GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American civil servant and politician. He was chief executive of the District of Columbia from 1967 to 1979, serving as the first and only Mayor-Commissioner from 1967 to 1974 and as the first home-rule mayor of the District of Columbia from 1975 to 1979.After a career in public housing in Washington, DC and New York City, he was appointed as mayor-commissioner of the District of Columbia in 1967.Congress had passed a law granting home rule to the capital, while reserving some authorities. Washington won the first mayoral election in 1974, and served from 1975 until 1979.Today in our History – September 6, 1967 – Walter Edward Washington (April 15, 1915 – October 27, 2003.President Lyndon B. Johnson named Walter E. Washington commissioner and “unofficial” mayor of Washington, D.C.Washington was the great-grandson of enslaved Americans. He was born in Dawson, Georgia. His family moved North in the Great Migration, and Washington was raised in Jamestown, New York, attending public schools. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Howard University and a law degree from Howard University School of Law. He was a member of Omega Psi Phi fraternity.Washington married Bennetta Bullock, an educator. They had one daughter together, Bennetta Jules-Rosette, who became a sociologist. His wife Bennetta Washington became a director of the Women’s Job Corps, and First Lady of the District of Columbia when he was mayor. She died in 1991. After graduating from Howard in 1948, Washington was hired as a supervisor for D.C.’s Alley Dwelling Authority. He worked for the authority until 1961, when he was appointed by President John F. Kennedy as the Executive Director of the National Capital Housing Authority. This was the housing department of the District of Columbia, which was then administered by Congress. In 1966 Washington moved to New York City to head the much larger Housing Authority there in the administration of Mayor John Lindsay. In 1967, President Lyndon Johnson used his reorganization power under Reorganization Plan No. 3 of 1967 to replace the three-commissioner government that had run the capital since 1871 under congressional supervision. Johnson implemented a more modern government headed by a single commissioner, assistant commissioner, and a nine-member city council, all appointed by the president. Johnson appointed Washington Commissioner, which by this time had been informally retitled as “Mayor-Commissioner.” (Power brokers such as Katharine Graham, publisher of the Washington Post, had supported white lawyer Edward Bennett Williams.) Washington was the first African-American mayor of a major American city, and one of three blacks in 1967 chosen to lead major cities. Richard Hatcher of Gary, Indiana and Carl Stokes of Cleveland were elected that year.Washington inherited a city that was torn by racial divisions, and also had to deal with conservative congressional hostility following passage of major civil rights legislation. When he sent his first budget to Congress in late 1967, Democratic Representative John L. McMillan, chair of the House Committee on the District of Columbia, responded by having a truckload of watermelons delivered to Washington’s office.In April 1968, Washington faced riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Although reportedly urged by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover to shoot rioters, Washington refused. He told the Washington Post later, “I walked by myself through the city and urged angry young people to go home. I asked them to help the people who had been burned out.” Only one person refused to listen to him. Republican President Richard Nixon retained Washington after being elected as president in 1968.Congress enacted the District of Columbia Self-Rule and Governmental Reorganization Act on December 24, 1973, providing for an elected mayor and city council. Washington began a vigorous election campaign in early 1974 against six challengers.The Democratic primary race—the real contest in the overwhelmingly Democratic and then-majority black city — eventually became a two-way contest between Washington and Clifford Alexander, future Army Secretary. Washington won the tight race by 4,000 votes. As expected, he won the November general election with a large majority. Home rule took effect when Washington and the newly elected council–the city’s first popularly-elected government since 1871–were sworn into office January 2, 1975. Washington was sworn in by Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall.Although personally beloved by residents, some who nicknamed him “Uncle Walter,” Washington slowly found himself overcome by the problems of managing what was the equivalent of a combination state and city government. The Washington Post opined that he lacked “command presence.” Council chair Sterling Tucker, who wanted to be Mayor, suggested that the problems in the city were because of Washington’s inability to manage city services. Council Member Marion Barry, another rival, accused him of “bumbling and bungling in an inefficiently run city government.”Washington was also constrained by the fact that then as now, the Constitution vested Congress with ultimate authority over the District. Congress thus retained veto power over acts passed by the council, and many matters were subject to council approval.The Washington Monthly noted that Washington’s “gentle ways did not move the city’s bureaucracy. Neither did it satisfy the black voters’ yearning to see the city run by blacks for blacks. Walter Washington was black, but many blacks were suspicious that he was still too tied to the mostly white power structure that had run the city when he was a commissioner.”During his administration he started many new initiatives, for example, the Office of Latino Affairs of the District of Columbia.In the 1978 Democratic mayoral primary, Washington finished third behind Barry and Tucker. He left office on January 2, 1979. Upon his departure from office, he announced that the city had posted a $41 million budget surplus, based on the Federal government’s cash accounting system. When Barry took office, he shifted city finances to the more common accrual system, and he announced that under this system, the city actually had a $284 million deficit. After ending his term as mayor, Washington joined the New York-based law firm of Burns, Jackson, Miller & Summit, becoming a partner. He opened the firm’s Washington, D.C. office.His first wife, Benneta, died in 1991. In 1994, he married Mary Burke Nicholas, an economist and government official. She died November 30, 2014 at age 88. Washington went into semi-retirement in the mid-1990s. He fully retired at the end of the decade in his early eighties. Washington remained a beloved public figure in the District and was much sought after for his political commentary and advice. In 2002, he endorsed Anthony A. Williams for a second mayoral term. Washington’s endorsement carried sufficient weight to be noted by all local news outlets.Washington died at Howard University Hospital on October 27, 2003. Hundreds of mourners came to see him lying in state at the John A. Wilson Building (City Hall), and also attended his funeral at Washington National Cathedral.• 13½ Street, the short alley running alongside the east side of the Wilson Building, was designated Walter E. Washington Way in his honor.• A new housing development in Ward 8 was named the Walter E. Washington Estates.• In 2006, the Council of the District of Columbia named the Washington Convention Center at 801 Mt. Vernon Place NW, as the Walter E. Washington Convention Center. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

Tag: Brandon hardison

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African-American novelist.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African-American novelist. She was the first African American to publish a novel on the North American continent. Her novel Our Nig, or Sketches from the Life of a Free Black was published anonymously in 1859 in Boston, Massachusetts, and was not widely known. The novel was discovered in 1982 by the scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr., who documented it as the first African-American novel published in the United States.Born a free person of color (free Negro) in New Hampshire, she was orphaned when young and bound until the age of 18 as an indentured servant. She struggled to make a living after that, marrying twice; her only son George died at the age of seven in the poor house, where she had placed him while trying to survive as a widow. She wrote one novel. She later was associated with the Spiritualist church, was paid on the public lecture circuit for her lectures about her life, and worked as a housekeeper in a boarding house.Today in our History – September 5, 1859 – Harriet Wilson on, became the first African-American woman to publish a novel. Born Harriet E. “Hattie” Adams in Milford, New Hampshire, she was the mixed-race daughter of Margaret Ann (or Adams) Smith, a washerwoman of Irish ancestry, and Joshua Green, an African-American “hooper of barrels” of mixed African and Indian ancestry.After her father died when Hattie was young, her mother abandoned Hattie at the farm of Nehemiah Hayward Jr., a well-to-do Milford farmer “connected to the Hutchinson Family Singers”.As an orphan, Adams was bound by the courts as an indentured servant to the Hayward family, a customary way for society at the time to arrange support and education for orphans. The intention was that, in exchange for labor, the orphan child would be given room, board and training in life skills, so that she could later make her way in society. From their documentary research, the scholars P. Gabrielle Foreman and Reginald H. Pitts believe that the Hayward family were the basis of the “Bellmont” family depicted in Our Nig. (This was the family who held the young “Frado” in indentured servitude, abusing her physically and mentally from the age of six to 18. Foreman and Pitts’ material was incorporated in supporting sections of the 2004 edition of Our Nig.)After the end of her indenture at the age of 18, Hattie Adams (as she was then known), worked as a house servant and a seamstress in households in southern New Hampshire. Adams married Thomas Wilson in Milford on October 6, 1851. An escaped slave, Wilson had been traveling around New England giving lectures based on his life. Although he continued to lecture periodically in churches and town squares, he told Hattie that he had never been a slave and that he had created the story to gain support from abolitionists.Wilson abandoned Harriet soon after they married. Pregnant and ill, Harriet Wilson was sent to the Hillsborough County, New Hampshire Poor Farm in Goffstown, where her only son, George Mason Wilson, was born. His probable birth date was June 15, 1852. Soon after George’s birth, Wilson reappeared and took the two away from the Poor Farm. He returned to sea, where he served as a sailor, and died soon after.As a widow, Harriet Wilson returned her son George to the care of the Poor Farm, as she could not make enough money to support them both and provide for his care while she worked. However, George died at the age of seven on February 16, 1860 of bilious fever. After that, Wilson moved to Boston, hoping for more work opportunities. On September 29, 1870, Wilson married again, to John Gallatin Robinson in Boston. An apothecary, he was either a native of Canada born in Sherbrooke, Quebec or of Woodbury, Connecticut. Robinson was of English and German ancestry; he was nearly 18 years younger than Wilson.From 1870-1877, they resided at 46 Carver Street, after which they appear to have separated. After that date, city directories list Wilson and Robinson in separate lodgings in Boston’s South End. No record has been found of a divorce, but divorces were infrequent at the time.While living in Boston, Wilson wrote Our Nig. On August 14, 1859, she copyrighted it, and deposited a copy of the novel in the Office of the Clerk of the U.S. District Court of Massachusetts.On September 5, 1859, the novel was published anonymously by George C. Rand and Avery, a publishing firm in Boston. Wilson says in the book’s preface she wrote the novel to raise money to help care for her sick child, George. In 1863, Harriet Wilson appeared on the “Report of the Overseers of the Poor” for the town of Milford, New Hampshire. After 1863, she disappeared from records until 1867, when she was listed in the Boston Spiritualist newspaper, Banner of Light, as living in East Cambridge, Massachusetts. She subsequently moved across the Charles River to the city of Boston, where she became known in Spiritualist circles as “the colored medium.” From 1867 to 1897, “Mrs. Hattie E. Wilson” was listed in the Banner of Light as a trance reader and lecturer. She was active in the local Spiritualist community, and she would give “lectures,” either while entranced, or speaking normally, wherever she was wanted. She spoke at camp meetings, in theaters and meeting houses and in private homes throughout New England; she shared the podium with speakers such as Victoria Woodhull, Cora L. V. Scott and Andrew Jackson Davis. In 1870 Wilson traveled as far as Chicago, Illinois as a delegate to the American Association of Spiritualists convention. Wilson delivered lectures on labor reform, and children’s education. Although the texts of her talks have not survived, newspaper reports imply that she often spoke about her life experiences, providing sometimes trenchant and often humorous commentary.Wilson worked as a Spiritualist nurse and healer (“clairvoyant physician”); as a “spiritual healer,”she was also available for medical consultations and would make house calls. She was active in the organization and operation of Children’s Progressive Lyceums, that served as Sunday Schools for the children of Spiritualists; she organized Christmas celebrations; she participated in skits and playlets; and at meetings she sometime sang as part of a quartet.She was also known for her floral centerpieces, and the candies she would make for the children were long remembered. In addition, for nearly 20 years from 1879 to 1897, she was the housekeeper of a boardinghouse in a two-story dwelling at 15 Village Street (near the present corner of East Berkeley Street and Tremont Streets in the South End.) She rented out rooms, collected rents and provided basic maintenance.In Wilson’s active and fruitful life after Our Nig, there is no evidence that she wrote anything else for publication.On June 28, 1900, Hattie E. Wilson died in the Quincy Hospital in Quincy, Massachusetts. She was buried in the Cobb family plot in that town’s Mount Wollaston Cemetery. Her plot number is listed as 1337, “old section.” The scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr. rediscovered Our Nig in 1982 and documented it as the first novel by an African American to be published in the United States. His discovery and the novel gained national attention, and it was reissued with an introduction by Gates. It has subsequently been republished in several other editions. In 2006, William L. Andrews, an English literature professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Mitch Kachun, a history professor at Western Michigan University, brought to light Julia C. Collins’ The Curse of Caste; or The Slave Bride (1865), first published in serial form in The Christian Recorder, newspaper of the AME Church. Publishing it in book form in 2006, they maintained that The Curse of Caste should be considered the first “truly imagined” novel by an African American to be published in the U.S. They argued that Our Nig was more autobiography than fiction.Gates responded that numerous other novels and other works of fiction of the period were in some part based on real-life events and were in that sense autobiographical, but they were still considered novels. Examples include Fanny Fern’s Ruth Hall (1854), Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1868–69), and Hannah Webster Foster’s The Coquette (1797). The first known novel by an African American is William Wells Brown’s Clotel; or, The President’s Daughter (1853), published in the United Kingdom, where he was living at the time. The critic Sven Birkerts argued that the unfinished state of The Curse of Caste (Collins died before completing it) and its poor literary quality should disqualify it as the first building block of African-American literature. He contended the works by Wilson and Brown were more fully realized. Eric Gardner thought that Our Nig did not receive critical acclaim from abolitionists when first published because it did not conform to the contemporary genre of slave narratives. He thinks the abolitionists may have refrained from promoting Our Nig because the novel recounts “slavery’s shadow” in the North, where free blacks suffered as indentured servants and from racism. It fails to offer the promise of freedom, and it features a protagonist who is assertive toward a white woman. In her article “Dwelling in the House of Oppression: The Spatial, Racial, and Textual Dynamics of Harriet Wilson’s Our Nig,” Lois Leveen argues that, although the novel is about a free black in the north, the “free black” is still oppressed. The “white house” of the novel represents, as Leveen puts it:”The model home for American society is built according to the spatial imperatives of slavery.” Frado is a “free black”, but she is treated as a lower-class person and is often abused as a slave would be. Leveen argues that Wilson was expressing her view that even the “free blacks” were not really free in a racist society. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event took place at Cortlandt Manor, Westchester County, New York, in 1949.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event took place at Cortlandt Manor, Westchester County, New York, in 1949. The catalyst for the rioting was an announced concert by black singer Paul Robeson, who was well known for his strong pro-trade union stance, civil rights activism, communist affiliations, and anti-colonialism. The concert, organized as a benefit for the Civil Rights Congress, was scheduled to take place on August 27 in Lakeland Acres, just north of Peekskill. Today in our History – September 4, 1949 – Paul Robeson event causes a riot.On the afternoon of Sunday, September 4, 1949, violence broke out after renowned but controversial African American baritone Paul Robeson sang at an outdoor concert near Peekskill, New York, to a mixed-race audience of more than 20,000 people. This was a rescheduled performance. The original concert, slated for August 27 as a benefit for the leftist Civil Rights Congress, had been preempted by violence aimed at Robeson’s race and politics. While the second concert itself went off peacefully despite nearby protests, concertgoers leaving the venue were ambushed by attackers who threw stones and overturned cars while local police stood by. Together, the two incidents have come to be known as the Peekskill Riots, and interpreted not only as a test case for free speech rights, but as a harbinger of both the reactionary politics and protest movements that would unfold in the post-WWII era.Paul Robeson had performed in the Peekskill area for several years without incident, but several factors converged to generate new controversy in 1949. The singer-actor’s left politics were well-known, as was his advocacy for civil rights. Considered a Communist “fellow traveler,” he had first visited the Soviet Union in 1934, where he claimed that he was treated with a level of respect he had never experienced in his own country. By 1947, as the Cold War heated up, the House Un-American Activities Committee had started its investigations into alleged Communist influence in Hollywood, and Robeson was one of the targeted performers. Robeson had, in fact, put his career on hold to help organize the Progressive Party’s 1948 presidential campaign. But then, in April, 1949, he gave a speech at the Congress of the World Partisans of Peace in Paris that was widely covered, and likely misquoted, in the American press—recasting his intended pacifist and antiracist message as a strongly pro-Communist one. One article from Peekskill’s local Evening Star newspaper, for example, featured the subhead “Robeson Says U.S. Negro Won’t Fight Russia.” In addition, the newly-controversial Robeson’s pending appearance helped to catalyze the simmering resentments of year-round Peekskill residents toward the area’s Jewish summer community. A mix of union members and professionals, some immigrants, some political radicals, Jewish New Yorkers routinely escaped the heat of the city at upstate camps and bungalow colonies; near Peekskill, their presence more than doubled the size of the area’s population each year. When local chapters of the American Legion and other veterans’ groups, as well as the Chamber of Commerce, set themselves in public opposition to Robeson’s concert in the name of patriotism, there was an undercurrent of deeper tensions in the rhetoric. “The time for tolerant silence that signifies approval is running out,” proclaimed one Evening Star editorial on August 22. Once protest against Robeson’s appearance did turn violent, the violence was directed especially at the members of his audience, who were taunted with racist and anti-Semitic epithets or openly assaulted. “The outbreak thus embodies the combined expressions of the most explosive prejudices in American life—against Communists, Negroes and Jews,” claimed one report soon after. As a singer Robeson was known for his renditions of spirituals and folk songs as well as show tunes he had helped to popularize such as Showboat’s “Ol’ Man River.” His first Peekskill concert had been planned by People’s Artists Inc., a group recently started by rising folk singer Pete Seeger to facilitate bookings. Novelist Howard Fast was the intended emcee who, because he had arrived before the rioting started, became a defacto leader for the hundreds of audience members trapped on the concert grounds. Fast’s book-length Peekskill, USA: A Personal Experience recounts events such as the burning of a cross on a nearby hill, blockades at nearby roadways, attack on the makeshift stage and destruction of thousands of rented wooden chairs on the evening of August 27. Robeson had not made it past the blockades to the concert grounds that day. Once he returned to Harlem, at a press conference denouncing the violence he vowed to come to Peekskill again and sing. Plans quickly emerged for a larger concert at a different venue the following weekend. This time, both Robeson and his audience were protected by a body guard of WWII veterans and union members on the stage, with a ring of hundreds more surrounding the venue. The show of solidarity led Pete Seeger—who both sang at the concert and whose car was later attacked with stones—to write “Hold the Line” with his colleague Lee Hayes, which was recorded by their folk group The Weavers soon after:Let me tell you the story of a line that was held,And many men and women whose courage we know well,As they held the line at Peekskill on that long September day,We will hold the line forever till the people have their way.Within a few days, hundreds of editorials and letters appeared in newspapers across the nation and abroad, by prominent individuals, organizations, trade unions, churches and others. They condemned not only the attacks but also the failure of Governor Dewey and the State Police to protect the lives and property of citizens, and called for a full investigation of the violence and prosecution of the perpetrators. Despite condemnation from progressives and civil rights activists, the mainstream press and local officials overwhelmingly blamed Robeson and his fans for “provoking” the violence. Following the Peekskill riots, other cities became fearful of similar incidents, and over 80 scheduled concert dates of Robeson’s were canceled. On September 12, 1949, in response to Robeson’s controversial status in the press and leftist affiliations, the National Maritime Union convention considered a motion that Robeson’s name be removed from the union’s honorary membership list. The motion was withdrawn for lack of support among members. Later that month, the All-China Art and Literature Workers’ Association and All-China Association of Musicians of Liberated China protested the Peekskill attack on Robeson. On October 2, 1949, Robeson spoke at a luncheon for the National Labor Conference for Peace, Ashland Auditorium, Chicago, and referenced the riots.In recent years, Westchester County has gone to great lengths to make amends to the survivors of the riots by holding a commemorative ceremony, at which an apology was made for their treatment.In September 1999, county officials held a “Remembrance and Reconciliation Ceremony, 50th anniversary commemoration of the 1949 Peekskill riots.” It included speakers Paul Robeson, Jr., folk singer Peter Seeger and several local elected officials. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champions were called “The Two Real Coons”! The duo called themselves the “Two Real Coons” as most of the talent in vaudeville were primarily white and were painted in blackface.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champions were called “The Two Real Coons”! The duo called themselves the “Two Real Coons” as most of the talent in vaudeville were primarily white and were painted in blackface. At first the lighter-skinned Bert Williams would trick the darker Walker in their skits, but after a while the two noticed the crowd reacted better when the two reversed roles. Williams dawned the burnt cork black face while George Walker, the “dandy” performed without any makeup at all.Blackface was said to work as a double mask for Williams as it emphasized that he was different from vaudevillians and white audiences. Williams played the role of the comic figure in blackface while George Walker played the straight man, an obvious counter to the dominant negative stereotypes of the time.While performing their vaudeville act throughout the United States, the “Two Real Coons” headlined at the Koster and Bial’s vaudeville house where they popularized the cakewalk, a dance competition in which the winning couple was rewarded with a cake.Today in our History – September 3, 1898 – The twosome debuted in New York at the Casino Theatre in 1898. Their act, “The Gold Bug” consisted of songs, dance that focused on Walker trying to convince Williams to join him in get-rich-quick schemes.George Walker and Bert Williams were two of the most renowned figures of the minstrel era. However the two did not start their careers together. Walker was born in 1873 in Lawrence, Kansas. His onstage career began at an early age as he toured in black minstrel shows as a child. George Walker became a better known stage performer as he toured the country with a traveling group of minstrels. George Walker was a “dandy”, a performer notorious for performing without makeup due to his dark skin. Most vaudeville actors were white at this time and often wore blackface. As Walker and his group traveled the country, Bert Williams was touring with his group, named Martin and Selig’s Mastodon Minstrels. While performing with the Minstrels, African American song-and-dance man George Walker and Bert Williams met in San Francisco in 1893. George Walker married Ada Overton in 1899. Ada Overton Walker was known as one of the first professional African American choreographers. Prior to starring in performances with Walker and Williams, Overton wowed audiences across the country for her 1900 musical performance in the show Son of Ham. After falling ill during the tour of Bandana Land in 1909, George Walker returned to Lawrence, Kansas where he died on January 8, 1911. He was 38. Bert Williams was born on November 12, 1874 in Nassau, Bahamas and later moved to Riverside, California. Williams began his performance career in 1886 when he joined Lew Johnson’s Minstrels. In 1893,while he was still a teenager, Williams joined Martin and Selig’s Mastodon Minstrels. Bert Williams had very fair skin for an African-American man which allowed him easier access to the white dominated vaudeville scene. George Walker and Bert Williams performed many song and dance numbers, comedic skits as well as comedic songs. The twosome debuted in New York at the Casino Theatre in 1898. Their act, “The Gold Bug” consisted of songs, dance that focused on Walker trying to convince Williams to join him in get-rich-quick schemes. Later in life Williams went on to a solo career and then worked for a company called the Ziegfeld Follies. On February 21, 1922 Williams collapsed on stage while performing and later returned to New York City. He died a month later on March 4, 1922.Offstage life was different for the two men. Both men faced extreme racism. Racial prejudice was said to have shaped Bert William’s career as he based his humor on universal situations in which it was possible that one of the audience member would find themselves. Often, white vaudevillians would refuse to appear on the same playbill as Williams, and it is said that others complained that his material was better than theirs. As a comedian and songwriter he was loved by all, however he often faced racism even by the restaurants and hotels that he played for. Williams was forced to perform in blackface makeup, gloves and other attire as he consistently played out stereotypical black characters. After Williams’ death on March 4, 1922 the Chicago Defender stated that “No other performer in the history of the American stage enjoyed the popularity and esteem of all races and classes of theater-goers to the remarkable extent gained by Bert Williams.”George Walker fought against racism as he provided a place within the company for colored artists which enabled an African American presence on stages across the country. George Walker was an esteemed businessman who was in charge of managing the affairs of the Walker and Williams Company. A company that brought them and those that worked for them fame and wealth both nationally and internationally.In 1903, they performed “In Dahomey” an elaborate play at Buckingham Palace in London. This was “the first full length musical written and played by blacks to be performed at a major Broadway house”. The play contained original music, props, and scenery. George Walker played a hustler disguised as a prince from Dahomey who was sent by a group of deceitful investors to convince blacks to join a colony. Other Williams and Walker Company productions include: The Sons of Ham (1900), The Policy Players (1899), and Bandana Land (1908).Williams and Walker, together with eight other members of their vaudeville troupe were Initiated into Scottish Freemasonry on 2 May, Passed on 16 May and Raised on 1 June 1904. Research more about this great American Champion event and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was born to sharecropper Wilder Berry and his wife, Lucy Wright Berry, near Glendora in Leflore County, Mississippi, on 2 September 1924.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was born to sharecropper Wilder Berry and his wife, Lucy Wright Berry, near Glendora in Leflore County, Mississippi, on 2 September 1924. After her father left the family, Lucy Berry raised her and her brother, W. C., in Tutwiler, in Tallahatchie County. When she was just fourteen, she married Paul Pigee Jr., who was four years older, and their daughter, Mary Jane, was born the day before her sixteenth birthday. After studying cosmetology in Chicago, she opened a Beauty Salon in Clarksdale.Today in our History – September 2, 1924 – Vera Mae Berry was born. Vera Mae Berry was Pigee worked with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and was the only woman among the early local movement leaders. She helped to charter the group’s Coahoma County branch in 1953 before leaving the area to study cosmetology in Chicago.She returned to Clarksdale in 1955 and resumed her activism. She served as secretary of the Coahoma branch of the NAACP for about twenty years. When the NAACP’s Coahoma County Youth Council was chartered in 1959, she served as the group’s adviser, while her daughter served as president. In December 1961 the two women and a family friend staged a protest that resulted in the desegregation of Clarksdale’s bus terminal. Pigee became a surrogate mother to many young activists, feeding them and providing them shelter in her home and salon. She also helped to organize the area’s citizenship schools and taught classes to prepare African Americans to register to vote. Because she was self-employed, she had relative economic immunity against retaliation for her organizing efforts in the Delta, although her home suffered a bombing and she was arrested regularly. Pigee exhibited extraordinary bravery, which she credited to the example provided by her mother, who, driven by religious faith, refused to allow segregation to dictate how she was treated. Pigee helped to establish the Council of Federated Organizations but became one of its first critics, clashing with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee workers who continuously berated NAACP officials.Pigee left Clarksdale in the early 1970s to study sociology and journalism, earning a doctorate from Wayne State University in Detroit. After movement history in Mississippi rendered Pigee and her loyalty to the NAACP invisible, she wrote and published a two-part autobiography, Struggle of Struggles, during the 1970s. She continued her activism with the NAACP in Michigan and became an ordained Baptist minister, residing in Detroit until her death on 18 September 2007.Vera Mae Pigee was an active member of the Coahoma Chapter of the NAACP. She helped Aaron Henry found the chapter and directed the Youth Council. Under her leadership, black members of the Youth Council entered the whites-only train station, attempted to purchase tickets, and were arrested. Pigee herself, along with other women in Clarksdale, desegregated the whites-only bus terminal by sitting in the waiting room day after day and appealing to the U.S. Department of Justice. After being threatened with a lawsuit, the bus terminal removed its “Whites Only” signs.Mississippi had pockets of strong local civil rights activity before the Freedom Riders entered the state, but their presence in 1961 propelled the local movement to new heights.Most of the local civil rights movements began in the 1950s, in churches, homes, and in the back rooms of small black-owned businesses across the state. Their activities were quietly organized, and struggles against discrimination were small and localized, because it was too dangerous to make large public statements and draw too much attention to the activists. The whites in power who wanted to maintain and strengthen segregation had little tolerance for black resistance, and they worked hard to navigate ways out of implementing the 1954 U. S. Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education decision that ruled segregated public schools unconstitutional. But their efforts did not kill the local civil rights movements.Before the young people in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee or the Congress of Racial Equality entered Mississippi on the Freedom Ride buses in 1961, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People had branches throughout Mississippi. Most of the state’s NAACP branches were formed after World War II had ended in 1945. Moreover, in the early 1950s the national office in New York City sought to increase its membership and build on the momentum from its Supreme Court successes in dismantling Jim Crow, or the system of denying African Americans civil liberties and enforcing segregation. Some Mississippi branches were more organized and viable than others, depending on the areas where active and strong all-white Citizens’ Councils or more violent vigilante groups had also organized.One of the most active NAACP branches was in Clarksdale, Mississippi, covering the whole of Coahoma County. In 1951 a group of local black people, under the leadership of World War II veteran and pharmacist Aaron Henry, formed a Clarksdale/Coahoma County NAACP branch to harness the resources of the larger national organization. The group received its charter in 1953 and remained at the fore of civil rights activities in the Mississippi Delta for years. In fact, the branch had such a large active membership that SNCC and CORE had little to do there and focused more on other towns and counties in the state.Vera Mae Pigee, who owned a beauty shop in the heart of the black neighborhood in downtown Clarksdale, had helped Henry organize the Clarksdale/Coahoma County NAACP chapter. She then worked principally with local black youth under the auspices of the NAACP Youth Council program. Pigee also served as Clarksdale/Coahoma NAACP branch secretary and as the state’s Youth Council advisor.The Youth Council undertook many activities that helped the adult officers and leaders of the local branch meet their goals. For instance, in the spring of 1961 many young people went door-to-door in Clarksdale during the NAACP’s Crusade for Voters. They also announced the program in their churches and schools. The result of the Youth Council efforts produced one hundred new voters.The 1961 Freedom Riders did not pass through Clarksdale, yet the town’s civil rights activities in 1961 were strong, producing local drama and stories. For example, on August 23, a Wednesday afternoon after lunch, three black youths walked into the white waiting room of the Illinois Central Railroad Station in Clarksdale. They approached the ticket agent and asked for tickets for the next Memphis-bound train. The agent refused them service and a bystander called the police and the local newspaper. The young people were Mary Jane Pigee, aged eighteen, a college student at Central State College in Wilberforce, Ohio, and a former local Youth Council president; Adrian Beard, aged sixteen and a student at Immaculate Conception Catholic School; and fourteen-year-old Wilma Jones, a student at Higgins High School. When Police Chief Ben C. Collins arrived with another officer, the protesters refused to move to the “colored side” of the station and remained quietly seated. The officers took them into custody and charged them with intent to breach the peace.The Youth Council, under the leadership of Vera Pigee, the mother of Mary Jane, had sponsored the demonstration, and it resulted in their first formal direct-action arrest. The Youth Council wanted to test the breach of peace statute that so many young people had “violated” in the last twenty months since the beginning of the mass sit-ins across the nation and the Freedom Rides in action elsewhere.The local jury convicted the three young people on the basis they had violated a Mississippi statute that segregated waiting rooms.Pigee encouraged her daughter’s desire to participate in protests and sit-ins despite the obvious risks. To be a mother — to her daughter and to the Civil Rights Movement — was for Pigee a duty and a great responsibility. Her confidence convinced others that she did not ask of them what she was not willing to do herself.She could assure parents of their children’s safety while in her care and gained their trust through her own struggles. She did not let the youth take the burden of direct action alone.In fact, in the fall of 1961, weeks after her daughter’s own protest at the railway station, Pigee and Idessa Johnson, another member of the NAACP Clarksdale branch, walked into the whites-only section of the Clarksdale Greyhound Bus Terminal. It was a personal goal for Pigee to desegregate the bus terminal. Pigee knew that her daughter would not use the designated black side of the terminal when she traveled home from college at Christmas. Pigee decided to protest on Mary Jane’s behalf. On entering the terminal, the women did not find resistance, and Pigee asked for a round-trip ticket from Cincinnati, Ohio, to Clarksdale and for an express bus schedule. The transaction took place without incident. Pigee and Johnson walked away slowly, pausing to marvel at the spacious, air-conditioned white section, drinking at the water fountain, and visiting the ladies room before leaving.Mary Jane Pigee came home for Christmas entering on the white side of the bus terminal. But when it was time for her to return to school, four policemen entered the white waiting room where she sat with her mother and a family friend. Harassing them with a barrage of questions, the officers threatened arrest. The women filed complaints with the NAACP, U. S. Department of Justice, Interstate Commerce Commission, local F.B.I., and police. Protesters repeated the ritual until on December 27, 1961, the Clarksdale Press Register reported that all the segregation signs had disappeared from the Clarksdale bus terminal and the Clarksdale train station. Police had voluntarily removed the signs after the Justice Department informed the city that it faced a law suit.Pigee’s desegregation of the bus terminal symbolized the beginning of a more aggressive style of protest in Clarksdale, one already practiced in other counties and southern states. Their actions in Clarksdale took shape against the backdrop of rising student-led protest across the South, a mass of movements that increasingly pushed well past the adult leadership of old-line civil rights organizations, such as their beloved NAACP.On Thanksgiving Day in 1961, for instance, Clarksdale’s mayor banned the two bands from black Higgins High School and Coahoma County Junior College from the annual Christmas Parade, a tradition for the black schools since the late 1940s.Rather than discouraging civil rights activities, the mayor’s move added fuel to the protest fires. Working with the children in the Youth Council, Pigee had immediate contact with the black parents. Punishing the youth during the season of good will provoked angry parents to act when they might not have before.Indeed, it was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. The Youth Council debated its response at Pigee’s beauty shop in a mass meeting, which Pigee had called the night following the ban announcement. Pigee said, “These are our children,” and it was that sentiment that sustained a two-year boycott of downtown businesses under the phrase, “No Parade, No Trade.” Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

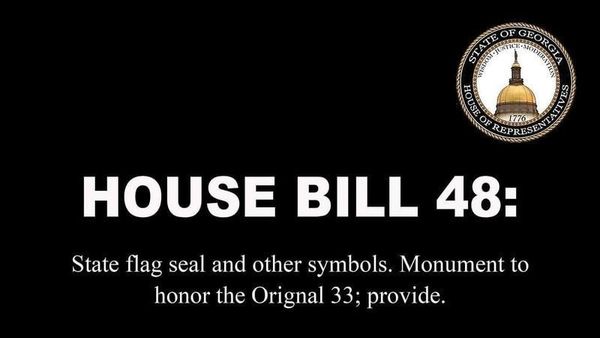

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event was were the first 33 African-American members of the Georgia General Assembly who were elected to office in 1868, during the Reconstruction era.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event was were the first 33 African-American members of the Georgia General Assembly who were elected to office in 1868, during the Reconstruction era. They were among the first African-American state legislators in the United States. Twenty-four of the members were ministers.After most of the legislators voted for losing candidates in the legislature’s elections for the U.S. Senate, the white majority conspired to remove the black and mixed-ethnicity members from the Assembly. Most of the black delegates to the state’s post-war constitutional convention voted against including into the constitution the right of black legislators to hold office, a vote which Rep. Henry McNeal Turner came to regret.The members were expelled by September 1868. The ex-legislators petitioned the federal government and state courts to intervene. In White v. Clements (June 1869), the Supreme Court of Georgia ruled 2-1 that black people did have a right to hold office in Georgia. In January 1870, commanding general of the District of Georgia Alfred H. Terry began “Terry’s Purge”, removing ex-Confederates from the General Assembly, replacing them with Republican runners-up and reinstating the black legislators, resulting in a Republican majority in both houses. From that point, the General Assembly accomplished the ratification of the 15th Amendment, chose new senators to go to Washington, and adopted public education.The work of the Republican majority was short-lived, after the “Redeemer” Democrats won majorities in both houses in December 1870. The Republican governor, Rufus Bullock, after trying and failing to reinstate federal military rule in Georgia, fled the state. After the Democrats took office they began to enact harsh recriminations against Republicans and African Americans, using terror, intimidation, and the Ku Klux Klan, leading to disenfranchisement by the 1890s. One quarter of the black legislators were killed, threatened, beaten, or jailed. The last African-American legislator, W. H. Rogers, resigned in 1907. Afterwards, no African American held a seat in the Georgia legislature until civil rights attorney Leroy Johnson, a Democrat, was elected to the state senate in 1962.The 33 are commemorated in the sculpture Expelled Because of Color on the grounds of the Georgia State Capitol.Today in our History – September 1, 1868 – The “Original 33” were seated in the General Assembly of Georgia.At that time, each State Senator in Georgia represented a single-member district made up of three contiguous counties, numbered from 1 to 44. Population was not considered when drawing State Senate districts. Each State Representative in Georgia represented a county, with counties having between one and three representatives depending on population.In 1976, the Original 33 were honored by the Black Caucus of the Georgia General Assembly with a statue that depicts the rise of African-American politicians. It is on the grounds of the Georgia State Capitol in Atlanta.The “Expelled Because of Their Color” monument is located near the Capitol Avenue entrance of the Georgia State Capitol. It was dedicated to the 33 original African-American Georgia legislators who were elected during the Reconstruction period. In the first election (1868) after the Civil war, blacks were allowed to vote. But even though former slaves could now vote, there was no law that allowed black representatives to hold office. So, the 33 black men who were elected to the General Assembly were expelled. The construction of this monument was funded by the Black Caucus of the Georgia General Assembly, a group of African-American State representatives and senators who are committed to the principles and ideals of the Civil Rights Movement organized in 1975. The Georgia Legislative Black Caucus commissioned the sculpture in March 1976 (Boutwell). John Riddle, the Sculptor of this monument, was also a painter and printmaker known for artwork that acknowledged the struggles of African-Americans through history.— Carlisa SimonInscribed on the base of Riddle’s sculpture are the names of the 33 black pioneer legislators of the Georgia General Assembly elected and expelled in 1868 and reinstated in 1870 by an Act of Congress.The Georgia Legislative Black Caucus continues to hold annual events honoring the Original 33. Research more about this great American Champion event and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American jazz vibraphonist, pianist, percussionist, and bandleader.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American jazz vibraphonist, pianist, percussionist, and bandleader. He worked with jazz musicians from Teddy Wilson, Benny Goodman, and Buddy Rich, to Charlie Parker, Charles Mingus, and Quincy Jones. In 1992, he was inducted into the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame, and he was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1996.Today in our History – August 31 – Lionel Leo Hampton (April 20, 1908 – August 31, 2002) dies.Lionel Hampton is one of the most extraordinary musicians of the 20th century and his artistic achievements symbolize the impact that jazz music has had on our culture in the 21st century.He was born April 20, 1908 in Louisville, Kentucky. His father, Charles Hampton, a promising pianist and singer, was reported missing and later declared killed in World War I. Lionel and his mother, Gertrude, first moved to Birmingham, Alabama, to be with her family, then settled in Chicago.He attended the Holy Rosary Academy, near Kenosha, Wisconsin, where a Dominican sister give him his first drum lessons.Later, while attending St. Monica’s School in Chicago, Lionel got a job selling papers in order to join the Chicago Defender’s Newsboys Band. At first, he helped carry the bass drum, and later played the snare drum.While in high school, Les Hite gave Lionel a job in a teenage band. Later, the 15-year-old Lionel, who had just graduated from high school, promised his grandmother he would continue to say his daily prayers and left for Los Angeles to join Reb Spikes’s Sharps and Flats. He also played with Paul Howard’s Quality Serenaders and a new band organized by Hite, which backed Louis Armstrong at the Cotton Club.In 1930, Hampton was called in to a recording session with Armstrong, and during a break Hampton walked over to a vibraphone and started to play. He ended up playing the vibes on one song. The song became a hit; Hampton had introduced a new voice to jazz and he became “King of the Vibes.”When Benny Goodman heard him play, Goodman immediately asked Hampton to record with him, Gene Krupa on drums and Teddy Wilson on piano. The Benny Goodman Quartet recorded the jazz classics “Dinah,” “Moonglow,” “My Last Affair,” and “Exactly Like You.” Hampton’s addition to the groups also marked the breaking of the color barrier; the Benny Goodman Quartet was the first racially integrated group of jazz musicians.Hampton and his wife, Gladys, were married Nov. 11, 1936. Gladys served as his personal manager, and developed a reputation as a brilliant businesswoman. She was responsible for raising the money for Lionel to start his own band.As a bandleader, he established the Lionel Hampton Orchestra that became known around the world for its tremendous energy and dazzling showmanship. “Sunny Side of the Street,” “Central Avenue Breakdown” (his signature tune), “Flying Home,” and “Hamp’s Boogie-Woogie” all became top-of-the-chart best-sellers upon release. The name Lionel Hampton became world famous overnight, and the Lionel Hampton Orchestra had a phenomenal array of sidemen.The band also initiated the first phase of Hampton’s career as an educator by graduating such talents as Illinois Jacquet, Cat Anderson, Dexter Gordon, Art Farmer, Clifford Brown, Fats Navarro, Clark Terry, Quincy Jones, Charles Mingus, Wes Montgomery, and singers Joe Williams, Dinah Washington, Betty Carter and Aretha Franklin. The Lionel Hampton Orchestra became known around the world for its first-class jazz musicianship.As a composer and arranger, Hampton wrote more than 200 works, including the jazz standards Flying Home, Evil Gal Blues, and Midnight Sun. He also composed the major symphonic work, “King David Suite.”As a statesman, he was asked by President Eisenhower to serve as a goodwill ambassador for the United States, and his band made many tours to Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and the Far East, generating a huge international following. President George Bush appointed him to the Board of the Kennedy Center, and President Clinton awarded him the National Medal of the Arts.As a businessman, he established two record labels, his own publishing company, and he founded the Lionel Hampton Development Corporation to build low-income housing in inner cities.In his continuing role as an educator, he began working with the University of Idaho in the early 1980s to establish his dream for the future of music education. In 1985, the University named its jazz festival for him, and in 1987 the University’s music school was named the Lionel Hampton School of Music. The Lionel Hampton International Jazz Festival, The Lionel Hampton School of Music, and the International Jazz Collections archives of the UI Library are all designed to help teach and preserve the heritage of jazz.Lionel Hampton passed away Saturday, August 31, 2002. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American jazz saxophonist.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American jazz saxophonist.Today in our History – August 30, 1957 – Gerald Albright (born August 30, 1957) is born. Born in Los Angeles, Albright grew up in its South Central neighborhood. He began piano lessons at an early age, although he professed no interest in the instrument. His love of music picked up when he was given a saxophone that belonged to his piano teacher. It further reinforced when he attended Locke High School. After high school, he attended the University of Redlands where he was initiated into the Iota Chi Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha and received a degree in business management with a minor concentration on music. He switched to bass guitar after he saw Louis Johnson in concert.After college, Albright worked as a studio musician in the 1980s for Anita Baker, Ray Parker Jr., Olivia Newton-John, and The Temptations. He joined Patrice Rushen, who was forming a band, in which he played saxophone.When the bassist left in the middle of a tour, Albright replaced him and finished the tour playing bass guitar. Around the same time, he began to tour Europe with drummer Alphonse Mouzon. He has also toured with Anita Baker, Phil Collins, Johnny Hallyday, Whitney Houston, Quincy Jones, Jeff Lorber, and Teena Marie. In addition to appearances at clubs and jazz festivals, he has been part of Jazz Explosion tours on which he played with Will Downing, Jonathan Butler, Chaka Khan, Hugh Masekela, and Rachelle Ferrell.Albright has appeared in the television programs A Different World, Melrose Place and jazz segments for Black Entertainment Television, as well as piloting a show in Las Vegas with Meshach Taylor of Designing Women. He was one of ten saxophonists to perform at the inauguration of President Bill Clinton.His saxophone work appears in the PlayStation video game Castlevania: Symphony of the Night during the theme song “I Am the Wind”, which includes keyboardist Jeff Lorber. He launched his solo career in the infancy of what became the smooth jazz format, with Just Between Us in 1987 and has been a core part of the genre with chart-topping albums, countless radio hits and as a member of many all star tours, including Guitars & Saxes and Groovin’ For Grover. In the late 90s, he fronted a big band for and toured with pop star Phil Collins and did a dual recording with vocal great Will Downing called Pleasures of the Night. Between his last two Grammy-nominated solo albums Pushing The Envelope (2010) and Slam Dunk (2014), he enjoyed hit collaborations with two huge hits – 24/7 with guitarist Norman Brown and Summer Horns by Dave Koz and Friends (including Mindi Abair and Richard Elliot), which were also Grammy-nominated for Best Pop Instrumental Albums. He toured with Brown and Summer Horns, and most recently has been on the road with South Africa gospel/jazz singer and guitarist Jonathan Butler. Albright’s other albums whose titles perfectly reflect their flow include Smooth (1994), Groovology (2002), Kickin’ It Up (2004) and Sax for Stax (2008).Because Albright’s musical muse has taken him to so many fascinating locales along the contemporary R&B/urban jazz spectrum, he’s joyfully defied easy categorizations.“Top to bottom,” Albright says, “Whether in concert, listening to my music over the radio or CD player, I always want my listeners to be taken on a musical journey with different textures, rhythms, chord progressions and moods. I want people to know where I’ve been and where I’m going, and to let them hear that I’m in a really good place in my life.” Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event was centered in the “City of Brotherly Love” as Heavily armed Philadelphia police contingents swooped down on three Black Panther party centers at dawn on this day.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event was centered in the “City of Brotherly Love” as Heavily armed Philadelphia police contingents swooped down on three Black Panther party centers at dawn on this day.Gunfire was exchanged in two of the raids before tear gas forced the occupants into the street.Fifteen youthful blacks, 10 men and 5 women, were taken into custody. Later that night one was released, and the 14 others were arraigned on charges of assault with intent to kill and other weapons charges. Judge Leo Weinrott ordered each of the 14 held on $100,000 bail.Three policemen were wounded, two superficially, by shot gun pellets fired from the Panther Information Center at 1935 Columbia Avenue in the black section of the near North Side.The shootings increased police casualties in the city that night to one dead and six wounded in confrontations with blacks.Today in our History – August 29, 1970 – Heavily armed Philadelphia police contingents swooped down on three Black Panther party centers.Police Commissioner Frank L. Rizzo announced at a news conference late that afternoon that 13 guns and 1,000 rounds of ammunition were confiscated in the raids. No Panther injuries were reported.The commissioner said search warrants for the raids had been based on information obtained from a suspect arrested that Saturday night and charged with the murder that day‐ of Sgt. Frank Von Colin, 43‐year‐old member of the park police unit.The suspect was Hugh S. Wil Barns, 29. Mr. Rizzo said Mr. Williams had named five “coconspirators.” Two of them, Robert and Alvin Joyner, brothers, were also arrested. Mr. Rizzo said the Federal Bureau of investigation had joined the search for the three other blacks. The commissioner said that Mr. Williams had “voluntarily” told the police that he and the five others conspired to “kill some pigs” and blow up the Cobbs Creek Park guard station manned by Sergeant Von Colin.According to the authorities, a park patrolman, James Harrington was shot in the mouth near the station shortly before Sergeant Von Colin was killed by a Negro who fired five shots from a pistol. Several un exploded hand grenades were found near the station.Mr. Rizzo said the police had learned that Alvin Joyner was a member of the Black Panther party and was reported to have displayed weapons at one of its buildings.Warrant for the searches were obtained on this basis, Mr. Rizzo said, observing that the police in other cities had been criticized for the manner of raids on Panther headquarters, Accordingly, he said he had waited until he had a sound legal basis for such al raid. He named no other city, but apparently the allusion included Chicago, where two Panther leaders were killed in a pre‐dawn raid accompanied by a hail of police bullets in 1969 (Fred Hampton killing).Mr. Rizzo, who had a reputation for being one of the nation’s toughest policemen, assailed Temple University of facial’s for granting the Panthers free use of a meeting room the following Saturday, in September, for the opening session of a three‐day national conference of Panthers and other radicals.Huey P. Newton, a top Panther leader at that time was recently released from prison in California, and was scheduled to be keynote speaker. The conference has been called to prop die constitutional revisions to guarantee rights of the oppressed.Mr. Rizzo said the meeting, was fraught with the possibility of violence.In view of the Saturday night shootings, critical wounding by blacks in the same neighborhood of two more policemen the night before, and racial conflict in two mixed sections of Philadelphia, the commissioner announced these measures:¶All days off for policemen have been canceled while the “emergency” continues.¶All policemen will work 12‐ hour shifts to keep more of them on the streets.¶The police will work in pairs rather than singly in all vehicle and foot patrols.¶Isolated park stations such as the one manned by Sergeant Von Colin will be closed.Mr. Rizzo said that Mayor James H. J. Tate authorized him today to fill 599 vacancies in, the police force for which no funds had been available previously. This will bring the force to its authorized strength of 7,600.At a news conference a Panther spokesman who gave his name as Big Man and described himself as nation al minister of information charged that “the whole purpose of today’s raids was to suppress the Black Panther constitutional convention.”“We are still going forth with our plenary session,” he said. “If Rizzo wants to murder Panthers there will be Panthers around this week end. Fascism won’t stop us.”Other Panthers said they were outraged at the way the Panthers were lined up against the outside of buildings and stripped while the police searched them.An Ad Hoc Group of Concerned Organizations, saying it represented 30 black and antiwar groups, issued a statement supporting Big Man’s charges. It said the raids “were made in a climate deliberately created by the police.” Mr. Rizzo, would go on to be one of Philadelphia’s most beloved Mayor’s with a staute of him outside of Philadelphia’s Municipal Services Building. In May 2020, the statue was vandalized and on the night of June 2, the statue was removed.Research more about this great American tragedy and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event was a devastating day for all who lived in the Parishes surrounding New Orleans and the Gulf Cost of Mississippi and Alabama.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event was a devastating day for all who lived in the Parishes surrounding New Orleans and the Gulf Cost of Mississippi and Alabama. Black people were hit the worst because they had little resources to leave the areas and depended on the local government for support and the rest you know. As of today 16 years later they are being hit again what a birthday party.Hurricane Katrina was a large Category 5 Atlantic hurricane that caused over 1,800 deaths and $125 billion in damage in August 2005, particularly in the city of New Orleans and the surrounding areas. It was at the time the costliest tropical cyclone on record, and is now tied with 2017’s Hurricane Harvey. The storm was the twelfth tropical cyclone, the fifth hurricane, and the third major hurricane of the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season, as well as the fourth-most intense Atlantic hurricane on record to make landfall in the contiguous United States.Katrina originated on August 23, 2005 as a tropical depression from the merger of a tropical wave and the remnants of Tropical Depression Ten. Early the following day, the depression intensified into a tropical storm as it headed generally westward toward Florida, strengthening into a hurricane two hours before making landfall at Hallandale Beach on August 25. After briefly weakening to tropical storm strength over southern Florida, Katrina emerged into the Gulf of Mexico on August 26 and began to rapidly intensify. The storm strengthened into a Category 5 hurricane over the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico before weakening to Category 3 strength at its second landfall on August 29 over southeast Louisiana and Mississippi.Flooding, caused largely as a result of fatal engineering flaws in the flood protection system known as levees around the city of New Orleans, precipitated most of the loss of lives. Eventually, 80% of the city, as well as large tracts of neighboring parishes, were inundated for weeks. The flooding also destroyed most of New Orleans’ transportation and communication facilities, leaving tens of thousands of people who had not evacuated the city prior to landfall stranded with little access to food, shelter, or other basic necessities. The scale of the disaster in New Orleans provoked massive national and international response efforts; federal, local, and private rescue operations evacuated displaced persons out of the city over the following weeks. Multiple investigations in the aftermath of the storm concluded that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which had designed and built the region’s levees decades earlier, was responsible for the failure of the flood-control systems,[6] though federal courts later ruled that the Corps could not be held financially liable because of sovereign immunity in the Flood Control Act of 1928. The emergency response from federal, state, and local governments was widely criticized, resulting in the resignations of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) director Michael D. Brown and New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) Superintendent Eddie Compass. Many other government officials were criticized for their responses, especially New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin, Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco, and President George W. Bush, while several agencies, including the United States Coast Guard (USCG), National Hurricane Center (NHC), and National Weather Service (NWS), were commended for their actions. The NHC was especially applauded for providing accurate forecasts well in advance. Katrina was the earliest 11th named storm on record before being surpassed by Tropical Storm Kyle on August 14, 2020.Today in our History – August 28, 2005 – Hurricane Katrina hit the people of New Orleans. On August 27, the storm grew to a Category 3 hurricane. At its largest, Katrina was so wide its diameter stretched across the Gulf of Mexico.Before the storm hit land, a mandatory evacuation was issued for the city of New Orleans, which had a population of more than 480,000 at the time. Tens of thousands of residents fled. But many stayed, particularly among the city’s poorest residents and those who were elderly or lacked access to transportation. Many sheltered in their homes or made their way to the Superdome, the city’s large sports arena, where conditions would soon deteriorate into hardship and chaos.Katrina passed over the Gulf Coast early on the morning of August 29. Officials initially believed New Orleans was spared as most of the storm’s worst initial impacts battered the coast toward the east, near Biloxi, Mississippi, where winds were the strongest and damage was extensive. But later that morning, a levee broke in New Orleans, and a surge of floodwater began pouring into the low-lying city. The waters would soon overwhelm additional levees.The following day, Katrina weakened to a tropical storm, but severe flooding inhibited relief efforts in much of New Orleans. An estimated 80 percent of the city was soon underwater. By September 2, four days later, the city and surrounding areas were in full-on crisis mode, with many people and companion animals still stranded, and infrastructure and services collapsing. Congress issued $10 billion for disaster relief aid while much of the world began criticizing the U.S. government’s response.The city of New Orleans was at a disadvantage even before Hurricane Katrina hit, something experts had warned about for years, but it had limited success in changing policy. The region sits in a natural basin, and some of the city is below sea level so is particularly prone to flooding. Low-income communities tend to be in the lowest-lying areas.Just south of the city, the powerful Mississippi River flows into the Gulf of Mexico. During intense hurricanes, oncoming storms can push seawater onto land, creating what is known as a storm surge. Those forces typically cause the most hurricane-related fatalities. As Hurricane Katrina hit, New Orleans and surrounding parishes saw record storm surges as high as 19 feet.An assessment from the state of Louisiana confirmed that just under half of the 1,200 deaths resulted from chronic disease exacerbated by the storm, and a third of the deaths were from drowning. Hurricane death tolls are debated, and for Katrina, counts can vary by as much as 600. Collected bodies must be examined for cause of death, and some argue that indirect hurricane deaths, like being unable to access medical care, should be counted in official numbers.Hurricane Katrina was the costliest in U.S. history and left widespread economic impacts. Oil and gas industry operations were crippled after the storm and coastal communities that rely on tourism suffered from both loss of infrastructure and business and coastal erosion.An estimated 400,000 people were permanently displaced by the storm. Demographic shifts followed in the wake of the hurricane. The lowest-income residents often found it more difficult to return. Some neighborhoods now have fewer residents under 18 as some families chose to permanently resettle in cities like Houston, Dallas, and Atlanta. The city is also now more racially diverse, with higher numbers of Latino and Asian residents, while a disproportionate number of African-Americans found it too difficult to return.Rebuilding part of New Orleans’s hurricane defenses cost $14.6 billion and was completed in 2018. More flood systems are pending construction, meaning the city is still at risk from another large storm. A series of flood walls, levees, and flood gates buttress the coast and banks of the Mississippi River.Simulations modeled in the years after Katrina suggest that the storm may have been made worse by rising sea levels and warming temperatures. Scientists are concerned that hurricanes the size of Katrina will become more likely as the climate warms.Studies are increasingly showing that climate change makes hurricanes capable of carrying more moisture. At the same time, hurricanes are moving more slowly, spending more time deluging areas unprepared for major flooding. Research more about this great American tragedy and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!