GM – FBF – Today, I want to share with you a story about a 14

year old young man who was in the wrong place at the wrong time. While visiting

my grandmother in Perry, GA. during those days in the ’50’s and early ’60’s, I

was told to not look at or talk to white people. She always reminded me that

this could happen to you if you act and talk like you do back home in Trenton,

NJ. A sad story that has been given a new Investigation.

Remember – “It never occurred to me that Bobo would be killed

for whistling at a white woman.” — Simeon Wright, Emmett Till’s Cousin

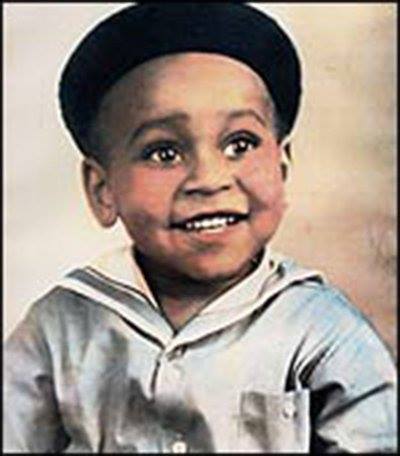

Today in our History – July 25,1941 – Emmit Till wes born.

Emmett Till was born in 1941 in Chicago and grew up in a

middle-class black neighborhood. Till was visiting relatives in Money,

Mississippi, in 1955 when the fourteen-year-old was accused of whistling at

Carolyn Bryant, a white woman who was a cashier at a grocery store.

Four days later, Bryant’s husband Roy and his half-brother J.W.

Milam kidnapped Till, beat him and shot him in the head. The men were tried for

murder, but an all-white, male jury acquitted them.

Till’s murder and open casket funeral galvanized the emerging

civil rights movement. More than six decades later, in January 2017, Timothy

Tyson, author of The Blood of Emmett Till and a senior research scholar at Duke

University, revealed that in a 2007 interview Carolyn admitted to him that she

had lied about Till making advances toward her. The following year, it was

reported that the Justice Department had reopened an investigation into Till’s

murder.

Emmett Louis Till was born on July 25, 1941, in Chicago, the

only child of Louis and Mamie Till. Till never knew his father, a private in

the United States Army during World War II.

Mamie and Louis Till separated in 1942, and three years later,

the family received word from the Army that the soldier had been executed for

“willful misconduct” while serving in Italy.

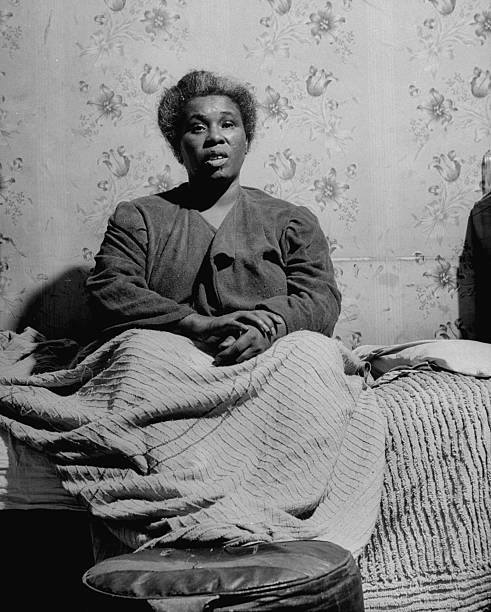

Emmett Till’s mother was, by all accounts, an extraordinary woman. Defying the

social constraints and discrimination she faced as an African-American woman

growing up in the 1920s and ’30s, Mamie Till excelled both academically and

professionally.

She was only the fourth black student to graduate from suburban

Chicago’s predominantly white Argo Community High School, and the first black

student to make the school’s “A” Honor Roll. While raising Emmett

Till as a single mother, she worked long hours for the Air Force as a clerk in

charge of confidential files.

Emmett Till, who went by the nickname Bobo, grew up in a

thriving, middle-class black neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side. The

neighborhood was a haven for black-owned businesses, and the streets he roamed

as a child were lined with black-owned insurance companies, pharmacies and

beauty salons as well as nightclubs that drew the likes of Duke Ellington and

Sarah Vaughan.

Those who knew Till best described him as a responsible, funny

and infectiously high-spirited child. He was stricken with polio at the age of

5, but managed to make a full recovery, save a slight stutter that remained

with him for the rest of his life.

With his mother often working more than 12-hour days, Till took

on his full share of domestic responsibilities from a very young age.

“Emmett had all the house responsibility,” his mother later recalled.

“I mean everything was really on his shoulders, and Emmett took it upon

himself. He told me if I would work, and make the money, he would take care of

everything else. He cleaned, and he cooked quite a bit. And he even took over

the laundry.”

Till attended the all-black McCosh Grammar School. His classmate

and childhood pal, Richard Heard, later recalled, “Emmett was a funny guy

all the time. He had a suitcase of jokes that he liked to tell. He loved to

make people laugh. He was a chubby kid; most of the guys were skinny, but he

didn’t let that stand in his way. He made a lot of friends at McCosh.”

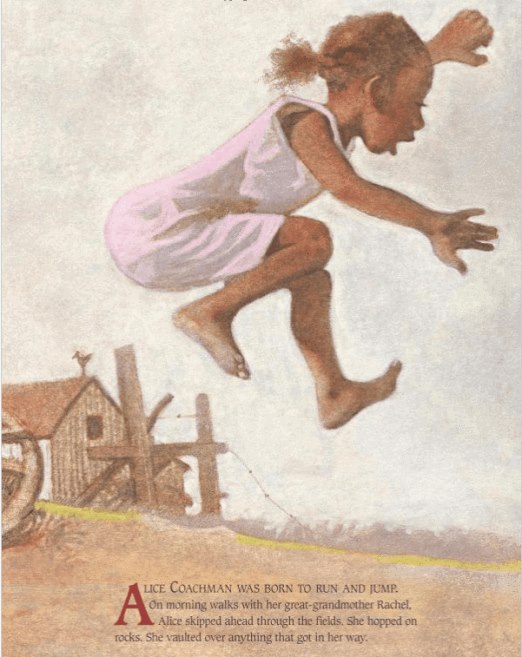

In August 1955, Till’s great uncle, Moses Wright, came up from

Mississippi to visit the family in Chicago. At the end of his stay, Wright was

planning to take Till’s cousin, Wheeler Parker, back to Mississippi with him to

visit relatives down South, and when Till, who was just 14 years old at the

time, learned of these plans, he begged his mother to let him go along.

Initially, Till’s mother was opposed to the idea. She wanted to

take a road trip to Omaha, Nebraska, and tried to convince her son to join her

with the promise of open-road driving lessons.

But Till desperately wanted to spend time with his cousins in Mississippi, and

in a fateful decision that would have grave impact on their lives and the

course of American history, Till’s mother relented and let him go.

On August 19, 1955—the day before Till left with his uncle and

cousin for Mississippi—Mamie Till gave her son his late father’s signet ring,

engraved with the initials “L.T.”

The next day she drove her son to the 63rd Street station in Chicago. They

kissed goodbye, and Till boarded a southbound train headed for Mississippi. It

was the last time they ever saw each other.

Three days after arriving in Money, Mississippi—on August 24,

1955—Emmett Till and a group of teenagers entered Bryant’s Grocery and Meat

Market to buy refreshments after a long day picking cotton in the hot afternoon

sun.

What exactly transpired inside the grocery store that afternoon

will never be known. Till purchased bubble gum, and in later accounts he was

accused of either whistling at, flirting with or touching the hand of the

store’s white female clerk—and wife of the owner—Carolyn Bryant.

Four days later, at approximately 2:30 a.m. on August 28, 1955,

Roy Bryant, Carolyn’s husband, and his half brother J.W. Milam kidnapped Till

from Moses Wright’s home. They then beat the teenager brutally, dragged him to

the bank of the Tallahatchie River, shot him in the head, tied him with barbed

wire to a large metal fan and shoved his mutilated body into the water.

Moses Wright reported Till’s disappearance to the local

authorities, and three days later, his corpse was pulled out of the river.

Till’s face was mutilated beyond recognition, and Wright only managed to

positively identify him by the ring on his finger, engraved with his father’s

initials—”L.T.”

“It never occurred to me that Bobo would be killed for whistling at a white

woman.” — Simeon Wright, Emmett Till’s cousin

“It would appear that the state of Mississippi has decided to maintain white

supremacy by murdering children.” — Roy Wilkins, head of the NAACP.

Till’s body was shipped to Chicago, where his mother opted to

have an open-casket funeral with Till’s body on display for five days. Thousands

of people came to the Roberts Temple Church of God to see the evidence of this

brutal hate crime.

Till’s mother said that, despite the enormous pain it caused her to see her

son’s dead body on display, she opted for an open-casket funeral in an effort

to “let the world see what has happened, because there is no way I could

describe this. And I needed somebody to help me tell what it was like.”

“With his body water-soaked and defaced, most people would

have kept the casket covered. [His mother] let the body be exposed. More than

100,000 people saw his body lying in that casket here in Chicago. That must

have been at that time the largest single civil rights demonstration in

American history.” — Jesse Jackson

The weeks that passed between Till’s burial and the murder and

kidnapping trial of Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, two black publications, Jet

magazine and the Chicago Defender, published graphic images of Till’s corpse.

By the time the trial commenced—on September 19, 1955—Emmett

Till’s murder had become a source of outrage and indignation throughout the

country. Because blacks and women were barred from serving jury duty, Bryant

and Milam were tried before an all-white, all-male jury.

In an act of extraordinary bravery, Moses Wright took the stand

and identified Bryant and Milam as Till’s kidnappers and killers. At the time,

it was almost unheard of for blacks to openly accuse whites in court, and by

doing so, Wright put his own life in grave danger.

Despite the overwhelming evidence of the defendants’ guilt and

widespread pleas for justice from outside Mississippi, on September 23, the

panel of white male jurors acquitted Bryant and Milam of all charges. Their

deliberations lasted a mere 67 minutes.

Only a few months later, in January 1956, Bryant and Milam

admitted to committing the crime. Protected by double jeopardy laws, they told

the whole story of how they kidnapped and killed Emmett Till to Look magazine

for $4,000.

“J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant died with Emmett Till’s blood on their

hands,” Simeon Wright, Emmett Till’s cousin and an eyewitness to his

kidnapping (he was with Till the night he was kidnapped by Milam and Bryant),

later stated. “And it looks like everyone else who was involved is going

to do the same. They had a chance to come clean. They will die with Emmett

Till’s blood on their hands.”

I

“I thought about Emmett Till, and I couldn’t go back [to the back of the

bus].” — Rosa Parks

Coming only one year after the Supreme Court’s landmark decision

in Brown v. Board of Education mandated the end of racial segregation in public

schools, Emmett Till’s death provided an important catalyst for the American

civil rights movement.

One hundred days after Till’s murder, Rosa Parks refused to give

up her seat on an Alabama city bus, sparking the yearlong Montgomery Bus

Boycott. Nine years later, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

outlawing many forms of racial discrimination and segregation. In 1965, the

Voting Rights Act, outlawing discriminatory voting practices, was passed.

[Emmett Till’s murder was] one of the most brutal and inhuman

crimes of the 20th century. — Martin Luther King Jr.

Though she never stopped feeling the pain of her son’s death, Mamie Till (who

died of heart failure in 2003) also recognized that what happened to her son helped

open Americans’ eyes to the racial hatred plaguing the country, and in doing so

helped spark a massive protest movement for racial equality and justice.

“People really didn’t know that things this horrible could

take place,” Mamie Till said in an interview with Devery S. Anderson,

author of Emmett Till: The Murder That Shocked the World and Propelled the

Civil Rights Movement, in December 1996. “And the fact that it happened to

a child, that make all the difference in the world.”

Timothy Tyson’s Book and Revived Investigation

Over six decades after Till’s brutal abduction and murder, in January 2017,

Timothy Tyson, author of The Blood of Emmett Till and a senior research scholar

at Duke University, revealed that in a 2007 interview Carolyn Bryant Donham

(she had divorced and remarried) admitted to him that she had lied about Till

making advances toward her.

As of Last Week, July 15,

2018 – the case is re-opened and new Information is being viewed. The Justice

Department declined to comment on Thursday, but it appeared that the government

had chosen to devote new attention to the case after a central witness, Carolyn

Bryant Donham, recanted parts of her account of what transpired in August 1955.

Two men who confessed to killing Emmett, only after they had been acquitted by

an all-white jury in Mississippi, are deadResearch more about this great

American and share with your babies as it was told to me. Make it a champion

day!