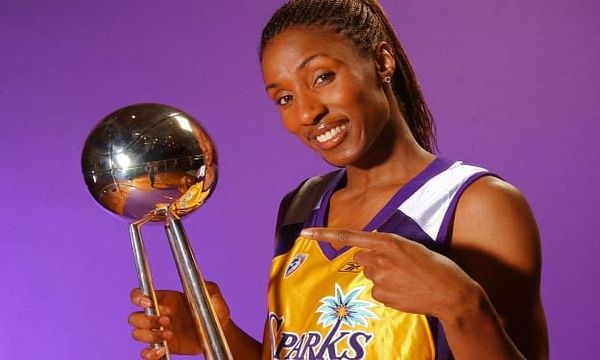

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American former professional basketball player. She is currently the head coach for Triplets in the BIG3 professional basketball league, as well as a studio analyst for Orlando Magic broadcasts on Fox Sports Florida. She played in the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA). She is a three-time WNBA MVP and a four-time Olympic gold medal winner. The number-seven pick in the 1997 inaugural WNBA draft, she followed her career at the University of Southern California with eight WNBA All-Star selections and two WNBA championships over the course of eleven seasons with the Los Angeles Sparks, before retiring in 2009.She was the first player to dunk in a WNBA game. In 2011, she was voted in by fans as one of the Top 15 players in WNBA history. In 2015, she was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. She was also inducted into the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame in 2015.Today in our History – July 7, 1972 – Lisa Deshaun Leslie was born.Lisa Deshaun Leslie is an American former professional basketball player who played for the Los Angeles Sparks in the Women’s Basketball Association (WNBA) for her twelve-year career from 1997 to 2009. She is a two-time WNBA champion, three-time WNBA MVP, and a four-time Olympic gold medal winner. Leslie was the first player to dunk in a WNBA game and was considered a pioneer and cornerstone of the league during her NBA career.Lisa Leslie was born on July 7, 1972, in Gardena, California, to Christine Lauren Leslie and Walter Leslie, a semi-professional basketball player. Christine Leslie started her own trucking business to support her three children after her husband left the family. Leslie has two sisters, Dionne and Tiffany, and a brother, Elgin. By the time Leslie was in middle school, she had grown to over 6′1″. In the eighth grade, she transferred to a junior high school without a girls’ basketball team and joined a boys’ basketball team. Leslie entered Morningside High School in Inglewood, California, in 1986 and while there led the girls’ basketball team to two state championships.After high school, Leslie entered the University of Southern California (USC), where she played for the Trojans’ women’s basketball team from 1990 to 1994. During her time with the Trojans, she played 120 college games, averaging 20.1 points per game, making 53.4 percent of her shots, and 69.8 percent of her free throws.She set the PAC-10 Conference records for scoring, rebounding, and blocked shots accumulating 2,414 points, 1,214 boards, and 321 blocked shots. She also holds the USC single-season record for blocked shots (95). Leslie helped the team win one PAC-10 conference championship in 1994 and earn four NCAA tournament appearances. She was All-PAC 10 for four years and also earned All-American Honors. Leslie was also named national player of the year in 1994. She graduated from USC with a bachelor’s degree in communications in 1994.After USC, Leslie was drafted by the Los Angeles Sparks in the 1997 WNBA draft. During her twelve-year career with the Sparks, she led the team to two WNBA championships in 2001 and 2002. She was WNBA finals MVP in both championships. Other accomplishments included being named WNBA MVP three times (2001, 2004, 2006); she was also an eight-time All-Star (1999-2003, 2005, 2006, 2009). She was a two-time WNBA Defense Player of the Year (2004, 2008). On July 30, 2002, she made WNBA history when she became the first woman to dunk in a WNBA game. Leslie also won gold medals as a member of the USA Women’s Basketball team in 1996 Atlanta (Georgia) Olympic Games, 2000 Sydney (Australia) Olympic Games, 2004 Athens (Greece) Olympic Games, and 2008 Beijing (China) Olympic Games.Leslie retired at the end of the 2009 WNBA season. She finished her career holding the league records for points (2,263), rebounds (3,307), and PRA (Points, Rebounds, and Assists) (10,444). In 2011, Leslie was voted by fans as one of the top fifteen players in WNBA history. In 2015, she was elected to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.In 2006, Leslie married Michael Lockwood. The couple has two children, Lauren Jolie Lockwood, born on June 15, 2007, and Michael Joseph Lockwood II, born on April 16, 2010. In 2009, Leslie earned a Master’s of Business Administration (MBA) degree from the University of Phoenix in Arizona. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

Category: Brandon Hardison

AUTOMOTIVE HISTORY – JULY 6, 1851 – Inventor Thomas Davenport dies

AUTOMOTIVE HISTORY – JULY 6, 1851 – Inventor Thomas Davenport dies Thomas Davenport (9 July 1802 – 6 July 1851) was a Vermont blacksmith who constructed the first American DC electric motor in 1834.Davenport was born in Williamstown, Vermont. He lived in Forest Dale, a village near the town of Brandon.As early as 1834, he developed a battery-powered electric motor. He used it to operate a small model car on a short section of track, paving the way for the later electrification of streetcars.Davenport’s 1833 visit to the Penfield and Taft ironworks at Crown Point, New York, where an electromagnet was operating, based on the design of Joseph Henry, was an impetus for his electromagnetic undertakings. Davenport bought an electromagnet from the Crown Point factory and took it apart to see how it worked. Then he forged a better iron core and redid the wiring, using silk from his wife’s wedding gown.With his wife Emily and colleague Orange Smalley, Davenport received the first American patent on an electric machine in 1837, U. S. Patent No. 132. He used his electric motor in 1840 to print The Electro-Magnetic and Mechanics Intelligencer – the first newspaper printed using electricity.In 1849, Charles Grafton Page, the Washington scientist, and inventor commenced a project to build an electromagnetically powered locomotive, with substantial funds appropriated by the US Senate. Davenport challenged the expenditure of public funds, arguing for the motors he had already invented. In 1851, Page’s full-sized electromagnetically operated locomotive was put to a calamity-laden test on the rail line between Washington and Baltimore.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a abolitionist, conductor on the Underground Railroad and co-founder of the New England Freedom Association, and politician, serving one term as a Massachusetts state legislator.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a abolitionist, conductor on the Underground Railroad and co-founder of the New England Freedom Association, and politician, serving one term as a Massachusetts state legislator. He worked as a caterer in Boston, starting his own business at the age of 36.Today in our History – July 5, 1879 – Joshua Bowen Smith (1813–1879) dies.Joshua Bowen Smith was born in 1813 in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, to a mother of mixed African-American/Native American ancestry and a British father. He grew up in Philadelphia, where he was educated on a scholarship from a Quaker philanthropist.As a young man, in 1836 Smith moved to Boston, Massachusetts, where he became the headwaiter at the dining room of the Mount Washington House hotel. There he befriended United States Senator Charles Sumner and John J. Fatal, both influential abolitionists. For several years he worked for the catering business of H. R. Thacker before starting his own business at the age of 36. Over the next 25 years, Smith made a small fortune catering commencement dinners for Harvard College, as well as various events for the city, local organizations, and the Union army during the Civil War years. Through his work he befriended many other local abolitionists, including William Lloyd Garrison, George Luther Stearns, Robert Gould Shaw, and Theodore Parker. Smith became involved in the Underground Railroad and was a member of the Boston Vigilance Committee, which worked to aid refugee slaves. He harbored refugee slaves in his home in Cambridge, employed them in his business as cooks and waiters, and often gave them money out of his own pocket, as well as weapons and supplies if they were traveling on to Canada to ensure their freedom.He was a co-founder of the New England Freedom Association, a fugitive slave assistance group founded by African Americans. Smith, a Baptist, believed that the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was an “un-Christian” law, and that violence in defense against slavery was morally justified. He once displayed a dagger and a revolver from the pulpit during a speech. Smith’s catering business suffered a fatal blow in 1861 when Massachusetts Governor John Albion Andrew refused to reimburse him for services provided to the 12th Massachusetts Regiment over a 93-day period. Andrew claimed he could not pay the bill because the legislature had not approved the funds, yet he paid all the other caterers who were also owed money. Smith sued the state in 1879 and received some compensation, but not enough even to recoup his legal expenses. He spent the rest of his life in debt. In 1865, Smith was instrumental in persuading state officials to commission a memorial to Robert Gould Shaw, who commanded the African-American 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, which had distinguished itself during the war. He worked with Governor Andrews, Senator Charles Sumner, and other supporters of the proposal.The state ultimately commissioned Augustus Saint-Gaudens for the work, and he created a bronze relief sculpture depicting Colonel Shaw and members of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment as they marched through Boston to depart for the war. It was unveiled and dedicated on May 31, 1897. In October 1867 Smith became the first African-American member of the Saint Andrew’s Lodge of Freemasons of Massachusetts, and served as junior warden of the Adelphi Lodge in South Boston. From 1873 to 1874, he represented Cambridge for one term in the Massachusetts state legislature, where he served as chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations. He advised Senator Charles Sumner on his draft of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, and helped persuade the state legislature to rescind its censure of Sumner. At the senator’s death, Sumner bequeathed to Smith a painting titled The Miracle of the Slave. He had purchased it in a Montpellier art gallery, and it was likely a copy of the eponymous painting by Italian Tintoretto. Smith died in Boston on July 5, 1879, after a prolonged illness. He was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge. Smith’s former home at 79 Norfolk Street in Cambridge is marked with a plaque installed in 1994 by the Cambridge African American History Project. Smith bought the house in 1852 and lived there with his wife, Emeline, until his death. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

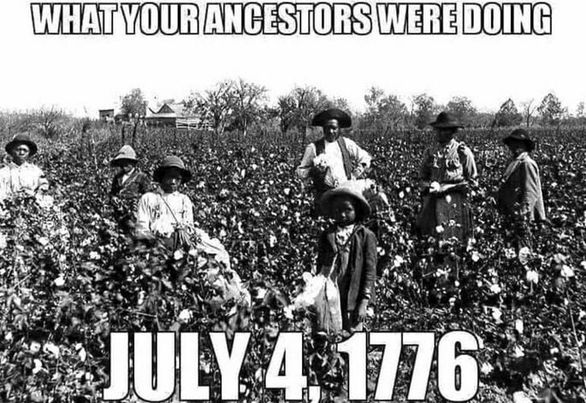

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event America has been working to fully live up to the ideals laid out in the Declaration of Independence ever since the document was printed on July 4, 1776.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event America has been working to fully live up to the ideals laid out in the Declaration of Independence ever since the document was printed on July 4, 1776. So while the U.S. tends to go all out celebrating freedom on the Fourth of July, alternate independence commemorations held a day later often draw attention to a different side of that story, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”Today in our History – July 4, 1801 – Continental Army veteran and black luminary Lemuel Haynes spoke of American freedom alongside American slavery.Since the very beginning, black Americans have used the national celebration of the country’s independence on July 4 to remind white Americans that they too deserved freedom and that their lives also mattered. Celebrating this tradition of black protest is essential today as the nation grapples with policing, violence and racism in the wake of George Floyd’s death.The signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776 was itself an act of protest. The famed signatories — Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams and the members of the Second Continental Congress — understood this as they broke from British tyranny and launched a new nation.As the ink dried on the Declaration of Independence, Adams imagined the signing would “be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival … [and] Day of Deliverance … with Pomp and Parade.” He guessed right. Since then, Americans have assembled on the holiday to reflect on what it means to be American and to commend the signatories who criticized poor governance and chose revolutionary change rather than complacency.Black Americans have always populated the celebrations, using these moments to reimagine America as a better nation cleansed of slavery and racism. On July 4, 1801, Continental Army veteran and black luminary Lemuel Haynes spoke of American freedom alongside American slavery. From the pulpit of his Vermont church, he lauded the “generous warriors” of the Revolutionary War yet also observed how black Americans suffered after having been “subjected to slavery, by cruel white oppressors.”In 1827, black New Yorkers celebrated with renewed enthusiasm, as the state had abolished slavery on the holiday. In Brooklyn, in Manhattan and in Albany, newly freed celebrants took to the streets proclaiming freedom. From that day forward, as historian Shane White discovered, black Americans began to see the holiday as a political moment to show their fitness for citizenship.July Fourth also became the ideal moment to reshape the nation. Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, black Americans sparsely celebrated the day, as they were routinely shunned or attacked in public, but by the late 1840s, black abolitionists had developed genius techniques to lampoon and lament American commitments to freedom amid rampant unfreedoms and inequalities. This included celebrating independence. They understood the day of freedom festivals served as the best moment to challenge Americans, especially white Americans, to reflect on subjects too often ignored: slavery and racism.Black abolitionists organized celebrations, mixing commonplace traditions, such as reading the Declaration of Independence to venerate the founders, with demonstrations critical of slavery and racism. They read accounts of injustices and poems. Sometimes they would even burn effigies of proslavery politicians.Frederick Douglass joined this movement, using his newspaper, The North Star, to draw attention to these celebrations. In 1852, he famously commemorated the signing of the Declaration of Independence yet mixed cutting irony with patriotic sentiments in the hope of evoking change. “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?,” Douglass asked the packed hall of white abolitionists. “I answer,” he continued: It is “a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless.”Although Douglass offered an incendiary assessment of America, before he stepped off the stage, he embraced the country as a patriot. He closed his oration venerating the Constitution as a “GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT” and pushed for reforms to end bondage and inequality. To him, July Fourth was not merely parades, barbecues or fireworks. He feted the country he cherished while rendering plainly the injustices white America refused to see. Throughout the 1850s, black and white abolitionists assembled each July Fourth, hoping to use their celebrations to challenge Americans to change. On July 4, 1854, the onetime enslaved New Yorker Sojourner Truth demanded white audiences reflect, a theme driving black abolitionist celebrations. She decried the ongoing injustices black Americans faced and warned a crowd of white and black celebrants that “God would yet execute his judgements [sic] upon white people for their oppression and cruelty.”While the abolitionist calendar included celebrations of Emancipation Day and August First to mark major victories in the abolitionist movement, the famed abolitionist William Wells Brown saw the abolitionist festivals of American independence to be “the most important meetings held during the year.” Even if the country had a long way to go before it mirrored the nation they yearned to live in, Douglass, Truth and Brown believed July Fourth offered a perfect opportunity to acknowledge the flaws that needed to be eradicated.Like the Declaration’s signatories, abolitionists appreciated that protest can be a patriotic act and part of meaningful change. They remained on the fringe of the political scene, yet their advocacy compelled many white Americans to ponder the hypocrisy of slavery in a nation committed to freedom and its future. During the Civil War, abolitionist celebrations intensified. Confederates fought to make slavery a permanent fixture in North America, so Douglass implored Abraham Lincoln to embrace abolition as part of the Union cause. As U.S. flags fluttered around the legendary orator during an 1862 festival, Douglass spoke of the meaning of July Fourth, dedicating it to the “cause of Emancipation.” Just as he had a decade before, Douglass wanted to mend the nation and guarantee it would thrive for generations; ending slavery was the only way to accomplish both.Thanks in part to abolitionists’ protests against slavery and racial injustice, the 1865 July Fourth celebrations were the most dramatic in history. By the summer of 1865, the Union army had defeated Confederates, and nearly four million enslaved Americans walked free. Hungry to rebuild a just America, black and white abolitionists cheered on the nation, as many defeated white Southerners refused to participate in the festivities.In the nation’s capital, black Americans paraded through the streets and exulted America. Formerly enslaved Americans reflected on what had been achieved and hoped for a brighter tomorrow. Louis Hughes captured the significance. Hughes, his wife and his child protested bondage by fleeing their enslavers during the war. In the summer of 1865, they trudged toward freedom in Union-occupied Tennessee. “It was appropriately the 4th of July when we arrived,” Hughes reflected, “and, aside from the citizens of Memphis, hundreds of colored refugees thronged the streets. Everywhere you looked you could see soldiers. Such a day I don’t believe Memphis will ever see again.” Freedpeople and soldiers unleashed victorious huzzahs. Hughes and his family merged their rejoicing with the July Fourth elation. “Freedom, that we had so long looked for,” he said, “had come at last.”Black Americans from Haynes to Truth to Hughes knew the hypocrisy embedded within the nation’s celebration of freedom and justice. But they, like those celebrated signatories of the Declaration, grasped the country’s potential for progress and that only dedicated, persistent protests and activism could deliver the nation from the ever-present tyranny of slavery and racism. Today, as protesters again assemble to challenge injustices, it is again time to imagine how we can better the country. Research more on those American Champions who have spoken on this day, remember the past and speaking of the changes made since the framers signed this GREAT EXPERIMENT into this ever evolving country 245 years ago, and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’ American Champion was a South Carolina African-American Human Rights leader, businessman, local preacher, and community organizer.

GM – FBF – Today’ American Champion was a South Carolina African-American Human Rights leader, businessman, local preacher, and community organizer. He was the founder and leader of many organizations and institutions which helped improved the political, educational, housing, health and economic conditions of Sea Island residents.On this day in our History – July 3, 1972 – Esau Jenkins (July 3, 1910 – October 30, 1972) was born.Jenkins grew up during the times of segregation, when educational opportunities were not readily available to him. However, he knew the importance of education and was determined that his children and those of others would not be denied. In the 1940s, Esau and his wife Janie used their money from farming and selling produce to purchase several buses. These buses were used to transport their own children and others on the Sea Islands to school in Charleston and thus further their education. In 1951, he was instrumental in the establishment of Haut Gap High School on John’s Island, so all children on the island would have the educational opportunity to better themselves. Today, Haut Gap is an advance studies magnet middle school.Jenkins’ buses also transported workers to jobs in the Charleston area. During the bus rides, Jenkins and his wife would teach their adult passengers the information needed to pass the literacy exam, so they could become registered voters. Jenkins realized the need for a systemic approach to adult education. At the invitation of Septima Clark, he traveled to Highlander Folk Center to meet with Myles Horton to discuss the need for adult education and citizen classes on the Sea Islands. The first citizenship school was established on John’s Island at the Progressive Club (listed in 2007 on the National Register of Historic Places ). The Progressive Club was a co-op started in 1948 by Jenkins and other families on John’s Island. Notable individuals participated in workshops including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and many others. The co-op housed a community grocery store, gas station, recreation area, sleeping rooms, classroom space and allowed residents to trade goods and services to help each other in times of need. The school was so effective that it served as the model for other citizenship schools established throughout the South to teach adult education, basic literacy and political education classes and workshops, resulting in thousands of citizens becoming registered voters.Jenkins founded the Citizens Committee of Charleston in 1959 and the C.O. Federal Credit Union in 1966. This credit union helped to further the economic advancement of the community. Residents were able to secure low-interest loans to purchase homes, businesses, vehicles and even send their children to college.Jenkins was also one of the founders of Rural Mission, Inc. This initiative provided services for migrant and seasonal farm workers on the Sea Islands. In or about 1970, Rural Mission, Inc. received $96,000.00 through the Office of Economic Opportunity with the assistance of Senator Ernest F. Hollings to start a health clinic at Bethlehem United Methodist Church to serve the five sea islands of Charleston County: Johns Island, James Island, Wadmalaw Island, Edisto Island, and Yonges Island. In February 1972, the health clinic became a separate incorporated entity and was known as Sea Island Comprehensive Health Care Corporation, a comprehensive health care center for the Sea Island residents.Jenkins and his wife owned and operated a fruit and vegetable stand, a fleet of buses, a motel and restaurant in Charleston, SC and also on Atlantic Beach, SC.Mr. Jenkins was known for his iconic 1966 Volkswagen deluxe station wagon that he used for his work in the community and throughout the South. Printed on the back panels of the vehicle was Jenkins’ motto: “Love is Progress, Hate is Expensive.” In 2014, the Jenkins family donated the back panels of the vehicle to the new Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture to become a part of one of the permanent exhibits entitled “Defining Freedom, Defending Freedom: The Era of Segregation”.The Smithsonian, the Jenkins family, and the Preservation Society of Charleston hosted the bus artifacts send off to the Smithsonian on June 1, 2014. This event was included in the Piccolo Spoleto Festival and several hundred attended. All local Charleston news outlets covered the story via interviews and articles about the event.The Historic Vehicle Association and the College of Charleston’s Historic Preservation and Community Planning BA Program were instrumental in preserving the Volkswagen bus, and in September 2019, the bus was the 26th vehicle added to the National Historic Vehicle Register.Jenkins died on October 30, 1972. He has received many posthumous awards, including having a bridge, street, and health clinic named in his memory. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

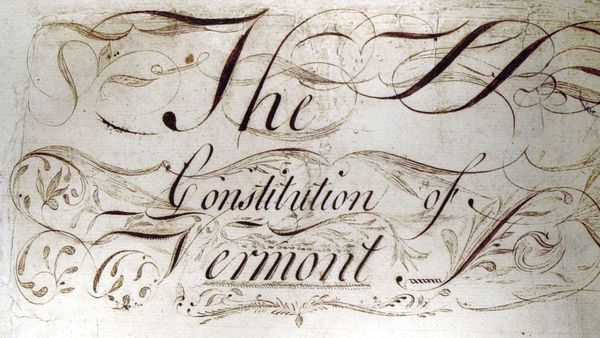

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event is the first sign that America will end slavery as an estimated number of enslaved persons at 25 in 1770 slavery was banned outright upon the founding of Vermont in July 1777, and by a further provision in its Constitution, existing male slaves become free at the age of 21 and females at the age of 18.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event is the first sign that America will end slavery as an estimated number of enslaved persons at 25 in 1770 slavery was banned outright upon the founding of Vermont in July 1777, and by a further provision in its Constitution, existing male slaves become free at the age of 21 and females at the age of 18. Not only did Vermont’s legislature agree to abolish slavery entirely, but it also moved to provide full voting rights for African American males. According to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture, “Vermont’s July 1777 declaration was not entirely altruistic either. While it did set an independent tone from the 13 colonies, the declaration’s wording was vague enough to let Vermont’s already-established slavery practices continue.”Today in our History – July 2, 1777 – The great state of Vermont steps forward and abolishes slavery.Vermont became the first colony to abolish slavery when it ratified its first constitution and became a sovereign country, a status it maintained until its admittance to the union in 1791 as the 14th state in the United States. Read the selection from Chapter I of Vermont’s 1777 constitution which abolishes slavery below:no male person, born in this country, or brought from oversea, ought to be holden by law, to serve any person, as a servant, slave or apprentice, after he arrives at the age of twenty-one Years, nor female, in like manner, after she arrives at the age of eighteen years unless they are bound by their own consent, after they arrive to such age, or bound by law, for the payment of debts, damages, fines, costs, or the like.Despite the de jure abolition of slavery for men over the age of 21 and women over the age of 18, the claim that Vermont completely abolished slavery in 1777 has been subject to dispute.Harvey Amani Whitfield, author of The Problem of Slavery in Early Vermont, 1777-1810, writes that slavery in Vermont was gradually phased out over a period of multiple decades. Additionally, the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) staff write in “Vermont 1777: Early Steps Against Slavery” that even though “Vermont, Rhode Island, and Connecticut abolitionists achieved laudable goals, each state created legal strictures making it difficult for ‘free’ blacks to find work, own property or even remain in the state” and that Vermont’s 1777 constitution’s “wording was vague enough to let Vermont’s already-established slavery practices continue.” Even when slavery was finally outlawed in the Northern states, their economies were fully intertwined with the institution of slavery. Every occupation and institution from barrel makers to bankers to insurance companies to the textile industry and many more were connected to slavery. The authors of Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited from Slavery describe how New York City mayor Fernando Wood pushed for his city’s secession from the Union during the Civil War because “the lifeblood of New York City’s economy was cotton, the product most closely identified with the South and its defining system of labor: the slavery of millions of people of African descent.” Research more about this great American Champion event and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American civil rights activist who became a lawyer, a women’s rights activist, Episcopal priest, and author.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American civil rights activist who became a lawyer, a women’s rights activist, Episcopal priest, and author. Drawn to the ministry in 1977, she was the first African-American woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest, in the first year that any women were ordained by that church. Born in Baltimore, Maryland, she was virtually orphaned when young, and she was raised mostly by her maternal grandparents in Durham, North Carolina. At the age of 16, she moved to New York City to attend Hunter College, and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in English in 1933. In 1940, she sat in the whites-only section of a Virginia bus with a friend, and they were arrested for violating state segregation laws. This incident, and her subsequent involvement with the socialist Workers’ Defense League, led her to pursue her career goal of working as a civil rights lawyer. She enrolled in the law school at Howard University, where she also became aware of sexism. She called it “Jane Crow”, alluding to the Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation in the Southern United States. She graduated first in her class, but she was denied the chance to do post-graduate work at Harvard University because of her gender. She earned a master’s degree in law at University of California, Berkeley, and in 1965 she became the first African American to receive a Doctor of Juridical Science degree from Yale Law School.As a lawyer, she argued for civil rights and women’s rights. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Chief Counsel Thurgood Marshall called her 1950 in his book, States’ Laws on Race and Color, the “bible” of the civil rights movement. She served on the 1961–1963 Presidential Commission on the Status of Women, being appointed by John F. Kennedy. In 1966 she was a co-founder of the National Organization for Women. Ruth Bader Ginsburg named her as a coauthor of a brief on the 1971 case Reed v. Reed, in recognition of her pioneering work on gender discrimination. This case articulated the “failure of the courts to recognize sex discrimination for what it is and its common features with other types of arbitrary discrimination.” She held faculty or administrative positions at the Ghana School of Law, Benedict College, and Brandeis University.In 1973, she left academia for activities associated with the Episcopal Church. She became an ordained priest in 1977, among the first generation of women priests. She struggled in her adult life with issues related to her sexual and gender identity, describing herself as having an “inverted sex instinct”. She had a brief, annulled marriage to a man and several deep relationships with women. In her younger years, she occasionally had passed as a teenage boy. A number of scholars, including a 2017 biographer, have retroactively classified her as transgender. In addition to her legal and advocacy work, she published two well-reviewed autobiographies and a volume of poetry. Her volume of poetry, Dark Testament, was republished in 2018.Today in our History – July 1, 1985 – Anna Pauline “Pauli” Murray (November 20, 1910 – July 1, 1985) died.Pauli Murray was born Anna Pauline Murray in Baltimore, Maryland. After her parents’ death, she spent her childhood in North Carolina and New York. After graduating from Hunter College in 1928, she shortened her name to Pauli to embrace a more androgynous identity. During the Great Depression, Murray worked for the Works Progress Administration and the Workers Defense League and taught for the New York City Remedial Reading project.Murray was arrested in 1940 for disorderly conduct on an interstate bus trip where she challenged the constitutionality of segregating bus passengers. This incident, coupled with her time working with the Workers Defense League, inspired her to attend law school at Howard University. While there, she participated in civil rights protests in an attempt to desegregate public facilities. She also joined with George Houser, James Farmer, and Bayard Rustin to form the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Murray graduated from Howard with honors and planned on completing a post-graduate fellowship at Harvard University. She was denied admission at Harvard because of her gender. She ultimately finished her post-graduate work at UC Berkeley School of Law. Soon after, she published States’ Laws on Race and Color, regarded as the “bible” of civil rights work. She went onto receive her J.S.D. from Yale University, the first African American to receive this degree.After several appointments at universities around the country, Murray decided to devote her life to her Christian beliefs. In 1977, Murray became the first African American woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest. She worked in a parish in Washington, D.C., based in ministry to the sick until her retirement in 1982. Murray died of pancreatic cancer in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on July 1, 1985.Researchers have discovered that Murray struggled with her sexuality and gender identity during her lifetime. Rosalind Rosenberg, author of Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray, asserts that Murray identified as a transgendered man but did not have the information or acceptance available during her lifetime to describe it. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

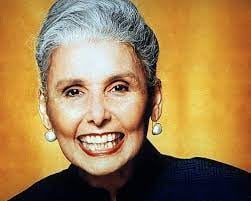

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was was an American singer, dancer, actress, and civil rights, activist.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was was an American singer, dancer, actress, and civil rights activist. Horne’s career spanned over 70 years, appearing in film, television, and theater. Horne joined the chorus of the Cotton Club at the age of 16 and became a nightclub performer before moving to Hollywood.Horne advocated for human rights and took part in the March on Washington in August 1963. Later she returned to her roots as a nightclub performer and continued to work on television, while releasing well-received record albums.She announced her retirement in March 1980, but the next year starred in a one-woman show, Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music, which ran for more than 300 performances on Broadway. She then toured the country in the show, earning numerous awards and accolades.Horne continued recording and performing sporadically into the 1990s, retreating from the public eye in 2000. Horne died of congestive heart failure on May 9, 2010, at the age of 92.Today in our History – June 30, 1917 – Lena Mary Calhoun Horne (June 30, 1917 – May 9, 2010) was born.Lena Horne was notable twentieth century woman associated with American entertainment industry and Civil Rights Movement. Before moving to Hollywood she became a nightclub performer at the age of sixteen. She was once blacklisted for her politically controversial role in the Red Scare.Lena Mary Calhoun Horne was born on June 30, 1917 in Bedford–Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. She is supposedly descended from the John C. Calhoun family. Her family is a mixture of European American, Native American, and African-American who belonged to middle-upper-class stature in the society.Her father was involved in gambling business and when she was three years old, he left his family. Horne’s mother was an actress with a black theatre troupe and traveled extensively, thus she was mainly raised by her grandparents. She was sent to live in Georgia at the age of five.After many years of travel with her mother, she lived with her uncle, Frank S. Horne, for two years. Upon their return to New York from Atlanta, Horne attended Girls High School in Brooklyn. Before earning her diploma certificate, she dropped out of the school.Later she moved in with her father in Pittsburg as she turned eighteen. She stepped into entertainment industry in 1933, and joined the chorus line of the Cotton Club. Afterwards, she recorded her first record release after joining Noble Sissle’s Orchestra.Subsequent to her separation from her first husband, Horne went on a tour with Charlie Barnet. Growing tired of frequent travel, she left the band. NBC featured her on popular jazz series The Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street as a lead vocalist.Moreover, Lena made appearance in a few musicals as well. The low-budget musical, The Duke is Tops was released in 1938. In 1942, she signed a long-term contract with a major Hollywood studio, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. She also worked in a popular radio series Suspense, playing the role of a nightclub singer.Her debut with MGM studio was in Panama Hattie (1942). Also she performed the title song of Stormy Weather. The film was loosely based on the life of Adelaide Hall (1943). Her other popular works include the musical, Cabin in the Sky. However, she was never offered the lead role because of strong racial discrimination still existing at the core of America. In fact, the films were twice edited because some of the states were against black artists on screen.Therefore, most of Lena’s appearances in the films were stand-alone sequences that sometimes seemed detached from the film entirely. One of the scenes featuring Horne taking a bubble bath and signing “Ain’t it the Truth” was removed from the movie as the film executives called it too “risqué”.Despite the extreme racial discrimination against blacks, Lena managed to be elected to serve on the Screen Actors Guild board of directors, which was a milestone for her. The Hollywood blacklisted her for her strong political views in 1950s.By then Horne was disappointed in Hollywood for its hypocrisy and unfair treatment of black artists. Thus she decided to head back to her nightclub career. She became one of the premier nightclub performers. In 1957, she released a live-recorded album, Lena Horne at the Waldorf-Astoria, which was received raving reviews and response from the listeners. The album became the biggest selling record by a female artist. Furthermore, Lena Horne was nominated for a Tony Award for “Best Actress in a Musical” as well.Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

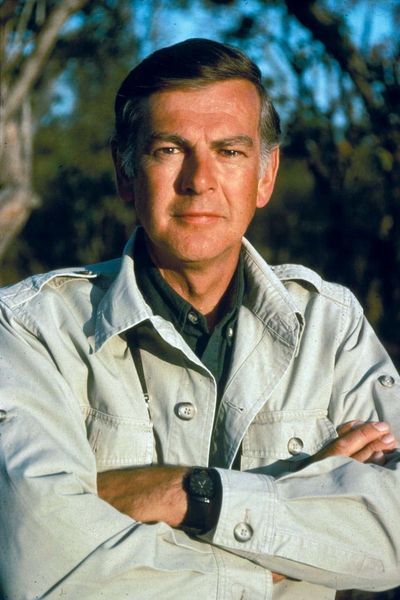

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American paleoanthropologist.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American paleoanthropologist. He is known for discovering – with Yves Coppens and Maurice Taieb – the fossil of a female hominin australopithecine known as “Lucy” in the Afar Triangle region of Hadar, Ethiopia.Today in our history – June 28, 1943 – Donald Carl Johanson is born.Johanson was born in Chicago, Illinois to native parents, the nephew of wrestler Ivar Johansson. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign in 1966, and his master’s degree (1970) and PhD (1974) from the University of Chicago. At the time of the discovery of Lucy, he was an associate professor of anthropology at Case Western Reserve University.In 1981, he established the Institute of Human Origins in Berkeley, California which he later moved to Arizona State University in 1997. Johanson holds an honorary doctorate from Case Western Reserve University, and was awarded an Honorary Doctorate by Westfield State College in 2008. He is an atheist.Lucy was discovered in Hadar, Ethiopia on November 24, 1974, when Johanson, coaxed away from his paperwork by graduate student Tom Gray for a spur-of-the-moment survey, caught the glint of a white fossilized bone out of the corner of his eye, and recognized it as hominin.Forty percent of the skeleton was eventually recovered, and was later described as the first known member of Australopithecus afarensis. Johanson was astonished to find so much of her skeleton all at once. Pamela Alderman, a member of the expedition, suggested she be named “Lucy” after the Beatles’ song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” which was played repeatedly during the night of the discovery.A bipedal hominin, Lucy stood about three and a half feet tall; her bipedalism supported Raymond Dart’s theory that australopithecines walked upright. Johanson and his team concluded from Lucy’s rib that she ate a plant-based diet, and from her curved finger bones that she was probably still at home in trees.They did not immediately see Lucy as a separate species, but considered her an older member of Australopithecus africanus. The discovery, however, of several more skulls of similar morphology persuaded most palaeontologists to classify her as a species called afarensis.Johanson and Maitland A. Edey won a 1982 U.S. National Book Award in Science for the first popular book about this work, Lucy: The Beginnings of Humankind.AL 333, commonly referred to as the “First Family,” is a collection of prehistoric homininid teeth and bones of at least thirteen individuals that were also discovered in Hadar by Johanson’s team in 1975. Generally thought to be members of the species Australopithecus afarensis, the fossils are estimated to be about 3.2 million years old.· In 1976, Johanson received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.· In 1991, the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSICOP) awarded Johanson their highest honor, the In Praise of Reason award.· On October 19, 2014, Johanson gave the second annual Patrusky Lecture.· On October 24, 2014, Johanson accepted the “Emperor Has No Clothes” award at the Freedom From Religion Foundation 37th annual convention.·Asteroid 52246 Donaldjohanson, a target of the Lucy mission was named in his honor. The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on December 25, 2015 (M.P.C. 97569).Since 2013, Johanson has been listed on the Advisory Council of the National Center for Science Education. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American professional football player who was a fullback and linebacker for the Cleveland Browns in the All-America Football Conference (AAFC) and National Football League (NFL).

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American professional football player who was a fullback and linebacker for the Cleveland Browns in the All-America Football Conference (AAFC) and National Football League (NFL).He was a leading pass-blocker and rusher in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and ended his career with an average of 5.7 yards per carry, a record for running backs that still stands. A versatile player who possessed both quickness and size, Motley was a force on both offense and defense. Fellow Hall of Fame running back Joe Perry once called Motley “the greatest all-around football player there ever was”.Today in our History – June 27, 1999 – Marion Motley (June 5, 1920 – June 27, 1999) dies.Motley was also one of the first two African-Americans to play professional football in the modern era, breaking the color barrier along with teammate Bill Willis in September 1946, when the two played their first game for the Cleveland Browns.Motley grew up in Canton, Ohio. He played football through high school and college in the 1930s before enlisting in the military during World War II. While training in the U.S. Navy in 1944, he played for a service team coached by Paul Brown. Following the war, he went back to work in Canton before Brown invited him to try out for the Cleveland Browns, a team he was coaching in the newly formed AAFC.Motley made the team in 1946 and became a cornerstone of Cleveland’s success in the late 1940s. The team won four AAFC championships before the league dissolved and the Browns were absorbed by the more established NFL. Motley was the AAFC’s leading rusher in 1948 and the NFL leader in 1950, when the Browns won another championship.Motley and fellow black teammate Bill Willis contended with racism throughout their careers. Although the color barrier was broken in all major American sports by 1950, the men endured shouted insults on the field and racial discrimination off of it.”They found out that while they were calling us niggers and alligator bait, I was running for touchdowns and Willis was knocking the shit out of them,” Motley once said. “So they stopped calling us names and started trying to catch up with us.” Focused exclusively on winning, Brown did not tolerate racism within the team.Slowed by knee injuries, Motley left the Browns after the 1953 season. He attempted a comeback in 1955 as a linebacker for the Pittsburgh Steelers but was released before the end of the year. He then pursued a coaching career, but was turned away by the Browns and other teams he approached.He attributed his trouble finding a job in football to racial discrimination, questioning whether teams were ready to hire a black coach. Motley was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1968.Motley was born in Leesburg, Georgia and raised in Canton, Ohio, where his family moved when he was three years old.[4] After going to elementary and junior high schools in Canton, Motley attended Canton McKinley High School, where he played on the football and basketball teams. He was especially good as a football fullback, and the McKinley Bulldogs posted a win-loss record of 25–3 during his tenure there. The team’s three losses all came against Canton’s chief rivals, a Massillon Washington High School team led by coach Paul Brown.After he graduated, Motley enrolled in 1939 at South Carolina State College, a historically black school in Orangeburg, South Carolina. He transferred before his sophomore year to the University of Nevada, where he was a star on the football team between 1941 and 1943. As a punishing fullback for the Wolf Pack, Motley played against powerful West Coast teams including USF, Santa Clara, and St. Mary’s. He suffered a knee injury in 1943 and returned to Canton to work after dropping out of school.As United States involvement in World War II intensified, Motley joined the U.S. Navy in 1944 and was sent to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station. There he played for the Great Lakes Navy Bluejackets, a military team coached by Paul Brown, who was serving in the Navy during an extended leave from his job as head coach of The Ohio State University’s football team.[4] Motley played fullback and linebacker at Great Lakes, and was an important component of the team’s offense and defense. The highlight of his time at Great Lakes was a 39–7 victory over Notre Dame in 1945. Motley was eligible for discharge before the game – it was the final match of the season and the last military game of World War II – but he stayed on to play. Motley put up an impressive performance, thanks in part to Brown’s experimentation with a new play: a delayed handoff later called the draw play.After the war, Motley went back to Canton and began working at a steel mill, planning to return to Reno in 1946 to finish his degree. That summer, however, Paul Brown was coaching a team in the new All-America Football Conference (AAFC) called the Cleveland Browns. Motley wrote to Brown asking for a tryout, but Brown declined, saying he already had all the fullbacks he needed. At the beginning of August, however, Brown invited Bill Willis, another African-American star, to try out for the team at its training camp in Bowling Green, Ohio. Ten days later, Brown invited Motley to come, too. “I think they felt [Willis] needed a roommate,” Motley later said. “I don’t think they felt I’d make the team. I’m glad I was able to fool them.”Both Motley and Willis made the team and became two of the first African-Americans to play professional football in the modern era. The Los Angeles Rams of the National Football League had signed the only other black players in pro football earlier that year: Kenny Washington and Woody Strode. The four men broke football’s color barrier a seven months before Jackie Robinson was promoted from the Class AAA Montreal Royals to join the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Motley felt the Browns would likely be his only opportunity to make a career of football. “I knew this was the one big chance in my life to rise above the steel mill existence, and I really wanted to take it,” he said.Motley was signed to a contract worth $4,500 a year ($58,999 in 2019 dollars). With the Browns, he joined a potent offense led by quarterback Otto Graham, tackle and placekicker Lou Groza and receivers Dante Lavelli and Mac Speedie. He was a force to be reckoned with in the AAFC, and helped the team win every championship in the league’s four years of existence between 1946 and 1949.He had a combination of quickness and power – he was listed at 238 pounds – that helped him plow through tacklers. He was also an able pass blocker and played on defense as a linebacker. Motley rushed for an average of 8.2 yards per carry in his first season. His forte was the trap play, a scheme where a defensive lineman was allowed to come across the line of scrimmage unblocked, opening up space for Motley to run. He led the league in rushing in 1948 as the Browns posted a perfect 15–0 record. He was the AAFC’s all-time rushing leader when the league folded after the 1949 season and the Browns were absorbed into the more established National Football League (NFL). The Browns had a 47–4–3 overall regular-season win-loss-tie record during the AAFC years as Motley rushed for a total of 3,024 yards.Like other black players in the 1940s and 1950s, Motley faced racist attitudes both on and off the field. Paul Brown would not tolerate discrimination within the team; he wanted to win and would not let anything get in his way. Motley and Willis, however, were sometimes stepped on and called names during games. “Sometimes I wanted to just kill some of those guys, and the officials would just stand right there,” Motley said many years later. “They’d see those guys stepping on us and heard them saying things and just turn their backs. That kind of crap went on for two or three years until they found out what kind of players we were.” Motley and Willis did not travel to one game against the Miami Seahawks in the Browns’ early years after they received threatening letters. Another time in Miami, Motley and Willis were told they were not welcome at the hotel where the team was staying. Brown threatened to relocate the entire team, and the hotel’s management backed down.Attitudes toward race in America began to change after the war, which had caused social and political upheaval and prompted people to think about the future with more ambition and confidence. Although progress was slow and racially motivated hostility continued for many years, the color barrier was broken in all major sports by 1950. Many of Motley and Willis’s teammates on the Browns were used to playing with black players in college, where teams were integrated across most of the country. The presence of Motley and Willis, meanwhile, contributed to strong attendance at many of the Browns’ early games as large black audiences came to watch them. By one estimate, 10,000 black fans saw the Browns play their first game.Aided by Motley’s swiftness and size, the Browns won the NFL championship in 1950, their first season in the league. In October 1950, Motley set an NFL record that stood for more than 52 years when he averaged over 17 yards per rush against the Pittsburgh Steelers, with 188 yards on 11 carries. In December 2002, quarterback Michael Vick of the Atlanta Falcons rushed for 173 yards on 10 carries against the Minnesota Vikings, eclipsing Motley’s average. Motley also had a 69-yard rushing and 33-yard receiving touchdowns in the game. While Motley did not factor in the Browns’ championship game win against the Los Angeles Rams, he led the league in rushing with 810 yards in 1950 despite averaging fewer than 12 carries per game. He was a unanimous first-team All-Pro selection.By the 1951 season, Motley started to feel the physical effects of his hard-hitting, up-the-middle running style. He suffered a knee injury in training camp, and he was getting older; by the time the season was in full swing, he was 31. Motley only ran for 273 yards and one touchdown that year, an uncharacteristically low total. Despite Motley’s troubles, the Browns made the championship game again after winning the American Conference with an 11–1 record. Cleveland, however, lost the title game to the Rams, 24–17. Motley had just five carries and 23 yards.Motley’s knees continued to bother him in 1952. While he showed occasional signs of his old form that season, it became clear to the Browns’ coaching staff that he was no longer in his prime. Motley finished the year with 444 yards of rushing and 4.3 yards per carry, a career low. The Browns finished with an 8–4 record but still captured the conference title and secured another spot in the NFL championship game. Motley performed well in that matchup against the Detroit Lions, rushing for 95 yards. The Browns, however, lost 17–7.The 1953 season was no better for Motley, whose effectiveness was again limited by injury. Cleveland finished with an 11–1 record and faced Detroit in the championship for the second year in a row. As Motley’s production declined, the Browns relied on Otto Graham’s passing to Lavelli and receiver Ray Renfro, who also lined up as a running back. Motley did not participate in the championship game that year, another loss to the Lions.Motley thought he could come back and play a ninth season in 1954, and showed up to training camp to prove it. Paul Brown, however, thought otherwise. Dogged by injuries and 34 years old, Motley quit before the season began, after Brown said he would otherwise be cut from the team. “Marion realized that his knee was weak and did not feel that it was coming around,” Brown said at the time. “He was one of the truly fine fullbacks in his prime, the type that comes along once in a lifetime. I certainly never will forget some of his runs and I imagine Cleveland football fans feel the same.”Motley took the 1954 season off and attempted a comeback in 1955 after the Browns, who still had rights to Motley under his contract, traded him to the Pittsburgh Steelers for Ed Modzelewski. In Pittsburgh he played seven games as a linebacker, but the Steelers released him before the end of the season. In his eight years in the AAFC and NFL, Motley had rushed for 4,720 yards and averaged 5.7 yards per carry. His career rushing average is still an all-time record for running backs.After ending his playing career for good, Motley asked Brown about a coaching job with the team. Brown, however, rejected his overtures, saying Motley should instead look for work at a steel mill – the very career football was his ticket out of. Unable to find coaching opportunities in the NFL, he worked as a whisky salesman in the early 1960s. He got occasional scouting assignments from the Browns, but as the Civil Rights Movement began to coalesce in 1965, he issued a statement saying he had been refused a permanent coaching position by the team numerous times. He applied for a coaching job in 1964, he wrote, and was told that there were no vacancies. The Browns then hired Bob Nussbaumer as an assistant.”When I heard of the hiring of a new assistant, I began to wonder if the full reason is whether or not the time is ripe to hire a Negro coach in Cleveland on the professional level,” he wrote. Art Modell, the Browns’ owner, responded by saying the team filled its coaching positions based on ability and experience, not race. “We are represented by scouts at every major Negro school. And we now have 12 Negroes signed for the 1965 season,” he said.Motley asked Otto Graham for a job with the Washington Redskins when Graham was head coach there in the late 1960s, but he was again turned away. Motley also signed on to coach an all-girl professional football team called the Cleveland Dare Devils in 1967. By 1969, the team had only played a few exhibition games as Cleveland theatrical agent Syd Freedman struggled to drum up interest in a women’s league. Later in life, Motley worked for the U.S. postal service in Cleveland, Harry Miller Excavating Suffield, Ohio, the Ohio Lottery and for the Ohio Department of Youth Services in Akron. He died in 1999, twenty-two days after his 79th birthday, of prostate cancer.In 1968, Motley became the second black player voted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, located in his hometown of Canton. Having played successfully as a fullback and pass blocker on offense and as a linebacker on defense, he is seen as one of the best all-around players in football history. Blanton Collier, an assistant who took over as the team’s head coach after Paul Brown’s firing in 1963, said Motley “had no equal as a blocker. He could run with anybody for 30 yards or so. And this man was a great, great linebacker.”Most of Motley’s runs were trap plays up the middle, but he had the speed to run outside. “There’s no telling how much yardage I might have made if I ran as much as some backs do now,” he once said. Running back Jim Brown surpassed Motley’s rushing records in the early 1960s, but many of Motley’s coaches and fellow players regarded Motley as the better player, in part because of his strength as a blocker. “There is no comparison between Jim Brown and Marion Motley,” Graham said at a luncheon in Canton in 1964. “Motley was the greatest all-around fullback.”In his books The Thinking Man’s Guide to Pro Football and The New Thinking Man’s Guide To Pro Football, football writer Paul Zimmerman of Sports Illustrated called Motley the best player in the history of the sport. He was named to the NFL’s 75th Anniversary All-Time Team in 1994.In November 2019, Motley was selected as one of the twelve running backs on the NFL 100 All-Time Team. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!