forgotten. She deserved better. During the Civil War, she had lifted

much of the weight of Mary Lincoln’s grief and instability from the president’s

shoulders. For that alone, Elizabeth Keckley merits the gratitude of history. I

am a Lincoln follower and could not wait til it was time to share this with

you. Resaech about this great American and share with your babies. Make it a

champion day!