GM – FBF – Even during the “Great Depression” people of color were doing outstanding feats but little to no recognition. Read the story of the first national footrace which people of color won three spots in the top ten. Enjoy!

Remember – “Running is nothing more than a series of arguments between the part of your brain that wants to stop and the part that wants to keep going.” – Winner of the Bunion Derby – Andy Payne

Today in our History – The 1928 Bunion Derby: America’s Brush with Integrated Sports.

From March 4 to May 26, 1928, a unique event grabbed the attention of the American public—an eighty-four day, 3,400-mile footrace from Los Angeles to New York City, nicknamed the bunion derby. The 199 starters included five African Americans, a Jamaican-born Canadian, and perhaps as many as fifteen Latinos, Native Americans and Pacific Islanders, representing about ten percent of the competitors. The rest were white. The derby consisted of daily town-to-town stage races that took the men across the length of Route 66 to Chicago, then on other roads to the finish in Madison Square Garden. All were chasing a $25,000 first prize, a small fortune in 1928 dollars.

Given the racial climate of 1928, black participation in the bunion derby seemed a risky venture, better suited for more tolerate racial times, either the 1870’s when professional distance racing was the rage and men of all races were accepted in to its fold, or our modern age, when the sight of African runners leading endurance events is an everyday occurrence. The 1928 race would take the men into the Jim Crow segregated South, where most whites believed blacks lacked the ability to concentrate for anything longer than the sprint distances, and had no business competing against whites.

Bunion derby organizer Charles C. Pyle looked back, longingly, to the 1870’s when the craze for professional distance running gripped the land, and sports promoters could make a fortune sponsoring these events. In those days, most towns and cities had their own indoor tracks, where “pedestrians” raced in six day “go as you please” contests of endurance. Participants were free to run, walk, or crawl around these tracks for six days. They often set up cots inside the track oval and survived on three hours sleep a night. This was a sport of the working classes. Fans bet money on their favorite pedestrians and followed them with all the fervor of today’s NFL fans. Stamina not ethnicity was the single qualifier to become a pedestrian star. Black America had its hero, Haitian born, Frank Hart who made a fortune in the sport and averaged ninety miles a day in one six day endurance race.

C. C. Pyle’s “bunioneers” found far harsher conditions than the pedestrians faced in the calm environment of an indoor track. His men tackled the mostly unpaved and pot-holed Route 66 across the American West, running daily ultra-marathons across one thousand miles of the most challenging terrain on the planet–the ninety-five degree heat of the Mojave Desert, and the freezing mountain passes and thin air of Arizona and New Mexico.

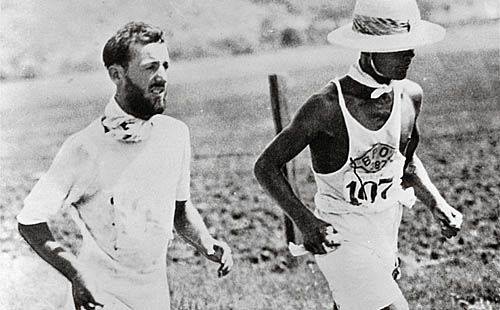

By the time derby reached eastern New Mexico, only ninety-six of the original 199 starters remained, including three of the five African American starters–Eddie Gardner of Seattle, Sammy Robinson of Atlantic City, New Jersey, and Toby Joseph Cotton, Junior of Los Angeles–and Afro-Canadian Phillip Granville, of Hamilton, Ontario. After overcoming all that, the black runners faced a man made hell when Route 66 took them to Texas where the Ku Klux Klan dominated the state legislature and the city governments of Dallas, Forth Worth and El Paso. Gardner, Joseph, Cotton, and Granville were forced out of the communal sleeping tent into a “colored only” tent, then bombarded with death threats and racial slurs as they slogged their way across the muddy, tendon ripping roads of the Texas Panhandle. In McLean, Texas, an angry mob surrounded Gardner’s trainer’s car, and threatened to burn it, claiming that blacks had no business racing against whites. In Western Oklahoma, a farmer trained a shotgun on Eddie Gardner’s back, and rode behind him for an entire day, daring him to pass a white man. After Phillip Granville’s experience with Jim Crow segregation, he began referring to himself as Jamaican Indian, and “anything but negro,” and disassociated myself from the black runners.

This abuse continued across Texas, Oklahoma and Missouri, a total of a thousand miles and twenty-four days of running hell before the derby crossed into Illinois. The men were helped along way by tightly knit black communities in Oklahoma City, Tulsa, and Chandler, Oklahoma, that raised money for them, gave them a clean bed for the night, and a solid meal to keep them going in the face of so much hate. They also were supported and protected by the white runners who had bonded with them like brothers over the brutal miles on Route 66.

The heroism of the black bunioneers was a symbol of hope and pride to black communities they passed along way, and to black America as a whole, who followed the men’s struggle across Texas, Oklahoma and Missouri in the Amsterdam News, California Eagle, Black Dispatch Chicago Defender, and Pittsburgh Courier. The competitors also put to rest the long held belief that blacks were unsuited to long distance running, given that three-fifths of the blacks finished compared to about twenty-five percent of the whites. The derby also showed the nation that blacks and whites could compete against one another even if they were not yet ready to live together in harmony.

On May 26, 1928, fifty-five weary men make their final laps around the track in Madison Square Garden that marked the end of their eighty-four day ordeal. Three of the top ten finishers were runners of color, including the $25,000 first prize winner, Andy Payne, a part Cherokee Indian from Oklahoma, the $5,000 third place winner, Phillip Granville of Canada, and the $1,000 eighth place winner, Eddie Gardner of Seattle. These three bunioneers were cut from the same social cloth as their white competitors—they were blue-collar men who were looking for a piece of the American dream. They did not run for loving cups or medals, but for prize money that could lift a mortgage off a farm, buy a house, or give their children some decent clothes to wear, and in the case of the black runners, they risked their lives to do so. This was a far different mentality from the university athletes and members of athletic clubs who looked down their noses at these working class distance stars, but it was also strikingly modern, a herald of the rise of professional sports in the years to come, where merit, not race determined fame and glory. This race was run in the following year but with no blacks permitted to run becuse of the nation’s depression. I could not find pictures of the winner receiving the winnings and trophy. Make it a champion day!