GM – FBF – Today, I would like to share with you a story about New Jersey’s largest City. The Riots during that summer of 1967 not only hit Newark but from Jersey City down to New Brunswick. I f you lived in Trenton, our city had a few people around town but thank God not as bad as North Jersey.

Remember – ” It was a scene in the old west, people shooting at police and police shooting back” – Mayor Hugh Addonizio of Newark, NJ.

Today in our History – July 12, 1967 – “BURN BABY BURN”

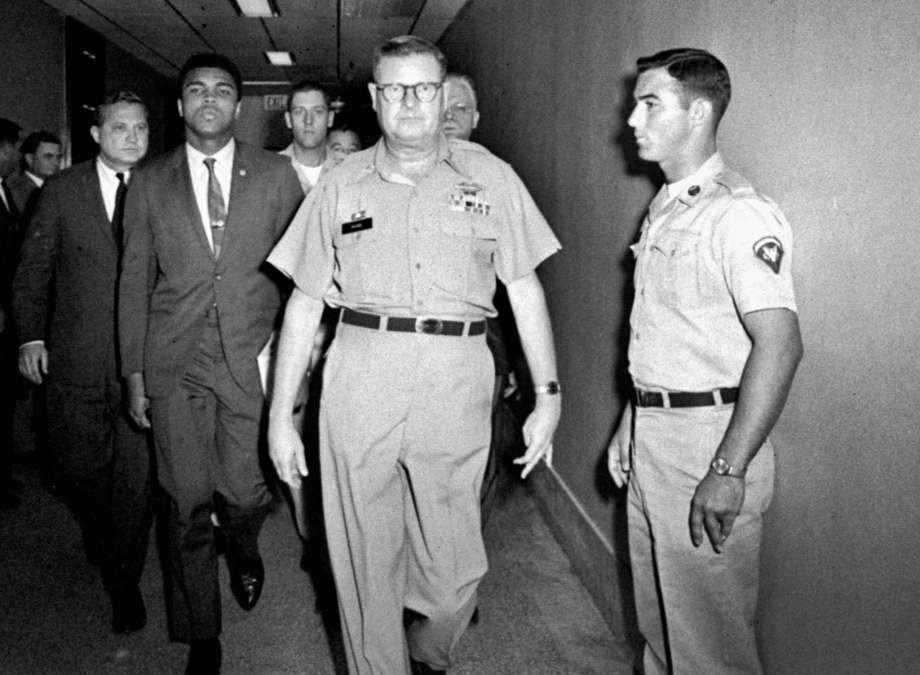

The Newark Riot of 1967 which took place in Newark, New Jersey from July 12 through July 17, 1967, was sparked by a display of police brutality. John Smith, an African American cab driver for the Safety Cab Company, was arrested on Wednesday July 12 when he drove his taxi around a police car and double-parked on 15th Avenue. According to a police report later released to the press, the police claimed that Smith was charged with “tailgating” and driving in the wrong direction on a one-way street. Smith was also charged with using offensive language and physical assault.

A witness who had seen Smith’s arrest called members of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the United Freedom Party, and the Newark Community Union Project. These civil rights leaders were given permission to see Smith in his 4th Precinct holding cell. After noticing his injuries inflicted by the police, they demanded that he be transported to a hospital. Their demands were granted and Smith was moved to Beth Israel Hospital in Newark.

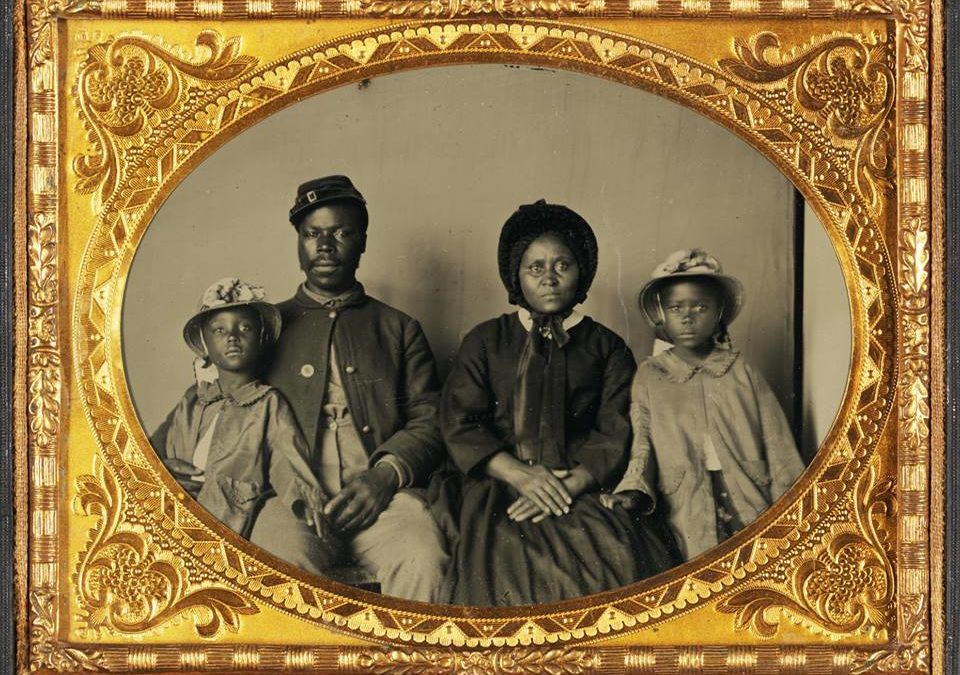

Around 8:00 p.m. black Newark cab drivers began to circulate the report of Smith’s arrest on their radios. Word spread down 17th Avenue, west of the precinct police station where Smith had been held. Residents in this predominantly black city recalled a long history of similar events with the Newark Police. Many of them angrily gathered on the streets facing the 4th Precinct.

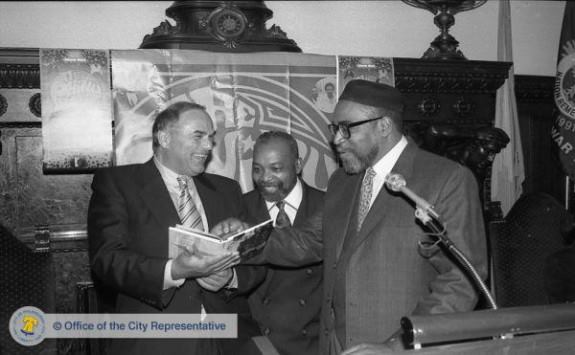

At 11:00 p.m. one of the civil rights leaders informed the police that a peaceful protest would be organized across the street from the precinct. A police officer handed the leader a bullhorn to address the crowd. Bob Curvin, a member of CORE, was joined by Timothy Still, the president of a poverty program, and Oliver Lofton, who was the administrator of the Newark Legal Services Project. Although the three speakers urged a nonviolent protest march, an unidentified local resident took the bullhorn and urged violence. Young men from the neighborhood began to pick up bricks and bottles and searched for gasoline. Shortly afterwards, objects were thrown at the precinct windows.

Shortly after midnight, two Molotov cocktails were thrown at the precinct. Then a group of 25 people on 17th Avenue began to loot stores. The looting drew larger crowds and Newark was now engulfed in rioting.

Despite the violence, on Thursday morning Newark Mayor announced that Wednesday night’s activities were isolated incidents and were not of riot proportions. At 6:00 p.m. Thursday night, a large group of young kids gathered on the street where traffic had been blocked. Word spread along 17th Avenue that people would again demonstrate against the precinct. Human Rights Commission Director James Threatt arrived and told the crowds to disperse. They refused and rioting commenced for a second night.

After midnight Thursday, looting spread throughout the major commercial district of the ghetto in Newark. Groups of young adults smashed windows while chanting “Black Power.” At the same time the looting spread, the police were given clearance to use firearms to defend themselves. At 2:20 a.m. Mayor Addonizio asked New Jersey Governor Richard J. Hughes to send in the National Guard to help in restoring order.

At around 4:00 a.m. a looter was shot while trying to flee from two police officers. By early Friday morning five people had been killed and 425 people were jailed. Hundreds were wounded. More than 3,000 National Guardsmen arrived later in the day along with five hundred state troopers. By mid-afternoon, the Guardsmen and the troopers arrived, formed convoys, and were moving throughout the city.

Despite the presence of National Guardsmen and state troopers rioting continued for three more days. As the riot approached its final hours, 26 people, mostly African Americans, were reported killed, another 750 were injured and over 1,000 were jailed. Property damage exceeded $10 million. The riot, the worst civil disorder in New Jersey history, ended on July 17, 1967. Research more about this wild time in “BRICK CITY” and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!