GM – FBF –

Today , I would like to share with you, a black female who was one of the most

influential jazz singers of all time. She had a thriving career for many years

before she lost her battle with addiction. She is considered one of best Enjoy!

Remember – “In this country,

don’t forget, a habit is no damn private hell. There’s no solitary confinement

outside of jail. A habit is hell for those you love. And in this country it’s

the worst kind of hell for those who love you.” – Billie Holiday

Today in our Hsitory – July 17,

1915 – Actress, singer, and Jass person, Billie Holiday was born.

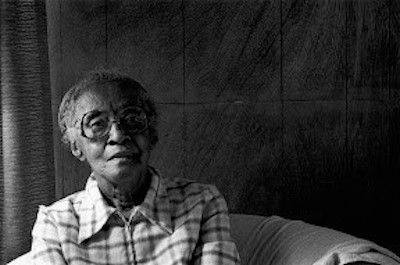

Jazz vocalist Billie Holiday was

born in 1915 in Philadelphia. Considered one of the best jazz vocalists of all

time, Holiday had a thriving career as a jazz singer for many years before she

lost her battle with substance abuse.

Also known as Lady Day, her

autobiography was made into the 1972 film Lady Sings the Blues. In 2000, Billie

Holiday was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Billie Holiday was born Eleanora

Fagan on April 7, 1915, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Some sources say her

birthplace was Baltimore, Maryland, and her birth certificate reportedly reads

“Elinore Harris.”)

Holiday spent much of her

childhood in Baltimore. Her mother, Sadie, was only a teenager when she had

her. Her father is widely believed to be Clarence Holiday, who eventually

became a successful jazz musician, playing with the likes of Fletcher

Henderson.

Unfortunately for Billie, her

father was an infrequent visitor in her life growing up. Sadie married Philip

Gough in 1920 and for a few years Billie had a somewhat stable home life. But

that marriage ended a few years later, leaving Billie and Sadie to struggle

along on their own again. Sometimes Billie was left in the care of other

people.

Holiday started skipping school,

and she and her mother went to court over Holiday’s truancy. She was then sent

to the House of Good Shepherd, a facility for troubled African American girls,

in January 1925.

Only 9 years old at the time, Holiday

was one of the youngest girls there. She was returned to her mother’s care in

August of that year. According to Donald Clarke’s biography, Billie Holiday:

Wishing on the Moon, she returned there in 1926 after she had been sexually

assaulted.

In her difficult early life,

Holiday found solace in music, singing along to the records of Bessie Smith and

Louis Armstrong. She followed her mother, who had moved to New York City in the

late 1920s, and worked in a house of prostitution in Harlem for a time.

Around 1930, Holiday began

singing in local clubs and renamed herself “Billie” after the film

star Billie Dove.

At the age of 18, Holiday was discovered by producer John Hammond while she was

performing in a Harlem jazz club. Hammond was instrumental in getting Holiday

recording work with an up-and-coming clarinetist and bandleader Benny Goodman.

With Goodman, she sang vocals for

several tracks, including her first commercial release “Your Mother’s

Son-In-Law” and the 1934 top ten hit “Riffin’ the Scotch.”

Known for her distinctive

phrasing and expressive, sometimes melancholy voice, Holiday went on to record

with jazz pianist Teddy Wilson and others in 1935.

She made several singles,

including “What a Little Moonlight Can Do” and “Miss Brown to

You.” That same year, Holiday appeared with Duke Ellington in the film

Symphony in Black.

Around this time, Holiday met and befriended saxophonist Lester Young, who was

part of Count Basie’s orchestra on and off for years. He even lived with

Holiday and her mother Sadie for a while.

Young gave Holiday the nickname

“Lady Day” in 1937—the same year she joined Basie’s band. In return,

she called him “Prez,” which was her way of saying that she thought

it was the greatest.

Holiday toured with the Count

Basie Orchestra in 1937. The following year, she worked withArtie Shaw and his

orchestra. Holiday broke new ground with Shaw, becoming one of the first female

African American vocalists to work with a white orchestra.

Promoters, however, objected to

Holiday—for her race and for her unique vocal style—and she ended up leaving

the orchestra out of frustration.

Striking out on her own, Holiday

performed at New York’s Café Society. She developed some of her trademark stage

persona there—wearing gardenias in her hair and singing with her head tilted

back.

During this engagement, Holiday

also debuted two of her most famous songs, “God Bless the Child” and

“Strange Fruit.” Columbia, her record company at the time, was not

interested in “Strange Fruit,” which was a powerful story about the

lynching of African Americans in the South.

Holiday recorded the song with

the Commodore label instead. “Strange Fruit” is considered to be one

of her signature ballads, and the controversy that surrounded it—some radio

stations banned the record—helped make it a hit.

Over the years, Holiday sang many

songs of stormy relationships, including “T’ain’t Nobody’s Business If I

Do” and “My Man.” These songs reflected her personal romances,

which were often destructive and abusive.

Holiday married James Monroe in

1941. Already known to drink, Holiday picked up her new husband’s habit of

smoking opium. The marriage didn’t last—they later divorced—but Holiday’s

problems with substance abuse continued.

That same year, Holiday had a hit

with “God Bless the Child.” She later signed with Decca Records in

1944 and scored an R&B hit the next year with “Lover Man.”

Her boyfriend at the time was

trumpeter Joe Guy, and with him she started using heroin. After the death of

her mother in October 1945, Holiday began drinking more heavily and escalated

her drug use to ease her grief.

Despite her personal problems,

Holiday remained a major star in the jazz world—and even in popular music as

well. She appeared with her idol Louis Armstrong in the 1947 film New Orleans,

albeit playing the role of a maid.

Unfortunately, Holiday’s drug use

caused her a great professional setback that same year. She was arrested and

convicted for narcotics possession in 1947. Sentenced to one year and a day of

jail time, Holiday went to a federal rehabilitation facility in Alderston, West

Virginia.

Released the following year,

Holiday faced new challenges. Because of her conviction, she was unable to get

the necessary license to play in cabarets and clubs. Holiday, however, could

still perform at concert halls and had a sold-out show at the Carnegie Hall not

long after her release.

With some help from John Levy, a

New York club owner, Holiday was later to get to play in New York’s Club Ebony.

Levy became her boyfriend and manager by the end of the 1940s, joining the

ranks of the men who took advantage of Holiday.

Also around this time, she was

again arrested for narcotics, but she was acquitted of the charges.

While her hard living was taking a toll on her voice, Holiday continued to tour

and record in the 1950s. She began recording for Norman Granz, the owner of

several small jazz labels, in 1952. Two years later, Holiday had a hugely

successful tour of Europe.

Holiday also caught the public’s

attention by sharing her life story with the world in 1956. Her autobiography,

Lady Sings the Blues (1956), was written in collaboration by William

Dufty.

Some of the material in the book, however, must be taken with a grain of salt.

Holiday was in rough shape when she worked with Dufty on the project, and she claimed

to have never read the book after it was finished.

Around this time, Holiday became

involved with Louis McKay. The two were arrested for narcotics in 1956, and

they married in Mexico the following year. Like many other men in her life,

McKay used Holiday’s name and money to advance himself.

Despite all of the trouble she had been experiencing with her voice, she

managed to give an impressive performance on the CBS television broadcast The

Sound of Jazz with Ben Webster, Lester Young, and Coleman Hawkins.

After years of lackluster

recordings and record sales, Holiday recorded Lady in Satin (1958) with the Ray

Ellis Orchestra for Columbia. The album’s songs showcased her rougher sounding

voice, which still could convey great emotional intensity.

Holiday gave her final

performance in New York City on May 25, 1959. Not long after this event,

Holiday was admitted to the hospital for heart and liver problems.

She was so addicted to heroin that she was even arrested for possession while

in the hospital. On July 17, 1959, Holiday died from alcohol- and drug-related

complications.

More than 3,000 people turned out

to say good-bye to Lady Day at her funeral held in St. Paul the Apostle Roman

Catholic Church on July 21, 1959. A who’s who of the jazz world attended the

solemn occasion, including Benny Goodman, Gene Krupa, Tony Scott, Buddy Rogers

and John Hammond.

Considered one of the best jazz vocalists of all time, Holiday has been an

influence on many other performers who have followed in her footsteps.

Her autobiography

was made into the 1972 film Lady Sings the Blues with famed singer Diana Ross

playing the part of Holiday, which helped renew interest in Holiday’s

recordings.

In 2000, Billie Holiday was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with

Diana Ross handling the honors. Research more about Black singers in American

and share with you babies. Make it a champion Day!