GM – FBF – Today, I want to share with you a story about a man who is a civil rights Icon and also the first Black Man to run for President of the United States.

Remember – “At the end of the day, we must go forward with hope and not backward by fear and division”. Jesse Jackson

Today in our History July 20, 2017 – Jackson wins another award.

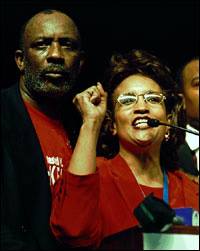

Reverend Jesse L. Jackson Sr. received the highest honor presented by the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA) at its annual convention in Norfolk, Virginia.

The legendary activist received the NNPA Lifetime Legacy Award for his decades of service as one of the country’s foremost civil rights, religious and political figures.

After a video tribute that chronicled Jackson’s life and a surprise solo performance of “Hero,” by Jackson favorite, Audrey DuBois Harris, the iconic preacher accepted the award from NNPA President and CEO Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis, Jr., and NNPA Chairman Dorothy R. Leavell.

“I’m not easy to surprise,” Jackson told the crowd, which gave him a standing ovation as he headed to the podium to accept the honor.

The Presidential Medal of Freedom winner, Jackson has been called the “Conscience of the Nation,” and “The Great Unifier,” challenging America to be inclusive and to establish just and humane priorities for the benefit of all.

Born in 1941 in Greenville, South Carolina, Jackson began his theological studies at Chicago Theological Seminary, but deferred his studies when he began working full time in the Civil Rights Movement alongside Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

“This honor takes on a special meaning for me because my first job was selling the ‘Norfolk Journal and Guide’ newspaper and then the ‘Baltimore AFRO-American’ and then the ‘Pittsburgh Courier,’” Jackson said of the iconic Black-owned newspapers. “We couldn’t see the other side of Jackie Robinson. We couldn’t see the other side of Sugar Ray Robinson,” he said, noting that the Black Press told the full stories of those sports heroes.

He reminisced about the fateful night in Memphis in 1968 when an assassin’s bullet cut down King.

“I was with Dr. King on that chilly night in Memphis and I went to the phone to talk to Mrs. King. I couldn’t really talk,” he said. “I told her, ‘I think Dr. King was shot in the shoulder,’ even though I knew he was shot in the neck. I just couldn’t say it.”

During the ceremony, Leavell and Chavis said Jackson has carried King’s legacy well.

“We still need him,” Leavell said of Jackson.

Chavis called Jackson a “long-distance runner who’s made a difference not only in this country, but all over the world.”

Leavell recalled Jackson’s historic run for the presidency in 1984 in a campaign that registered more than 1 million new voters and catapulting Democrats in their successful effort to regain control of the Senate.

Four years later, Jackson ran again, this time registering more than 2 million new voters and earning 7 million popular votes.

“It’s a wonder that my neighbors didn’t call the police the night he gave that iconic speech at the Democratic National Convention [in 1984],” said Leavell, whom Jackson presided over her wedding ceremony more than 40 years ago. “There was so much emotion that night that I felt, they told me that I could be anything that I wanted to be,” Leavell said, pointing to Jackson and photographers flocked to take pictures of the civil rights leader while holding his coveted NNPA award.

Dubois Harris said Jackson is a “King of a man,” and, although she had been under the weather all week, nothing would stop her from attending Jackson’s big night, she said.

“We stand on his shoulders,” Dubois Harris said. “He continues to be a pioneer of civil rights and humanity and he’s all that’s good and right in the world.”

Over decades, Jackson has earned the respect and trust of presidents and dignitaries and his Rainbow PUSH organization has aided countless Black and minority families with various struggles.

But his work not only has helped the poor or minorities.

In 1984, Jackson secured the release of captured Navy Lt. Robert Goodman from Syria, and he also help shepherd the release of 48 Cuban and Cuban-American prisoners in Cuba.

Jackson was the first American to bring home citizens from the United Kingdom, France, and other countries who were held as human shields by Saddam Hussein in Kuwait and Iraq in 1990.

He also negotiated the release of U.S. soldiers held hostage in Kosovo and, in 2000, Jackson helped negotiate the release of four journalists working on a documentary for Britain’s Channel 4 network who were held in Liberia.

Jackson said President Trump should and can be defeated, with the aid of the Black Press, who this year has led a drive to register 5 million new African-American voters.

“The first time I saw an image of Black achievement was in the Black Press,” Jackson said. “Today, the Black Press is more important than ever. This is the season of ‘Fake News,’ but we need the truth now more than ever.” Research more about Jesse Jackson and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!