GM – FBF – Law and Order was at low on this HBSU Campus!

Remember – The streets looked like a war zone – Willie Ernest Grimes

Today in our History – May 21, 1969 – Police and National Guardsmen fired on North Carolina A&T Campus.

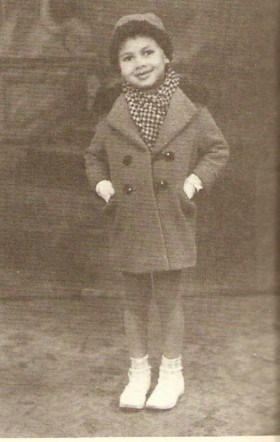

Willie Ernest Grimes was born in Winterville, North Carolina, a rural eastern town in Pitt County just outside Greenville. He grew up in a close knit family with his four siblings. Willie and his brother, George, who was four years younger, were the two youngest children and were especially close. His parents, Joe and Ella, were farmers.

Half the teachers at the high school Willie attended were A&T grads; therefore, it seemed like a natural decision for him to attend college there. Willie was known as a friendly and “good guy” among his classmates on campus. He worked part time and joined the Pershing Rifles, an Army ROTC fraternity.

In April 1969, the death of their grandfather brought the five Grimes’ siblings together. Although this was a sad occasion, Willie enjoyed being with his family and loved the home cooked meals that were prepared while he was there. He wondered when would he get home cooking like this again. When it was time for him to leave to go back to school, Willie told his family, “I’ll see you later” because his father always told him not to say goodbye.

On Wednesday night, May 21, 1969 Willie called home to tell his folks he had cashed his income tax refund check; his dad said that he would pick him up that week-end to take him home because the spring semester was nearly over. Later that night, he talked with his friends about the chaos taking place on A&T’s campus.

Three weeks earlier, at nearby Dudley High School, protests had erupted because of the results of a student council election. Claude Barnes, a junior at Dudley, had spoken out against the differences in the segregated schools and other issues of inequality and was considered a militant by Dudley High School administrators. By this time, student council elections had rolled around and because of his outspokenness, the administrators refused to let his name appear on the student council ballot but students wrote it in anyway which resulted in the win by Barnes. This victory was declared illegal by administrators causing Barnes and four of his friends to walk out of school and picket in protest. The next day nine students walked out.

Barnes has said he thinks the protest would have run its course but school authorities called the police which encouraged others to join the protest and on May 16, nearly four hundred students boycotted classes. Leaders in the African American community had asked school authorities to recognize Barnes’ election win; however, they would not.

On May 19, protests had exploded into violence and after two days, the violence got worse as police fired tear gas to disperse students as they threw rocks at the building where a representative from the schools’ central administration had set up an office. The hostilities spread to A&T’s campus where hundreds of N.C. A&T and Dudley High School students, including Barnes, were tear-gassed and beaten and/or arrested. Gunfire erupted between police and North Carolina National Guard troops on one side and people on the A&T campus on the other.

Willie and his friends decided to walk to Summit Avenue, less than a mile away, to buy food at a local fast food restaurant. They left Scott Hall to walk across campus. As they neared the edge of campus, gunshots were fired and Willie was hit near Carver Hall on A&T’s campus. Witnesses said someone fired on him from a car. Others said the shots came from an unmarked police car which was emphatically denied by the police. In the early hours on May 22, a speeding car carried Willie to Moses Cone Hospital where he was declared dead on arrival at 1:30 a.m. It was concluded that he died within fifteen to twenty minutes from a bullet that was lodged in the base of his brain.

Joe Grimes went to Greensboro the next morning and took Willie’s body back to Winterville.

The funeral of Willie Ernest Grimes, a twenty-year-old North Carolina A&T State University sophomore was attended by two thousand people, including many A&T students who came to pay their respects. The funeral was held at his high school to acommodate all who came. Grimes’ killing and the shootings of five police officers and two other students have never been solved.

Willie Grimes was described as “a studious young man… neither a militant nor an activist”. A memorial in his honor is located at the Memorial Student Union on the campus of A&T. Ella Grimes, Willie’s mother, and his sister, Gloria, still live in Winterville. Willie’s brother, George, is an A&T graduate. Like his brother, George joined the Army ROTC and pledged the Pershing Rifles fraternity. Make it a champion day!