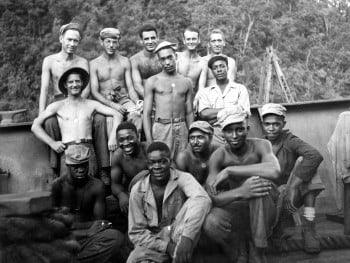

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion unit is the brainchild of Navy Secretary Frank Knox established a committee to investigate the integration of African Americans into the service.Today in our History – April 8, 1942, Navy Secretary Knox announced the Navy would enlist African Americans for the general service, with open enlistment for messmen and the new Seabees.For the Bureau of Yards and Docks (BuDocks), recruitment and organization for African American construction battalions began in April 1942. In September, 880 African American men from 37 states reported to Camp Allen near Norfolk, Va., to become Seabees. To command the new units, BuDocks decided to use southern white men, chosen for “their ability and knowledge in handling” African Americans, but who also received orders to treat all personnel without difference in regard to promotions and assignments. With almost 80 percent of the enlisted men hailing from the South, Rear Adm. Ben Moreell and other senior BuDocks leaders felt this arrangement would help produce a “crack battalion, one which will be proud of themselves and of the Seabees.” On Oct. 24, 1942, the Navy commissioned the African American 34th NCB which shipped out of Port Hueneme, Calif., for the Pacific. The men served 20 months overseas, constructing naval facilities at Espiritu Santo and in the Solomon Islands before returning to Camp Rousseau, Port Hueneme, in October 1944.Around the time the 34th shipped out in January 1943, the second African American construction battalion, the 80th NCB, formed at Camp Allen and commissioned on Feb. 2. After advanced training, the unit moved to Gulfport, Miss., before embarking for assignment to Trinidad in July. As with the 34th, the 80th’s officers and chiefs were also white southerners, although the battalion’s African American personnel mostly came from northern states. Also in July 1943, the first of 15 predominantly African American stevedore construction battalions, termed “specials,” commissioned. All but one of these specials served in the Pacific. These battalions varied considerably in composition from the 34th and 80th NCBs. While still commanded by white officers, the 15th, 17th, 21st, 22nd and 23rd Specials had at least one African American chief petty officer, and the white leadership consisted predominately of non-southerners, less inclined to impose the edifice of segregation in the workplace or at the base camps. While deployed, the men of the two construction battalions performed their assignments admirably and efficiently, but the corrosive effects of commander-imposed racism and discrimination would result in two imbroglios for the Navy. Initially, nothing appeared out of order with either battalion. In the Pacific, the 34th endured Japanese bombing raids and lost five men killed and 35 wounded in their first deployment. Their work in the Solomons garnered numerous commendations and citations for exceptional service. In Trinidad, the 80th constructed a massive airship hangar and other airfield facilities in defense of the Caribbean from German U-boat operations. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Moreell, and other dignitaries visited the unit to inspect their progress.Upon returning to the United States in late 1944, racial tensions in the 34th boiled over at Camp Rousseau, Port Hueneme. While rebuilding for its next deployment, the commanding officer refused to rate any African American as a chief petty officer, and instituted segregated barracks, mess lines and mess huts. African American petty officers were used for unskilled manual labor and never placed in charge of working parties. With morale low, the African American personnel of the battalion staged a hunger strike from March 2-3, 1945, refusing to eat but continuing to perform all scheduled duties. In response, following a Board of Investigation, BuDocks relieved the commanding officer, his executive officer, and 20 percent of the original officers and petty officers. Their replacements were all screened for racial prejudices and southern men were predominately avoided. The new commanding officer, a New Yorker, organized a training program for enlisted personnel to be rerated and ensured that qualified men received the promotions unfairly denied them under the previous commander.For the men of the 80th, discrimination in Gulfport prior to embarkation continued on their transport at sea and at Trinidad, where segregated facilities manifested themselves. After the officer in charge heard complaints from a group of Seabees about racial discrimination in the battalion in September 1943, the commander initiated the discharge of 19 members for what he deemed seditious behavior bordering on mutiny. The commanding officer of the Naval Operating Base, Trinidad and commandant of the Tenth Naval District approved the discharges. The discharged men thereafter contacted the NAACP and the African American media, who demanded answers from the Secretary of the Navy. Under the legal guidance of the NAACP and their special counsel, Thurgood Marshall, a review board upgraded the discharges of 14 of the men in April 1945. Meanwhile, after the battalion returned to Port Hueneme in July 1944, BuDocks ordered the removal of the officer in charge and all original white officers and chiefs, aside from the medical and supply officers, and replaced them with non-southerners. BuDocks could have easily disbanded both battalions and declared African Americans incompatible with the Seabees, but instead chose to recognize the error of its way and change its policies. A Civil Engineer Corps officer noted during the war how when choosing officers for a Seabee unit, “A man may be from the north, south, east or west. If his attitude is to do the best possible job he knows how, regardless of what the color of his personnel is, that is the man we want as an officer for our colored Seabees.” The work of African American units proved equal to that of white units. Leadership – as with any military unit – made the difference in morale and efficiency. This is particularly noted in the African American special battalions, which often reported high morale and performance. After replacing the leadership of the two construction battalions, BuDocks redeployed both units to the Pacific in 1945, where they worked without incident and with high morale.The accomplishments of African American Seabees in World War II demonstrated then and now that the spirit of “Can Do” does not differentiate between age, race or gender. By late 1945 as American forces closed in on Japan, several African American Seabee specials integrated, and white and black Seabees found themselves unloading ships or constructing advance bases, united together for victory. These constituted, arguably, the Navy’s first fully integrated units in the 20th century. Perhaps more importantly for these Seabees, they recognized how their work in the Pacific factored into the fight against discrimination at home. Writing in April 1945, 80th NCB member CM1c Arthur H. Turner of Detroit, Mich., declared: Wherever we go, whatever our assignment may be, we still employ all our talents and efforts to do a good job, one that will be a lasting monument to the Navy and to the Negro race.” Research more about these great American Champions and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

Month: April 2021

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American Christian pastor and Civil Rights leader.

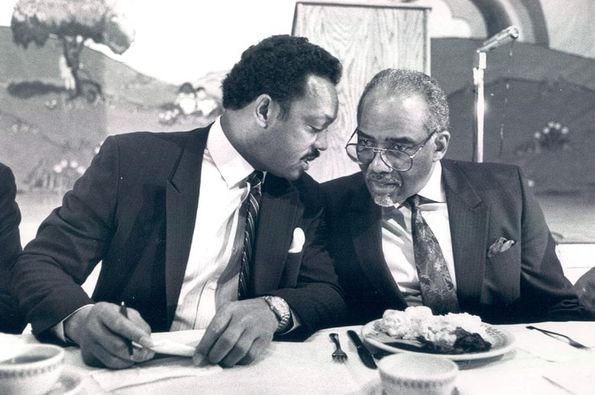

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American Christian pastor and Civil Rights leader. He was the pastor of Mount Zion Baptist Church in Seattle for four decades. He attended the Selma to Montgomery marches in 1965, and he served on the Seattle Human Rights Commission.Samuel B. McKinney was born on December 28, 1926 in Flint, Michigan. He grew up in Cleveland, Ohio, where his father, Wade Hampton McKinney, was a pastor.McKinney graduated from Morehouse College in 1949. He earned a divinity degree from Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School in 1952.The Rev. Dr. Samuel Berry McKinney, 91, a civil-rights leader; pastor emeritus at Mount Zion Baptist Church, Seattle; and supporter of American Baptist Home Mission Societies’ publishing ministry, Judson Press, died April 7 at an assisted-living center in Seattle. He was married to the late Louise (Jones) McKinney for 59 years.He was pastor at Mount Zion Baptist Church for more than 40 years before retiring in 1998. Under his leadership, the congregation grew from 800 to more than 2,500, making Mount Zion the largest black church in Washington state. In 2014, several blocks near the church were renamed “Rev. Dr. S. McKinney Avenue.” He was the first black president of the Church Council of Greater Seattle and a founding member of the National Black Caucus of American Baptist Churches USA. He was known for mentoring aspiring young pastors throughout the United States.At the forefront of advocacy, McKinney was co-founder and first president of the Seattle Opportunities Industrialization Center for vocational training and adult skills development. He was a founding member of the Seattle Human Rights Commission, which won passage of the city’s first fair-housing act. He led construction of the Samuel Berry McKinney Manor for the elderly and working poor. In addition to other civic projects, McKinney helped to launch the city’s first black-owned bank; founded a daycare center and kindergarten; and initiated a scholarship fund.A charter member of the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference—a nonprofit organization that engages African-American faith leaders in social justice issues—the group honored him with its “Beautiful Are Their Feet” award in 2006 for his significant contributions to social justice.In the 1960s, McKinney participated in civil-rights demonstrations in Seattle and across the United States, including the Selma-to-Montgomery voting rights march in 1965. In 1961, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. visited Seattle at the request of McKinney, his college classmate. McKinney was arrested for protesting apartheid outside the South African consulate in Seattle in 1985. At age 86, McKinney continued to address injustice, speaking at a prayer vigil for Trayvon Martin, an unarmed African-American teen who was fatally shot in Florida in 2012.“We have not reached heaven yet,” McKinney said. “We do not live in a nonracist society. …We have to tell the truth, whether we like it or not.”Born Dec. 28, 1926, he was a son of the late Rev. Wade Hampton McKinney and Ruth (Berry) McKinney.McKinney served in the Air Force during World War II. He earned a doctorate of ministry degree and master of divinity degree at what is now known as Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School, Rochester, N.Y., and a bachelor’s degree from Morehouse College, Atlanta.A faithful supporter of Judson Press, McKinney received the Judson Press Ministry Award in 2009. He co-authored “Church Administration in the Black Perspective,” a classic reference manual that remains popular. It was one of two books published in 1976 that launched Judson Press’ acclaimed genre of books for the African-American church.Judson Press will contribute 2018 proceeds from the sales of the revised edition of the book to the “Friends of Judson,” a fund that provides practical resources to graduating seminarians.“In addition to his writing for Judson Press, Dr. McKinney maintained a long and continuous relationship with members of the board of directors, executive directors and staff of ABHMS,” says ABHMS and Judson Press Executive Director Dr. Jeffrey Haggray. “Sitting beside Dr. McKinney during the National Black Caucus dinner during the recent Mission Summit in Portland was my last occasion for conversation and fellowship with Dr. McKinney. His mind was sharp, and his dedication to American Baptist mission and ministry remained strong. We will miss him dearly.” McKinney began his ministry in Providence, Rhode Island, where he was the pastor of Olney Street Baptist Church from 1955 to 1958. He moved to Seattle, Washington, where he served as the pastor of Mount Zion Baptist Church from 1958 to 1998, and from 2005 to 2008.McKinney invited Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. to Seattle in 1961, and he attended the Selma to Montgomery marches in 1965. He served on the Seattle Human Rights Commission. He was also a co-founder of Liberty Bank, “the first black-owned bank in Seattle.”With Floyd Massey Jr., McKinney co-authored Church Administration in the Black Perspective. According to The Los Angeles Times, ” The book outlined the need for strong, charismatic ministers in urban black churches and remains an important reference work in church organization.”McKinney married Louise Jones; they had two daughters.McKinney died on April 7, 2018. Research more about this great American and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

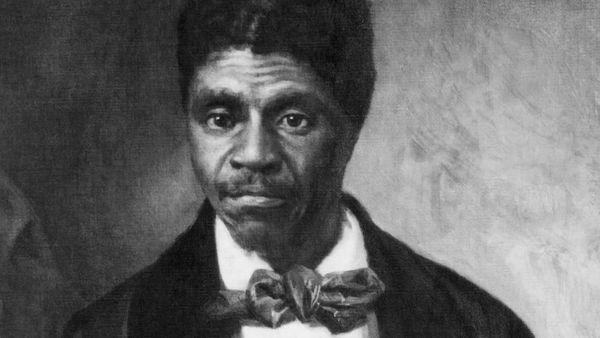

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court in which the Court held that the US Constitution was not meant to include American citizenship for black people, regardless of whether they were enslaved or free, and so the rights and privileges that the Constitution confers upon American citizens could not apply to them.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court in which the Court held that the US Constitution was not meant to include American citizenship for black people, regardless of whether they were enslaved or free, and so the rights and privileges that the Constitution confers upon American citizens could not apply to them.The decision was made in the case of Dred Scott, an enslaved black man whose owners had taken him from Missouri, which was a slave-holding state, into Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory, which were free areas where slavery was illegal.When his owners later brought him back to Missouri, Scott sued in court for his freedom and claimed that because he had been taken into “free” U.S. territory, he had automatically been freed and was legally no longer a slave. Scott sued first in Missouri state court, which ruled that he was still a slave under its law. He then sued in US federal court, which ruled against him by deciding that it had to apply Missouri law to the case. He then appealed to the US Supreme Court.In March 1857, the Supreme Court issued a 7–2 decision against Dred Scott. In an opinion written by Chief Justice Roger Taney, the Court ruled that black people “are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States.”Taney supported his ruling with an extended survey of American state and local laws from the time of the Constitution’s drafting in 1787 that purported to show that a “perpetual and impassable barrier was intended to be erected between the white race and the one which they had reduced to slavery.” Because the Court ruled that Scott was not an American citizen, he was also not a citizen of any state and, accordingly, could never establish the “diversity of citizenship” that Article III of the US Constitution requires for a US federal court to be able to exercise jurisdiction over a case. After ruling on those issues surrounding Scott, Taney continued further and struck down the entire Missouri Compromise as a limitation on slavery that exceeded the US Congress’s constitutional powers.Although Taney and several of the other justices hoped that the decision would permanently settle the slavery controversy, which was increasingly dividing the American public, the decision’s effect was the complete opposite.Taney’s majority opinion suited the slaveholding states, but was intensely decried in all the other states, and the decision was a contributing factor in the outbreak of the American Civil War four years later, in 1861. After the Union’s victory in 1865, the Court’s rulings in Dred Scott were voided by the Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, which abolished slavery except as punishment for a crime, and the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed citizenship for “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.”The Supreme Court’s decision has been widely denounced ever since. Bernard Schwartz said that it “stands first in any list of the worst Supreme Court decisions—Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes called it the Court’s greatest self-inflicted wound.”Junius P. Rodriguez said that it is “universally condemned as the U.S. Supreme Court’s worst decision”. Historian David Thomas Konig said that it was “unquestionably, our court’s worst decision ever.”Today in our History – April 6, 1846 – Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), often referred to as the Dred Scott decision.The economist Charles Calomiris and the historian Larry Schweikart discovered that uncertainty about whether the entire West would suddenly become slave territory or engulfed in combat like “Bleeding Kansas” gripped the markets immediately. The east–west railroads collapsed immediately (although north–south lines were unaffected), causing, in turn, the near-collapse of several large banks and the runs that ensued. What followed the runs has been called the Panic of 1857.The effects of the Panic of 1857, unlike the Panic of 1837, were almost exclusively confined to the North, a fact that Calomiris and Schweikart attribute to the South’s system of branch banking, as opposed to the North’s system of unit banking. In the South’s branch banking system information moved reliably among the branch banks and transmission of the panic was minor. Northern unit banks, in contrast, were competitors and seldom shared such vital informationThe decision was hailed in southern slaveholding society as a proper interpretation of the US Constitution. According to Jefferson Davis, then a US Senator from Mississippi who later became the President of the Confederate States, the Dred Scott case was merely a question of “whether Cuffee should be kept in his normal condition or not.” (“Cuffee” was a common slave name and was also used to refer to a black person, since slavery was a racial caste. Before Dred Scott, Democratic Party politicians had sought repeal of the Missouri Compromise and were finally successful in 1854 with the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act. It allowed each newly-admitted state south of the 40th parallel to vote as to whether to be a slave state or free state. With Dred Scott, Taney’s Supreme Court permitted the unhindered expansion of slavery into all the territories.Thus, Dred Scott decision represented a culmination of what many at that time considered a push to expand slavery. Southerners, who had grown uncomfortable with the Kansas-Nebraska Act, argued that they had a constitutional right to bring slaves into the territories, regardless of any decision by a territorial legislature on the subject. The Dred Scott decision seemed to endorse that view. The expansion of slavery into the territories and resulting admission of new states would mean a loss of northern political power, as many of the new states would be admitted as slave states. Counting three fifths of the slave population for apportionment would add to the slaveholding states’ political representation in Congress.Although Taney believed that the decision represented a compromise that would be a final settlement of the slavery question by transforming a contested political issue into a matter of settled law, the decision produced the opposite result. It strengthened Northern opposition to slavery, divided the Democratic Party on sectional lines, encouraged secessionist elements among Southern supporters of slavery to make bolder demands, and strengthened the Republican Party.In 1859, when defending John Anthony Copeland and Shields Green from the charge of treason, following their participation in John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, their attorney, George Sennott, cited the Dred Scott decision in arguing successfully that since they were not citizens according to that Supreme Court ruling, they could not commit treason. They were acquitted of treason, but found guilty and executed on other charges.Justice John Marshall Harlan was the lone dissenting vote in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which declared racial segregation constitutional and created the concept of “separate but equal”. In his dissent, Harlan wrote that the majority’s opinion would “prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott case.”Charles Evans Hughes, writing in 1927 on the Supreme Court’s history, described Dred Scott v. Sandford as a “self-inflicted wound” from which the court would not recover for many years.In a memo to Justice Robert H. Jackson in 1952, for whom he was clerking, on the subject of Brown v. Board of Education, the future Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist wrote that “Scott v. Sandford was the result of Taney’s effort to protect slaveholders from legislative interference.”Justice Antonin Scalia made the comparison between Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992) and Dred Scott in an effort to see Roe v. Wade overturned:Dred Scott … rested upon the concept of “substantive due process” that the Court praises and employs today. Indeed, Dred Scott was very possibly the first application of substantive due process in the Supreme Court, the original precedent for… Roe v. Wade.Scalia noted that the Dred Scott decision had been written and championed by Taney and left the justice’s reputation irrevocably tarnished. Taney, who was attempting to end the disruptive question of the future of slavery, wrote a decision that worsened sectional tensions and was considered to contribute to the American Civil War.Chief Justice John Roberts compared Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) to Dred Scott, as another example of trying to settle a contentious issue through a ruling that went beyond the scope of the Constitution1977: The Scotts’ great-grandson, John A. Madison, Jr., an attorney, gave the invocation at the ceremony at the Old Courthouse (St. Louis) in St. Louis, a National Historic Landmark, for the dedication of a National Historic Marker commemorating the Scotts’ case tried there.· 2000: Harriet and Dred Scott’s petition papers in their freedom suit were displayed at the main branch of the St. Louis Public Library, following discovery of more than 300 freedom suits in the archives of the U.S. circuit court.· 2006: A new historic plaque was erected at the Old Courthouse to honor the active roles of both Dred and Harriet Scott in their freedom suit and the case’s significance in U.S. history.·2012: A monument depicting Dred and Harriet Scott was erected at the Old Courthouse’s east entrance facing the St. Louis’ Gateway Arch.Research more about this great American disaster and share it with your babies and make it a champion day!

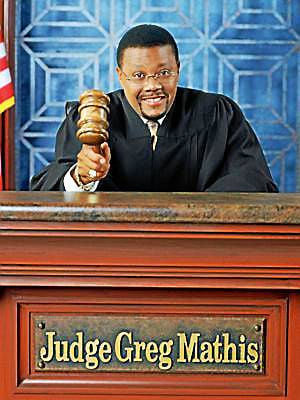

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is a retired Michigan 36th District Court judge turned arbiter of the Daytime Emmy Award–winning, syndicated reality courtroom show.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is a retired Michigan 36th District Court judge turned arbiter of the Daytime Emmy Award–winning, syndicated reality courtroom show. Produced in Chicago, Illinois, his program has been on the air since September 13, 1999 and entered its milestone 20th season beginning on Monday, September 3, 2018. Emanating from the success of his venerable courtroom series, he has also made a name for himself as a prominent leader within the Black American community as a black-culture motivational speaker.He boasts the longest reign of any African American presiding as a court show judge, beating out Judge Joe Brown whose program lasted 15 seasons. He is also the second longest serving television arbitrator ever, behind only Judith Sheindlin of Judge Judy by three seasons.A spiritually inspired play, Been there, Done that, based on his life toured twenty-two cities in the U.S. in 2002. In addition, Inner City Miracle, a memoir, was published by Ballantine Books.Today in our History – April 5, 1960 – Gregory Ellis Mathis was born. Mathis was born in Detroit, Michigan, the fourth of four boys born to Charles Mathis, a Detroit native, and his wife Alice Lee Mathis, a devoted Seventh-day Adventist, nurse’s aide, and housekeeper. Alice (then divorced from Charles) raised Mathis alone in Detroit during the turbulent 1960s and 1970s.Mathis moved to Herman Gardens in 1964 and lived there with the family until roughly 1970. They moved away from the housing complex to avoid rising drug use and rates of violent crime.Judge Mathis’ real father was estranged from him, but associated closely with the Errol Flynns, a past notorious Detroit street gang, that Mathis would eventually join while a teenager. In the 1970s, he was arrested numerous times. While he was incarcerated in Wayne County Jail, as a seventeen-year-old juvenile, his mother visited him and broke the news that she was diagnosed with colon cancer. Mathis was offered early probation because of his mother’s illness.Once out of jail, Mathis began working at McDonald’s, a job he needed to keep in order to maintain his release on probation. A close family friend helped Mathis get admitted to Eastern Michigan University, and he discovered a new interest in politics and public administration. He became a campus activist and worked for the Democratic Party, organizing several demonstrations against South African Apartheid policies. He graduated with a B.S. in Public Administration from the Ypsilanti campus and began to seek employment in Detroit’s City Hall. He also became a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.Mathis began his political career as an unpaid intern, and then became an assistant to Clyde Cleveland, a city council member. It was at this time Mathis took the LSAT and applied to law schools; he was conditionally admitted to the University of Detroit School of Law, which was located in downtown Detroit, walking distance from city hall. He passed a summer course and was officially admitted to the night program which took four years to complete.Mathis was denied a license to practice law for several years after graduating from law school because of his criminal past. He received his J.D. from the University of Detroit Mercy in 1987. In 1995, he was elected a district court judge for Michigan’s 36th District, making him the youngest person in the state to hold the post. During the five years he was on the bench, he was rated in the top five of all judges in the 36th District; there are about thirty judges each year.Mathis was appointed head of Jesse Jackson’s Presidential campaign in the state of Michigan in 1988. Mathis later became head of Mayor Coleman Young’s re-election campaign and after the victory was appointed to run the city’s east side city hall.Mathis has continued to be involved in politics after rising to national entertainment prominence through his television show. Urban politics and African-American movements have been his focus. Most recently, Mathis was invited by the Obama administration to be a part of “My Brothers Keeper”, a White House Initiative to empower boys, and men of color. On June 4, 2011, Detroit-area drivers lined up for blocks as Mathis offered up to $92 worth of free gasoline apiece to the first 92 drivers to show up at a northwest Detroit Mobil station. He told the Detroit Free Press it was a gift to the people who elected him to District Court despite his youthful criminal record. “LA didn’t elect me judge,” he said. “Chicago didn’t elect me judge. Detroiters took a chance on me. It’s just the right thing to do. And when you’re blessed, you have to look out for the rest.” The giveaway took place near the Mathis Community Center, which he funds. Its activities include self-improvement classes, food and clothing assistance, and training for ex-convicts. “No matter what international fame he’s achieved, he’s still a hometown guy,” said WMXD-FM’s Frankie Darcell, who announced the location on the air. “Everybody’s happy. I’m happy,” said gas station owner Mike Safiedine. “The people need it, especially (because) the price is very high.”In September 2008, Mathis wrote a novel called Street Judge, based on the life of a judge who solves murders. It was co-written by Zane, a well-known erotic series writer of Zane’s Sex Chronicles. Mathis also wrote a book entitled Of Being a Judge to Criminals and Such.Following his time spent in the Herman Gardens mixed-income housing, Mathis remained devoted to aiding families in the area. In 2003, he lobbied city officials on the behalf of former Herman Gardens residents, imploring lawmakers to allow these individuals first chance to move into new apartments built where Herman Gardens once stood. Mathis met his wife, Linda, a fellow EMU student, shortly after his mother’s death. They would go on to have four children together, a daughter Jade, born May 1985, daughter Camara, born October 1987, son Greg Jr. born January 1989 and son Amir, born July 1990. Mathis who is a member of the City Temple Seventh-day Adventist Church, was awarded the Black History Achievement Award from Oakwood University, which he says is the most meaningful award he has received. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was fatally shot in North Charleston, South Carolina, by Michael Slager, a North Charleston police officer.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was fatally shot in North Charleston, South Carolina, by Michael Slager, a North Charleston police officer. Slager had stopped him for a non-functioning brake light. Slager was charged with murder after a video surfaced showing him shooting him from behind while he was fleeing, which contradicted Slager’s report of the incident. The race difference led many to believe that the shooting was racially motivated, generating a widespread controversy. The case was independently investigated by the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division (SLED). The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Office of the U.S. Attorney for the District of South Carolina, and the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division conducted their own investigations.In June 2015, a South Carolina grand jury indicted Slager on a charge of murder. He was released on bond in January 2016. In late 2016, a five-week trial ended in a mistrial due to a hung jury. In May 2016, Slager was indicted on federal charges including violation of his civil rights and obstruction of justice. In a May 2017 plea agreement, Slager pleaded guilty to federal charges of civil rights violations, and he was returned to jail pending sentencing. In return for his guilty plea, the state’s murder charges were dropped. In December 2017, Slager was sentenced to 20 years in prison, with the judge determining the underlying offense was second-degree murder.Today in our History – April 4, 2015 – Walter Scott, was fatally shot in North Charleston, South Carolina.At 9:30 a.m., April 4, 2015, in the parking lot of an auto parts store at 1945 Remount Road, Slager stopped Scott for a non-functioning third brake light. Scott was driving a 1991 Mercedes, and, according to his brother, was headed to the auto parts store when he was stopped. The video from Slager’s dashcam shows him approaching Scott’s car, speaking to Scott, and then returning to his patrol car. Scott exited his car and fled with Slager giving chase on foot. Slager pursued Scott into a lot behind a pawn shop at 5654 Rivers Avenue, and the two became involved in a physical altercation. At some point before or during the struggle, Slager fired his Taser, hitting Scott. Scott fled, and Slager drew his .45-caliber Glock 21 handgun, firing eight rounds at him from behind. The coroner’s report stated that Scott was struck a total of five times: three times in the back, once in the upper buttocks, and once on an ear.During Slager’s state trial, forensic pathologist Lee Marie Tormos testified that the fatal wound was caused by a bullet that entered Scott’s back and struck his lungs and heart. Immediately following the shooting, Slager radioed a dispatcher, stating, “Shots fired and the subject is down. He grabbed my Taser.” When Slager fired his gun, Scott was approximately 15 to 20 feet (5 to 6 m) away and fleeing. In the report of the shooting filed before the video surfaced, Slager said he had feared for his life because Scott had taken his Taser, and that he shot Scott because he “felt threatened”.A passenger in Scott’s car, reported to be a male co-worker and friend, was later placed in the back of a police vehicle and briefly detained. A toxicology report showed that Scott had cocaine and alcohol in his system at the time of his death.The level of cocaine was less than half the average amount for “typical impaired drivers”, according to the report. Tormos testified that Scott did not test positive for alcohol. Critics, such as the Reverend Al Sharpton and the predominantly African-American National Bar Association, called for the prosecution of Clarence Habersham, the second officer seen in the video, alleging an attempted cover-up and questioning “whether Habersham omitted significant information from his report.” Critics also questioned Habersham’s statement in his report that he “attempted to render aid to the victim by applying pressure to the gunshot wounds,” saying that the videotape shows little attempt to aid Scott after the shooting. Slager’s original lawyer, David Aylor, withdrew as counsel within hours of the release of the video; he did not publicly give a reason for his withdrawal, citing attorney–client privilege. On April 8, the North Charleston city manager announced that the NCPD had fired Slager but would continue to pay for his health insurance because his wife was pregnant. The town’s mayor, Keith Summey, said they had ordered an additional 150 body cameras, enough that one could be worn by every police officer. A GoFundMe campaign was started to raise money for Slager’s defense, but it was quickly shut down by the site. Citing privacy concerns, they declined to go into detail about why the campaign was canceled, saying only that it was “due to a violation of our terms and conditions”.Scott’s funeral took place on April 11, at the W.O.R.D. Ministries Christian Center in Summerville, about 20 miles from North Charleston. Scott’s killing further fueled a national conversation around race and policing. It has been connected to similar controversial police shootings of black men in Missouri, New York, and elsewhere. The Black Lives Matter movement protested Scott’s death. A bill in the South Carolina state house, designed to equip more police officers with body cameras, was renamed for Scott. The Senate set aside $3.4 million to fund it, enough to buy 2,000 cameras for South Carolina officers. In North Charleston, whites make up 37% of the population, but the police department is 80% white. In May 2016, a short documentary film about the shooting called Frame 394 was released by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. The documentary is about Daniel Voshart, a Canadian cinematographer and image stabilization specialist, who claims to have discovered evidence in frame 394 of the shooting video “that challenged the accepted narrative of what transpired between Slager and Scott”; and it follows his “moral dilemma of what to do with this potential key evidence”.Initially, Voshart examined the footage to help indict Slager, having been convinced by the footage that it “was an example of police corruption at its worst”. After clarifying the video and inspecting frame 394, however, he noticed that as Slager began reaching to draw his firearm, it appeared that Scott was still holding Slager’s Taser, “potentially enough to make Slager fear for his life and maybe meet the grounds needed to use lethal force.” It was impactful in Slager’s trial after Voshart showed Slager’s lawyer, Andy Savage, the stabilized video. During the trial, the officer “testified that he did not realize the Taser had fallen behind him when he fired the fatal shots.” Separate investigations were conducted by the FBI, the U.S. Attorney in South Carolina, the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, and the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division (SLED). An autopsy was performed by the Charleston County coroner on April 4, 2015, which showed that Scott had been shot in the back multiple times.The coroner ruled the death a homicide. After the police department reviewed the video,[25] Slager was arrested on April 7 and charged with murder. On June 8, a South Carolina grand jury indicted Slager on the murder charge. The murder charge was the only charge presented to the grand jury. On January 4, 2016, after being held without bail for almost nine months, Slager was released on $500,000 bond. He was confined to house arrest until the trial, which began October 31, 2016.On December 5, the judge declared a mistrial after the jury became deadlocked with 11 of the 12 jurors favoring a conviction. A retrial had been scheduled to begin in August 2017. However, the state charges were dropped as a result of Slager pleading guilty to a federal charge. On May 11, 2016, Slager was indicted on federal charges of violating Scott’s civil rights and unlawfully using a weapon during the commission of a crime. In addition, he was charged with obstruction of justice as a result of his statement to state investigators that Scott was moving toward him with the Taser when he shot him. Slager pleaded not guilty, and a trial was scheduled to begin in May 2017. Slager faced up to life in prison if convicted. On May 2, 2017, as part of a plea agreement, Slager pleaded guilty to deprivation of rights under color of law (18 USC § 242). In return for the guilty plea, the charges of obstructing justice and use of a firearm during a crime of violence were dismissed. On December 7, 2017, U.S. District Judge David C. Norton sentenced Slager to 20 years in prison. Although defense attorneys had argued for voluntary manslaughter, the judge agreed with prosecutors that the “appropriate underlying offense” was second-degree murder.Because there is no parole in the federal justice system, Slager will likely remain in prison about 18 years after credit for time served in jail. He began serving his sentence in Colorado’s Federal Correctional Institution, Englewood in February 2018. An appeal for reduction of sentence was denied in January 2019. As of 2020, Slager, Federal Bureau of Prisons #31292-171, is still at FCI Englewood; his earliest possible release is August 16, 2033.In an out-of-court settlement, the City of North Charleston agreed in October 2015 to pay $6.5 million to Scott’s family. The Walter Scott Notification Act is proposed federal legislation by U.S. Senator Tim Scott of South Carolina to require the reporting of police shootings by any states with federal funding. Research more about this great American tragedy and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American politician and physician.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American politician and physician. He was the first African-American member of the Nebraska Legislature, where he served two terms in the Nebraska House of Representatives (the lower house of what was then a bicameral legislature). He was also the first African American to graduate from the University of Nebraska College of Medicine in Omaha. Today in our History – April 3, 1858 – Matthew Oliver Ricketts (April 3, 1858 – 1917) was born.Ricketts was born to enslaved parents in Henry County, Kentucky in 1858. His parents moved to Boonville, Missouri, after the American Civil War when he was a child, and he completed school there. In 1876 Ricketts earned a degree from the Lincoln Institute (now Lincoln University of Missouri) in Jefferson City, Missouri. In 1880 he moved to Omaha, where he was admitted to the Omaha Medical College. He worked as a janitor to pay his tuition. In March 1884 Ricketts graduated with honors, and soon after opened a medical office in Omaha. Ricketts quickly earned a reputation for “being a very careful physician, as well as an exceedingly likable young man.” With his education and energy, Ricketts became the acknowledged leader of Omaha’s African-American community. He was a charismatic man and controversial speaker. Following the failed candidacy of Nebraska’s first black candidate, Edwin R. Overall, in 1890, Ricketts was elected to the Nebraska House of Representatives in 1892 on the Republican ticket. Rickets served two terms, from 1893 to 1897. He was the first African American to serve in the Nebraska Legislature. Dr. Ricketts was regarded as one of the best orators there and was frequently called upon for his opinions. He is credited with creating Omaha’s Negro Fire Department Company. He helped secure appointments for blacks in city and state government positions, for patronage was an important part of politics before the establishment of merit career civil service for such positions. Ricketts was a member of the black association the Prince Hal Masons, where he was elected Worshipful Master of Omaha Excelsior Lodge No. 110. The African-American Masons were one of many fraternal associations created by African Americans in communities nationwide in the late 19th century as they organized new cooperative ventures.Ricketts addressed the 1906 Grand Convocation of the Freemasons in Kansas City, Missouri. After leaving the Legislature, Ricketts was an unsuccessful candidate for a federal appointee position, chiefly because his appointment was opposed by a Nebraska congressman. Ricketts subsequently moved to St. Joseph, Missouri to continue his medical career in 1903. He practiced there for another 14 years and continued to play a prominent role in politics in that city. Ricketts was active in the Nebraska Legislature, chairing several committees and temporarily chairing the body. He introduced a bill to legalize interracial marriages, which passed the Legislature only to be vetoed by Governor Silas A. Holcomb. He also introduced a bill to prohibit the denial of public services to African Americans. In 1893 Nebraska lawmakers passed a measure prohibiting race-based denial of services. This strengthening of the state’s 1885 civil rights law was led by Ricketts. He was also instrumental in the enactment of a bill that set an age of consent for marriage in Nebraska, relying on a petition of 500 African-American women in Omaha to carry it forward. In 1884 when he graduated from medical school, Ricketts married Alice Nelson. They had three children. Ricketts died in St. Joseph, Missouri, at the age of 64. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion in 1982, he was a black engineer, was convicted for the armed robbery of a fast-food restaurant near Dallas, Texas, and sentenced to life imprisonment.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion in 1982, he was a black engineer, was convicted for the armed robbery of a fast-food restaurant near Dallas, Texas, and sentenced to life imprisonment. This occurred despite conflicts in eyewitness testimony, co-workers’ claims that he was at work at the time of the robbery, and his lack of a prior criminal record. Devoting half of its broadcast to the case, the 60 Minutes team, including executive producer Don Hewitt, producer Suzanne St. Pierre, and correspondent Morley Safer, carefully retraced the events leading to his arrest and conviction.As a result of its investigation, which produced new witnesses and revealed a number of prosecution errors and omissions, He was granted his release in March 1984. For continuing its tradition of excellence in investigative reporting, a Peabody to CBS News’ 60 Minutes: Lenell Geter’s in Jail.Today in our History – April 2, 1982 – Lenell Genter is arrested for armed robbery.In early 1982, a group of six black aerospace engineers, who had recently graduated from South Carolina State University, moved to the predominantly white city of Greenville, Texas, to begin engineering jobs at a large military defense contractor called E-Systems, Inc. Shortly thereafter, a string of armed robberies occurred in the greater Greenville area, including the robberies of a Taco Bell and a Kentucky Fried Chicken in Greenville, and the August 1982 robbery of $615 from a Kentucky Fried Chicken in nearby Balch Springs, Texas.A woman contacted the Greenville police to report having seen two black men sitting in a Volkswagen with a South Carolina license plate, parked at a park two miles away from the Greenville Kentucky Fried Chicken on the day that restaurant was robbed. This car was registered to Lenell Geter, one of the six engineers from South Carolina State University. Geter was 25 years old and engaged to be married in a few months. Greenville Police Detective James Fortenberry obtained a photo of Geter and showed it to the workers at the Taco Bell that had been robbed. One Taco Bell worker hesitantly identified Geter as the robber, and three workers at the Balch Springs KFC later identified him as well. In August 1982, Geter was arrested for robbery, and his roommate, Anthony Williams, another E-Systems engineer, was arrested as his accomplice.Geter hired an attorney, but after a dispute with Geter’s parents, the attorney quit. Geter was then represented by court-appointed attorney Edwin Sigel, who advised him to plead guilty in order to receive leniency in his sentencing. Geter, who had continually insisted that he was innocent, refused to plead.Nine of Geter’s colleagues at E-Systems were able to testify that he was at work on the day of the robberies in question. Though none of his co-workers reported having seen Geter at the precise time of the robbery, Geter’s boss had given him an assignment just before the time of the Balch Springs Kentucky Fried Chicken robbery, located fifty miles away from the E-Systems office, and Geter had returned the completed assignment to the boss a few hours later. “We’re not bleeding hearts, we’re conservative engineers who want criminals punished,” said Ed Garrett, the director of Geter’s division at E-Systems. “But there’s not a shred of evidence that [Geter and Williams] are guilty of a crime. No one wants to call it a racial problem, but if they were white, they would not be in this situation.”Geter emphatically maintained that he was innocent. His co-workers described him as a kind, well-mannered man who read the Bible during his lunch hour, and there was no evidence to link him to the robberies other than the identifications made by several eyewitnesses. Nonetheless, Geter’s all-white jury found him guilty and sentenced him to life in prison. Anthony Williams was tried for another hold-up thought to have been part of the same string of robberies, but he was acquitted.Following his conviction, Geter’s legal representation was taken over by the NAACP. There was a great deal of public attention and media focus on Geter’s case, including a feature episode of “60 Minutes.” His new attorneys succeeded in showing that some of the police testimony at trial was false.They also found two new E-Systems employee witnesses who had seen Geter in his office at the time of the robbery. Another person – Jerry Jerome Stepney, who was serving prison time for a different armed robbery – was implicated in the Kentucky Fried Chicken robberies and identified by four of the five eyewitnesses who had previously identified Geter. Stepney, who bore a physical resemblance to Geter, failed a lie detector test with regard to the robbery of the Kentucky Fried Chicken in Balch Springs. Geter’s conviction was overturned and, in December 1983, he was released from prison while awaiting his new trial, which was scheduled to begin on April 9, 1984. Instead of being retried, Geter’s indictment was dismissed on March 26, 1984.Shortly after his release, Geter married his fiancée Marcia. The following year, he filed an $18 million lawsuit for his wrongful conviction against the DA and the police officers and municipalities involved. He received a $50,000 settlement from the City of Greenville.In 1987, the story of Lenell Geter’s wrongful conviction was made into a motion picture called “Guilty of Innocence.” Geter later became a church deacon, author and professional development coach, and he helped to found a nonprofit organization called Justice Denied Research Inc.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is a former United States Navy officer, and was the highest-ranking female African American in the U.S.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is a former United States Navy officer, and was the highest-ranking female African American in the U.S. Navy upon her retirement in December 2001. She served as the first female intelligence officer in a Navy aviation squadron in 1973. In 1979, she became the first female and African American instructor at the Armed Forces Air Intelligence Training Center at Lowry Air Force Base, Colorado. In 1989, she became the first female and African American to lead the Intelligence Department for Fleet Air Reconnaissance Squadron in Rota, Spain, the largest Navy aviation squadron.Today in our History – April 1, 1979 – Gail Harris, becomes the U.S. Navy’s first female and African American instructor at the Armed Forces Air Intelligence Training Center at Lowry Air Force Base, Colorado.Harris was born on June 23, 1949, in East Orange, New Jersey, to James and Lena Harris, and was raised in Newark, New Jersey’s inner city along with her brother and sister. After high school Captain Harris received her Bachelor of Arts degree in Political Science from Drew University, in Madison, New Jersey in 1971. In 1983, she earned a master’s degree in International Studies at the University of Denver’s Graduate School of International Studies (now the Josef Korbel School of International Studies), where Condoleezza Rice was a classmate of hers. Harris entered the U.S. Navy on May 16, 1973 and was commissioned through Officer Candidate School, in Newport, Rhode Island. In October 1973 to October 1976, Harris was chosen to be the test case for women in Naval Operational Aviation Squadron, and there, she served as the air intelligence officer for Patrol Squadron 47 at Moffett Field, California, her first assignment. At the end of 1976, she was requested by name to report to Kamiseya, Japan, to the Fleet Ocean Surveillance Information Facility and became the first female and African American female to be designated an Intelligence Watch Specialist in the U.S. Navy, as an Intelligence Watch Officer. In April 1979, Captain Gail Harris became the U.S. Navy’s first female and African American instructor at the Armed Forces Air Intelligence Training Center at Lowry Air Force Base, Colorado. There she built up the U.S. Navy’s first course on ocean surveillance information systems and taught the Anti-Submarine Warfare and Soviet Surface Operations courses. In 1984, Captain Harris was one of the first two women assigned to the Office of Naval Intelligence’s War Gaming Team Detachment at the Naval War College, and was chosen to be commander of the Soviet Union’s Theater military forces, twice during the Global War Games. In 1988, Gail was requested by name to coordinate the Defense Department’s Intelligence support for the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, South Korea. In 1989, she was selected to head the Intelligence Department for Fleet Air Reconnaissance Squadron Two, in Rota, Spain, becoming the first female and African American to do so in the U.S. Navy’s largest Aviation Squadron. The mission was for the squadron to support U.S. military and aircraft carrier operations with intelligence reports during the Gulf War.During her service, between 1992 and 1996, in the Middle East, as the intelligence planner for Commander U.S. Forces Central Command, she also headed the U.S. Navy’s Iraqi Crisis Action Cell and Intelligence Watch Center during crisis operations in the Persian Gulf. At this time, she was also specifically chosen by the director of Naval Intellignce and commander of U.S. Naval Forces Central Command to fill in as acting naval attache, Egypt, for a five-month period, becoming the first female attache to a Middle Eastern country. For her last assignment, Harris was selected to develop intelligence policy for computer network defense and computer network attack for the Department of Defense. Since retiring from the military in 2001, Harris worked for Lockheed Martin as an intelligence subject matter expert. She has also been a contributing author to books such as Wake Up and Live Your Life With Passion, and Lies and Limericks: Inspirations from Ireland. She is currently finishing her book/memoir War On Any Given Day, and she also has a weekly R&B radio show. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!