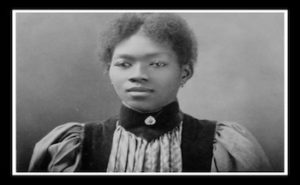

GM – FBF – Today, I would like to remind you of a great American poet and writer. She also taught on the University level and she was sued in court by the wife of Richard Wright and she sued Alex Haley in court. If you never heard of her or if you fogotten this is a great read. Enjoy!

Remember – “When I was about eight, I decided that the most wonderful thing, next to a human being, was a book.” – Margaret Walker

Today in our History – July 7,1915 –

Margaret Walker (Margaret Abigail Walker Alexander by marriage; July 7, 1915 – November 30, 1998) was an American poet and writer. She was part of the African-American literary movement in Chicago, known as the Chicago Black Renaissance. Her notable works include the award-winning poem For My People (1942) and the novel Jubilee (1966), set in the South during the American Civil War.

Walker was born in Texas, Alabama, to Sigismund C. Walker, a minister, and Marion (née Dozier) Walker, who helped their daughter by teaching her philosophy and poetry as a child. Her family moved to New Orleans when Walker was a young girl. She attended school there, including several years of college, before she moved north to Chicago.

In 1935, Walker received her Bachelor of Arts Degree from Northwestern University. In 1936 she began work with the Federal Writers’ Project under the Works Progress Administration of the President Franklin D. Roosevelt administration during the Great Depression. She was a member of the South Side Writers Group, which included authors such as Richard Wright, Arna Bontemps, Fenton Johnson, Theodore Ward, and Frank Marshall Davis.

In 1942, she received her master’s degree in creative writing from the University of Iowa. In 1965, she returned to that school to earn her Ph.D.

Walker married Firnist Alexander in 1943 and moved to Mississippi to be with him. They had four children together and lived in the capital of Jackson.

Walker became a literature professor at what is today Jackson State University, a historically black college, where she taught from 1949 to 1979. In 1968, Walker founded the Institute for the Study of History, Life, and Culture of Black People (now the Margaret Walker Center) and her personal papers are now stored there. In 1976, she went on to serve as the Institute’s director.

In 1942, Walker’s poetry collection For My People won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Competition under the judgeship of editor Stephen Vincent Benet, thus making her the first black woman to receive a national writing prize. Her For My People was considered the “most important collection of poetry written by a participant in the Black Chicago Renaissance before Gwendolyn Brooks’s A Street in Bronzeville.” Richard Barksdale says: “The [title] poem was written when “world-wide pain, sorrow, and affliction were tangibly evident, and few could isolate the Black man’s dilemma from humanity’s dilemma during the depression years or during the war years.” He said that the power of resilience presented in the poem is a hope Walker holds out not only to black people, but to all people, to “all the Adams and Eves.”

Walker’s second published book (and only novel), Jubilee (1966), is the story of a slave family during and after the Civil War, and is based on her great-grandmother’s life. It took her thirty years to write. Roger Whitlow says: “It serves especially well as a response to white ‘nostalgia’ fiction about the antebellum and Reconstruction South.”

This book is considered important in African-American literature and Walker is an influential figure for younger authors. She was the first of a generation of women who started publishing more novels in the 1970s.

In 1975, Walker released three albums of poetry on Folkways Records – Margaret Walker Alexander Reads Poems of Paul Laurence Dunbar and James Weldon Johnson and Langston Hughes; Margaret Walker Reads Margaret Walker and Langston Hughes; and The Poetry of Margaret Walker.

Walker received a Candace Award from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women in 1989. In 1978, Margaret Walker sued Alex Haley, claiming that his 1976 novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family had violated Jubilee’s copyright by borrowing from her novel. The case was dismissed.

In 1991 Walker was sued by Ellen Wright, the widow of Richard Wright, on the grounds that Walker’s use of unpublished letters and an unpublished journal in a just-published biography of Wright violated the widow’s copyright. Wright v. Warner Books was dismissed by the district court, and this judgment was supported by the appeals court.

Walker died of breast cancer in Chicago, Illinois, in 1998, aged 83. Walker was inducted into The Chicago Literary Hall of Fame in 2014. Research more about this great American poet and writer. Please share with your babies and make it a champion day!