AUTOMOTIVE HISTORY – DECEMBER 7, 1955 – The Montgomery Bus Boycott The Montgomery Bus Boycott was a civil rights protest during which African Americans refused to ride city buses in Montgomery, Alabama, to protest segregated seating. The boycott took place from December 5, 1955, to December 20, 1956, and is regarded as the first large-scale U.S. demonstration against segregation.Four days before the boycott began, Rosa Parks, an African American woman, was arrested and fined for refusing to yield her bus seat to a white man. The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately ordered Montgomery to integrate its bus system, and one of the leaders of the boycott, a young pastor named Martin Luther King, Jr., emerged as a prominent leader of the American civil rights movement.In 1955, African Americans were still required by a Montgomery, Alabama, city ordinance to sit in the back half of city buses and to yield their seats to white riders if the front half of the bus, reserved for whites, was full.But on December 1, 1955, African American seamstress Rosa Parks was commuting home on Montgomery’s Cleveland Avenue bus from her job at a local department store. She was seated in the front row of the “colored section.”When the white seats filled, the driver, J. Fred Blake, asked Parks and three others to vacate their seats. The other Black riders complied, but Parks refused.She was arrested and fined $10, plus $4 in court fees. This was not Parks’ first encounter with Blake. In 1943, she had paid her fare at the front of a bus he was driving, then exited so she could re-enter through the back door, as required. Blake pulled away before she could re-board the bus.Did you know? Nine months before Rosa Parks’ arrest for refusing to give up her bus seat, 15-year-old Claudette Colvin was arrested in Montgomery for the same act. The city’s Black leaders prepared to protest until it was discovered Colvin was pregnant and deemed an inappropriate symbol for their cause.Although Parks has sometimes been depicted as a woman with no history of civil rights activism at the time of her arrest, she and her husband Raymond were, in fact, active in the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and Parks served as its secretary.Upon her arrest, Parks called E.D. Nixon, a prominent Black leader, who bailed her out of jail and determined she would be an upstanding and sympathetic plaintiff in a legal challenge of the segregation ordinance. African American leaders decided to attack the ordinance using other tactics as well.The Women’s Political Council (WPC), a group of Black women working for civil rights, began circulating flyers calling for a boycott of the bus system on December 5, the day Parks would be tried in municipal court. The boycott was organized by WPC President Jo Ann Robinson.As news of the boycott spread, African American leaders across Montgomery (Alabama’s capital city) began lending their support. Black ministers announced the boycott in church on Sunday, December 4, and the Montgomery Advertiser, a general-interest newspaper, published a front-page article on the planned action.Approximately 40,000 Black bus riders—the majority of the city’s bus riders—boycotted the system the next day, December 5. That afternoon, Black leaders met to form the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA). The group elected Martin Luther King, Jr., the 26-year-old-pastor of Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, as its president, and decided to continue the boycott until the city met its demands.Initially, the demands did not include changing the segregation laws; rather, the group demanded courtesy, the hiring of Black drivers, and a first-come, first-seated policy, with whites entering and filling seats from the front and African Americans from the rear.

Month: December 2021

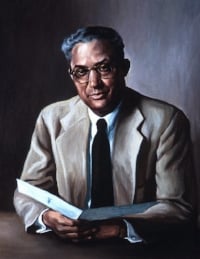

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American dermatologist, medical researcher, and philanthropist.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American dermatologist, medical researcher, and philanthropist. He was a skin specialist and is known for work related to leprosy and syphilis. Lawless was also involved in various charitable causes, including Jewish causes. Related to the latter, he created the Lawless Department of Dermatology in Beilinson Hospital, Tel Aviv, Israel. He received his M.D. degree from Northwestern University Medical School and was a self-made millionaire. In 1954, he won the NAACP Spingarn Medal, presented annually to an African American of distinguished achievement.Today in our History – December 6, 1892 – Theodore Kenneth (T.K.) Lawless (December 6, 1892 – May 1, 1971) died.Lawless was born December 6, 1892, in Thibodeaux, Louisiana to Alfred Lawless Jr., (a Congregational minister, instructor at Straight University, and American Missionary Association district superintendent of churches) and Harriet Dunn Lawless (a school teacher). Soon after his birth, his father moved the family to New Orleans, Louisiana. He earned $1-a-day as a boy in his first job, in a New Orleans market.Lawless attended Straight College (now, Dillard University) in New Orleans for secondary school and went from there to Talladega College in Alabama where he received an A.B. in 1914. He then attended the University of Kansas School of Medicine and Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago, from which he received his MD in 1919 and an MS in 1920.In 1920 he was named a Rosenwald Fellow in Medicine—an award targeting top black medical students—and thereby received $1,200 ($16,000 in current dollar terms). Lawless engaged in graduate studies at the Vanderbilt Clinic of Columbia Medical School and at Harvard Medical School. He held a fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital. He received further postgraduate training outside the United States at the University of Paris’s premier dermatology program at L’Hôpital St. Louis, as well as at the University of Freiburg in Germany, and the University of Vienna in Austria. He noted later that “it was a noteworthy fact in my own life experience that of the twelve letters [of recommendation for study abroad] that I received, eleven were from Jewish physicians.”After graduating in 1924, Lawless returned to Chicago to open his dermatology practice on Chicago’s South Side in a poor, black neighborhood. He became an instructor and research fellow at Northwestern University Medical School the same year and taught there as a professor of dermatology and syphilology until 1941. He helped establish the university’s first medical laboratories and established the first clinical laboratory for dermatology.Lawless performed research on syphilis, leprosy, sporotrichosis, and other skin diseases. In 1936, he helped devise a new treatment for early-stage syphilis (electropyrexia, which artificially raised a patient’s temperature, and then injected the patient with therapeutic drugs). He also developed special treatments for skin damaged by arsenical preparations, which were commonly used during the 1920s against syphilis, and was one of the first doctors to use radium to treat cancer. Between 1921 and 1941 he published ten papers on dermatology, which included studies on warts, sporotrichosis, the use of colloidal mercuric sulphide, arsenicals, the treatment of early syphilis with electrically induced fever, tinea sycosis of the upper lip, tularemia, and congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma.In 1957 Lawless was the first Black member of Chicago’s Board of Health. His professional memberships included the American Medical Association, the National Medical Association, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and in 1935 he became a diplomate of the American Board of Dermatology and Syphilology. He served as an associate examiner in Dermatology for the National Board of Medical Examiners and as a consultant for the United States Chemical Warfare Board.A shrewd investor and businessman, he became a multi-millionaire and had a remarkable business career. Lawless was director of both the Supreme Life Insurance Company and Marina City Bank. He was also a charter member, associate founder, and President of Service Federal Savings and Loan Association in Chicago.Most of his philanthropy involved starting a number of dermatology programs in Israel. Lawless donated $160,000 ($1,500,000 in current dollar terms) in 1957, spearheaded a Chicago fundraising drive for, and established the 35-bed Lawless Department of Dermatology in Beilinson Hospital (later known as the Rabin Medical Center), near Tel Aviv, Israel. He also created the T. K. Lawless Student Summer Camp Program for Talented Children for the scientific training for Israeli children at the Weizmann Institute of Science, in Rehovot, Israel; the Lawless Clinical and Research Laboratory in Dermatology of the Hebrew Medical School in Jerusalem, Israel. He became well acquainted with Chaim Weizmann, Israel’s first President. He thus repaid support received from Jewish doctors in obtaining his appointment to his position at the University of Paris. In 1969 he said: “I’m simply trying to repay a debt of gratitude.” He explained his philanthropy for Israel and Jewish causes by pointing out that when he was a child in New Orleans, a Jewish peddler there was always kind to his family, a Jewish professor (Maurice Lenz) had helped him at Columbia University, and he also recalled another Jewish friend. In the 1960s, he worked for the Israel Bonds drive and purchased a large number of the bonds. In December 1967, on his fifth trip to Israel, he made a donation establishing a fund to repair and restore ancient Biblical archeological discoveries at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, his fifth project in Israel.Lawless also supported Roosevelt University’s Chemical Laboratory and Lecture Auditorium, in Chicago, and Lawless Memorial Chapel at Dillard University, in New Orleans. In 1959, he was elected President of the Dillard University Board of Trustees. In 1967, the ground was first broken for the Theodore K. Lawless Gardens, in his honor and of which he was a principal, a 13-acre 514-unit middle-income housing project at 35th and Rhodes Avenue on Chicago’s South Side. He also served as Chairman of the Board of Trustees of Talladega College, Chairman of the American Missionary Association and Division of Higher Education of the Congregational and Christian Church, and Director of Youth Services of the B’nai B’rith Foundation.He died in Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago at age 78 on May 1, 1971. Lawless left $150,000 ($1,000,000 in current dollar terms) of his $1.25 million ($8,000,000 in current dollar terms) estate to the American Committee of the Weizmann Institute, a New York research institution.Lawless won the Harmon Award in Science for outstanding work in medicine in 1929.In 1954, Lawless won and became the 39th recipient of the NAACP Spingarn Medal, presented annually to a Black American of distinguished achievement, for his contributions as a “physician, educator and philanthropist”. In 1963 he received Roosevelt University’s second annual Daniel H. Burnham Award. Phi Beta Kappa honored him with its Distinguished Service Award in 1966 for “acts of charity and medical service”. In 1967 he received the University of Kansas Distinguished Service Citation and the City of Hope Golden Torch Award. In 1970 he received the Beatrice Caffrey Youth Service Merit Award.He also received the Citation of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, and the Greater Chicago Churchman Layman-of-the-Year Citation.Lawless received honorary degrees from Talldega (D.Sc.), Howard University (D.Sc.), Bethune-Cookman College (LL.D.), the University of Illinois (LL.D.), and Virginia State University (LL.D.).He was also honored by having a county park in Cass County near Vandalia, Michigan named after him (Dr. T.K. Lawless Park). The park features a range of outdoor activities, including a 10-mile mountain bike trail, shelters, softball fields, and soccer fields.A portrait of Lawless painted by Betsy Graves Reyneau is in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution at the National Portrait Gallery. It was originally collected by the Harmon Foundation as part of a project to document noteworthy African Americans. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

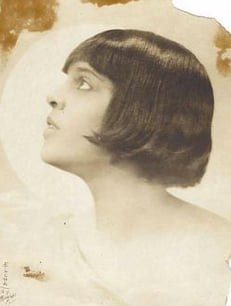

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American dancer, teacher, and boxer.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American dancer, teacher, and boxer.Today in our History – December 5, 1893 – Emma Chambers Maitland (December 5, 1893 – March 1975) was born.Jane Chambers was born near Richmond, Virginia, the daughter of Wyatt Chambers and Cora Chambers. Her parents were sharecroppers, and she had seven brothers. She was educated at a convent school at Rock Castle, Virginia, and qualified as a teacher. She changed her first name when she moved to Washington, D.C. as a young woman. Emma Maitland was a woman of many talents. She was dancer and actress but it was boxing that made her name well-known. Maitland was successful as a fighter, she earned hundreds of dollars per fight. She was later earned the title lightweight boxing champion of the worldMaitland was born in Virginia in 1893.Her parents worked as tobacco farmers. After completing her primary education, she took and passed the exam to become a teacher.Within a few years of passing the exam, Maitland relocated to Washington, D.C., where she later met her husband who was attending Howard University. The couple had a daughter, but within a year of being married, tragedy struck and her husband, Clarence Maitland, died from tuberculosis.Being left to raise her daughter alone, Maitland decided to pursue a career as a dancer. She left her child with her parents and headed to Paris to pursue a career. She traveled throughout Europe performing with a dance troupe and ended up back in the United States. She later performed in the musical Shuffle Along and later appeared in the theater production Harlem at the Apollo Theater.Chambers was a teacher as a young woman in Virginia. As a widow with a young daughter to support, Maitland moved to Paris. She danced at the Moulin Rouge, modeled for artists, and did a boxing act with another American performer, Aurelia Wheedlin (or Wheeldin). She became serious about boxing, trained with American boxer Jack Taylor, and toured with Wheedlin in Europe, billed as the world’s lightweight female boxing champion. She also boxed in Canada, Cuba and Mexico. Maitland moved back to the United States in 1926, lived in New York City, and continued performing as a “boxeuse”. She appeared (often with Wheedlin) in clubs, on vaudeville and on the New York stage in black revues, including Messin’ Around (1929), Change Your Luck (1930), and Fast and Furious (1931). She worked as a bodyguard and taught dance and gymnastics. In her later years she moved to Martha’s Vineyard. By 1927, Maitland was training as a boxer. She appeared in a boxing skit in Paris, where she and another black boxer Aurelia Wheeldin boxed three rounds. After hanging up her boxing gloves, Maitland taught dance and gymnastics in New York. Emma Maitland married a Howard University medical student, Clarence Maitland. They had a daughter together in 1917. Clarence Maitland died from tuberculosis within a year of their wedding. She died in early 1975, aged 82. Maitland donated her papers and souvenirs to the Schomburg Collection at the New York Public Library, in 1943. In 2015, Maitland’s former home in Oak Bluffs became a stop on the African American Heritage Trail of Martha’s Vineyard. In 2020, she was the subject of an exhibit at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make It A Champion Day!

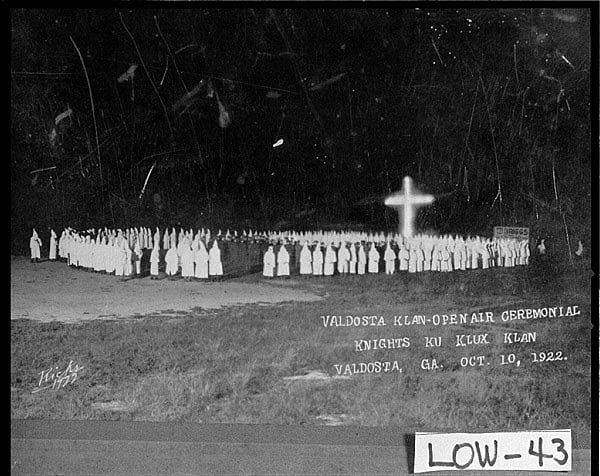

GM –FBF – Today’s American Champion event was In politics, for example, Fulton County Solicitor General John M. Boykin and Fulton Superior Court Judge Gus H.

GM –FBF – Today’s American Champion event was In politics, for example, Fulton County Solicitor General John M. Boykin and Fulton Superior Court Judge Gus H. Howard were both Klansmen. The Klan’s chief lawyer, Paul S. Etheridge, himself sat on the Fulton County Board of Commissioners of Roads and Revenues. Klansman Walter A. Sims was elected mayor of Atlanta in 1922, in a campaign centered on the prohibition of interracial worship. And after being tagged as insufficiently supportive of Klan efforts, in 1922 Georgia’s Governor Thomas Hardwick was voted out of office and replaced with ardent Klan supporter Clifford Walker.Today in our History – December 4, 1915 – The KKK receives charter to operate in Georgia.It is in cultural pursuits, though, that we see the full extent to which the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s had been absorbed into the ordinary, everyday white supremacism of life in Atlanta. Whether a member or not, you could stop at newsstands across the city to pick up a copy of the Klan’s newspaper, Searchlight. Financed by Tyler and edited by J. O. Wood (who was also a member of the state legislature), the weekly focused its reporting on the ostensible good deeds and charitable works of the Klan, mixed with local news and comment. More than sixty thousand people purportedly read Searchlight each week, and the publication carried advertisements from a wide cross-section of local businesses, including Coca-Cola.Within the pages of Searchlight, we find the vibrant cultural life of the ordinary white supremacist. For those seeking an evening’s entertainment, the citizens of Atlanta could attend a Klan-organized screening of the smash hit Birth of a Nation or one of the increasing number of the Klan’s own feature films. They could turn on the radio to listen to Klansman Fiddlin’ John Carson, or purchase one of the OKeh recordings of his music – recordings which helped create country music as a commercial genre.3 Maybe they would be lucky enough to catch the traveling stage show, The Awakening, which mingled the plot of Birth of a Nation with musical numbers and cabaret-style showgirls. Since the show relied on local amateur theater to fill its ranks as it moved from town to town, many Atlantans also appeared in the production.If readers turned instead to the sports pages of the Atlanta Constitution (where Edward Young Clarke’s brother worked as managing editor), they could find box scores for the Atlanta Klan’s baseball team. In 1924, the Klan played in the amateur Dixie League against teams including their neighbors from the Peachtree Road Presbyterian Church, Georgia West Point, and the Georgia Railroad and Power Company. In a reflection of the Klan’s immersion in everyday life, the rivalry between the Klan team and the Georgia Tech Rehabs team for the league pennant (eventually won by the Klan) garnered far more press attention than the Klan’s nonleague games against more surprising opponents, including the Catholic Knights of Columbus.4 Clearly, membership in the Invisible Empire was no bar to participation in community life.This is not to say the Klan was without controversy. Atlanta was also where the Klan’s dirty laundry was aired – where Clarke and Tyler were arrested on morals charges; where the Klan’s leading religious official, known as the “Kludd,” Caleb Ridley was arrested for drunk driving; and where the Klan’s press chief, Philip Fox, shot his rival, William S. Coburn.5 And gradually the Klan’s presence in the city lessened.As Hiram Evans wrested control of the Klan from Imperial Wizard Simmons and focused increasingly on politics, he would make Washington, DC, the new Klan headquarters. Ultimately, the Klan’s Imperial Palace would be sold off to an insurance company, who then sold the property to the Catholic Church. It is now the site of the Cathedral of Christ the King.Yet the Klan’s legacy lingers on in Atlanta. While seemingly emboldened in recent months, and the subject of rising visibility, contemporary white supremacists did not appear from nowhere. The Association of Georgia Klans, headed by Atlanta obstetrician Samuel Green, was established with another cross burning at Stone Mountain in 1945. As Green’s organization faded, it was supplanted by the U.S. Klans in the 1950s. Even as the city became an epicenter for the Civil Rights Movement, a summit just south of Atlanta saw the creation of the United Klans of America. At a 1962 Fourth of July protest at Stone Mountain, robed Klansmen mingled with other segregationists and neo-fascists from the area. Over the past decades, the Atlanta metro region has continued to provide a home for branches of the Loyal White Knights of the Klan, the Aryan Nations, and the many others who may pay no formal dues but nonetheless share white supremacist views. Just as with the men and women of the Klan in the 1920s, these men and women today are not strange, otherworldly creatures, incapable of ordinary human interests, but rather all too familiar. Examining the Klan’s past cultural endeavors reminds us of the insidious and pervasive presence white supremacism has held in everyday life. Such examinations are critical. Until we understand the deep-rooted history of that presence, we will remain unable to truly reckon with the “normal” white supremacists of today.Research more about this great American tritest group and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

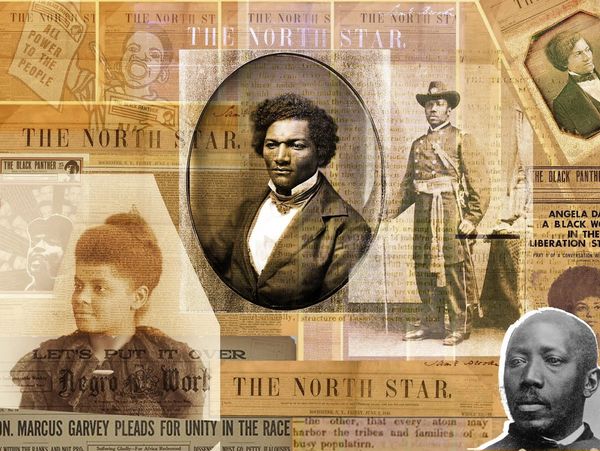

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was company was ahead of its time.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was company was ahead of its time. The North Star was a nineteenth-century anti-slavery newspaper published from the Talman Building in Rochester, New York, by abolitionist Frederick Douglass. The paper commenced publication on December 3, 1847, and ceased as The North Star in June 1851, when it merged with Gerrit Smith’s Liberty Party Paper (based in Syracuse, New York) to form Frederick Douglass’ Paper. At the time of the Civil War, it was Douglass’ Monthly. The North Star’s slogan was: “Right is of no Sex—Truth is of no Color—God is the Father of us all, and all we are Brethren.”Today In Our History – December 3, 1847 – The North Star Newspaper was born.In 1846, Frederick Douglass was first inspired to publish The North Star after subscribing to The Liberator, a weekly newspaper published by William Lloyd Garrison. The Liberator was a newspaper established by Garrison and his supporters founded upon moral principles. The North Star title was a reference to the directions given to runaway slaves trying to reach the Northern states and Canada: “Follow the North Star.” Figuratively, Canada was also “the north star.”Like The Liberator, The North Star published weekly and was four pages long. It sold by subscription of $2 per year to more than 4,000 readers in the United States, Europe, and the Caribbean. The first of its four pages focused on current events concerning abolitionist issues.The Garrisonian Liberator was founded upon the notion that the Constitution was fundamentally pro-slavery and that the Union ought to be dissolved. Douglass disagreed but supported the nonviolent approach to the emancipation of slaves by education and moral suasion.Under the guidance of the abolitionist society, Douglass became well acquainted with the pursuit of the emancipation of slaves through a New England religious perspective. Garrison had earlier convinced the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society to hire Douglass as an agent, touring with Garrison and telling audiences about his experiences as a slave. Douglass worked with another abolitionist, Martin R. Delany, who traveled to lecture, report, and generate subscriptions to The North Star.attended the National Convention of Colored Citizens, an antislavery convention in Buffalo, New York, in August 1843. One of the many speakers present at the convention was Henry Highland Garnet. Formerly a slave in Maryland, Garnet was a Presbyterian minister who supported violent action against slaveholders. Garnet’s demands of independent action addressed to the American slaves remained one of the leading issues of change for Douglass.During a nineteen-month stay in Britain and Ireland, several of Douglass’ supporters bought his freedom and assisted with the purchase of a printing press. With this assistance, Douglass was determined to begin an African-American newspaper that would engage the anti-slavery movement politically.On his return to the United States in March 1847, Douglass shared his ideas of The North Star with his mentors. Ignoring the advice of the American Anti-Slavery Society, Douglass moved to Rochester, New York to publish the first edition. When questioned on his decision to create The North Star, Douglass is said to have responded,I still see before me a life of toil and trials…, but, justice must be done, the truth must be told…I will not be silent.In covering politics in Europe, literature, slavery in the United States, and culture generally in both The North Star and Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Douglass achieved unconstrained independence to write freely on topics from the California Gold Rush to Uncle Tom’s Cabin to Charles Dickens’s Bleak House.Besides Garnet, other Oneida Institute alumni that collaborated with The North Star were Samuel Ringgold Ward and Jermain Wesley Loguen.Douglass was assisted by philanthropist Gerrit Smith. Smith later merged his own anti-slavery paper with The North Star to create Frederick Douglass’ Paper. Research more about this great American Champion and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American politician from Connecticut.

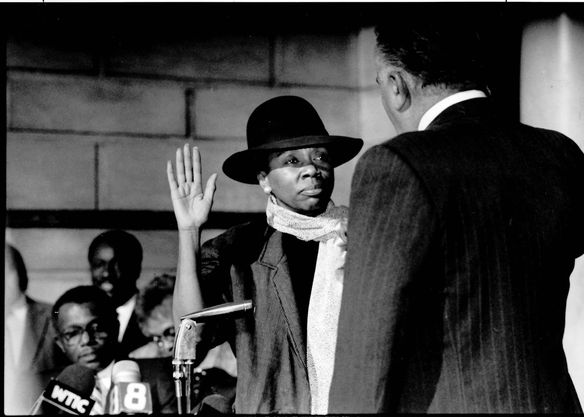

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American politician from Connecticut. She was notable as the first African American woman to be elected mayor of a major New England city – Hartford, Connecticut – in 1987. She served three terms before being defeated in 1993. She served as a member of the Connecticut House of Representatives from 1980 until 1987. She was known for her distinctive broad-rimmed hats.Today in our History – December 1, 1987 – Carrie Saxon Perry (August 30, 1931 – November 22, 2018) was elected Mayor of Hartford, Connecticut.Perry was born on August 30, 1931, in Hartford to David Saxon and Mabel Lee. She was primarily raised by her grandmother after her father left the family when she was only six months old.She graduated from Howard University with a degree in economics and attended Howard University School of Law for two years before leaving school to marry James Perry, Jr. After leaving law school, she worked with a number of community organizations and help establish boards for organizations such as Planned Parenthood. She also worked for the state welfare agency.Her first run for state representative ended in defeat in 1976. She was elected in 1980 and served until her election as mayor. She was selected as an assistant majority leader, chair of the bonding subcommittee, and a committee member for education, finance, and housing.She became known for donning unique hats, of which she owned about two dozen. She said she started the habit because didn’t have time to take care of her hair.Perry was elected the mayor of Hartford at the age of 56.In 1987, Mayor Thirman L. Milner, the city’s first African American mayor, announced that he would not seek re-election to city hall. Perry entered the race and won the endorsement of the local Democratic Party. In the general election, she defeated Republican Philip Steele with 58 percent of the vote.She was credited for helping reduce racial tension in the city; notably, she visited black neighborhoods after the Rodney King verdict, which was credited with preventing rioting in Hartford as had happened in other large cities.She championed LGBT rights in Hartford during her mayorship, introducing legislation to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation in Hartford schools, 5 years before such legislation was adopted in Connecticut.She also focused on reducing burgeoning gang activity and drug trafficking, which was on the rise at the time. The position in Hartford is considered largely ceremonial and paid a stipend of $17,500.After three terms as mayor, she was defeated by first-time Democratic challenger Michael Peters, a city firefighter. He had run on a campaign capitalizing on Hartford’s declining economy and a sense that street crime was on the rise.Perry married James Perry, Jr. from whom she was divorced. She had a son, four grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.Perry died on November 22, 2018, at the age of 87. However, her death remained unreported until November 2019.Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!