GM – FBF – I was in Junior High School (Junior High School #1)

Trenton, NJ. In that school year all 5 Junior High Schools came together and

went undefeated in Mercer County, NJ Footbal, Jr. # 3 defeated Jr. # 1 as we

lost the city Basketball Championship for the first time in 10 years. We also

lost the Baseball Championship to Jr.# 3 but ran away with the City Track

Championship for 15 years going undefeated.With three weeks left until the end

of the school year, as President of the 9th grade class, I still had one last

party to host in our brand new common area named after Thurgood Marshall. I

travled to Harlem, N.Y. and purchased some music (Bootleg out of a car trunk)

of The Last Poets. I got permission of the building Principal and I played

three songs of The Last Poets at the start, middle and end of the dance. Peace

to the words of the Last Poets.

Remember -“There wouldn’t be an America if it wasn’t for

black people. So you have some dedicated black Americans who will die a million

deaths to save America. And this is home for us.” – Abiodun Oyowele

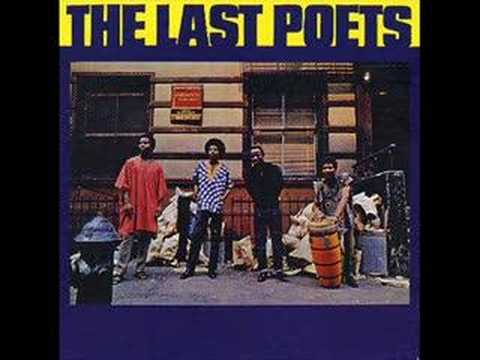

Today in our History – May 19, 1968 – The Original Last Poets

were formed on Malcolm X’s birthday, at Marcus Garvey Park in East Harlem. On

October 24th 1968, the group performed on pioneering New York television

program Soul!.

Luciano, Kain, and Nelson recorded separately as The Original

Last Poets, gaining some renown as the soundtrack artists of the 1971 film

Right On!

In 1972, they appeared on Black Forum Records album Black

Spirits – Festival Of New Black Poets In America with “And See Her Image

In The River” and “Song of Ditla, part II”, recorded live at the

Apollo Theatre, Harlem, New York. A book of the same name was published by

Random House (1972 – ISBN 9780394476209).

The original group actually consisted of Gylan Kain, David

Nelson and Abiodun Oyowele. Nelson left in the fall of 1968 and was replaced by

Felipe Luciano, then Luciano left to start the Young Lords and was replaced by

Alafia Pudim (later known as Jalaluddin Mansur). Following the success of the

reformed Last Poets first album, Luciano, Kain, and Nelson reunited to record

their only album Right On in 1967, the soundtrack to a documentary movie of the

same name that finally saw release in 1971. (See also Performance (1970 film

featuring Mick Jagger) soundtrack song “Wake Up, Niggers”.) The Right

On album was released under the group name The Original Last Poets to

simultaneously establish their primacy and distance themselves from the other

group of the same name.

The Jalal-led group coalesced via a 1969 Harlem writers’

workshop known as East Wind. Jalal Mansur Nuriddin a.k.a. Alafia Pudim, Umar

Bin Hassan, and Abiodun Oyewole, along with poet Sulaiman El-Hadi and

percussionist Nilaja Obabi, are generally considered the best-known members of the

various lineups. Jalal, Umar, and Nilaja appeared on the group’s 1970

self-titled debut LP and follow-up This Is Madness. Nilija then left, and a

third poet, Sulaiman El-Hadi, was added. This Jalal-Sulaiman version of the

group made six albums together but recorded only sporadically without much

promotion after 1977.

Having reached US Top 10 chart success with its debut album, the

Last Poets went on to release the follow-up, This Is Madness, without

then-incarcerated Abiodun Oyewole. The album featured more politically charged

poetry that resulted in the group being listed under the counter-intelligence

program COINTELPRO during the Richard Nixon administration. Hassan left the

group following This Is Madness to be replaced by Sulaiman El-Hadi (now deceased)

in time for Chastisment (1972). The album introduced a sound the group called

“jazzoetry”, leaving behind the spare percussion of the previous

albums in favor of a blending of jazz and funk instrumentation with poetry. The

music further developed into free-jazz–poetry with Hassan’s brief return on

1974’s At Last, as yet the only Last Poets release still unavailable on CD.

The remainder of the 1970s saw a decline in the group’s

popularity. In the 1980s and beyond, however, the group gained renown with the

rise of hip-hop music, often being name-checked as grandfathers and founders of

the new movement, often citing the Jalaluddin solo project Hustler’s Convention

(1973) as their inspiration. Because of this the band was also interviewed in

the 1986 cult documentary Big Fun In The Big Town. Nuriddin and El-Hadi worked

on several projects under the Last Poets name, working with bassist and

producer Bill Laswell, including 1984’s Oh My People and 1988’s Freedom

Express, and recording the final El Hadi–Nuriddin collaboration,

Scatterrap/Home, in 1994.

Sulaiman El-Hadi died in October 1995. Oyewole and Hassan began

recording separately under the same name, releasing Holy Terror in 1995

(re-released on Innerhythmic in 2004) and Time Has Come in 1997.

Their lyrics often dealt with social issues facing

African-American people. In the song “Rain of Terror”, the group

criticized the American government and voiced support for the Black Panthers.

More recently, the Last Poets found fame again refreshed through

a collaboration where the trio (Umar Bin Hassan) was featured with hip-hop

artist Common on the Kanye West-produced song “The Corner,” as well

as (Abiodun Oyewole) with the Wu-Tang Clan-affiliated political hip-hop group

Black Market Militia on the song “The Final Call,” stretching

overseas to the UK on songs “Organic Liquorice (Natural Woman)”,

“Voodoocore”, and “A Name” with Shaka Amazulu the 7th. The

group is also featured on the Nas album Untitled, on the songs “You Can’t

Stop Us Now” and “Project Roach.” Individual members of the

group also collaborated with DST on a remake of “Mean Machine”,

Public Enemy on a remake of “White Man’s God A God Complex” and with

Bristol-based British post-punk band the Pop Group.

In 2010, Abiodun Oyowele was among the artists featured on the

Welfare Poets’ produced Cruel And Unusual Punishment, a CD compilation that was

made in protest of the death penalty, which also featured some several current

positive hip hop artists.

In 2004 Jalal Mansur Nuriddin, a.k.a. Alafia Pudim, a.k.a. Lightning

Rod (The Hustlers Convention 1973), collaborated with the UK-based poet Mark T.

Watson (a.k.a. Malik Al Nasir) writing the foreword to Watson’s debut poetry

collection, Ordinary Guy, published in December 2004 by the Liverpool-based

publisher Fore-Word Press. Jalal’s foreword was written in rhyme, and was

recorded for a collaborative album “Rhythms of the Diaspora (Vol. 1 &

2 – Unreleased) by Malik Al Nasir’s band, Malik & the O.G’s featuring Gil

Scott-Heron, percussionist Larry McDonald, drummers Rod Youngs and Swiss Chris,

New York dub poet Ras Tesfa, and a host of young rappers from New York and

Washington, D.C. Produced by Malik Al Nasir, and Swiss Chris, the albums

Rhythms of the Diaspora; Vol. 1 & 2 are the first of their kind to unite these

pioneers of poetry and hip hop with each other.[8]

In 2011, The Last Poets Abiodun Oyewole and Umar Bin Hassan

performed at The Jazz Cafe in London, in a tribute concert to the late Gil

Scott-Heron and all the former Last Poets.

In 2014, Last Poet Jalaluddin Mansur Nuriddin came to London and

also performed at The Jazz Cafe with Jazz Warriors the first ever live

performance in 40 years of the now iconic “Hustlers Convention”. The

event was produced by Fore-Word Press and featured Liverpool poet Malik Al Nasir

with his band Malik & the O.G’s featuring Cleveland Watkiss, Orphy Robinson

and Tony Remy. The event was filmed as part of a documentary on the

“Hustlers Convention” by Manchester film maker Mike Todd and

Riverhorse Communications. The executive producer was Public Enemy’s Chuck D.

As part of the event Charly Records re-issued a special limited edition of the

vinyl version of Hustlers Convention to celebrate their 40th anniversary. The

event was MC’d by poet Lemn Sissay and the DJ was Shiftless Shuffle’s Perry

Louis.

In 2016, The Last Poets

(World Editions, UK), was published. The novel, written by Christine Otten, was

originally published in Dutch in 2011, and has now been translated by Jonathan

Reeder for English readers. Research more about Black poets and share with your

babies. Make it a champion day!