GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is Serena Jameka Williams (born September 26, 1981) is an American professional tennis player and former world No. 1 in women’s single tennis. She has won 23 Grand Slam singles titles, the most by any player in the Open Era, and the second-most of all time behind Margaret Court (24). The Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) ranked her world No. 1 in singles on eight separate occasions between 2002 and 2017. She reached the No. 1 ranking for the first time on July 8, 2002. On her sixth occasion, she held the ranking for 186 consecutive weeks, tying the record set by Steffi Graf. In total, she has been No. 1 for 319 weeks, which ranks third in the Open Era among female players behind Graf and Martina Navratilova.Williams is widely regarded to be one of the greatest tennis players of all time. She holds the most Grand Slam titles in singles, doubles, and mixed doubles combined among active players. Her 39 Grand Slam titles put her joint-third on the all-time list and second in the Open Era: 23 in singles, 14 in women’s doubles, and two in mixed doubles. She is the most recent female player to have held all four Grand Slam singles titles simultaneously (2002–03 and 2014–15) and the third player to achieve this twice, after Rod Laver and Graf. She is also the most recent player to have won a Grand Slam title on each surface (hard, clay and grass) in one calendar year (2015). She is also, together with her older sister Venus, the most recent player to have held all four Grand Slam women’s doubles titles simultaneously (2009–10).Williams has won a record of 13 Grand Slam singles titles on hard court. Williams holds the Open Era record for most titles won at the Australian Open (7) and shares the Open Era record for most titles won at the US Open with Chris Evert (6). She also holds the records for the most women’s singles matches won at majors with 362 matches and most singles majors won since turning 30-years-old (10).Williams has won 14 Grand Slam doubles titles, all with her sister Venus, and the pair are unbeaten in Grand Slam doubles finals. As a team, she and Venus have the third most women’s doubles Grand Slam titles, behind the 18 titles of Natasha Zvereva (14 with Gigi Fernández) and the record 20 titles won by Martina Navratilova and Pam Shriver. Williams is also a five-time winner of the WTA Tour Championships in the singles division. She has also won four Olympic gold medals, one in women’s singles and three in women’s doubles—an all-time record shared with her sister, Venus. The arrival of the Williams sisters has been credited with ushering in a new era of power and athleticism on the women’s professional tennis tour. She is ranked at No. 7 in the world by the WTA as of February 22, 2021. Earning almost $29 million in prize money and endorsements, Williams was the highest paid female athlete in 2016. She repeated this feat in 2017 when she was the only woman on Forbes’ list of the 100 highest paid athletes with $27 million in prize money and endorsements. She has won the ‘Laureus Sportswoman of the Year’ award four times (2003, 2010, 2016, 2018), and in December 2015, she was named Sportsperson of the Year by Sports Illustrated magazine. In 2019, she was ranked 63rd in Forbes’ World’s Highest-Paid Athletes list.Today in our History – September 26, 1981 – Serena Jameka Williams was born.One of the world’s greatest tennis players, Serena Jameka Williams was born on September 26, 1981 in Saginaw, Michigan. Williams storybook tennis career evolves into more dominance of the sport with each passing chapter.She made history as on September 11, 1999, when as a young seventeen-year-old, she became the second African American woman to win the US Open, following the historic Althea Gibson who won the US Open in 1957 and 1958. She and her older sister Venus Williams have been leaders in the sport during the 21st century.Serena and her sister Venus have represented the United States well in the Olympic Games, winning more gold medals than any other women in tennis. Research more about this great American champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

Tag: Brandon hardison

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American actor and filmmaker.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American actor and filmmaker. He portrayed Andy on TV’s The Amos ‘n’ Andy Show and directed films including the 1941 race film The Blood of Jesus. He was a pioneering African-American film producer and director.Today in our History – September 25, 1991 – Spencer Williams’s 1942 – movie Blood of Jesus is among the third group of 25 films added to the Library of Congress National Film Registry.Williams (who was sometimes billed as Spencer Williams Jr.) was born in Vidalia, Louisiana, where the family lived on Magnolia Street. As a youngster, he attended Wards Academy in Natchez, Mississippi. He moved to New York City when he was a teenager and secured work as call boy for the theatrical impresario Oscar Hammerstein. During this period, he received mentoring as a comedian from the African American vaudeville star Bert Williams. Williams studied at the University of Minnesota and served in the U.S. Army during and after World War I, rising to the rank of sergeant major. During his military service, Williams traveled the world, serving as General Pershing’s bugler while in Mexico before he was promoted to camp sergeant major. In 1917, Williams was sent to France to do intelligence work there. After World War I, Williams continued his military career; he was part of a unit whose job was to create war plans for the Southwestern United States, in case they might ever be needed. He arrived in Hollywood in 1923 and his involvement with films began by assisting with works by Octavus Roy Cohen. Williams snagged bit roles in motion pictures, including a part in the 1928 Buster Keaton film Steamboat Bill, Jr. He found steady work after arriving in California apart from a short period in 1926 where there were no roles for him; he then went to work as an immigration officer. In 1927, Williams was working for the First National Studio, going on location to Topaz, Arizona to shoot footage for a film called The River. In 1929, Williams was hired by producer Al Christie to create the dialogue for a series of two-reel comedy films with all-black casts. Williams gained the trust of Christie and was eventually appointed the responsibility to create The Melancholy Dame. This film is considered the first black talkie. The films, which played on racial stereotypes and used grammatically tortured dialogue, included The Framing of the Shrew, The Lady Fare, Melancholy Dame, (first Paramount all African-American cast “talkie”), Music Hath Charms, and Oft in the Silly Night. Williams wore many hats at Christie’s; he was a sound technician, wrote many of the scripts and was assistant director for many of the films. He was also hired to cast African-Americans for Gloria Swanson’s Queen Kelly (1928) and produced the silent film Hot Biskits, which he wrote and directed, in the same year. Williams also did some work for Columbia as the supervisor of their Africa Speaks recordings. Williams was also active in theater productions, taking a role in the all African-American version of Lulu Belle in 1929. Due to the pressures of the depression coupled with the lowering demand for black short films, Williams and Christie separated ways. Williams struggled for employment during the years of the Depression and would only occasionally be cast in small roles. Movies included a brief appearance in Warner Bros.’ gangster film The Public Enemy (1931) in which he was uncredited. By 1931, Williams and a partner had founded their own movie and newsreel company called the Lincoln Talking Pictures Company. The company was self-financed. Williams, who had experience in sound technology, built the equipment, including a sound truck, for his new venture. During the 1930s, Williams secured small roles in race films, a genre of low-budget, independently-produced films with all-black casts that were created solely for exhibition in racially segregated theaters. Williams also created two screenplays for race film production: the Western film Harlem Rides the Range and the horror-comedy Son of Ingagi, both released in 1939. After a three-year hiatus from show business during the Great Depression, Williams began finding work again. He was cast in Jed Buell’s Black westerns between the years of 1938 and 1940. He played character roles in such black westerns as Harlem on the Prairie (1937), Two-Gun Man from Harlem (1938), The Bronze Buckaroo (1939), and Harlem Rides the Range (1939). Buell’s idea to hire Williams revolved around his ability to captivate the audience with his showmanship. Williams’ involvement in these films gave him a valuable learning experience in the black film genre. Although these films were considered to be crude films in their creation, Williams got the opportunity to start directing here and there even though his control was scarce. Alfred N. Sack, whose San Antonio, later Dallas, Texas based company Sack Amusement Enterprises produced and distributed race films, was impressed with Williams’ screenplay for Son of Ingagi and offered him the opportunity to write and direct a feature film. At that time, the only African American filmmaker was the self-financing writer/director/producer Oscar Micheaux.Besides being a film production company, Sack also had interests in movie theaters. He had more than one name for his ventures; they were also known as Sack Attractions and Harlemwood Studios. Sack produced films under all of his company’s various names. With his own film projector, Williams began traveling in the southern US, showing his films to audiences there. During this time, he met William H. Kier, who was also traveling the same circuit showing films. The two formed a partnership and produced some motion pictures, training films for the Army Air Forces, as well as a film for the Catholic diocese of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Williams’s resulting film, The Blood of Jesus (1941), was produced by his own company, Amegro, on a $5,000 budget using non-professional actors for his cast. It was the first film he directed and Williams also wrote the screenplay. A religious fantasy about the struggle for a dying’ Christian woman’s soul, the film was a major commercial success.[5] Sack declared The Blood of Jesus was “possibly the most successful” race film ever made, and Williams was invited to direct additional films for Sack Amusement Enterprises.There were problems that the producers faced with the technical aspects of the film. Despite these issues, Williams used his expertise to help with the camera, special effects and symbolism. The themes that he used in the film helped the film receive praise. Religious themes, including Protestantism and Southern Baptist, helped underpin the narrative. Despite the success that The Blood of Jesus enjoyed, Williams’s next film was considered an epic failure and seen by few. The attempt to create a wartime drama resulted in the film Marching On! (1943). Set with World War II as the backdrop, the film was badly made and was left in the shadow of the Army financed film The Negro Soldier (1944). Most of the narrative seen in Marching On was influenced by William’s own time in the army during World War I. Due to an uneven and uninteresting plot the film was seen as a dud and was unable to garner the social acknowledgment that Williams had hoped it would receive. Williams’s next film, Go Down Death (1944), is considered to be on par with The Blood of Jesus as the best overall primitive film that Williams made. Just like that movie, Williams directed, wrote the screenplay, and acted in the film. He gained inspiration for the story of the screenplay from the fable of the same name, written by the poet James Weldon Johnson. The years after his most successful films and the years preceding his mainstream success with Amos ‘n’ Andy found Williams in another career rut. Rather than continuing to make film in his primitive format, he began to try to follow mainstream Hollywood conventions. Williams’s attempts to conform in the film industry actually began to bog down his stories and his otherwise original films.In the next six years, Williams directed Brother Martin: Servant of Jesus (1942), Marching On! (1943), Go Down Death (1944), Of One Blood (1944), Dirty Gertie from Harlem U.S.A. (1946), The Girl in Room 20 (1946), Beale Street Mama (1947) and Juke Joint (1947). After working ten years in Dallas, Williams returned to Hollywood in 1950. Following the production of Juke Joint, Williams relocated to Tulsa, Oklahoma, where he joined Amos T. Hall in founding the American Prior to his involvement with Amos ‘n’ Andy, Williams was immensely popular among the African-American audiences. U.S. radio comedians Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, who cast Williams as Andy, were able to claim that they were the ones who found Williams and gave him the chance to be seen in the limelight because he was virtually unknown amongst the white audience. In 1948, Gosden and Correll were planning to take their long-running comedy program Amos ‘n Andy to television. The program focused on the misadventures of a group of African Americans in the Harlem section of New York City. Gosden and Correll were white, but played the black lead characters using racially stereotypical speech patterns. They had previously played the roles in blackface make-up for the 1930 film Check and Double Check, but the television version used an African American cast. Gosden and Correll conducted an extensive national talent search to cast the television version of Amos ‘n Andy. News of the search reached Tulsa, where Williams was sought out by a local radio station that was aware of his previous work in race films. A Catholic priest, who was a radio listener and a friend, was the key to the whereabouts of Williams. He was working in Tulsa as the head of a vocational school for veterans when the casting call went out. Williams successfully auditioned for Gosden and Correll, and he was cast as Andrew H. Brown. Williams was joined in the cast by New York theater actor Alvin Childress, who was cast as Amos, and vaudeville comedian Tim Moore, who was cast as their friend George “Kingfish” Stevens. When Williams accepted the role of Andy, he returned to a familiar location; the CBS studios were built on the former site of the Christie Studios. Until Amos ‘n’ Andy, Williams had never worked in television. Amos ‘n Andy was the first U.S. television program with an all-black cast, running for 78 episodes on CBS from 1951 to 1953. However, the program created considerable controversy, with the NAACP going to federal court to achieve an injunction to halt its premiere. In August 1953, after the program had recently left the air, there were plans to turn it into a vaudeville act with Williams, Moore and Childress reprising their television roles. It is not known if there were any performances. After the show completed its network run, CBS syndicated Amos ‘n Andy to local U.S. television stations and sold the program to television networks in other countries. The program was eventually pulled from release in 1966, under pressure from civil rights groups that stated it offered a negatively distorted view of African American life. The show would not be seen on nationwide television again until 2012. While the show was still in production, Williams and Freeman Gosden clashed over the portrayal of Andy, with Gosden telling Williams he knew how Amos ‘n’ Andy were meant to talk. Gosden never visited the set again. Williams, along with television show cast members Tim Moore, Alvin Childress, and Lillian Randolph and her choir, began a US tour as “The TV Stars of Amos ‘n’ Andy” in 1956. CBS considered this a violation of their exclusivity rights for the show and its characters; the tour came to a premature end. Williams, Moore, Childress and Johnny Lee, performed a one-night show in Windsor, Ontario in 1957, apparently without any legal action being taken. Williams returned to work in stage productions. In 1958, he had a role in the Los Angeles production of Simply Heavenly; the play had a successful New York run. His last credited role was as a hospital orderly in the 1962 Italian horror production L’Orribile Segreto del Dottor Hitchcock. After his failed attempts to find success in the film industry once again, Williams decided to fully retire and began to live off of his pension that he was receiving from his time with the US Military. Williams died of a kidney ailment on December 13, 1969, at the Sawtelle Veterans Administration Hospital in Los Angeles, California. He was survived by his wife, Eula. At the time of his death, news coverage focused solely on his work as a television actor, since few white filmgoers knew of his race films. The New York Times obituary for Williams cited Amos ‘n Andy but made no mention of his work as a film director. A World War I veteran, he is buried at Los Angeles National Cemetery. When friends and family from Vidalia, Louisiana were interviewed for a local newspaper article in 2001, he was remembered as a happy person, who was always singing or whistling and telling jokes. His younger cousins also recalled his generosity with them for “candy money”; just as he was seen on television as Andy, he always had his cigar. On March 31, 2010, the state of Louisiana voted to honor Williams and musician Will Haney, also from Vidalia, in a celebration on May 22 of that year. Despite his contribution as a pioneer in black American film of the 1930s and the 1940s, Williams was almost completely forgotten after his death. While even to this day his legacy doesn’t enjoy the same recognition and praise that other black film pioneers such as Oscar Micheaux, in his time, Williams was considered one of the few successful black Americans involved in the film industry during this period. Recognition for Williams’ work as a film director came years after his death, when film historians began to rediscover the race films. Some of Williams’ films were considered lost until they were located in a Tyler, Texas, warehouse in 1983. One film directed by Williams, his 1942 feature Brother Martin: Servant of Jesus, is still considered lost. There were seven films in total; they were originally shown at small gatherings throughout the South. Most film historians consider The Blood of Jesus to be Williams’ crowning achievement as a filmmaker. Dave Kehr of The New York Times called the film “magnificent” and Time magazine counted it among its “25 Most Important Films on Race.” In 1991, The Blood of Jesus became the first race film to be added to the U.S. National Film Registry. Film critic Armond White named both The Blood of Jesus and Go Down Death as being “among the most spiritually adventurous movies ever made. They conveyed the moral crisis of the urban/country, blues/spiritual musical dichotomies through their documentary style and fable-like narratives.” However, Williams’ films have also been the subject of criticism. Richard Corliss, writing in Time magazine, stated: “Aesthetically, much of Williams’ work vacillates between inert and abysmal. The rural comedy of Juke Joint is logy, as if the heat had gotten to the movie; even the musical scenes, featuring North Texas jazzman Red Calhoun, move at the turtle tempo of Hollywood’s favorite black of the period, Stepin Fetchit. And there were technical gaffes galore: in a late-night scene in Dirty Gertie, actress Francine Everett clicks on a bedside lamp and the screen actually darkens for a moment before full lights finally come up. Yet at least one Williams film, his debut Blood of Jesus (1941), has a naive grandeur to match its subject.” It should also be realized that Williams often worked on a very meager budget. The Blood of Jesus was filmed for a cost of $5,000; most black films of that era had budgets of double and triple that amount. Williams began writing a book about his 55 years in show business in 1959. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an attorney in Tulsa, Oklahoma, who is most notably known for defending the survivors of the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an attorney in Tulsa, Oklahoma, who is most notably known for defending the survivors of the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. He was also father to the venerable civil rights advocate and historian John Hope Franklin.Today in our History – September 24, 1960 – Buck Franklin (May 6, 1879 – September 24, 1960) died.Buck Franklin was an attorney in Tulsa, Oklahoma, who is most notably known for defending the survivors of the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. He was also father to the venerable civil rights advocate and historian John Hope Franklin.Franklin was born the seventh of ten on May 6, 1879, near the town of Homer in Pickens County, Chickasaw Nation, Indian Territory (currently Oklahoma). He was named Buck in honor of his grandfather who had been a slave and purchased the freedom of his family and himself. There is speculation that the true origins of the Franklins’ freedom came when Buck Franklin’s father, David Franklin, escaped from his plantation and changed his name early in the Civil War.Practicing law as a young man in the predominantly white town of Ardmore, Oklahoma, he faced racial prejudice and saw major flaws in the white judicial system. In one instance, he was literally silenced in a Louisiana courtroom because of his race. In response to this, he decided to focus on practicing law within African American communities and moved to the all-black town of Rentiesville, Oklahoma, where he would marry Mollie Parker Franklin and start his own family in 1915. Franklin later moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma, with his family in 1921.In Tulsa, during 1921, racial tensions were extremely high. The town had one of the most affluent black communities in the nation—the Greenwood District, also known as ‘Black Wall Street’ which created a sharp divide between blacks and whites. In May of 1921, a young black man named Dick Rowland was in an elevator with a white woman named Sarah Page. It was alleged that he attempted to assault her, and he was promptly arrested. There was an altercation between a group of black and white people at the courthouse which, in the next twenty-four hours, would escalate to a massive one-day race riot that left approximately three hundred dead, much of the black population imprisoned, and the Greenwood District in ruins. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies and make it a champion day!Franklin and his family had managed to survive the riot. The Tulsa City Council, however, in the aftermath of the carnage, passed an ordinance that prevented the black people of Tulsa from rebuilding their community. The city planned instead to rezone the area from a residential to a commercial district. Franklin led the legal battle against this ordinance and sued the city of Tulsa before the Oklahoma Supreme Court, where he won. As a consequence, black Tulsa residents could and did begin the reconstruction of their nearly destroyed community.Franklin went on to write his own autobiography but would pass away on September 24, 1960, in Oklahoma, unable to see its final publication. Of his four children, John Hope Franklin would become a prominent historian and black intellectual of this time period. He contributed to the Brown v. Board of Education case and participated in the 1965 march for voting rights in Selma, Alabama. John Hope Franklin and his son would finalize B.C. Franklin’s autobiography, My Life and an Era: The Autobiography of Buck Colbert Franklin. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American professional baseball outfielder.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American professional baseball outfielder. He began his 19-year Major League Baseball (MLB) career with the 1961 Chicago Cubs but spent the majority of his big league career as a left fielder for the St. Louis Cardinals. He was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1985 and the St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Fame in 2014. He was a special instructor coach for the St. Louis Cardinals.He was best known for his base stealing, breaking Ty Cobb’s all-time major league career steals record and Maury Wills’s single-season record. He was an All-Star for six seasons and a National League (NL) stolen base leader for eight seasons. He led the NL in doubles and triples in 1968. He also led the NL in singles in 1972, and was the runner-up for the NL Most Valuable Player Award in 1974.Today in our History – September 23, 1979 – Louis Clark Brock (June 18, 1939 – September 6, 2020) stole a record of 935 bases and became the all-time major league record holder.If it’s been said once, it’s been said a million times. The Cardinals’ acquisition of outfielder Lou Brock from the Chicago Cubs on June 15, 1964, ranks as perhaps the greatest steal in baseball history. St. Louis traded pitchers Ernie Broglio and Bobby Shantz and outfielder Doug Clemens in exchange for Brock and pitchers Jack Spring and Paul Toth.Over the course of his career with the Cardinals, Brock established himself as the most prolific base stealer in baseball history to that time. His 938 stolen bases stood as the major league record until Rickey Henderson bettered the mark in 1991. Brock’s total remains the National League standard, and he holds the major league record with 12 seasons of 50 or more steals.Brock led the N.L. in thefts on eight occasions (1966 to 1969 and 1971 to 1974). He set the season record with 118 in 1974, bettering the mark of 104 by Maury Wills during the 1962 campaign. In 1978, the N.L. announced that its annual stolen base leader would receive the Lou Brock Award, making Brock the first active player to have an award named after him.But Brock was more than a base burglar. He was a career .293 batter with 3,023 hits. Seven times he batted at a .300 or better clip. In 1967, Brock slugged 21 home runs and had 76 RBI from the leadoff spot. He also had 52 stolen bases to become the first player in baseball history with 20 homers and 50 steals.The following year, Brock topped the N.L. in doubles (46), triples (14) and stolen bases (62), the first player in the Senior Circuit to do so since Honus Wagner of the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1908. Brock joined the 3,000-hit club Aug. 13, 1979, with a fourth-inning single off Dennis Lamp of the Chicago Cubs at Busch Stadium.Brock paid immediate dividends in St. Louis, batting .348 for the balance of the 1964 season and propelling the Cardinals from eighth place in the N.L. to a World Championship over the New York Yankees. The Cardinals won the World Series again in 1967 over the Boston Red Sox and were N.L. champions in 1968. Brock was at his best in postseason play.His .391 career batting average (34-for-87) is a World Series record, while his 14 stolen bases are tied for the most all time with Eddie Collins of the Philadelphia Athletics and Chicago White Sox.On the Cardinals’ career lists, Brock ranks first in stolen bases (888 – Vince Coleman is second with 549); second in games (2,289), at-bats (9,125), runs (1,427), hits (2,713), doubles (434) and total bases (3,776); fourth in triples (121); fifth in walks (681); and eighth in RBI (814). He was a six-time N.L. All-Star.Brock has remained active in baseball since retiring as a player following the 1979 season. He worked in the Cardinals’ broadcast booth from 1981 to 1984; was a baserunning consultant for the Minnesota Twins in 1987,Los Angeles Dodgers in 1988 and Montreal Expos in 1993; and has served as a special instructor for the Cardinals (baserunning and outfield play) since 1995. He was a first-ballot Hall of Fame inductee in 1985. Research more about this great American and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African-American artist and teacher who lived and worked in Washington, D.C., and is now recognized as a major American painter of the 20th century.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an African-American artist and teacher who lived and worked in Washington, D.C., and is now recognized as a major American painter of the 20th century.Thomas is best known for the “exuberant”, colorful, abstract paintings that she created after her retirement from a 35-year career teaching art at Washington’s Shaw Junior High School.Thomas, who is often considered a member of the Washington Color School of artists but alternatively classified by some as an Expressionist, was the first graduate of Howard University’s Art department, and maintained connections to that university through her life.She achieved success as an African-American female artist despite the segregation and prejudice of her time.Thomas’s reputation has continued to grow since her death. Her paintings are displayed in notable museums and collections, and they have been the subject of several books and solo museum exhibitions. In 2019, Thomas’s 1970 painting, A Fantastic Sunset, sold at a Christie’s auction for $2.6 million.Today in our History – September 22, 1891 – Alma Woodsey Thomas was born.During the 1960s Alma Thomas emerged as an exuberant colorist, abstracting shapes and patterns from the trees and flowers around her. Her new palette and technique—considerably lighter and looser than in her earlier representational works and dark abstractions—reflected her long study of color theory and the watercolor medium.Red Sunset, Old Pond Concerto [SAAM, 1977.48.5] emphasizes the intensity of a sunset as it overtakes a landscape, penetrating layers of greenery to strike darkening water. Broken rows of color pats, a hallmark of her mature style, alternate with emphatic vertical bands.Their irregular intervals create a visual rhythm akin to music, while dappled reds, greens, and blue-blacks orchestrate subtle nuances and dramatic contrasts. Thomas frequently talked about “watching the leaves and flowers tossing in the wind as though they were singing and dancing.” She also liked to imagine seeing natural forms from a plane. Her lyrical interpretation of a pond at sunset suggests a blending of these two perspectives.As a black woman artist, Thomas encountered many barriers; she did not, however, turn to racial or feminist issues in her art, believing rather that the creative spirit is independent of race or gender. In Washington, D.C., where she lived and worked after 1921, Thomas became identified with Morris Louis, Gene Davis, and other Color Field painters active in the area since the 1950s. Like them, she explored the power of color and form in luminous, contemplative paintings.Lynda Roscoe Hartigan African-American Art: 19th and 20th-Century Selections (brochure. Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art)”Man’s highest aspirations come from nature. A world without color would seem dead. Color is life. Light is the mother of color. Light reveals to us the spirit and living soul of the world through colors.”—Press Release, Columbus Museum of Arts and Sciences, 1982, for an exhibition entitled A Life in Art: Alma Thomas 1891–1978, Vertical File, Library, National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.Alma Thomas began to paint seriously in 1960, when she retired from her thirty-eight year career as an art teacher in the public schools of Washington, D.C. In the years that followed she would come to be regarded as a major painter of the Washington Color Field School.Born on September 22, 1891, in Columbus, Georgia, Thomas was the eldest of four daughters. Her father worked in a church and her mother was a seamstress and homemaker. Thomas’s family was well respected in Columbus, and she and her sisters grew up in comfortable surroundings. The family lived in a large Victorian house high on a hill overlooking the town where Thomas spent her childhood observing the beauty and color of nature. In 1907, when Thomas was fifteen years old, her father moved the family to Washington, D.C. She enrolled in Howard University, and in 1924 became the first graduate of its newly formed art department. Thomas’s teacher and mentor, James V. Herring, granted her use of his private art library, from which she gained a thorough background in art history. A decade later, she earned a Master of Arts degree in education from Columbia University.During the 1950s Thomas attended art classes at American University in Washington. She studied painting under Joe Summerford, Robert Gates, and Jacob Kainen, and developed an interest in color and abstract art. Throughout her teaching career she painted and exhibited academic still lifes and realistic paintings in group shows of African-American artists. Although her paintings were competent, they were never singled out for individual recognition.Suffering from the pain of arthritis at the time of her retirement, she considered giving up painting. When Howard University offered to mount a retrospective of her work in 1966, however, she wanted to produce something new. From the window of her house she enjoyed watching the ever-changing patterns that light created on her trees and flower garden. So inspired, her new paintings passed through an expressionist period, followed by an abstract one, to finally a nonobjective phase.Many of Thomas’s late-career paintings were watercolors in which bold splashes of color and large areas of white paper combine to create remarkably fresh effects, often accented with brush strokes of India ink.Although Thomas progressed to painting in acrylics on large canvases, she continued to produce many watercolors that were studies for her paintings. Thomas’s personalized mature style consisted of broad, mosaic-like patches of vibrant color applied in concentric circles or vertical stripes. Color was the basis of her painting, undeniably reflecting her life-long study of color theory as well as the influence of luminous, elegant abstract works by Washington-based Color Field painters such as Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, and Gene Davis.Thomas was in her eighth decade of life when she produced her most important works. Earliest to win acclaim was her series of Earth paintings—pure color abstractions of concentric circles that often suggest target paintings and stripes. Done in the late 1960s, these works bear references to rows and borders of flowers inspired by Washington’s famed azaleas and cherry blossoms. The titles of her paintings often reflect this influence. In these canvases, brilliant shades of green, pale and deep blue, violet, deep red, light red, orange, and yellow are offset by white areas of untouched raw canvas, suggesting jewel-like Byzantine mosaics.Man’s landing on the moon in 1969 exerted a profound influence on Thomas, and provided the theme for her second major group of paintings. In 1969 she began the Space or Snoopy series so named because “Snoopy” was a term astronauts used to describe a space vehicle used on the moon’s surface. Like the Earth series these paintings also evoke mood through color, yet several allude to more than a color reference. In Snoopy Sees a Sunrise of 1970, she placed a circular form within the mosaic patch of colors and accented it with curved bands of light colors. Blast Off depicts an elongated triangular arrangement of dark blue patches rising dramatically and evocatively against a background of pale pinks and oranges. The majority of Thomas’s Space paintings are large sparkling works with implied movement achieved through floating patterns of broken colors against a white background.In her last paintings, Thomas employed her characteristic short bars of color and impasto technique. The tones, however, became more subdued, and the formerly vertical and horizontal accents of Thomas’s brush strokes became more diverse in movement, and included diagonals, diamond shapes, and asymmetrical surface patterns. During the artist’s final years, the crippling effects of arthritis prevented her from painting as often as she wanted.Alma Thomas never married, and lived in the same house her father bought in downtown Washington in 1907. The final years of her life brought awards and recognition. In 1972 she was honored with one-woman exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art and at the Corcoran Gallery of Art; that same year one of her paintings was selected for the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Before her death in 1978, Thomas had achieved national recognition as a major woman artist devoted to abstract painting. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM , FBF – Today’s American Champion was a French writer, poet, philosopher, and literary critic from Martinique.

GM , FBF – Today’s American Champion was a French writer, poet, philosopher, and literary critic from Martinique. He is widely recognised as one of the most influential figures in Caribbean thought and cultural commentary and Francophone literature.Today in our History – September 21, 1928 – Edouard Glissant (21 September 1928 – 3 February 2011) was born.Édouard Glissant was born in Sainte-Marie, Martinique. He studied at the Lycée Schœlcher, named after the abolitionist Victor Schœlcher, where the poet Aimé Césaire had studied and to which he returned as a teacher. Césaire had met Léon Damas there; later in Paris, France, they would join with Léopold Senghor, a poet and the future first president of Senegal, to formulate and promote the concept of negritude. Césaire did not teach Glissant, but did serve as an inspiration to him (although Glissant sharply criticized many aspects of his philosophy); another student at the school at that time was Frantz Fanon.Glissant left Martinique in 1946 for Paris, where he received his PhD, having studied ethnography at the Musée de l’Homme and History and philosophy at the Sorbonne. He established, with Paul Niger, the separatist Front Antillo-Guyanais pour l’Autonomie party in 1959, as a result of which Charles de Gaulle barred him from leaving France between 1961 and 1965. He returned to Martinique in 1965 and founded the Institut martiniquais d’études, as well as Acoma, a social sciences publication. Glissant divided his time among Martinique, Paris and New York; since 1995, he was Distinguished Professor of French at the CUNY Graduate Center. Before his tenure at CUNY Graduate Center, he was a professor at Louisiana State University in the Department of French and Francophone Studies from 1988 to 1993. In January 2006, Glissant was asked by Jacques Chirac to take on the presidency of a new cultural centre devoted to the history of slave trade.Shortlisted for the Nobel Prize in 1992, when Derek Walcott emerged as the recipient, Glissant was the pre-eminent critic of the Négritude school of Caribbean writing and father-figure for the subsequent Créolité group of writers that includes Patrick Chamoiseau and Raphaël Confiant. While Glissant’s first novel portrays the political climate in 1940s Martinique, through the story of a group of young revolutionaries, his subsequent work focuses on questions of language, identity, space, history, and knowledge and knowledge production.For example, in his text Poetics of Relation, Glissant explores the concept of opacity, which is the lack of transparency, the untransability, the unknowability. And for this reason, opacity has the radical potentiality for social movements to challenge and subvert systems of domination. Glissant demands the “right to opacity,” indicating the oppressed—which have historically been constructed as the Other—can and should be allowed to be opaque, to not be completely understood, and to simply exist as different. The colonizer perceived the colonized as different and unable to be understood, thereby constructing the latter as the Other and demanding transparency so that the former could somehow fit them into their cognitive schema and so that they could dominate them. However, Glissant rejects this transparency and defends opacity and difference because other modes of understanding do exist. That is, Glissant calls for understanding and accepting difference without measuring that difference to an “ideal scale” and comparing and making judgements, “without creating a hierarchy”—as Western thought has done.In the excerpt from Poetics of Relation, “The Open Boat”, Glissant’s imagery was particularly compelling when describing the slave experience and the linkage between a slave and the homeland and the slave and the unknown. This poem paralleled Dionne Brand’s book in calling the “Door of No Return” an Infinite Abyss. This image conveys emptiness sparked by unknown identity as it feels deep and endless. “The Open Boat” also discussed the phenomenon of “falling into the belly of the whale” which elicits many references and meanings. This image parallels the Biblical story of Jonah and the Whale, realizing the gravity of biblical references as the Bible was used as justification for slavery. More literally, Glissant related the boat to a whale as it “devoured your existence”. As each word a poet chooses is specifically chosen to aid in furthering the meaning of the poem, the word “Falling” implies an unintentional and undesirable action. This lends to the experience of the slaves on the ship as they were confined to an overcrowded, filthy, and diseased existence among other slaves, all there against their will. All of Glissant’s primary images in this poem elicit the feeling of endlessness, misfortune, and ambiguity, which were arguably the future existence of the slaves on ships to “unknown land”.Slave ships did not prioritize the preservation of cultural or individual history or roots, but rather only documented the exchange rates for the individuals on the ship, rendering slaves mere possessions and their histories part of the abyss. This poem also highlights an arguable communal feeling through shared relationship to the abyss of personal identity. As the boat is the vessel that permits the transport of known to unknown, all share the loss of sense of self with one another. The poem also depicts the worthlessness of slaves as they were expelled from their “womb” when they no longer required “protection” or transport from within it. Upon losing exchange value, slaves were expelled overboard, into the abyss of the sea, into another unknown, far from their origins or known land.This “relation” that Glissant discusses through his critical work conveys a “shared knowledge”. Referring back to the purpose of slaves—means of monetary and property exchange—Glissant asserts that the primary exchange value is in the ability to transport knowledge from one space or person to another—to establish a connection between what is known and unknown.Glissant’s development of the notion of antillanité seeks to root Caribbean identity firmly within “the Other America” and springs from a critique of identity in previous schools of writing, specifically the work of Aimé Césaire, which looked to Africa for its principal source of identification. Glissant is notable for his attempt to trace parallels between the history and culture of the Creole Caribbean and those of Latin America and the plantation culture of the American south, most obviously in his study of William Faulkner. Generally speaking, Glissant’s thinking seeks to interrogate notions of centre, origin and linearity, embodied in his distinction between atavistic and composite cultures, which has influenced subsequent Martinican writers’ trumpeting of hybridity as the bedrock of Caribbean identity and their “creolised” approach to textuality. As such, he is both a key (though underrated) figure in postcolonial literature and criticism, but also he often pointed out that he was close to two French philosophers, Félix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze, and their theory of the rhizome.Glissant died in Paris, France, on 3 Februay 2011, at the age of 82. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is s an American actress, producer, and political activist.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is s an American actress, producer, and political activist. She has been named one of the most versatile and accomplished actors of her generation. She has been nominated for an Academy Award, two Grammy Awards, and eighteen Emmy Awards (winning four); additionally, she received a Golden Globe Award and three Screen Actors Guild Awards. In 2020, The New York Times ranked Woodard seventeenth on its list of “The 25 Greatest Actors of the 21st Century”. She is also known for her work as a political activist and producer. Woodard is a founder of Artists for a New South Africa, an organization devoted to advancing democracy and equality in that country. She is a board member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Today in our History – September 20, 1987 – Alfre Woodard wins her second Emmy for outstanding guest performance in the dramatic series L.A. Law. (1987).Woodard began her acting career in theater. After her breakthrough role in the Off-Broadway play For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf (1977), she made her film debut in Remember My Name (1978). In 1983, she won major critical praise and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role in Cross Creek. In the same year, Woodard won her first Primetime Emmy Award for her performance in the NBC drama series Hill Street Blues. Later in the 1980s, Woodard had leading Emmy Award-nominated performances in a number of made for television movies, and another Emmy-winning role as a woman dying of leukemia in the pilot episode of L.A. Law. She also starred as Dr. Roxanne Turner in the NBC medical drama St. Elsewhere, for which she was nominated for a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series in 1986, and for Guest Actress in 1988.In the 1990s, Woodard starred in films such as Grand Canyon (1991), Heart and Souls (1993), Crooklyn (1994), How to Make an American Quilt (1995), Primal Fear (1996), and Star Trek: First Contact (1996). She also drew critical praise for her performances in the independent dramas Passion Fish (1992), for which she won an Independent Spirit Award and was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actress, as well as Down in the Delta (1998). For her lead role in the HBO film Miss Evers’ Boys (1997), Woodard won Golden Globe, Emmy, Screen Actors Guild, and several other awards. In later years, she has appeared in several blockbusters, like K-PAX (2001), The Core (2003), and The Forgotten (2004), starred in independent films and won her fourth Emmy Award for The Practice in 2003.From 2005 to 2006, Woodard starred as Betty Applewhite in the ABC comedy-drama series Desperate Housewives and later starred in several short-lived series. She appeared in the critically acclaimed films 12 Years a Slave (2013), Juanita (2019), Clemency (2019, for which she was nominated for a BAFTA Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role) as well as the box office hits Annabelle (2014), and Captain America: Civil War (2016), and the remake of The Lion King (2019).Woodard was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma to Constance, a homemaker, and Marion H. Woodard, an entrepreneur and interior designer. She is the youngest of three children. Woodard attended Bishop Kelley High School, a private Catholic school in Tulsa, graduating from there in 1970. She studied drama at Boston University, from which she graduated. Woodard made her professional theater debut in 1974 on Washington, D.C.’s Arena Stage. In 1976, she moved to Los Angeles, California. She later said, “When I came to L.A., people told me there were no film roles for black actors. I’m not a fool. I know that. But I was always confident that I knew my craft.”Her breakthrough role was in the Off-Broadway play For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf in 1977. The next year, Woodard made her film debut in Remember My Name, a thriller written and directed by Alan Rudolph. In the same year, she had a leading role in The Trial of the Moke, a Great Performances television movie co-starring Samuel L. Jackson.In the 1990s, Woodard also continued her work in television, earning considerable acclaim for her performances. For The Piano Lesson (1995), a Hallmark Hall of Fame movie, she won her first Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Miniseries or Television Movie, as well as being nominated for another Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Miniseries or a Movie. In the next year, she received a Primetime Emmy nomination for her performance as the Queen in the critically acclaimed Hallmark miniseries, Gulliver’s Travels, based on the classic Jonathan Swift novel. In 1997, she had the leading roles in both The Member of the Wedding (based on the novel by Carson McCullers) and Miss Evers’ Boys (on HBO). Her performance as the title character in the latter film, as a nurse who consoled many of the subjects of the notorious 1930s Tuskeegee Study of Untreated Blacks with Syphilis, earned widespread critical acclaim, sweeping all television awards in the Outstanding Lead Actress in a Miniseries or Movie category, including Primetime Emmy (besting nominees Meryl Streep, Helen Mirren, Glenn Close, and Stockard Channing), Golden Globe, Satellite, NAACP, CableACE, and Screen Actors Guild Awards. In the 2000s, Woodard’s film career showcased her versatility in a range of genres, including the ensemble comedy-drama What’s Cooking? (2000), the romantic drama Love & Basketball (2000) as the lead character’s mother, science fiction films K-PAX (2001), The Core (2003), and The Forgotten (2004), the biographical drama Radio (2003), comedies The Singing Detective (2003) and Beauty Shop (2005), the romantic drama Something New (2006), and the dance-musical Take the Lead (2006). Woodard also was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for her performance as a drug addict in the Holiday Heart (2000). In addition, she performed voice work in a variety of feature and television documentaries, as well as a voice role in Walt Disney’s Dinosaur. The film was a financial success, grossing over $349 million worldwide. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American physician and politician.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American physician and politician. She served as the 4th elected non-voting Delegate from the United States Virgin Islands’s at-large district to the United States House of Representatives from 1997 until 2015.Today in our History – September 19, 1945 – Donna Marie Christian-Christensen, formerly Donna Christian-Green was born.Donna Marie Christian-Christensen, the non-voting delegate from the U.S. Virgin Islands to the United States House of Representatives, was born in Teaneck, Monmouth Country, New Jersey on September 19, 1945 to the late Judge Almeric Christian and Virginia Sterling Christian. Christensen attended St. Mary’s College in Notre Dame, Indiana, where she received her Bachelor of Science in 1966. She then earned her M.D. degree from George Washington University School of Medicine in Washington, D.C. in 1970. Christensen began her medical career in the U.S. Virgin Islands in 1975 as an emergency room physician at St. Croix Hospital. Between 1987 and 1988 she was medical director of the St. Croix Hospital and from 1988 to 1994 she was Commissioner of Health for the Virgin Island. During the entire period from 1977 to l996 Christensen maintained a private practice in family medicine. From 1992 to 1996 she was also a television journalist.Christensen also entered Virgin Island politics. As a member of the Democratic Party of the Virgin Islands, she has served as Democratic National Committeewoman, member of the Democratic Territorial Committee and Delegate to all the Democratic Conventions in 1984, 1988 and 1992. Christensen was also elected to the Virgin Islands Board of Education in 1984 and served for two years. She served as a member of the Virgin Islands Status Commission from 1988 to 1992.In 1996 Christensen was elected as the non-voting delegate from the Virgin Islands in the United States Congress. Despite her non-voting status, she serves on various house committees including the Committee on Natural Resources, and the Committee on the Homeland Security Committee. She also chairs the Natural Resources Subcommittee on Insular Affairs.Delegate Christensen is a Member of the Congressional Black Caucus, the Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues; the Congressional Travel and Tourism Caucus; the Congressional Rural Caucus, the Friends of the Caribbean Caucus; the Coastal Caucus and the Congressional National Guard and Reserve Caucus.Christensen is also a member of the National Medical Association, the Virgin Islands Medical Society, the Caribbean Studies Association, the Caribbean Youth Organization and the Virgin Islands Medical Institute.She is the mother of two daughters, Rabiah Green-George and Karida Green. Congresswoman Christensen also gained two new daughters, Lisa and Esther, and two sons, Bryan and David, through her 1998 marriage to Chris Christensen. Research more about this great American Champion and shear it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

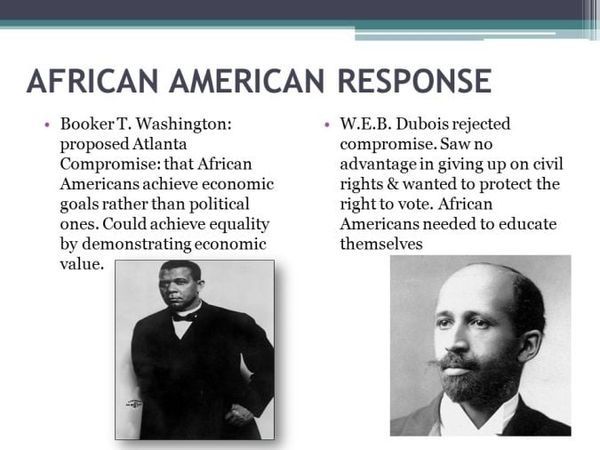

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was The Cotton States and International Exposition Speech was an address on the topic of race relations given by Booker T. Washington on September 18, 1895.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was The Cotton States and International Exposition Speech was an address on the topic of race relations given by Booker T. Washington on September 18, 1895. The speech laid the foundation for the Atlanta compromise, an agreement between African-American leaders and Southern white leaders in which Southern blacks would work meekly and submit to white political rule, while Southern whites guaranteed that blacks would receive basic education and due process of law.The speech, presented before a predominantly white audience at the Cotton States and International Exposition (the site of today’s Piedmont Park) in Atlanta, Georgia, has been recognized as one of the most important and influential speeches in American history. The speech was preceded by the reading of a dedicatory ode written by Frank Lebby Stanton. Washington began with a call to the blacks, who composed one third of the Southern population, to join the world of work. He declared that the South was where blacks were given their chance, as opposed to the North, especially in the worlds of commerce and industry. He told the white audience that rather than relying on the immigrant population arriving at the rate of a million people a year, they should hire some of the nation’s eight million blacks. He praised blacks’ loyalty, fidelity and love in service to the white population, but warned that they could be a great burden on society if oppression continued, stating that the progress of the South was inherently tied to the treatment of blacks and protection of their liberties.He addressed the inequality between commercial legality and social acceptance, proclaiming that “The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera house.” Washington also promoted segregation by claiming that blacks and whites could exist as separate fingers of a hand.The title “Atlanta Compromise” was given to the speech by W. E. B. Du Bois, who believed it was insufficiently committed to the pursuit of social and political equality for blacks.Although the speech was not recorded at its initial presentation in 1895, Washington recorded a portion of the speech during a trip to New York in 1908. This recording has been included in the United States National Recording Registry. Today in our History – September 18, 1895 – Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois debate in Atlanta, Georgia.Atlanta Compromise, classic statement on race relations articulated by Booker T. Washington, a leading Black educator in the United States in the late 19th century. In a speech at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia, on September 18, 1895, Washington asserted that vocational education, which gave African Americans an opportunity for economic security, was more valuable to them than social advantages, higher education, or political office.In one sentence he summarized his concept of race relations appropriate for the times: “In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” In return for African Americans’ remaining peaceful and socially separate from whites, the white community needed to accept responsibility for improving the social and economic conditions of all Americans, regardless of skin colour, Washington argued. This notion of shared responsibilities is what came to be known as the Atlanta Compromise. Washington closed his address by saying:Nothing in thirty years has given us more hope and encouragement and drawn us so near to you of the white race as these opportunity offered by this Exposition, and here bending, as it were, over the altar that represents the results of the struggles of your race and mine, both starting practically empty handed three decades ago, I pledge that in your effort to work out the great and intricate problem which God has laid at the doors of the South, you shall have at all times the patient, sympathetic help of my race….Far above and beyond material benefit, will be that higher good, that let us pray God will come, in a blotting out of sectional differences and racial animosities and suspicions, and in a determination even in the remotest corner, to administer absolute justice, in a willing obedience among all classes to the mandates of law. This, this, coupled with our material prosperity, will bring into our beloved South new Heaven and new Earth.White leaders in both the North and the South greeted Washington’s speech with enthusiasm, but it disturbed Black intellectuals who feared that Washington’s “accommodations” philosophy would doom Blacks to indefinite subservience to whites.This criticism of the Atlanta Compromise was best articulated by W.E.B. Du Bois in The Souls of Black Folk (1903): “Mr. Washington represents in Negro thought the old attitude of adjustment and submission.…[His] programmer practically accepts the alleged inferiority of the Negro races.” Advocating full civil rights as an alternative to Washington’s policy of accommodation, Du Bois organized a faction of Black leaders into the Niagara Movement (1905), which led to the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (1909). Research more about this historic event and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

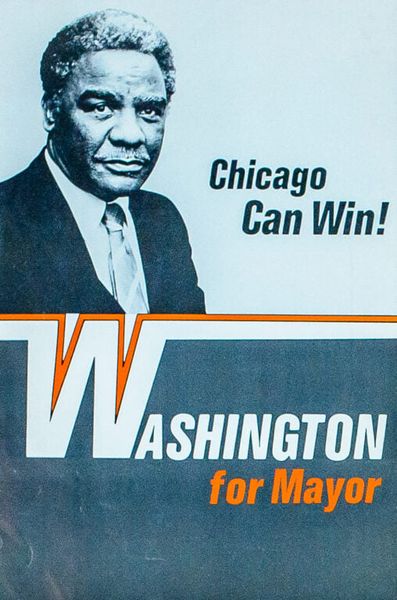

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American lawyer and politician who was the 51st Mayor of Chicago.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American lawyer and politician who was the 51st Mayor of Chicago. He became the first African American to be elected as the city’s mayor in April 1983 after a multiracial coalition of progressives supported his election. He served as mayor from April 29, 1983 until his death on November 25, 1987. Born in Chicago and raised in the Bronzeville neighborhood, he became involved in local 3rd Ward politics under Chicago Alderman and future Congressman Ralph Metcalfe after graduating from Roosevelt University and Northwestern University School of Law.He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1981 to 1983, representing Illinois’s first district. He had previously served in the Illinois State Senate and the Illinois House of Representatives from 1965 until 1976.A lot of folks who submit questions to Curious City take the call quite literally: What do you want to know about Chicago, the region or the people who live there? Questioner Jon Quinn put his own twist by submitting our first (and only) question about a robot — not just any robot, but the talking, animatronic likeness of former mayor Harold Washington that sits in a corner of the DuSable Museum of African American History.The team spent four years cycling through options, dispensing with staid life-sized statues made of bronze or others covered in resin. Eventually, someone mentioned that animatronic technology was dropping in price, with costs ranging between $10,000 and $30,000, depending on how large a figure’s range of movement needs to be.“It was like, we could literally put him at his desk, we could literally bring video and audio into the presentation to make it that much more interactive,” Bethea says. “That’s where the excitement came because it was like, ‘What? We can actually get this!’”Today in our History – September 17, 1991 –The DuSable Museum honors former Mayor Harold Washington.Harold Lee Washington (April 15, 1922 – November 25, 1987) Translating Harold the man into Harold the robotThe DuSable team hired Life Formations, an Ohio-based factory of the life-like that’s created everything from Abe Lincoln to a drum-playing gorilla. Bethea says the most expensive (and difficult) part of the partnership was the “human sculpting,” or coming up with a just-right Harold. Bethea gathered photos, interviews, and even an iconic Playboy magazine profile article to help Life Formations recreate Washington’s likeness.Harold Washington posing in Playboy Magazine, which is one image Life Formations used to replicate the former mayor.Translating that material fell to a team that included designer and project manager Travis Gillum.“They gave us quite a bit of video footage that we tried to work from,” Gillum says, adding that Washington smiled quite a bit. “If [an animatronic has] to speak sternly as part of their character in final form, that becomes a little bit weird if they have a smile on their face.” Gillum says historic figures such as Washington and Abraham Lincoln typically require special care.“That’s a tough line to walk, especially with the humans,” he says. “Obviously if you’re not very realistic with the human, it can be somewhat disappointing and sometimes creepy. But at the same token, if it’s ultra-realistic, that can be really creepy to people.”Gillum’s nodding to the concept of the uncanny valley, coined in the 1970s by robotics professor Masahiro Mori. Even with that idea firmly in mind, Life Formations aimed to make Washington look realistic.Bethea invited Washington’s family to review the robot’s development. Bethea says there was some back-and-forth, mostly around big-ticket items. For instance, some family members felt the early bust of Harold’s head (still pigmentless and hairless at that point) actually looked like “their Harold,” but the museum gave the robot several hairdos because the curl pattern wasn’t quite right and the grays weren’t scattered accurately.Another consideration: Washington died at age 65, but which time in Harold’s life should the robot depict? Washington’s hair greyed as he served as mayor, but he had also gained dozens of pounds during his terms. The family felt that the final body of the ‘bot was too slim. Washington had weighed 284 lbs at his death, but Bethea says he took “artistic license” by representing a healthier Washington that looked closer to age 58.At the touch of a button, the Harold Washington robot gives three presentations, one each about Washington’s mayoral campaign, his struggle to push a legislative agenda during Chicago’s Council Wars, and his funeral and legacy. (A kicker: He invites patrons to check out Chicago’s population of green parrots — a fixture of the South Side’s Washington Park.)Did they get it right?Bethea’s a fan of the DuSable Museum’s Harold Washington likeness (he calls it “his baby”), but not everyone is sold on how the robot turned out. Jacky Grimshaw, Vice President of Policy at the Center for Neighborhood Technology, and one of Washington’s former advisors, says the Harold ‘bot is okay for people who didn’t know him, but it doesn’t dig below the surface.“For me, it doesn’t really get at who Harold was,” she says.A young Grimshaw first knew Washington from Corpus Christi Church, where she saw the future mayor hobnob with Chicago aldermen and other politicians. While she was graduating college, Grimshaw’s mother was involved in Washington’s campaign for Illinois senator.It wasn’t long before her mother set her up with a gig as a staffer. Later, she served in Washington’s own mayoral administration, where she formed housing policy.Grimshaw believes DuSable visitors don’t sense Harold Washington as a person; it’s not that a patron should know Washington preferred eggs or oatmeal for breakfast, but to understand him, she says, they need a heftier dose of his personality. He moved people, she says. Seeing him in action was like a 1983 edition of Obama’s “Yes We Can” campaign.“He was such a magnetic person that you would know he was there,” she says, adding that that was the case in small venues or in rooms of more than a hundred.“That exhibit doesn’t even begin to relay that kind of personality, that kind of magnetism, that interaction with people which I believe … was nourishing to him.”For museum curator Bethea, the proof of the robot’s effectiveness is its impact.“You gravitate towards it and it pulls you in, then you really start to think about that person’s life; legacy and where they fit history and how hopefully you relate,” he says.Interestingly, that’s exactly what happened for Jon Quinn, our questioner. After his encounter with the robot, he spent two months diving deep into Harold, his history and his legacy: He sought out This American Life’s two part special on Washington’s read the biography Fire on the Prairie, and he closely watched Chuy Garcia’s 2015 mayoral campaign.Garcia campaigned for Washington and considered him a mentor. Garcia lost the 2015 race for mayor to incumbent Rahm Emanuel.Quinn even thinks it should be a requirement that Chicagoans venture to the DuSable Museum.“As strange and odd as that [animatronic] was, it was a really important afternoon for me in this weird way because it got me thinking a lot about this person and his legacy and what things from his mayoralty are still with us,” he says. “It went from this moment of eerie, uncanny valley creepiness to this fascinating exploration of the city’s recent history and politics.” Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!