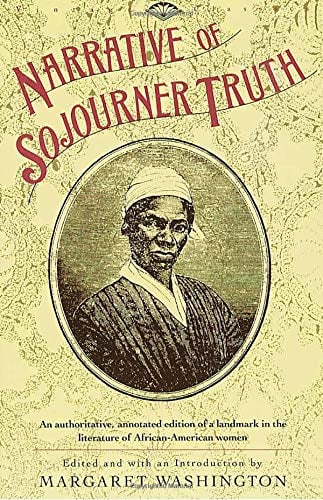

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American abolitionist and women’s rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to freedom in 1826. After going to court to recover her son in 1828, she became the first black woman to win such a case against a white man.She gave herself the name Sojourner Truth in 1843 after she became convinced that God had called her to leave the city and go into the countryside “testifying the hope that was in her”. Her best-known speech was delivered extemporaneously, in 1851, at the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. The speech became widely known during the Civil War by the title “Ain’t I a Woman?”, a variation of the original speech re-written by someone else using a stereotypical Southern dialect, whereas Sojourner Truth was from New York and grew up speaking Dutch as her first language. During the Civil War, Truth helped recruit black troops for the Union Army; after the war, she tried unsuccessfully to secure land grants from the federal government for formerly enslaved people (summarized as the promise of “forty acres and a mule”). She continued to fight on behalf of women and African Americans until her death. As her biographer Nell Irvin Painter wrote, “At a time when most Americans thought of slaves as male and women as white, Truth embodied a fact that still bears repeating: Among the blacks are women; among the women, there are blacks.” A memorial bust of Truth was unveiled in 2009 in Emancipation Hall in the U.S. Capitol Visitor’s Center. She is the first African American woman to have a statue in the Capitol building. In 2014, Truth was included in Smithsonian magazine’s list of the “100 Most Significant Americans of All Time”.Today in our History – November 17, 1787 – Sojourner Truth born Isabella “Belle” Baumfree; c. 1797 – November 26, 1883 was born. Truth was one of the 10 or 12 children born to James and Elizabeth Baumfree (or Bomefree). Colonel Hardenbergh bought James and Elizabeth Baumfree from slave traders and kept their family at his estate in a big hilly area called by the Dutch name Swartekill (just north of present-day Rifton), in the town of Esopus, New York, 95 miles (153 km) north of New York City. Charles Hardenbergh inherited his father’s estate and continued to enslave people as a part of that estate’s property. When Charles Hardenbergh died in 1806, nine-year-old Truth (known as Belle), was sold at an auction with a flock of sheep for $100 to John Neely, near Kingston, New York. Until that time, Truth spoke only Dutch. She later described Neely as cruel and harsh, relating how he beat her daily and once even with a bundle of rods. In 1808 Neely sold her for $105 to tavern keeper Martinus Schryver of Port Ewen, New York, who owned her for 18 months. Schryver then sold Truth in 1810 to John Dumont of West Park, New York. John Dumont was a rapist and considerable tension existed between Truth and Dumont’s wife, Elizabeth Waring Dumont, who harassed her and made her life more difficult. Around 1815, Truth met and fell in love with an enslaved man named Robert from a neighboring farm. Robert’s owner (Charles Catton, Jr., a landscape painter) forbade their relationship; he did not want the people he enslaved to have children with people he was not enslaving, because he would not own the children. One day Robert sneaked over to see Truth. When Catton and his son found him, they savagely beat Robert until Dumont finally intervened. Truth never saw Robert again after that day and he died a few years later. The experience haunted Truth throughout her life.Truth eventually married an older enslaved man named Thomas. She bore five children: James, her firstborn, who died in childhood, Diana (1815), the result of a rape by John Dumont, and Peter (1821), Elizabeth (1825), and Sophia (ca. 1826), all born after she and Thomas united. In 1799, the State of New York began to legislate the abolition of slavery, although the process of emancipating those people enslaved in New York was not complete until July 4, 1827. Dumont had promised to grant Truth her freedom a year before the state emancipation, “if she would do well and be faithful”. However, he changed his mind, claiming a hand injury had made her less productive. She was infuriated but continued working, spinning 100 pounds (45 kg) of wool, to satisfy her sense of obligation to him. Late in 1826, Truth escaped to freedom with her infant daughter, Sophia. She had to leave her other children behind because they were not legally freed in the emancipation order until they had served as bound servants into their twenties. She later said, “I did not run off, for I thought that wicked, but I walked off, believing that to be all right.” She found her way to the home of Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen in New Paltz, who took her and her baby in. Isaac offered to buy her services for the remainder of the year (until the state’s emancipation took effect), which Dumont accepted for $20. She lived there until the New York State Emancipation Act was approved a year later. Truth learned that her son Peter, then five years old, had been sold illegally by Dumont to an owner in Alabama. With the help of the Van Wagenens, she took the issue to court and in 1828, after months of legal proceedings, she got back her son, who had been abused by those who were enslaving him. Truth became one of the first black women to go to court against a white man and win the case. Truth had a life-changing religious experience during her stay with the Van Wagenens and became a devout Christian. In 1829 she moved with her son Peter to New York City, where she worked as a housekeeper for Elijah Pierson, a Christian Evangelist. While in New York, she befriended Mary Simpson, a grocer on John Street who claimed she had once been enslaved by George Washington. They shared an interest in charity for the poor and became intimate friends. In 1832, she met Robert Matthews, also known as Prophet Matthias, and went to work for him as a housekeeper at the Matthias Kingdom communal colony. Elijah Pierson died, and Robert Matthews and Truth were accused of stealing from and poisoning him. Both were acquitted of the murder, though Matthews was convicted of lesser crimes, served time, and moved west. In 1839, Truth’s son Peter took a job on a whaling ship called the Zone of Nantucket. From 1840 to 1841, she received three letters from him, though in his third letter he told her he had sent five. Peter said he also never received any of her letters. When the ship returned to port in 1842, Peter was not on board and Truth never heard from him again. In 1851, Truth joined George Thompson, an abolitionist and speaker, on a lecture tour through central and western New York State. In May, she attended the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, where she delivered her famous extemporaneous speech on women’s rights, later known as “Ain’t I a Woman?”.Her speech demanded equal human rights for all women. She also spoke as a former enslaved woman, combining calls for abolitionism with women’s rights, and drawing from her strength as a laborer to make her equal rights claims.The convention was organized by Hannah Tracy and Frances Dana Barker Gage, who both were present when Truth spoke. Different versions of Truth’s words have been recorded, with the first one published a month later in the Anti-Slavery Bugle by Rev. Marius Robinson, the newspaper owner and editor who was in the audience. Robinson’s recounting of the speech included no instance of the question “Ain’t I a Woman?” Noraid any of the other newspapers reporting of her speech at the time. Twelve years later, in May 1863, Gage published another, very different, version. In it, Truth’s speech pattern appeared to have characteristics of Southern slaves, and the speech was vastly different than the one Robinson had reported. Gage’s version of the speech became the most widely circulated version, and is known as “Ain’t I a Woman?” because that question was repeated four times. It is highly unlikely that Truth’s own speech pattern was Southern in nature, as she was born and raised in New York, and she spoke only upper New York State low-Dutch until she was nine years old. In the version recorded by Rev. Marius Robinson, Truth said:I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights. I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal. I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as any man that is now. As for intellect, all I can say is, if a woman have a pint, and a man a quart – why can’t she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much, – for we can’t take more than our pint’ll hold. The poor men seems to be all in confusion, and don’t know what to do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights, give it to her and you will feel better. You will have your own rights, and they won’t be so much trouble. I can’t read, but I can hear. I have heard the Bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin. Well, if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again. The Lady has spoken about Jesus, how he never spurned woman from him, and she was right. When Lazarus died, Mary and Martha came to him with faith and love and besought him to raise their brother. And Jesus wept and Lazarus came forth. And how came Jesus into the world? Through God who created him and the woman who bore him. Man, where was your part? But the women are coming up blessed be God and a few of the men are coming up with them. But man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, he is surely between a hawk and a buzzard.In contrast to Robinson’s report, Gage’s 1863 version included Truth saying her 13 children were sold away from her into slavery. Truth is widely believed to have had five children, with one sold away, and was never known to boast more children. Gage’s 1863 recollection of the convention conflicts with her own report directly after the convention: Gage wrote in 1851 that Akron in general and the press, in particular, were largely friendly to the woman’s rights convention, but in 1863 she wrote that the convention leaders were fearful of the “mobbish” opponents. Other eyewitness reports of Truth’s speech told a calm story, one where all faces were “beaming with joyous gladness” at the session where Truth spoke; that not “one discordant note” interrupted the harmony of the proceedings. In contemporary reports, Truth was warmly received by the convention-goers, the majority of whom were long-standing abolitionists, friendly to progressive ideas of race and civil rights. In Gage’s 1863 version, Truth was met with hisses, with voices calling to prevent her from speaking. Other interracial gatherings of black and white abolitionist women had in fact been met with violence, including the burning of Pennsylvania Hall.According to Frances Gage’s recount in 1863, Truth argued, “That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody helps me any best place. And ain’t I a woman?” Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman” showed the lack of recognition that black women received during this time and whose lack of recognition will continue to be seen long after her time. “Black women, of course, were virtually invisible within the protracted campaign for woman suffrage”, wrote Angela Davis, supporting Truth’s argument that nobody gives her “any best place”; and not just her, but black women in general. Over the next 10 years, Truth spoke before dozens, perhaps hundreds, of audiences. From 1851 to 1853, Truth worked with Marius Robinson, the editor of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Bugle, and traveled around that state speaking. In 1853, she spoke at a suffragist “mob convention” at the Broadway Tabernacle in New York City; that year she also met Harriet Beecher Stowe. In 1856, she traveled to Battle Creek, Michigan, to speak to a group called the “Friends of Human Progress”.Truth was cared for by two of her daughters in the last years of her life. Several days before Sojourner Truth died, a reporter came from the Grand Rapids Eagle to interview her. “Her face was drawn and emaciated and she was apparently suffering great pain. Her eyes were very bright and mind alert although it was difficult for her to talk.” Truth died early in the morning on November 26, 1883, at her Battle Creek home. On November 28, 1883, her funeral was held at the Congregational-Presbyterian Church officiated by its pastor, the Reverend Reed Stuart. Some of the prominent citizens of Battle Creek acted as pall-bearers; nearly one thousand people attended the service. Truth was buried in the city’s Oak Hill Cemetery. Frederick Douglass offered a eulogy for her in Washington, D.C. “Venerable for age, distinguished for insight into human nature, remarkable for independence and courageous self-assertion, devoted to the welfare of her race, she has been for the last forty years an object of respect and admiration to social reformers everywhere.” Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

Category: Brandon Hardison

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American civil rights leader, activist, ordained minister, businessman, philanthropist, scientist, and politician.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American civil rights leader, activist, ordained minister, businessman, philanthropist, scientist, and politician. He may be best known as a trusted member of fellow famed civil rights activist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Martin Luther King Jr.’s inner circle.Under the banner of their flagship organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, King depended on him to organize and stir masses of people into nonviolent direct action in myriad protest campaigns they waged against racial, political, economic, and social injustice.King alternately referred to him, his chief field lieutenant, as his “bull in a china closet” and his “Castro.” Vowing to continue King’s work for the poor, he is well known in his own right as the founding president of one of the largest social services organizations in North America, His Feed the Hungry and Homeless. His famous motto was “Unbought and Unbossed.”Today in our History – November 16, 200 – Hosea Lorenzo Williams (January 5, 1926 – November 16, 2000) died.Williams was born in Attapulgus, Georgia, a small city in the far southwest corner of the state in Decatur County. Both of his parents were teenagers committed to a trade institute for the blind in Macon.His mother ran away from the institute upon learning of her pregnancy. At the age of 28, Williams stumbled upon his birth father, “Blind” Willie Wiggins, by accident in Florida. His mother died during childbirth when he was 10 years old.He and his older sister, Theresa, were raised by his mother’s parents, Lelar and Turner Williams. Williams was run out of town by a lynch mob at the age of 13 for allegedly consorting with a white girl.Williams served with the United States Army during World War II in an all-African-American unit under General George S. Patton, Jr. and advanced to the rank of Staff Sergeant. He was the only survivor of a Nazi bombing, which left him in a hospital in Europe for more than a year and earned him a Purple Heart.Upon his return home from the war, Williams was savagely beaten by a group of angry whites at a bus station for drinking from a water fountain marked “Whites Only.” He was beaten so badly that the attackers thought he was dead. They called a black funeral home in the area to pick up the body.En route to the funeral home, the hearse driver noticed Williams had a faint pulse and was barely breathing, but was still alive. There were no hospitals in the area that would serve blacks, even in the case of a medical emergency; the trip to the nearest veterans’ hospital was well over a hundred miles. Williams spent more than a month hospitalized recuperating from injuries sustained in the attack.Of the attack, Williams was quoted as saying, “I was deemed 100 percent disabled by the military and required a cane to walk. My wounds had earned me a Purple Heart. The war had just ended and I was still in my uniform for god’s sake! But on my way home, to the brink of death, they beat me like a common dog.The very same people whose freedoms and liberties I had fought and suffered to secure in the horrors of war … they beat me like a dog … merely because I wanted a drink of water.” He went on to say, “I had watched my best buddies tortured, murdered, and bodies blown to pieces. The French battlefields had literally been stained with my blood and fertilized with the rot of my loins.So at that moment, I truly felt as if I had fought on the wrong side. Then, and not until then, did I realize why God, time after time, had taken me to death’s door, then spared my life … to be a general in the war for human rights and personal dignity.” After the war, he earned a high school diploma at the age of 23, then a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree (both in chemistry) from Atlanta’s Morris Brown College and Atlanta University (present-day Clark Atlanta University). Williams was a member of Phi Beta Sigma fraternity.Williams’ birthday coincided with the anniversary of the death of one of that organization’s most prominent members, George Washington Carver. After college, Williams worked for the United States Department of Agriculture as a research scientist.Williams first joined the NAACP, but later became a leader in the SCLC along with Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy, James Bevel, Joseph Lowery, and Andrew Young, among many others. He played an important role in the demonstrations in St. Augustine, Florida, that some claim led to the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964.While organizing during the 1965 Selma Voting Rights Movement he also led the first attempt at a 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, and was tear gassed and beaten severely. On March 7, 1965 – a day that would become known as “Bloody Sunday” – Williams and fellow activist John Lewis led over 600 marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama.At the end of the bridge, they were met by Alabama State Troopers who ordered them to disperse. When the marchers stopped to pray, the police discharged tear gas and mounted troopers charged the demonstrators, beating them with night sticks. Repercussions from the “Bloody Sunday” attempt led to the other great legislative accomplishment of the movement, the Voting Rights Act of 1965.After leaving the SCLC, Williams played an active role in supporting strikes in the Atlanta, Georgia, area by black workers who had first been hired because of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.In the 1966 gubernatorial race, Williams opposed both the Democratic nominee, segregationist Lester Maddox, and the Republican choice, U.S. Representative Howard Callaway. He challenged Callaway on myriad issues relating to civil rights, minimum wage, federal aid to education, urban renewal, and indigent medical care.Williams claimed that Callaway had purchased the endorsement of the Atlanta Journal. Ultimately, after a general election deadlock, Maddox was elected governor by the state legislature.In 1972, Williams ran in the Democratic primary for the U.S. Senate seat formerly held by the late Richard Russell, Jr. He polled 46,153 votes (6.4 percent). The nomination and the election went to fellow Democrat Sam Nunn. In 1974, Williams was elected to the Georgia Senate where he served five terms as a Democrat, until 1984.In 1985 he was elected to the Atlanta City Council, serving for five years, until his election in 1989 when he ran for Mayor of Atlanta but lost to Maynard Jackson. That same year Williams successfully campaigned for a seat on the DeKalb County, Georgia County Commission which he held until 1994.Williams supported former Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter for president in 1976, but surprised many black civil rights figures in 1980 by joining Ralph Abernathy and Charles Evers in endorsing Ronald Reagan. By 1984, however, he had soured on Reagan’s policies, and returned to the Democrats to support Walter F. Mondale.On January 17, 1987, Williams led a “March Against Fear and Intimidation” in Forsyth County, Georgia, which at the time (before becoming a major exurb of northern metro Atlanta) had no non-white residents.The ninety marchers were assaulted with stones and other objects by several hundred counter-demonstrators led by the Nationalist Movement and Ku Klux Klan. The following week 20,000, including senior civil rights leaders and government officials marched. Forsyth County began to slowly integrate in the following years with the expansion of the Atlanta suburbs. In 1971, Hosea Williams founded a non-profit foundation, Hosea Feed the Hungry and Homeless, widely known in Atlanta for providing hot meals, haircuts, clothing, and other services for the needy on Thanksgiving, Christmas, Martin Luther King Jr. Day and Easter Sunday each year. Williams’ daughter Elizabeth Omilami serves as head of the foundation.In 1974, Williams organized the International Wrestling League (IWL), based in Atlanta, with Thunderbolt Patterson serving as president. Among other entrepreneurial endeavors, he founded Hosea Williams Bail Bonds Inc, a bail bond agency located in Decatur, Ga.In early 1951, Williams married Juanita Terry (1925–2000). Together, Williams and Terry had eight children. Four sons: Hosea L. Williams, II (1955–1998), Andre Williams, Torrey Williams, and Hyron Williams, and four daughters: Barbara Williams–Emerson, Elizabeth Williams–Omilami, Yolanda Williams–Favors, and Jaunita Collier. Williams died at Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta, after a three-year battle with cancer on November 16, 2000.Funeral services were held at the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, where close friend Martin Luther King Jr., was once the co-pastor. Williams was preceded in death by his wife three months prior and by his son Hosea II two years earlier. Williams is interred at Lincoln Cemetery.Boulevard Drive in the southeastern area of Atlanta was renamed Hosea L Williams Drive shortly before Williams died. Hosea Williams Drive runs by the site of his former home in the East Lake neighborhood at the intersection of Hosea L. Williams Drive and East Lake Drive.Hosea L. Williams Papers are housed at Auburn Avenue Research Library On African American Culture and History in Atlanta. His daughter Elisabeth Omilami also maintains a traveling exhibit of valuable civil rights memorabilia. Williams was portrayed by Wendell Pierce in the 2014 film Selma. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF– Today’s American Champion was an American actor known for numerous film roles, as well as starring in the NBC television series Homicide: Life on the Street (1993–1999) as Lieutenant Al Giardello.

GM – FBF– Today’s American Champion was an American actor known for numerous film roles, as well as starring in the NBC television series Homicide: Life on the Street (1993–1999) as Lieutenant Al Giardello. His films include the science-fiction/horror film Alien (1979), and the Arnold Schwarzenegger science-fiction/action film The Running Man (1987). He portrayed the main villain Dr. Kananga/Mr. Big in the James Bond movie Live and Let Die (1973). He appeared opposite Robert De Niro in the comedy thriller Midnight Run (1988) as FBI Agent Alonzo Mosley.Today in our History – November 15, 1939 – Yaphet Frederick Kotto is born.Kotto was born in New York City. His mother was Gladys Marie, an American nurse and U.S. Army officer of Panamanian and West Indian descent. His father was Avraham Kotto (according to his son, originally named Njoki Manga Bell), a businessman from Cameroon who emigrated to the United States in the 1920s. The couple separated when Kotto was a child, and he was raised by his maternal grandparents. His father was born Jewish and his mother converted to Judaism.By the age of sixteen, Kotto was studying acting at the Actors Mobile Theater Studio, and at 19, he made his professional acting debut in Othello. He was a member of the Actors Studio in New York. Kotto got his start in acting on Broadway, where he appeared in The Great White Hope, among other productions.His film debut was in 1963, aged 23, in an uncredited role in 4 For Texas. He performed in Michael Roemer’s Nothing But a Man (1964) and played a supporting role in the caper film The Thomas Crown Affair (1968). He played John Auston, a confused Marine Lance Corporal, in the 1968 episode, “King of the Hill”, on the first season of Hawaii Five-O.In 1967 he released a single, “Have You Ever Seen The Blues” / “Have You Dug His Scene” (Chisa Records, CH006).In 1973 he landed the role of the James Bond villain Mr. Big in Live and Let Die, as well as roles in Across 110th Street and Truck Turner. Kotto portrayed Idi Amin in the 1977 television film Raid on Entebbe. He starred as an auto worker in the 1978 film Blue Collar.The following year he played Parker in the sci-fi–horror film Alien. He followed with a supporting role in the 1980 prison drama Brubaker. In 1983, he guest-starred as mobster Charlie “East Side Charlie” Struthers in The A-Team episode “The Out-of-Towners”. In 1987, he appeared in the futuristic sci-fi movie The Running Man, and in 1988, in the action-comedy Midnight Run, in which he portrayed Alonzo Moseley, an FBI agent.A memo from Paramount indicates that Kotto was among those being considered for Jean-Luc Picard in Star Trek: The Next Generation, a role which eventually went to Patrick Stewart. Kotto was cast as a religious man living in the southwestern desert country in the 1967 episode, “A Man Called Abraham”, on the syndicated anthology series, Death Valley Days, hosted by Robert Taylor. In the story line, Abraham convinces a killer named Cassidy (Rayford Barnes) that Cassidy can change his heart despite past crimes. When Cassidy is sent to the gallows, Abraham provides spiritual solace. Bing Russell also appeared in this segment.Kotto retired from film acting in the mid-1990s, though had one final film role in Witless Protection (2008). However, he continued to take on television roles. Kotto portrayed Lieutenant Al Giardello in the long-running television series Homicide: Life on the Street.He has written the book Royalty and also wrote scripts for Homicide. In 2014, he voiced “Parker” for the video game Alien: Isolation, reprising the role he played in the movie Alien in 1979.Kotto’s first marriage was to a German immigrant, Rita Ingrid Dittman, whom he married in 1959. They had three children together before divorcing in 1976. Later, Kotto married Toni Pettyjohn, and they also had three children together, before divorcing in 1989. Kotto married his third wife, Tessie Sinahon, who is from the Philippines, in 1998.Kotto said his father “installed Judaism” in him.In 2000, he was living in Marmora, Ontario, Canada.He died on March 15, 2021, at the age of 81 near Manila, Philippines. No cause of death was given. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American former professional basketball player.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American former professional basketball player.Today in our History – November 14, 1968 – Lionel James “L-Train” Simmons is born.Simmons led South Philadelphia High School to a Philadelphia Public League boys’ championship in 1986, getting an MVP award in the process. He was inducted into the Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame in 2008. Simmons was a 6’7″ small forward from La Salle University, where he won the Naismith College Player of the Year and John R. Wooden Award as a senior. Simmons is fourth in all-time NCAA career points with 3,217 and trails only Pete Maravich, Freeman Williams and Chris Clemons. Simmons became the first player in NCAA history to score more than 3,000 points and pull down more than 1,100 rebounds. He holds the NCAA Basketball record for most consecutive games scoring in double figures with 115. He led the Explorers to three straight NCAA Tournament appearances (1988–90). Simmons was Player of the Year in the Metro Atlantic Athletic Conference for three years. He was a four-time First Team All Big 5 selection and won the Robert V. Geasey Trophy as Big 5 MVP three times. During his career, the Explorers had a 100-31 record. Simmons was inducted into the La Salle University Hall of Athletes in 1995. Simmons was inducted into the Big 5 Hall of Fame in 1996. Simmons was selected by the Sacramento Kings with the seventh pick of the 1990 NBA draft. On March 23, 1991, Simmons scored a career-high 42 points in a 95-100 loss to the Phoenix Suns. He was the runner-up to Derrick Coleman for the 1991 NBA Rookie of the Year Award. Simmons was NBA Player of the Week the week after the All-Star break during his rookie season.He played seven seasons for the Kings, scoring 5,833 career points until prematurely retiring in 1997 due to chronic injuries. He managed to earn more than $21 million in an NBA career that lasted seven seasons. Reserach more about this American Champion and share it with your babies. Male it a champion day!

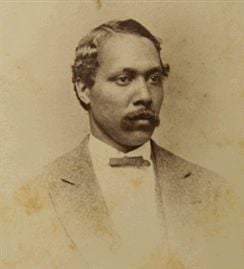

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African American who was appointed United States Ambassador to Haiti in 1869.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African American who was appointed United States Ambassador to Haiti in 1869. He was the first African-American diplomat and the fourth U.S. ambassador to Haiti since the two countries established relations in 1862.His asset was appointed as new leaders emerged among free African Americans after the American Civil War. An educator, abolitionist, and civil rights activist, Bassett was the U.S. diplomatic envoy in 1869 to Haiti, the “Black Republic” of the Western Hemisphere. Through eight years of bloody civil war and coups d’état there, he served in one of the most crucial, but difficult postings of his time. Haiti was of strategic importance in the Caribbean basin for its shipping lanes and as a naval coaling station.Today in our History November 13, 1908 – Prior to his death, Ebenezer D. Bassett returned to live in Philadelphia, where his daughter Charlotte also taught at the ICY. Ebenezer D. Bassett was appointed U.S. Minister Resident to Haiti in 1869, making him the first African American diplomat. For eight years, the educator, abolitionist, and black rights activist oversaw bilateral relations through bloody civil warfare and coups d’état on the island of Hispaniola. Bassett served with distinction, courage, and integrity in one of the most crucial, but difficult postings of his time.Born in Connecticut on October 16, 1833, Ebenezer D. Bassett was the second child of Eben Tobias and Susan Gregory. In a rarity during the mid-1800s, Bassett attended college, becoming the first black student to integrate the Connecticut Normal School in 1853. He then taught in New Haven, befriending the legendary abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Later, he became the principal of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania’s Institute for Colored Youth (ICY).During the Civil War, Bassett became one of the city’s leading voices into the cause behind that conflict, the liberation of four million black slaves and helped recruit African American soldiers for the Union Army. In nominating Bassett to become Minister Resident to Haiti, President Ulysses S. Grant made him one of the highest ranking black members of the United States government.During his tenure the American Minister Resident also dealt with cases of citizen commercial claims, diplomatic immunity for his consular and commercial agents, hurricanes, fires, and numerous tropical diseases.The case that posed the greatest challenge to him, however, was Haitian political refugee General Pierre Boisrond Canal. The general was among the band of young leaders who had successfully ousted the former President Sylvan Salnave from power in 1869. By the time of the subsequent Michel Domingue regime in the mid 1870s Canal had retired to his home outside the capital. Domingue, the new Haitian President, however, brutally hunted down any perceived threat to his power including Canal.General Canal came to Bassett and requested political asylum. A standoff resulted, with Bassett’s home surrounded by over a thousand of Domingue’s soldiers. Finally, after five-month siege of his residence, Bassett negotiated Canal’s safe release for exile in Jamaica.Upon the end of the Grant Administration in 1877, Bassett submitted his resignation as was customary with a change of hands in government. When he returned to the United States, he spent an additional ten years as the Consul General for Haiti in New York City, New York. Prior to this death on November 13, 1908, he returned to live in Philadelphia, where his daughter Charlotte also taught at the ICY. Bassett was 75 at the time of his death.Ebenezer D. Bassett was a role model not simply for his symbolic importance as the first African American diplomat. His concern for human rights, his heroism, and courage in the face of pressure from Haitians, as well as his own capital, place him in the annals of great American diplomats. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a Bahamian-born American entertainer, one of the pre-eminent entertainers of the Vaudeville era and one of the most popular comedians for all audiences of his time

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a Bahamian-born American entertainer, one of the pre-eminent entertainers of the Vaudeville era and one of the most popular comedians for all audiences of his time. He is credited as being the first black man to have the leading role in a film: Darktown Jubilee in 1914.He was by far the best-selling black recording artist before 1920. In 1918, the New York Dramatic Mirror called Williams “one of the great comedians of the world.”Williams was a key figure in the development of African-American entertainment. In an age when racial inequality and stereotyping were commonplace, he became the first black American to take a lead role on the Broadway stage, and did much to push back racial barriers during his three-decade-long career. Fellow vaudevillian W. C. Fields, who appeared in productions with Williams, described him as “the funniest man I ever saw—and the saddest man I ever knew.”Today in our History – November 12, 1874 – Bert Williams (November 12, 1874 – March 4, 1922) was born.Egbert “Bert” Austin Williams was one of the greatest entertainers in America’s history. Born in the Bahamas on November 12, 1874, he came to the United States permanently in 1885.Williams met George Walker in San Francisco in 1893 and the two formed what became the most successful comedy team of their time. After appearing on Broadway in Victor Herbert’s The Gold Bug (1896), Williams and Walker created pioneering vaudeville shows and full musical theater productions, including Senegambian Carnival (1897), The Policy Players (1899), The Sons of Ham (1900), their biggest hit, In Dahomey (1902)–which also played in London the following year, Abyssinia (1906), and Bandana Land (1907).When Walker retired in 1908 due to illness, Williams starred in Mr. Load of Koal (1909)–the last black musical on Broadway for more than ten years. Unable to continue producing shows without Walker, Williams signed on with the Ziegfeld Follies in 1910–the only black performer in this famous review.He explained this controversial move saying, “… colored show business is at a low ebb just now … it was far better to have joined a large white show than to have starred in a colored show, considering conditions.” Williams stayed with the Follies through 1919, after which he appeared with Eddie Cantor in Broadway Brevities (1920) and Under the Bamboo Tree (1921-22). While on tour with the latter show, his failing health caught up with him and he contracted pneumonia. Williams died in New York City on March 4, 1922.Williams was also one of the most prolific black performers on recordings, making around 80 recordings from 1901-22. Indeed, his first recording sessions with George Walker for the Victor Company in 1901 are considered the first recordings by black performers for a major recording company. Williams signed with Columbia in 1906 and the majority of his recordings were with that company, including what became his signature number, “Nobody,” with words written by Alex Rogers. Research more about this great American Champion snd share it with you babies, Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a veteran of WW 1, the war to end all wars. He came back from France to America only to discover that an army uniform worn by a black man meant nothing to a large majority of people in this country.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a veteran of WW 1, the war to end all wars. He came back from France to America only to discover that an army uniform worn by a black man meant nothing to a large majority of people in this country. Today in our History – November 11, 1918 – Charles Lewis was glad to be home.One hundred years ago on Nov. 11, a date now commemorated as Veteran’s Day — which will be observed on Thursday, Nov. 11, in 2021 — the Great War came to an end. Lewis was one of 380,000 black soldiers who had served in the United States army during the World War. A little over a month later, Lewis, after being discharged from Camp Sherman in Ohio, was back in his small town of Tyler Station, Ky.On the night of Dec. 15, a police officer stormed into Lewis’ shack, accusing him of robbery. Lewis, wearing his uniform and claiming the rights of a soldier, resisted arrest and fled. He was soon captured and jailed in nearby Hickman, but by challenging white authority a line had been crossed. Local whites were determined to teach Lewis and other black people a lesson.Around midnight, a mob of approximately 100 masked men stormed the jail. They pulled Lewis out of his cell, tied a rope around his neck and hung him from a nearby tree. As the sun rose the next morning, crowds gathered to view Lewis’ lynched body.While combat in France may have concluded with the armistice, for African Americans, the war continued. World War I transformed America and, through the demands of patriotism, brought the nation together in unprecedented ways. But these demands also exposed deep tensions and contradictions, most vividly in regard to race. African Americans fought a war within the war, as white supremacy proved to be harder to defeat than the German army was.Black people emerged from the war bloodied and scarred. Nevertheless, the war marked a turning point in their struggles for freedom and equal rights that would continue throughout the 20th century and into the 21st.In his April 2, 1917, war declaration address before Congress, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed, “The world must be made safe for democracy.” With this evocative phrase, Wilson framed the purpose and higher cause of American participation in the war. The United States had no selfish aims and, true to its creed, would fight only to ensure that the principles of democracy become enshrined on a global level.Black people immediately recognized the hypocrisy of Wilson’s words. On the eve of American entry into the war, democracy was a distant reality for African Americans. Disfranchisement, segregation, debt peonage and racial violence rendered most black people citizens in name only. A. Philip Randolph, a young socialist and editor of the radical black newspaper The Messenger, spoke for many African Americans when he wrote, “We would rather make Georgia safe for the Negro.”Nevertheless, the majority of African Americans embraced their civic and patriotic duty to support the war effort. Black people had fought heroically in every war since the American Revolution, and they would do so again. By demonstrating their loyalty to the nation as soldiers and civilians, African Americans believed they would be rewarded with greater civil rights.White supremacy tested the patriotism of African Americans throughout the war. Racial violence worsened, the most horrific example being a massacre that took place in July 1917 in East St. Louis that left over one hundred black people dead and entire neighborhoods reduced to ashes.Black soldiers also had a trying experience. The army remained rigidly segregated and the War Department relegated the majority of black troops to labor duties. Black combat soldiers fought with dignity, but still had to confront systemic racial discrimination and slander from their fellow white soldiers and officers.With the armistice, African Americans fully expected that their service and sacrifice would be recognized. They had labored and shed blood for democracy abroad and now expected full democracy at home.The death of Charles Lewis was the first ominous warning that this would not be the case.As a New York newspaper wrote after the lynching, “And the point is made that every loyal American negro who has served with the colors may fairly ask: ‘Is this our reward for what we have done?’”In the months following the armistice, racial tensions across the country increased. Black soldiers returned to their homes eager to resume their lives, but also possessing a deeper appreciation of their social and political rights. Many white Americans, both North and South, worried what this would mean for a tenuous racial status quo that was based on black people remaining subservient and knowing their place.These fears translated into violence.Throughout the summer of 1919, race riots erupted across the country, most notably in Washington, D.C., and Chicago. In Elaine, Ark., an effort by black sharecroppers to organize for better wages enraged local whites and led to a massacre that left upwards to 200 African Americans dead. The number of lynchings of black Americans skyrocketed to 76 by the end of the year, with several black veterans, some still in uniform, amongst the victims. The famed author, diplomat and civil rights leader James Weldon Johnson named these bloody months of 1919 the “Red Summer.”Despite this vicious backlash, African Americans did not surrender. The war had changed African Americans and they remained determined to make democracy in the United States a reality. A generation of “New Negroes,” infused with a stronger racial and political consciousness, would continue the fight for civil rights and lay the groundwork for future generations. They took the words of W. E. B. Du Bois to heart, when he wrote in the May 1919 editorial “Returning Soldiers”:“We return.We return from fighting.We return fighting.Make war for democracy. We saved it in France, and by the Great Jehovah, we will save it in the United States of America, or know the reason why.”A century after the armistice, African Americans, whether in the military, the halls of Congress or in local communities, continue to stand on the front lines in the fight to make democracy a reality in the United States. The lessons of World War I remain relevant today, as we still struggle to know the reason why. Research more about this great American tragity and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion had a varied communications career that took him from the East Coast to the West Coast and back again and led to his history-making appointment in 1960 as the first African American associate press secretary to the president of the United States.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion had a varied communications career that took him from the East Coast to the West Coast and back again and led to his history-making appointment in 1960 as the first African American associate press secretary to the president of the United States.His service during the administrations of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson made him a participant in, as well as eyewitness to, the internal operations of the executive branch of government during a decade of great changes and upheavals in America and the world.Today in our History – November 10, 1960 – Andrew Hatcher was appointed as White House associate press secretary for President John F. Kennedy.Andrew T. Hatcher was born on June 19, 1923 in Princeton, New Jersey. As a youngster he attended the Witherspoon School for Colored Children, an educational institution founded by Betsy Stockton, a former slave, as early as 1830 in connection with the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church. The school and church were located in the section of Princeton nicknamed African Lane for its concentration of black residents.Hatcher went on to Princeton High School, where he graduated in 1941. He continued his education at Springfield College in Massachusetts, beginning in September 1941. After the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 brought the United States into World War II, Hatcher interrupted his college studies to join the U.S. Army in November 1943.During most of the war years Hatcher was stationed at Camp Lee, Virginia, where he received basic and branch training. He also participated in the Officer Candidate School (OCS) at Camp Lee and was eventually promoted to the rank of second lieutenant. Hatcher also served at the Oakland Army Base in northern California and remained there until he received his honorable discharge in June 1946 after nearly three years of active duty.Hatcher returned to Springfield College in September 1946 and was noted in the school’s 1947 yearbook as the editor of The Student, the college newspaper. As a former soldier and military officer who was a few years older than the typical college student, Hatcher was a “non-traditional student” as well as a member of a racial minority on campus. It is unclear if Hatcher graduated from Springfield, but sources indicate that in later years he served as a member of the college’s alumni council.Hatcher made the decision to return to the northern California area and became a journalist for the San Francisco Sun-Reporter, an African American newspaper. He also attended the Golden Gate Law School between 1952 and 1954, but it is unclear whether he received a degree, as available sources do not indicate that Hatcher ever actively pursued the practice of law.Hatcher soon made the transition from journalism to politics and became actively involved with the Democratic Party. As a result, he received a political appointment in 1959 as assistant secretary of labor in the administration of California governor Edmund G. “Pat” Brown.Hatcher’s abilities did not go unnoticed by other leading Democrats, and he became a speechwriter for New York governor Adlai Stevenson during his two unsuccessful campaigns for president during the 1950s.Along with his close friend Pierre Salinger, Hatcher joined the presidential campaign of Massachusetts senator John F. Kennedy in 1960 as a speechwriter and member of the campaign press staff. By this time Hatcher was a veteran of the campaign trail and helped considerably with the numerous details and logistics involved in presentations by the candidate around the country.His presence on the team also helped Kennedy in his efforts to appeal to African American voters in particular, whose support provided the margin of victory over vice president Richard M. Nixon in the closely contested election.One of Kennedy’s first appointments after winning the presidency was his selection of Hatcher as White House associate press secretary on November 10, 1960. Salinger had been appointed to the President’s cabinet as press secretary, so the two friends and colleagues were able to continue to work as a team during the Kennedy administration.Hatcher was the first African American to serve in such a high-ranking position, being involved in the inner workings of the executive branch on a daily basis. The symbolic importance of this achievement was underscored when television cameras showed only Salinger and Hatcher seated behind the president during his first news conference after taking office in January 1961.He died on July 26, 1990 and is interred in Suffolk County, New York. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African-American freed slave from Tennessee who became one of the leading manufacturers of wagons for the Oregon Trail.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African-American freed slave from Tennessee who became one of the leading manufacturers of wagons for the Oregon Trail. In the mid-19th century, his business was located at the eastern origin of the trail in Independence, Missouri, serving westward pioneers including the Forty-niners. He was called the “only colored man in the manufacturing business” and Kansas City’s first “Colored Man of Means”.He worked to free slaves, specifically purchasing them in order to preserve their families intact and then paying them wages to buy their emancipation. Though living through the American Civil War and racial segregation, he was widely respected in white society, having financed or co-signed on many of their businesses. He received generous community support when his business burned down twice, and his grave is conspicuously located among those of white people.The Kansas City Star extensively eulogized him 26 years after his death, saying “This negro fought valiantly for freedom and respectability”.Today in our History – November 9, 1812 – Hiram Young (November 9, 1812—January 22, 1882) was born.Young was enslaved from birth in Tennessee on November 9, 1812. Little is known about the enslaved period of his life beyond the fact that he married Matilda Huederson. Living in Independence, Missouri in the 1840s, the easygoing slaveowner, Judge Sawyer, allowed many privileges and paid Young a wage he kept, for extra work during his spare time. Young approached Sawyer to purchase emancipation. How much money do you want fo’ me, Marse Judge? … I’ve been talkin’ about buyin’ myself, Marse Judge. I allus wanted to own a nigga, Marse Judge, and I’se do mos’ likely one on the place. I don’t reckon how you could take dat $1,200 ob mine an’ let me pay de balance as we go ‘long? Sawyer declared a price of US$2,500 (equivalent to about $65,000 in 2020) with a down payment of $1,200, issued freedom papers, and Young “gave a mortgage on himself for $1,300”. At some point, he bought his wife’s freedom for $800 (equivalent to about $12,200 in 2020), likely before buying his own. According to the law, any child born to an African-American couple, in which one is free and the other is enslaved, inherits the status of the mother. Upon gaining his freedom, with Matilda and their daughter Amanda Jane, born 1849, he moved to Independence, Missouri around 1850. He also bought a slave woman, only referred to as “the Kentucky girl” and the “absolute love of his life”, for whom he paid $1,600 (equivalent to about $50,000 in 2020). The St. Louis Daily Globe described this as an “exorbitant amount, especially for a female slave”—double what he paid for his own wife. Young did not legally buy her freedom, as the Globe reports he never did “relinquish his right to her as chattel”. She was sent away for education in a seminary, returning to become the house maid at the Young plantation home. This arrangement made “domestic life anything but peaceful”, and he retained her ownership until the abolition of slavery. Further it states he sought divorce to Matilda but found “divorce court was not at that time either popular or convenient”. He and the Kentucky slave had several daughters, unnamed by the Globe, all of whom Young provided with an education. After the first of two devastating fires that ruined his uninsured business, he raised money by selling his wife and daughter back into slavery to a kind former master, Judge Sawyer, according to the Kansas City Star’s recollection in 1890. It is not clarified, however, if this means advanced pay for future labor, or completely enslaving them again.As his influence in the community grew, he and Matilda became founding members of the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal church in 1866 in Independence. In 1877 the church was moved to a new location, where it still operates today. Young contributed greatly to the building of the new church. He helped the fundraising and opening of what was, for decades, the only school for African-American children in Independence. Originally it was named after activist Frederick Douglass. The 1850 census lists Young as a man simply with a trade skill, though, not as mulatto or black, and notably as having no property or personal wealth. By 1851, according to his own words he had “set himself up in the manufactory of yokes and wagons—principally freight wagons for hauling government freight across the plains”. He reportedly “was a skillful worker in wood and could make anything, from an axe helve to a wagon”.Young also owned a home and plantation, complete with slaves who “both hated and feared him, for he was not the kindest of task masters and knew to a row of corn how much each slave should do as a day’s labor”. Extending his path of freedom to others, Young allowed his slaves to work for wages they kept to buy their emancipation. Only a few days after his death, the Wyandotte Gazette states that, “Before the war he, though himself a negro, owned slaves, among whom were Riley Young, his own brother, old aunt Lucy Jones, Wesley Cunningham, and others well known in Wyandotte.” The US Census of 1860 reports he was completing thousands of ox yokes and 800 to 900 wagons a year. He employed approximately 50 to 60 men between his shop on Liberty Street and his 480-acre farm east of Independence in the Little Blue Valley. Employing around 20 men, Young’s shop utilized a four-horsepower steam engine, nearly unheard of at the time, along with seven forges running non-stop. Census officials also noted 300 completed wagons worth $48,000 and 6,000 yokes worth $13,500. The business’s inventory alone was appraised at more than $50,000 (equivalent to about $1,440,000 in 2020). Young managed to prosper through the border wars of Kansas and Missouri while many other businesses were destroyed or went bankrupt. The beginning of the American Civil War created a dangerous living situation for Young’s family. The Kansas City Journal later recalled his property being looted by Civil War troops: “He managed a fine farm, had many wagons in his shop, and was comfortably fixed for life. But federal troops passed his way and he was fine picking for the men of war.” The family relocated to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas in 1862 or 1863. There he set up his business and added a service of filling list of supplies for those traveling, especially hastily. The Wyandotte Gazette says that during the war, Young’s “colored friends entrusted him with their surplus money. He failed under that burden of responsibility.” The paper summarized his notorious success: “his goods are scattered from Texas to British Columbia and from the Mississippi to the Pacific Coast”.After the Civil War, 1868 brought Young and his family back to Independence, where he re-established his business. However, the rise of steam locomotive trains largely obsoleted westward wagons so he reshaped his business as a planing mill. April 22, 1873 brought a second fire to his business. This time it was insured for $2,500, though the damages cost $6,000 (equivalent to about $130,000 in 2020). His plight was embraced by a community campaign to purchase an engine to “assist in the speedy re-establishment of his factory”. The St. Joseph Daily Gazette lauded this solidarity as “only right”, admonishing the Independence city government to echo other cities’ past donations of untaxed land for the benefit of other “factories not so beneficial to a community as Young’s”. In 1877, he was heralded by the Kansas City Journal of Commerce as the “only colored man in the manufacturing business”.In 1879, Young launched a lawsuit against the United States government for wartime property damages, in amounts progressively increasing to $22,100 (equivalent to about $614,000 in 2020). The lawsuit continued fruitlessly even after his death, through various committees, additional testimonies, and congressional bills, until it was thrown out in 1907.By 1880 the mill had a twelve horse-power engine and the annual payroll was more than $60,000 (equivalent to about $1,609,000 in 2020). He never again reached the success of his wagon manufacturing company of pre-war years, which a study in 1973 found to have been “56 times more wealthy than the average citizen of the county”.Attempting to rebuild his business to its pre-war lucrative levels, Young died January 22, 1882, cash poor, though the estate was worth $50,000 (equivalent to about $1,440,000 in 2020). His grave is at Woodlawn Cemetery in Independence, Missouri. His wife opened a new lawsuit after his death for government reparations of losses in war. She hoped to pass the sizable reward to their daughter Amanda Jane. This claim included 7,000 bushels of corn and 37 wagons, worth a total of $10,750 plus twenty years worth of appreciation the case had been ignored in the court system. In 1908, the Kansas City Star extensively eulogized Young 26 years after his death, saying “This negro fought valiantly for freedom and respectability” and that his gravestone “perpetuates the memory of the most widely and favorably known negro of that city—one who filled a responsible position in business life for many years, and died highly respected by whites and blacks alike … his monument stands not in the portion of the cemetery commonly used by colored people, but in a conspicuous lot among white people—a very remarkable thing for Independence”.Upon Young’s death in 1882, the school that he’d helped found in Independence was renamed from Frederick Douglass school to Hiram Young school. In 2004 it fundraised $650,000 (equivalent to about $891,000 in 2020) for renovations to become a new community center providing services including “vision, hearing, diabetes, and cancer”.In December 1987, the city council of Independence passed a resolution to change the name of Lexington Park to Hiram Young Park, commemorating Young as “one of the wealthiest men in Jackson County in the 1800s”. The park includes a 50 foot wooden wagon wheel recessed into the ground surrounded by flower boxes and benches, and a large stone with a plaque dedicated to Young. The park is bordered by Hiram Young Lane, a renamed portion of Lexington Avenue. McCoy Park in Independence celebrates Young in one of three painted panels by artist Cheryl Harness, with a storybook portrayal of Oregon Trail history. Minor Park of Kansas City, Missouri bears Young’s portrait on a large decorative mural upon the Red Bridge. In 2016, The Telegraph commemorated Black History Month with an article titled “Hiram Young: Kansas City’s First ‘Colored Man of Means'”. The Santa Fe Trail Association said, “His life and career testify to the rich and vital ethnic diversity that made the American West a place of particularly new and exciting possibilities in the 19th century.” Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was was an American dancer, choreographer, and dance teacher.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was was an American dancer, choreographer, and dance teacher. Born in Seattle, she drew on her African-American heritage in her original dance works. American composer John Cage wrote his first piece for prepared piano, Bacchanale (1940), for a dance by Fort. She died from breast cancer at the age of 58.Today in our History – November 8, 1875 – Syvilla Fort (July 3, 1917 – November 8, 1975) was born.Born in Seattle, Washington, Syvilla Fort began studying dance when she was three years old. After she was denied admission to several ballet schools because she was black, Fort’s early dance education took place in her home and in private lessons. By the time she was nine years old, Fort was teaching ballet, tap, and modern dance to small groups of neighborhood children who could not afford private lessons.Fort attended the Cornish School of Allied Arts in Seattle as their first black student after graduating from high school in 1932. After spending five years at the Cornish School, Fort decided to pursue her dance career in Los Angeles, and in 1939 her neighbor, black composer William Grant Still, introduced Fort to dancer Katherine Dunham. Several weeks later, Fort began dancing and touring with the Katherine Dunham Company and learning the Dunham technique, which was rooted in the dance traditions of Africa, Haiti, and Trinidad. Fort danced with the company until 1945 and was included in the well-known film Stormy Weather (1943).While dancing with the Dunham Company, Fort neglected a serious knee injury which prevented her from performing professionally by the mid-1940s. In 1948, Dunham appointed Fort as chief administrator and dance teacher of the Katherine Dunham School of Dance in New York, a position Fort retained until 1954 when the school closed because of financial problems. In 1955, Fort joined her husband Buddy Phillips to open a dance studio on West 44th Street in New York. In this studio Fort developed what she called the “Afro-Modern technique” which fused the Dunham approach with modern styles of dance that Fort learned in her early education. She continued to use this method in her work as a part-time instructor of physical education at Columbia University’s Teachers College from 1967 to 1975.The studio on 44th Street thrived until 1975 when Fort began struggling against breast cancer and was unable to solve the school’s financial problems. Her staff and students found a new studio for Fort on West 23rd Street where she taught through the summer of 1975. Fort shaped three generations of dancers and among her best-known students were Marlon Brando, James Dean, Jane Fonda, James Earl Jones, Eartha Kitt, José Limón, Chita Rivera, and Geoffrey Holder.Five days before her death from breast cancer on November 8, 1975, Fort attended a tribute to her life’s work which was organized by the Black Theater Alliance and hosted by her student Alvin Ailey and by Harry Belafonte.In 1992, Fort’s work was honored again when dancers from several companies performed an evening of her choreography at New York’s Symphony Space.Buddy Phillips’ son Sabur Abdul-Salaam, Syvilla’s stepson, has published a book, Spiritual Journey of An American Muslim, that includes additional information concerning her. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!+3