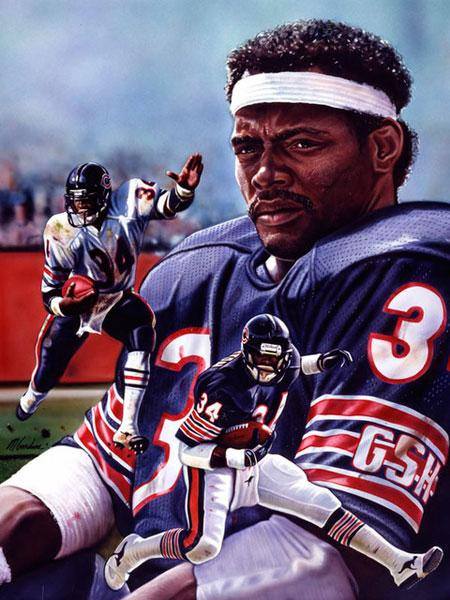

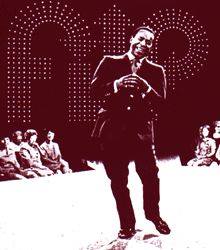

GM – FBF – Today’s story is about a man who could inspire you and got the best out of you in practice or in a game. He graduated in tiny Jackson State University but people knew then he was special. It always wasn’t easy for him until he had an offense line. Then the man turned in his greatness. His personal story was sad as I watched him maybe like some of you tell the world that he had cancer and would die. He broke down on the television and cried because he didn’t want to die. He will always be remembered because the NFL has a Man of The Year trophy named after him. Enjoy the story!

Remember – “I am happy to say that everyone that I have met in my life, I have gained something from them; be it negative or positive, it has enforced and reinforced my life in some aspect.” – Walter Payton

Today in our History – November 1 – Walter Payton dies from cancer.

Former Chicago Bears running back Walter Payton, the NFL’s all-time rushing leader and a man who ran with gritty determination and defiance that belied his nickname “Sweetness,” died from cancer of the bile duct.

Payton, looking shockingly frail and gaunt, announced at an emotional news conference Feb. 2 he was suffering from primary sclerosing cholangitis, a rare liver disease he said at the time could be cured only by a transplant.

But Greg Gores, a liver specialist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said today at a news conference at Bears headquarters in Lake Forest, Ill., that further evaluation of Payton’s illness had indicated “a diseased malignancy of the bile duct.”

Gores said Payton had undergone chemotherapy and radiation treatment in recent months in an attempt to stem the cancer. He added that because of the “aggressive nature” of the malignancy and its spread to other areas, “a liver transplant was no longer viable. . . . He made an informed decision regarding additional therapy.”

Surrounded by his wife, Connie, and two children, Jarrett and Brittney, Payton died shortly after noon at his home in Barrington, Ill., a suburb of Chicago, the city he captivated with his on-field heroics for 13 seasons, including a Super Bowl championship at the end of a 15-1 season in 1985.

“He’s the best football player I’ve ever seen. At all positions, he’s the best I’ve ever seen,” said Mike Ditka, who coached Payton for six of current Saints coach’s 11 years with the Bears, including the 1985 Super Bowl season. “There are better runners than Walter. But he’s the best football player I ever saw. To me, that’s the ultimate compliment.”

In a career that began with a debut of minus-eight yards in

eight carries in the first game of his rookie season,

Payton rushed for 16,726 yards, breaking the record held by fellow Hall of

Famer Jim Brown and a record as revered in his sport as Hank Aaron’s 744 home

runs in baseball.

Payton was named to the Hall of Fame in January 1993 –– first year of eligibility – and was believed to be a unanimous choice by selectors.

Payton, 5 feet 10 and 200 pounds, was an awesome physical specimen who came into the league in 1975 as the Bears’ first-round choice out of Jackson State in Mississippi, the fourth overall pick that year. He finished fourth in the Heisman Trophy voting in a year when Ohio State running back Archie Griffin won it for the second straight season. Payton got little support, mostly because Jackson State, a predominately black school, played a weaker Division I-AA schedule.

Payton gained 3,563 yards and scored 66 touchdowns over his college career and once scored 46 points in a game. He led the nation in scoring in 1973 with 160 points, and his 464 career points were an NCAA record.

But that was merely a prelude to a remarkable NFL career that

ended in early 1988, when the Washington Redskins knocked the Bears out of the

playoffs for the second straight season.

“My first year coaching with the Rams, we played the Chicago Bears in the

[NFC] championship game, and I got to see first-hand what a great player Walter

Payton was,” said Redskins Coach Norv Turner. “He was obviously much,

much more than that – what a role model for anyone who ever wanted to play in

this league or anyone who wanted to compete, and what a role model on and off

the field.”

Payton was a driven athlete, a player who conditioned himself for the rigors of the game by running up steep hills in the offseason to the point of total exhaustion. He had arms like anvils, the thighs of Mr. Universe and an iron will. He missed only one game because of injury in his entire career when a coach, over Payton’s protest, rested him because of a sore ankle his rookie season.

As a rookie, Payton started seven games and rushed for 679 yards and seven touchdowns. The next season, he had the first of what would be 10 1,000-yard seasons, rushing for 1,390 yards and 13 touchdowns.

In ’77, only his third season in the league, Payton won the first of two MVP awards with the most productive season of his career. He rushed for 1,852 yards and 14 touchdowns, both career highs. His 5.5 yards per carry also was the best of his career.

In the Bears’ Super Bowl season, Payton gained 1,551 yards and had nine rushing touchdowns and also caught 49 passes, with two more for scores. In the Bears’ 46-10 rout of the New England Patriots in the Super Bowl, Payton didn’t score a touchdown, a sore point with him that even caused Ditka to apologize to him afterward for what he said was simply an oversight.

Payton retired after the 1987 season and immediately launched

himself into a successful business career that included part ownership of an

Arena Football league team, several restaurants and a number of other

businesses.

When Payton was inducted into the Hall of Fame, he asked 12-year-old Jarrett to

be the first son to present his father at the ceremonies in Canton, Ohio.

“Not only is he a great athlete, he’s a role model – he’s my role

model,” said Jarrett, now a running back at the University of Miami who

came home last Wednesday to be with his ailing father.

Jarrett Payton read a brief statement at the news conference at Halas Hall today, thanking well-wishers from around the world for their support and encouragement as well as the medical personnel who treated his father since his illness was first diagnosed.

“These last 12 months have been extremely tough for me and

my family,” he said. “We’ve also learned about love and life.”

NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue today called Payton “one of the greatest

players in the history of the sport. . . . Walter was an inspiration in

everything he did. The tremendous grace and dignity he displayed in his final

months reminded us again why ‘Sweetness’ was the perfect nickname for Walter

Payton.”

Mike Singletary, a fearsome middle linebacker who played with Payton from 1981

to ’87, said today he spent the weekend praying and reading scripture with

Payton and saw him again Monday before he died.

“With all the greatest runs, the greatest moves I saw from him, what I experienced was by far the best of Walter Payton that I’ve seen,” Singletary said at Lake Forest. “As a football player, he was really the first running back I ever met that I truly respected in terms of how he prepared. . . . He was the first running back I had ever seen that I thought would be a great defensive player.

“His attitude toward life, you wanted to be around him. If you were down, he would not let you stay down. It was his duty to bring humor and light to any situation. No matter how tough it was, Walter could always make you feel great about playing the game and playing for the Chicago Bears. He was definitely a bright spot wherever darkness appeared.” Research more about this great American Hero an share with your babies. I will be speaking at Dacula High School about the Blacks who served during WWI and how Blacks on the home front lived. November 11, 2018 will be the 100th Anniversary of the end of WWI. I won’t be able to respond to any posts. Make it a champion day!