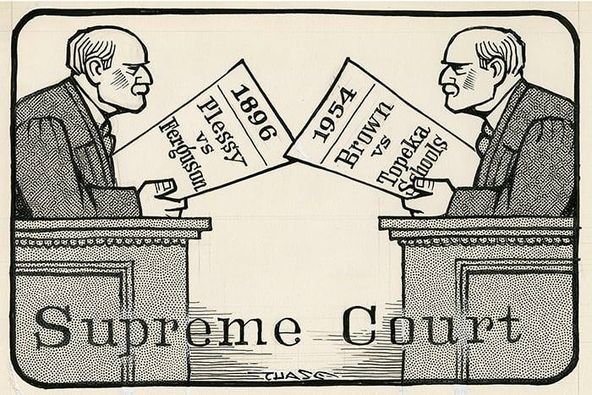

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion event was Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Supreme Court considered the constitutionality of a Louisiana law passed in 1890 “providing for separate railway carriages for the white and colored races.” The law, which required that all passenger railways provide separate cars for blacks and whites, stipulated that the cars be equal in facilities, banned whites from sitting in black cars and blacks in white cars (with exception to “nurses attending children of the other race”), and penalized passengers or railway employees for violating its terms.Today in our History May 18, 1896 – The U.S, Supreme Court rules against Plessy.Homer Plessy, the plaintiff in the case, was seven-eighths white and one-eighth black, and had the appearance of a white man. On June 7, 1892, he purchased a first-class ticket for a trip between New Orleans and Covington, La., and took possession of a vacant seat in a white-only car. Duly arrested and imprisoned, Plessy was brought to trial in a New Orleans court and convicted of violating the 1890 law. He then filed a petition against the judge in that trial, Hon. John H. Ferguson, at the Louisiana Supreme Court, arguing that the segregation law violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which forbids states from denying “to any person within their jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws,” as well as the Thirteenth Amendment, which banned slavery.The Court ruled that, while the object of the Fourteenth Amendment was to create “absolute equality of the two races before the law,” such equality extended only so far as political and civil rights (e.g., voting and serving on juries), not “social rights” (e.g., sitting in a railway car one chooses). As Justice Henry Brown’s opinion put it, “if one race be inferior to the other socially, the constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane.” Furthermore, the Court held that the Thirteenth Amendment applied only to the imposition of slavery itself.The Court expressly rejected Plessy’s arguments that the law stigmatized blacks “with a badge of inferiority,” pointing out that both blacks and whites were given equal facilities under the law and were equally punished for violating the law. “We consider the underlying fallacy of [Plessy’s] argument” contended the Court, “to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it.”Justice John Marshall Harlan entered a powerful — and lone — dissent, noting that “in view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.”Until the mid-twentieth century, Plessy v. Ferguson gave a “constitutional nod” to racial segregation in public places, foreclosing legal challenges against increasingly-segregated institutions throughout the South. The railcars in Plessy notwithstanding, the black facilities in these institutions were decidedly inferior to white ones, creating a kind of racial caste society. However, in the landmark decision Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the “separate but equal” doctrine was abruptly overturned when a unanimous Supreme Court ruled that segregating children by race in public schools was “inherently unequal” and violated the Fourteenth Amendment. Brown provided a major catalyst for the civil rights movement (1955-68), which won social, not just political and civil, racial equality before the law. After four decades, Justice Harlan’s dissent became the law of the land. Following Brown, the Supreme Court has consistently ruled racial segregation in public settings to be unconstitutional. Research more about this great American Court decision and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

Tag: Brandon hardison

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was not just an influential and notable novelist, poet, and songwriter,

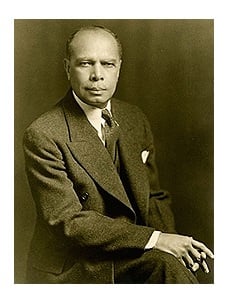

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was not just an influential and notable novelist, poet, and songwriter, He was a lawyer, a United States consul in a foreign nation, and served an important role in combating racism through his position in the NAACP.Today in our History – May 17, James Weldon Johnson wrights “Lift every Voice and sing”.Johnson was born in 1871 in Jacksonville, Florida, the son of Helen Louise Dillet, a native of Nassau, Bahamas, and James Johnson. His maternal great-grandmother, Hester Argo, had escaped from Saint-Domingue (today Haiti) during the revolutionary upheaval in 1802, along with her three young children, including James’ grandfather Stephen Dillet (1797–1880). Although originally headed to Cuba, their boat was intercepted by privateers and they were taken to Nassau, where they permanently settled. In 1833 Stephen Dillet became the first man of color to win election to the Bahamian legislature (ref: James Weldon Johnson, Along This Way, his autobiography).James’ brother was John Rosamond Johnson, who became a composer. The boys were first educated by their mother, a musician and a public school teacher, before attending Edwin M. Stanton School. Their mother imparted to them her great love and knowledge of English literature and the European tradition in music. At the age of 16, Johnson enrolled at Atlanta University, a historically black college, from which he graduated in 1894. In addition to his studies for the bachelor’s degree, he also completed some graduate coursework.The achievement of his father, a preacher, and the headwaiter at the St. James Hotel, a luxury establishment built when Jacksonville was one of Florida’s first winter resort destinations, inspired young James to pursue a professional career. Molded by the classical education for which Atlanta University was best known, Johnson regarded his academic training as a trust. He knew he was expected to devote himself to helping black people advance. Johnson was a prominent member of Phi Beta Sigma fraternity.Johnson and his brother Rosamond moved to New York City as young men, joining the Great Migration out of the South in the first half of the 20th century. They collaborated on songwriting and achieved some success on Broadway in the early 1900s.Over the next 40 years Johnson served in several public capacities, working in education, the diplomatic corps, and civil rights activism. In 1904 he participated in Theodore Roosevelt’s successful presidential campaign. After becoming president, Roosevelt appointed Johnson as United States consul at Puerto Cabello, Venezuela from 1906 to 1908, and to Nicaragua from 1909 to 1913.In 1910, Johnson married Grace Nail, whom he had met in New York City several years earlier while working as a songwriter. A cultured and well-educated New Yorker, Grace Nail Johnson later collaborated with her husband on a screenwriting project.After their return to New York from Nicaragua, Johnson became increasingly involved in the Harlem Renaissance, a great flourishing of art and writing. He wrote his own poetry and supported work by others, also compiling and publishing anthologies of spirituals and poetry. Owing to his influence and his innovative poetry, Johnson became a leading voice in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s.He became involved in civil rights activism, especially the campaign to pass the federal Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, as Southern states did not prosecute perpetrators. He was a speaker at the 1919 National Conference on Lynching. as a field secretary for the NAACP in 1917, Johnson rose to become one of the most successful officials in the organization. He traveled to Memphis, Tennessee, for example, to investigate a brutal lynching that was witnessed by thousands. His report on the carnival-like atmosphere surrounding the burning-to-death of Ell Persons was published nationally as a supplement to the July 1917 issue of the NAACP’s Crisis magazine, and during his visit there he chartered the Memphis chapter of the NAACP. His 1920 report about “the economic corruption, forced labor, press censorship, racial segregation, and wanton violence introduced to Haiti by the US occupation encouraged numerous African Americans to flood the State Department and the offices of Republican Party officials with letters” calling for an end to the abuses and to remove troops. The US finally ended its occupation in 1934, long after the threat of Germany in the area had been ended by its defeat in the First World War.Appointed in 1920 as the first executive secretary of the NAACP, Johnson helped increase membership and extended the movement’s reach by organizing numerous new chapters in the South.During this period the NAACP was mounting frequent legal challenges to the southern states’ disenfranchisement of African Americans, which had been established at the turn of the century by such legal devices as poll taxes, literacy tests, and white primaries.Johnson died in 1938 while vacationing in Wiscasset, Maine, when the car his wife was driving was hit by a train. His funeral in Harlem was attended by more than 2000 people. Johnson’s ashes are interred at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.In the summer of 1891, following his freshman year at Atlanta University, Johnson went to a rural district in Georgia to teach the descendants of former slaves. “In all of my experience there has been no period so brief that has meant so much in my education for life as the three months I spent in the backwoods of Georgia,” Johnson wrote. “I was thrown for the first time on my own resources and abilities.” Johnson graduated from Atlanta University in 1894.After graduation, he returned to Jacksonville, where he taught at Stanton, a school for African-American students (the public schools were segregated) that was the largest of all the schools in the city. In 1906, at the young age of 35, he was promoted to principal. In the segregated system, Johnson was paid less than half of what white colleagues earned. He improved black education by adding the ninth and tenth grades to the school, to extend the years of schooling. He later resigned from this job to pursue other goals.While working as a teacher, Johnson also read the law to prepare for the bar. In 1897, he was the first African American admitted to the Florida Bar Exam since the Reconstruction era ended. He was also the first black in Duval County to seek admission to the state bar. In order to be accepted, Johnson had a two-hour oral examination before three attorneys and a judge. He later recalled that one of the examiners, not wanting to see a black man admitted, left the room. Johnson drew on his law background especially during his years as a civil rights activist and leading the NAACP.In 1930 at the age of 59, Johnson returned to education after his many years leading the NAACP. He accepted the Spence Chair of Creative Literature at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. The university created the position for him, in recognition of his achievements as a poet, editor, and critic during the Harlem Renaissance. In addition to discussing literature, he lectured on a wide range of issues related to the lives and civil rights of black Americans. He held this position until his death. In 1934 he also was appointed as the first African-American professor at New York University, where he taught several classes in literature and culture. As noted above, in 1901 Johnson had moved to New York City with his brother J. Rosamond Johnson to work in musical theater. They collaborated on such hits as “Tell Me, Dusky Maiden”, “Nobody’s Looking but the Owl and the Moon,” and the spiritual Dem Bones, for which Johnson wrote the lyrics and his brother the music. Johnson composed the lyrics of “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” to honor renowned educator Booker T. Washington who was visiting Stanton School, when the poem was recited by 500 school children as a tribute to Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. This song became widely popular and has become known as the “Negro National Anthem,” a title that the NAACP adopted and promoted. The song included the following lines:Lift every voice and sing, till earth and Heaven ring,Ring with the harmonies of liberty;Let our rejoicing rise, high as the listening skies,Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.Sing a song full of faith that the dark past has taught us,Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us;Facing the rising sun of our new day begun,Let us march on till victory is won.”Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” had influenced other artistic works, inspiring art such as Gwendolyn Ann Magee’s quilted mosaics. “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” contrasted with W.E.B. Du Bois’ exploration in Souls of Black Folk of the fears of post-emancipation generations of African Americans.After some successes, the brothers worked on Broadway and collaborated with producer and director Bob Cole. Johnson also collaborated on the opera Tolosa with his brother, who wrote the music; it satirized the U.S. annexation of the Pacific islands. Thanks to his success as a Broadway songwriter, Johnson moved in the upper echelons of African-American society in Manhattan and Brooklyn.In 1906 Johnson was appointed by the Roosevelt Administration as consul of Puerto Cabello, Venezuela. In 1909, he transferred to Corinto, Nicaragua. During his stay at Corinto, a rebellion erupted against President Adolfo Diaz. Johnson proved an effective diplomat in such times of strain.His positions also provided time and stimulation to pursue his literary career. He wrote substantial portions of his novel, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, and his poetry collection, Fifty Years, during this period. His poetry was published in major journals such as The Century Magazine and in The Independent.Johnson’s first success as a writer was the poem “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” (1899), which his brother Rosamond set to music; the song became unofficially known as the “Negro National Anthem.” During his time in the diplomatic service, Johnson completed what became his most well-known book, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, which he published anonymously in 1912. He chose anonymity to avoid any controversy that might endanger his diplomatic career. It was not until 1927 that Johnson acknowledged writing the novel, stressing that it was not a work of autobiography but mostly fictional.In this period, he also published his first poetry collection, Fifty Years and Other Poems (1917). It showed his increasing politicization and adoption of the black vernacular influences that characterize his later work.Johnson returned to New York, where he was involved in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. He had a broad appreciation for black artists, musicians and writers, and worked to heighten awareness in the wider society of their creativity.In 1922, he published a landmark anthology The Book of American Negro Poetry, with a “Preface” that celebrated the power of black expressive culture. He compiled and edited the anthology The Book of American Negro Spirituals, which was published in 1925.He continued to publish his own poetry as well. Johnson’s collection God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (1927) is considered most important. He demonstrated that black folk life could be the material of serious poetry. He also comments on the violence of racism in poems such as “Fragment,” which portrays slavery as against both God’s love and God’s law.Following the flourishing of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s, Johnson reissued his anthology of poetry by black writers, The Book of American Negro Poetry, in 1931, including many new poets. This established the African-American poetic tradition for a much wider audience and also inspired younger poets.In 1930, he published a sociological study, Black Manhattan (1930). His Negro Americans, What Now? (1934) was a book-length address advocating fuller civil rights for African Americans. By this time, tens of thousands of African Americans had left the South for northern and midwestern cities in the Great Migration, but the majority still lived in the South. There they were politically disenfranchised and subject to Jim Crow laws and white supremacy. Outside the South, many faced discrimination but had more political rights and chances for education and work.At least one of Mr. Johnson’s works was credited as leading to a movie. “Go Down, Death!” was a Harlemwood Studios production, directed by Spencer Williams. In the film credits, it states, “Alfred N. Sack Reverently Presents….” (the film), with hymns playing in the background. The film opens:“Forward: This Story of Love and Simple Faith and Triumph of Good Over Evil was inspired by the Poem “GO DOWN, DEATH!” from the Pen of the Celebrated Negro Author James Weldon Johnson, Now of Sainted Memory.”The film (recently shown on Turner Classic Movies (January 4, 2020) as a filler piece) featured an all African-American cast, including Myra D. Hemings, Samuel H. James, and Eddie L. Houston, Spencer Williams, and Amos Droughan, among others. It also included a dancing and band sequence, depicting a fun looking, middle class oriented club with drinks and gambling, as its opening backdrop.While attending Atlanta University, Johnson became known as an influential campus speaker. In 1892 he won the Quiz Club Contest in English Composition and Oratory. He founded and edited the Daily American newspaper in 1895. At a time when southern legislatures were passing laws and constitutions that disenfranchised blacks and Jim Crow laws to impose racial segregation, the newspaper covered both political and racial topics. It was terminated a year later due to financial difficulty. These early endeavors were the start of Johnson’s long period of activism.In 1904 he accepted a position as the treasurer of the Colored Republican Club, started by Charles W. Anderson. A year later he was elected as president of the club. He organized political rallies. During 1914 Johnson became editor of the editorial page of the New York Age, an influential African-American weekly newspaper based in New York City. In the early 20th century, it had supported Booker T. Washington’s position for racial advancement by industrious work within the racial community, against the arguments of W. E. B. Du Bois for development of a “talented tenth” and political activism to challenge white supremacy. Johnson’s writing for the Age displayed the political gift that soon made him famous.In 1916, Johnson started working as a field secretary and organizer for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which had been founded in 1910. In this role, he built and revived local chapters. Opposing race riots in northern cities and the lynchings frequent in the South during and immediately after the end of World War I, Johnson engaged the NAACP in mass demonstrations. He organized a silent protest parade of more than 10,000 African Americans down New York City’s Fifth Avenue on July 28, 1917 to protest the still-frequent lynchings of blacks in the South.Social tensions erupted after veterans returned from the First World War, and tried to find work. In 1919, Johnson coined the term “Red Summer” and organized peaceful protests against the white racial violence against blacks that broke out that year in numerous industrial cities of the North and Midwest. There was fierce competition for housing and jobs.Johnson traveled to Haiti to investigate conditions on the island, which had been occupied by U.S. Marines since 1915, ostensibly because of political unrest. As a result of this trip, Johnson published a series of articles in The Nation in 1920 in which he described the American occupation as brutal. He offered suggestions for the economic and social development of Haiti. These articles were later collected and reprinted as a book under the title Self-Determining Haiti.In 1920 Johnson was chosen as the first black executive secretary of the NAACP, effectively the operating officer position. He served in this role through 1930. He lobbied for the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill of 1921, which was passed easily by the House, but repeatedly defeated by the white Southern bloc in the Senate.Throughout the 1920s, Johnson supported and promoted the Harlem Renaissance, trying to help young black authors to get published. Shortly before his death in 1938, Johnson supported efforts by Ignatz Waghalter, a Polish-Jewish composer who had escaped the Nazis of Germany, to establish a classical orchestra of African-American musicians.Johnson was killed on June 26th, 1938, when the car he was riding in was hit by a train in Wiscasset, Maine. He was 67. His wife, the driver, survived with serious injuries. Research more about this great American Champion and shareit with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was called Uncle Tom, kissing up to the White man, not marrying into his race and even being a republican.

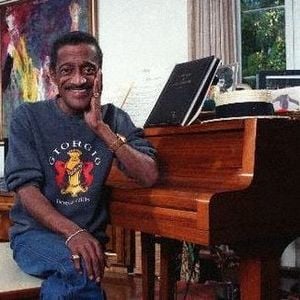

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was called Uncle Tom, kissing up to the White man, not marrying into his race and even being a republican. I will always remember him for the longevity, his passion for his craft and always finding ways to stay in the “Main Stream” of American entertainment. He was an American singer, dancer, actor, vaudevillian and comedian whom critic Randy Blaser called “the greatest entertainer ever to grace a stage in these United States.” At age three, he began his career in vaudeville with his father and the Will Mastin Trio, which toured nationally, and his film career began in 1933. After military service, he returned to the trio and became an overnight sensation following a nightclub performance at Ciro’s (in West Hollywood) after the 1951 Academy Awards. With the trio, he became a recording artist. In 1954, at the age of 29, he lost his left eye in a car accident. Several years later, he converted to Judaism, finding commonalities between the oppression experienced by African-American and Jewish communities. After a starring role on Broadway in Mr. Wonderful with Chita Rivera (1956), he returned to the stage in 1964 in a musical adaptation of Clifford Odets’ Golden Boy opposite Paula Wayne. He was nominated for a Tony Award for his performance and the show was said to have featured the first interracial kiss on Broadway. In 1960, He appeared in the Rat Pack film Ocean’s 11. In 1966, he had his own TV variety show, while his career slowed in the late 1960s, his biggest hit, “The Candy Man”, reached the top of the Billboard Hot 100 in June 1972, and he became a star in Las Vegas, earning him the nickname “Mister Show Business”.His popularity helped break the race barrier of the segregated entertainment industry. He did however have a complex relationship with the black community and drew criticism after publicly supporting President Richard Nixon in 1972.One day on a golf course with Jack Benny, he was asked what his handicap was. “Handicap?” he asked. “Talk about handicap. I’m a one-eyed Negro who’s Jewish.” This was to become a signature comment, recounted in his autobiography and in many articles. After reuniting with Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin in 1987, he toured with them and Liza Minnelli internationally, before his death in 1990. He died in debt to the Internal Revenue Service, and his estate was the subject of legal battles after the death of his wife.He was awarded the Spingarn Medal by the NAACP and was nominated for a Golden Globe Award and an Emmy Award for his television performances. He was a recipient of the Kennedy Center Honors in 1987, and in 2001, he was posthumously awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.Today in our History – May 16, 1990 Samuel George Davis Jr. (December 8, 1925 – May 16, 1990) died.Davis was an avid photographer who enjoyed shooting pictures of family and acquaintances. His body of work was detailed in a 2007 book by Burt Boyar titled Photo by Sammy Davis, Jr. “Jerry [Lewis] gave me my first important camera, my first 35 millimeter, during the Ciro’s period, early ’50s,” Boyar quotes Davis as saying. “And he hooked me.” Davis used a medium format camera later on to capture images. Boyar reports that Davis had said, “Nobody interrupts a man taking a picture to ask… ‘What’s that nigger doin’ here?'” His catalog includes rare photos of his father dancing onstage as part of the Will Mastin Trio and intimate snapshots of close friends Jerry Lewis, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, James Dean, Nat “King” Cole, and Marilyn Monroe. His political affiliations also were represented, in his images of Robert Kennedy, Jackie Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr. His most revealing work comes in photographs of wife May Britt and their three children,Tracey, Jeff and Mark.Davis was an enthusiastic shooter and gun owner. He participated in fast-draw competitions. Johnny Cash recalled that Davis was said to be capable of drawing and firing a Colt Single Action Army revolver in less than a quarter of a second. Davis was skilled at fast and fancy gunspinning and appeared on television variety shows showing off this skill. He also demonstrated gunspinning to Mark on The Rifleman in “Two Ounces of Tin.” He appeared in western films and as a guest star on several television westerns.Davis was a registered Democrat and supported John F. Kennedy’s 1960 election campaign as well as Robert F. Kennedy’s 1968 campaign. John F. Kennedy would later refuse to allow Davis to perform at his inauguration on account of his marriage with the white actress May Britt. Nancy Sinatra revealed in her 1986 book Frank Sinatra: My Father how Kennedy had planned to snub Davis as plans for his wedding to Britt were unfolding. He went on to become a close friend of President Richard Nixon (a Republican) and publicly endorsed him at the 1972 Republican National Convention. Davis also made a USO tour to South Vietnam at Nixon’s request.In February 1972, during the later stages of the Vietnam War, Davis went to Vietnam to observe military drug abuse rehabilitation programs and talk to and entertain the troops. He did this as a representative from President Nixon’s Special Action Office For Drug Abuse Prevention. He performed shows for up to 15,000 troops; after one two-hour performance he reportedly said, “I’ve never been so tired and felt so good in my life.” The U.S. Army made a documentary about Davis’s time in Vietnam performing for troops on behalf of Nixon’s drug treatment program. Nixon invited Davis and his wife, Altovise, to sleep in the White House in 1973, the first time African-Americans were invited to do so. The Davises spent the night in the Lincoln Bedroom. Davis later said he regretted supporting Nixon, accusing Nixon of making promises on civil rights that he did not keep. Davis was a longtime donor to the Reverend Jesse Jackson’s Operation PUSH organization and later supported Jackson’s 1984 campaign for President. In August 1989, Davis began to develop symptoms: a tickle in his throat and an inability to taste food. Doctors found a cancerous tumor in Davis’ throat.[43][80] He was a heavy smoker and had often smoked four packs of cigarettes a day as an adult. When told that surgery (laryngectomy) offered him the best chance of survival, Davis replied he would rather keep his voice than have a part of his throat removed; he was initially treated with a combination of chemotherapy and radiation. His larynx was later removed when his cancer recurred.He was released from the hospital on March 13, 1990. Davis died of complications from throat cancer two months later at his home in Beverly Hills, California, on May 16, 1990, at age 64. He was buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California. On May 18, 1990, two days after his death, the neon lights of the Las Vegas Strip were darkened for ten minutes as a tribute. Davis left the bulk of his estate, estimated at $4,000,000 to his widow, Altovise Davis, but he owed the IRS $5,200,000 which, after interest and penalties, had increased to over $7,000,000. His widow, Altovise Davis, became liable for his debt because she had co-signed his tax returns. She was forced to auction his personal possessions and real estate. Some of his friends in the industry, including Quincy Jones, Joey Bishop, Ed Asner, Jayne Meadows, and Steve Allen, participated in a fundraising concert at the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas.Altovise Davis and the IRS reached a settlement in 1997. After she died in 2009, their son Manny was named executor of the estate and majority-rights holder of his intellectual property. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is The Chip Woman’s Fortune is a 1923 one act play written by American playwright Willis Richardson.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is The Chip Woman’s Fortune is a 1923 one act play written by American playwright Willis Richardson. The play was produced by The Ethiopian Art Players and is historically important as the first serious work by an African American playwright to be presented on Broadway. Although Broadway had seen African American musical comedies and revues, it had never seen a serious drama.May 15, 1923 – The Chip Woman’s Fortune by Willis Richardson, the first dramatic work by an African American playwright to be mounted on Broadway, opens at the Frazee Theatre on BroadwayEmma: Liza’s daughter, 18 and beautifulLiza: Mother of Emma, struggling with her healthAunt Nancy: The “chip woman” who lives with Liza’s family in their homeSilas: Husband of LizaJim: Son of Aunt NancyThe play opens with Liza not feeling well and being taken care of by Aunt Nancy. Emma enters and is chastised for wearing makeup by Liza. Both Emma and Liza agree that Aunt Nancy has been a very helpful presence in the home, especially for Liza’s health. Liza explains to Emma that the Victrola has left the family in debt, and that Silas has been furloughed for a couple of days. With the family already being extremely poor, and men coming to gather the debt any minute, Liza suspects that Silas will need to put Aunt Nancy out of the house because she does not pay rent. Silas enters the home and explains how he suspects Aunt Nancy secretly has a fortune that she keeps buried in the backyard. He wants to either ask her for the money of kick her out. Aunt Nancy re-enters and confesses that she is keeping money in the backyard to save for her son who got out of jail that day and will be appearing at the house any minute. Jim enters, and gives Silas fifteen dollars. He then proceeds to take give half of the money that Aunt Nancy has saved for him to Silas. Silas repays his debts and Aunt Nancy and Jim exit.The Chip Woman’s Fortune is noted for its simplicity. None of the characters are over glorified or overdone. Bernard Peterson quotes from the New York Times review, “The Chip Woman’s Fortune…is an unaffected and wholly convincing transcript of everyday character. No one is tricked out of pleasure; no one is blackened to serve as a “dramatic” contrast.I am referring, of course, to points of essential character, not to that matter of walnut stain.” W.E.B DuBois wrote in The Crisis, “The Negro Drama in America took another step forward when The Ethiopian Art Players under Raymond O’Neil, came to Broadway, New York. Financially the experiment was a failure; but dramatically and spiritually it was one of the greatest successes this country as ever seen.”Noted as one of the most important playwrights for the African American community. In his essay, “The Hope of A Negro Drama,” Richardson stresses “that the plays written by African Americans should focus on the black community and not on racial tension and differences.” He goes on to state that most of his plays would be “drawn for the most part from folk tradition, they should center on black conflicts within the black community.” In his own words, as early as 1922, Richardson sent a letter to Gregory stating “Negro drama has been, next to my wife and children, the very hope of my life. I shall do all within my power to advance it.” During these formative years of black drama, Richardson exerted his energies towards promoting and perfecting his craft. Richardson was awarded the AUDELCO prize, which is a testament to his excellence in black theatre. Research more about this great American Champion artist and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was the first African-American president of the American Library Association, serving as its acting president from April 11 to July 22 in 1976 and then its president from July 22, 1976 to 1977.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was the first African-American president of the American Library Association, serving as its acting president from April 11 to July 22 in 1976 and then its president from July 22, 1976 to 1977. Also, in 1970 she became the first African American and the first woman to serve as director of a major library system in America, as director of the Detroit Public Library.Today in our History – May 14, 1913 – Clara Stanton Jones (May 14, 1913 – September 30, 2012) was born.Stanton Jones was born on May 14, 1913, in St. Louis, Missouri, to a close-knit, Catholic family. Her future career and impact in library science almost seemed predestined as she frequented the library at an early age. Jones recalls that she was one of the smallest patrons at the public library near her grandmother’s house; she was also among very few black children at that local library. Although Jones had very little interaction with librarians in her young years, she read what interested her and selected her own materials. Her mother, Etta J. Stanton, worked as a school teacher, lecturing at public school systems until her marriage. Due to the marriage bar prohibiting married women to teach in the public school system, she taught in Catholic parochial schools to help support her family, including Clara Jones’ endeavor to attend college. Jones’ father, Ralph Herbert Stanton, was a manager at the Standard Life Insurance Company. He eventually accepted a position with the Atlanta Life Insurance Company, where he worked until his death. Jones grew up in a highly segregated St. Louis neighborhood, but she was not daunted by the assumed, implicit Jim Crow laws; she instead regarded her young life to be privileged with all her primary mentors being African American.Education and solidarity were heavily emphasized in Jones’ family. She obtained a well-rounded education even though the St. Louis public school system was completely segregated. She grew up in an entirely African-American world, with black role-models and mentors. In high school, Jones aspired to become an elementary school teacher, even though her future salary would be slightly below white counterparts. This position would still provide a high standard of living for African Americans at that time because the income gap between white and black teachers was only slight. Jones was the first member of her family to graduate from college. St. Louis was highly segregated, but instead of attending the local, tuition-free teachers college that was designated for black students, Jones attended the Milwaukee State Teacher’s College in 1930; she was inspired by her older brothers’ stories of college life away from home at Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Jones was one of only six black students at the college. She transferred to Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia, where she majored in English and History and decided to become a librarian instead of a teacher. The president Florence Read caught notice of Jones’ typing skills and offered her a position as a typist with the new Atlanta University Library; the librarians encouraged Jones to pursue a career in librarianship. She was highly receptive to their suggestions as she had already considered this career change. Jones remained in that position until her graduation; she received her Bachelor of Arts in 1934 from Spelman and a degree in Library Science in 1938 from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.Jones began working in libraries the same year she completed her degree in Library Science. She said that at the beginning of 1938, she worked in libraries at Dillard University in New Orleans and Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Jones spent the remainder of her library career at the Detroit Public Library, retiring in 1978 as the director. She had become its director in 1970, which made her the first African American and the first woman to serve as director of a major library system in America. There was opposition to the election of Jones as director at the Detroit Public Library; the Friends of the Library had originally offered to supplement the librarian’s wages but withdrew the offer, then three people, a high ranking administrator and two of the commissioners, resigned when she was elected. Her detractors tried to challenge her authority by questioning her decisions, making decisions behind her back, and using degrading language. Her secretary, Carolyn Moseley, recalled how Jones never discussed these obstacles because that would affect how people perceived her. Moseley also recalled how Jones focused helping others become more successful by utilizing her power and resources on their behalf.The Council of the American Library Association passed a “Resolution on Racism and Sexism Awareness” during the ALA’s Centennial Conference in Chicago, July 18–24, 1976.In May 1977, Clara Stanton Jones, then president of the American Library Association, responded to the ALA Intellectual Freedom Committee’s (IFC) recommendation to rescind the ALA’s “Resolution on Racism and Sexism Awareness” because its language remained unclear. Her response was published in American Libraries, the official publication of the ALA. Jones opposed the IFC’s proposal, declaring that the resolution required further adjustments and amendments to the language before the committee considered annulment. The IFC feared that the resolution favored censorship as a means to purge library materials of racist and sexist language, thereby opposing the Library Bill of Rights pledge to sustain access to information and enlightenment despite content and to encourage libraries to challenge censorship.The ALA made the decision to deliberate the fate of the resolution and report its results at the 1977 Detroit conference. Jones asserted that the resolution did not conflict with the Library Bill of Rights, and instead promoted awareness by encouraging training and outreach programs in the libraries and library schools. In agreement with the Library Bill of Rights, she advocated for more enlightenment, not repression, to combat the effects of racism and sexism in library materials. Jones viewed the resolution as the framework, and not the final solution, for enabling librarians to confront issues that hampered “human freedom”. She argued, “The spirit of the ‘Resolution on Racism and Sexism Awareness’ is not burdened with repression; it is liberating. If the resolution is imperfect, try to make it perfect, but not by destroying it first!”The resolution was not rescinded.Jones became the director for the Detroit Public Library in 1970, making her the first African American and the first woman to serve as director of a major library system in America.She served as the first black president of the American Library Association from 1976 to 1977. During her presidency, she heavily aided the ALA adoption of a “Resolution on Racism and Sexism Awareness” to encourage librarians to raise the awareness of library patrons and staff to problems of racism and sexism.She advocated against the ALA’s Intellectual Freedom Committee’s recommendation to the ALA Executive Board that the “Resolution on Racism and Sexism Awareness” be rescinded. It was not rescinded.President Jimmy Carter appointed Jones as Commissioner to the National Commission on Libraries and Information Science in 1978. She served in this post until 1982.In 1984, Jones and Aileen Clarke Hernandez, former President of the National Organization for Women (NOW), founded the black women’s discussion group Black Women Stirring the Waters, in the San Francisco Bay Area.Jones received the Trailblazer Award in 1990 from the Black Caucus of the American Library Association, the highest award given by BCALA. The award recognizes individuals whose pioneering contributions have been outstanding and unique, and whose efforts have “blazed a trail” in the profession.Clara Stanton Jones died peacefully in her sleep on September 30, 2012 in Oakland California at the age of 99. She was survived by her three children, seven grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.Jones’s children Vinetta Jones, Stanton Jones, and Kenneth Jones founded the Albert D. and Clara Stanton Jones Scholarship fund in 2007 to provide scholarship assistance for University of Michigan School of Information master’s students, mainly those interested in urban librarianship.In 2018 Clara Stanton Jones was inducted into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame in the historical category. Research more about his great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American community leader, politician and activist.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American community leader, politician and activist. She is Vice President of Community Relations and Government Affairs for Thomson Reuters Legal business. She served as mayor of Minneapolis, Minnesota, from 1994 until 2001, the first African American and first woman to hold that position.Today in our History – May 13, 1951 – Sharon Sayles Belton (May 13, 1951) was born.Sayles Belton was born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, as one of four daughters of Bill and Ethel Sayles. After her parents separated, she lived for one year with her mother in Richfield, Minnesota, where she was the only African American in East Junior High School, then moved to south Minneapolis to live with her father and stepmother. She attended Central High School in Minneapolis. She volunteered as a candy striper at Mount Sinai Hospital, and later worked as a nurse’s aide. She served briefly a civil rights activist in the state of Mississippi.Sayles Belton attended Macalester College in Saint Paul, where she studied biology and sociology. She later worked as a parole officer with victims of sexual assault. Like her grandfather Bill Sayles, she became a neighborhood activist. In 1983, Sayles Belton was elected by the Eighth Ward to the Minneapolis City Council. She was inspired by working with mayor Donald M. Fraser. She represented the state at the 1984 Democratic National Convention, where Minnesota politician Walter Mondale was nominated for President of the United States. A member of the Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, Sayles Belton was elected city council president in 1990.In 1993, she announced her candidacy for mayor. With the help of three phone banks and a staff of ten, she was elected on a platform that included reform of the police department, the first African American and the first woman mayor in the city’s 140-year history. She defeated DFL former Hennepin County Commissioner John Derus. She was reelected in 1997, defeating Republican candidate Barbara Carlson. Sayles Belton held the position for two terms, from January 1, 1994, to December 31, 2001. The city also addressed archaic utilities billing, outdated water treatment and neighborhood flooding. By the end of the decade, Minneapolis had increased property values, the city had its first increase in population since the 1940s, and there was reversal of a “50-year economic slide.” Fraser credits Sayles Belton with stabilizing neighborhoods amid racial tensions, supporting the school system, and being an able and savvy city manager. Critics opposed the use of city subsidies for downtown development, said to total $90 million combined for the Target store and Block E.In the 2001, election Sayles Belton lost her party’s endorsement and the Democratic primary to R. T. Rybak, who received the support of the powerful Minneapolis Police Federation. After leaving the mayor’s office, Sayles Belton became a senior fellow at the Roy Wilkins Center for Human Relations and Social Justice. The center is part of the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs.Sayles Belton worked in community affairs and community involvement for the GMAC Residential Finance Corporation, headquartered in Minneapolis. In 2010, she joined Thomson Reuters as vice president of Community Relations and Government Affairs, based in Eagan, Minnesota.She is married to Steven Belton, with whom she raised three children: Kilayna, Jordan, and Coleman. Sayles Belton is involved in race equality, community and neighborhood development, public policy, women’s, family and children’s issues, police-community relations and youth development. In 1978 she co-founded the Harriet Tubman Shelter for Battered Women in Minneapolis. She is a co-founder of the National Coalition Against Sexual Assault. She contributed to the Neighborhood Revitalization Program, Clean Water Partnership, Children’s Healthcare and Hospital, the American Bar Association,[9] the Bush Foundation, the United States Conference of Mayors, the National League of Cities, and Hennepin County Medical Center by chairing or serving on their boards.• Gertrude E. Rush Distinguished Service Award presented by the National Bar Association• Rosa Parks Award, presented by the American Association for Affirmative Action• A bust of Sayles Belton was unveiled in Minneapolis City Hall on May 16, 2017, which was declared Sharon Sayles Belton day in Minnesota by Governor Mark Dayton.Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a good friend of mine back in the day when I worked and went to college in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was a good friend of mine back in the day when I worked and went to college in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. I have to say that his sister was the only person in a club atmosphere who could hold the crowd better. He was an American singer and musician. His 1981 album Breakin’ Away spent two years on the Billboard 200 and is considered one of the finest examples of the Los Angeles pop and R&B sound. The album won him the 1982 Grammy for Best Male Pop Vocal Performance. In all, he won seven Grammy Awards and was nominated for over a dozen more during his career.He also sang the theme song of the 1980s television series Moonlighting, and was among the performers on the 1985 charity song “We Are the World.”Today in our History – May 12, 1986 -Alwin Lopez Jarreau (March 12, 1940 – February 12, 2017). HBO’s Comic Relief featured him in a duet with Natalie Cole singing the song “Mr. President”, written by Joe Sterling, Mike Loveless, and Ray Reach. Jarreau was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on March 12, 1940, the fifth of six children. His father was a Seventh-day Adventist Church minister and singer, and his mother was a church pianist. Jarreau and his family sang together in church concerts and in benefits, and Jarreau and his mother performed at PTA meetings. Jarreau was student council president and Badger Boys State delegate for Lincoln High School. At Boys State, he was elected governor. Jarreau went on to attend Ripon College, where he also sang with a group called the Indigos. He graduated in 1962 with a Bachelor of Science degree in psychology. Two years later, in 1964, he earned a master’s degree in vocational rehabilitation from the University of Iowa. Jarreau also worked as a rehabilitation counselor in San Francisco and moonlighted with a jazz trio headed by George Duke. In 1967, he joined forces with acoustic guitarist Julio Martinez. The duo became the star attraction at a small Sausalito nightclub called Gatsby’s. This success contributed to Jarreau’s decision to make professional singing his life and full-time career. In 1968, Jarreau made jazz his primary occupation. In 1969, he and Martinez headed south, where Jarreau appeared at Dino’s, The Troubadour, and Bitter End West. Television exposure came from Johnny Carson, Mike Douglas, Merv Griffin, Dinah Shore, and David Frost. He expanded his nightclub appearances, performing at The Improv between the acts of such rising stars as Bette Midler, Jimmie Walker, and John Belushi. During this period, he became involved with the United Church of Religious Science and the Church of Scientology. Also, roughly at the same time, he began writing his own lyrics, finding that his Christian spirituality began to influence his work. In 1975, Jarreau was working with pianist Tom Canning when he was spotted by Warner Bros. Records. Soon he released his critically acclaimed debut album, We Got By, which catapulted him to international fame and won an Echo Award (the German equivalent of the Grammys in the United States).On Valentine’s Day 1976 he sang on the 13th episode of NBC’s Saturday Night Live, that week hosted by Peter Boyle. A second Echo Award would follow with the release of his second album, Glow. In 1978, he won his first Grammy Award for Best Jazz Vocal Performance for his album, Look to the Rainbow. One of Jarreau’s most commercially successful albums is Breakin’ Away (1981), which includes the hit song “We’re In This Love Together”. He won the 1982 Grammy Award for Best Male Pop Vocal Performance for Breakin’ Away.In 1983 he released Jarreau. It was his third consecutive #1 album on the Billboard Jazz charts, while also placing at #4 on the R&B album charts and #13 on the Billboard 200. The album contained three hit singles: “Mornin'” (U.S. Pop #21, AC #2 for three weeks), “Boogie Down” (U.S. Pop #77), and “Trouble in Paradise” (U.S. Pop #63, AC #10). In 1984 the album received four Grammy Award nominations, including for Jay Graydon as Producer of the Year (Non-Classical).In 1984, his single “After All” reached 69 on the US Hot 100 chart and number 26 on the R&B chart. It was especially popular in the Philippines. His last big hit was the Grammy-nominated theme to the 1980s American television show Moonlighting, for which he wrote the lyrics.Among other things, he was well known for his extensive use of scat singing (for which he was called “Acrobat of Scat”), and vocal percussion. He was also a featured vocalist on USA for Africa’s “We Are the World” in which he sang the line, “…and so we all must lend a helping hand.” Another charitable media event, HBO’s Comic Relief, featured him in a duet with Natalie Cole singing the song “Mr. President”, written by Joe Sterling, Mike Loveless, and Ray Reach. Jarreau took an extended break from recording in the 1990s. As he explained in an interview with Jazz Review: “I was still touring, in fact, I toured more than I ever had in the past, so I kept in touch with my audience.I got my symphony program underway, which included my music and that of other people too, and I performed on the Broadway production of Grease. I was busier than ever! For the most part, I was doing what I have always done…perform live. I was shopping for a record deal and was letting people know that there is a new album coming. I was just waiting for the right label (Verve), but I toured more than ever.” In 2003, Jarreau and conductor Larry Baird collaborated on symphony shows around the United States, with Baird arranging additional orchestral material for Jarreau’s shows. Jarreau toured and performed with Joe Sample, Chick Corea, Kathleen Battle, Gregor Praecht, Miles Davis, George Duke, David Sanborn, Rick Braun, and George Benson. He also performed the role of the Teen Angel in a 1996 Broadway production of Grease. On March 6, 2001, he received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, at 7083 Hollywood Boulevard on the corner of Hollywood Boulevard and La Brea Avenue.In 2006, Jarreau appeared in a duet with American Idol finalist Paris Bennett during the Season 5 finale and on Celebrity Duets singing with actor Cheech Marin. In 2009, children’s author Carmen Rubin published the story Ashti Meets Birdman Al, inspired by Jarreau’s music. In 2010, Jarreau was a guest on a Eumir Deodato album, with the song “Double Face” written by Jarreau, Deodato, and Nicolosi. The song was produced by the Italian company Nicolosi Productions. On February 16, 2012, Jarreau was invited to the famous Italian Festival di Sanremo to sing with the Italian group Matia Bazar.Jarreau was married twice. Jarreau and Phyllis Hall were married from 1964 until their divorce in 1968. Jarreau’s second wife Susan Elaine Player [it] (1954-2019) was fourteen years his junior. They were married from 1977 until his death in 2017 and had a son.It was reported on July 23, 2010, that Jarreau was critically ill at a hospital in France, after performing in Barcelonnette, and was being treated for respiratory problems and cardiac arrhythmias. He was conscious, in a stable condition and in the cardiology unit of La Timone hospital in Marseille, the Marseille Hospital Authority said, and he remained there for about a week for tests. In June 2012, Jarreau was diagnosed with pneumonia, which caused him to cancel several concerts in France. Jarreau made a full recovery and continued to tour extensively for the next five years until February 2017. On February 8, 2017, after being hospitalized for exhaustion in Los Angeles, Jarreau canceled his remaining 2017 tour dates. On that date, the Montreux Jazz Academy, part of the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland, announced that Jarreau would not return as a mentor to ten young artists, as he had done in 2015. On February 12, 2017, Jarreau died of respiratory failure, at the age of 76, just two days after announcing his retirement, and one month before his 77th birthday. He is interred in the Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Hollywood Hills), not far from George Duke. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American religious leader and political activist who heads the Nation of Islam (NOI).

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion is an American religious leader and political activist who heads the Nation of Islam (NOI). Earlier in his career, he served as the minister of mosques in Boston and Harlem and was appointed National Representative of the Nation of Islam by former NOI leader Elijah Muhammad.After Warith Deen Mohammed reorganized the original NOI into the orthodox Sunni Islamic group American Society of Muslims, he began to rebuild the NOI as “Final Call”. In 1981, he officially adopted the name “Nation of Islam”, reviving the group and establishing its headquarters at Mosque Maryam. The Nation of Islam is an organization which the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) describes as black nationalist and a hate group. Farrakhan’s antisemitic rhetoric has been condemned by the Southern Poverty Law Center, Anti-Defamation League (ADL), and other monitoring organizations. Also according to the SPLC, the NOI promotes a “fundamentally anti-white theology” amounting to an “innate black superiority over whites”. Some of his remarks have been considered homophobic.[6] Farrakhan has disputed such assertions on many occasions including the SPLC characterizations.In October 1995, he organized and led the Million Man March in Washington, D.C. Due to health issues, he reduced his responsibilities with the NOI in 2007. However, he has continued to deliver sermons[13] and speak at NOI events. In 2015, he led the 20th Anniversary of the Million Man March: Justice or Else. He was banned from Facebook in 2019 along with other public figures considered to be extremists.Today in our History – May 11, 1933 – Louis Farrakhan Sr. (/ˈfɑːrəkɑːn/; born Louis Eugene Walcott, May 11, 1933), formerly known as Louis X.Farrakhan was born Louis Eugene Walcott on May 11, 1933, in The Bronx, New York City, the younger of two sons of Sarah Mae Manning (January 16, 1900 – November 18, 1988) and Percival Clark, immigrants from the Anglo-Caribbean islands. His mother was born in Saint Kitts, while his father was Jamaican. The couple separated before their second son was born, and Farrakhan says he never knew his biological father.[16] In a 1996 interview with Henry Louis Gates Jr., he speculated that his father, “Gene”, may have been Jewish. After the end of his parents’ relationship, his mother moved in with Louis Walcott from Barbados, who became his stepfather. After his stepfather died in 1936, the Walcott family moved to Boston, where they settled in the largely African-American neighborhood of Roxbury.Walcott received his first violin at the age of five and by the time he was 12 years old, he had been on tour with the Boston College Orchestra.[16][19] A year later, he participated in national competitions and won them. In 1946, he was one of the first black performers to appear on the Ted Mack Original Amateur Hour, where he also won an award. Walcott and his family were active members of the Episcopal St. Cyprian’s Church in Roxbury.Walcott attended the Boston Latin School, and later the English High School, from which he graduated. He completed three years at Winston-Salem Teachers College, where he had a track scholarship.In 1953, Walcott married Betsy Ross (later known as Khadijah Farrakhan) while he was in college.Due to complications from his new wife’s first pregnancy, Walcott dropped out after completing his junior year of college to devote time to his wife and their child. Farrakhan has nine children in total.The Nation of Islam under the leadership of the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan is the catalyst for the growth and development of Islam in America. Founded in 1930 by Master Fard Muhammad and led to prominence from 1934 to 1975 by the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, the Nation of Islam continues to positively impact the quality of life in America.Minister Louis Farrakhan, born on May 11, 1933 in Bronx, N.Y., was reared in a highly disciplined and spiritual household in Roxbury, Massachusetts. Raised by his mother, a native of St. Kitts, Louis and his brother Alvan learned early the value of work, responsibility and intellectual development.Having a strong sensitivity to the plight of Black people, his mother engaged her sons in conversations about the struggle for freedom, justice and equality. She also exposed them to progressive material such as the Crisis magazine, published by the NAACP.Popularly known as “The Charmer,” he achieved fame in Boston as a vocalist, calypso singer, dancer and violinist. In February 1955, while visiting Chicago for a musical engagement, he was invited to attend the Nation of Islam’s Saviours’ Day convention.Although music had been his first love, within one month after joining the Nation of Islam in 1955, Minister Malcolm X told the New York Mosque and the new convert Louis X that Elijah Muhammad had said that all Muslims would have to get out of show business or get out of the Temple. Most of the musicians left Temple No. 7, but Louis X, later renamed Louis Farrakhan, chose to dedicate his life to the Teachings of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad.The departure of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad in 1975 and the assumption of leadership by Imam W. Deen Mohammed brought drastic changes to the Nation of Islam. After approximately three years of wrestling with these changes, and a re-appraisal of the condition of Black people and the value of the Teachings of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, Minister Farrakhan decided to return to the teachings and program with a proven ability to uplift and reform Blacks.His tremendous success is evidenced by mosques and study groups in over 120 cities in America, Europe, the Caribbean and missions in West Africa and South Africa devoted to the Teachings of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. In rebuilding the Nation of Islam, Minister Farrakhan has renewed respect for the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, his Teachings and Program.At 80 years of age, Minister Farrakhan still maintains a grueling work schedule. He has been welcomed in a countless number of churches, sharing pulpits with Christian ministers from a variety of denominations, which has demonstrated the power of the unity of those who believe in the One God.He has addressed diverse organizations, been received in many Muslim countries as a leading Muslim thinker and teacher, and been welcomed throughout Africa, the Caribbean and Asia as a champion in the struggle for freedom, justice and equality.In 1979, he founded The Final Call, an internationally circulated newspaper that follows in the line of The Muhammad Speaks. In 1985, Minister Farrakhan introduced the POWER concept. In 1988, the resurgent Nation of Islam repurchased its former flagship mosque in Chicago and dedicated it as Mosque Maryam, the National Center for the Re-training and Re-education of the Black Man and Woman of America and the World. In 1991, Minister Farrakhan reintroduced the Three Year Economic Program, first established by the Honorable Elijah Muhammad to build an economic base for the development of Blacks through business ventures. In 1993, Minister Farrakhan penned the book, “A Torchlight for America,” which applied the guiding principles of justice and good will to the problems perplexing America. In May of that year, he traveled to Libreville, Gabon to attend the Second African-African American Summit where he addressed African heads of state and delegates from America. In October of 1994, Minister Farrakhan led 2,000 Blacks from America to Accra, Ghana for the Nation of Islam’s first International Saviours’ Day. Ghanaian President Jerry Rawlings officially opened and closed the five-day convention.The popular leader and the Nation of Islam repurchased farmland in Dawson, Georgia and enjoyed a banner year in 1995 with the successful Million Man March on the Mall in Washington, D.C., which drew nearly two million men. Minister Farrakhan was inspired to call the March out of his concern over the negative image of Black men perpetuated by the media and movie industries, which focused on drugs and gang violence. The Million Man March established October 16 as a Holy Day of Atonement, Reconciliation and Responsibility. Minister Farrakhan took this healing message of atonement throughout the world during three World Friendship Tours over the next three years. His desire was to bring solutions to such problems as war, poverty, discrimination and the right to education. Minister Farrakhan would return to the Mall on Washington, D.C. in 2000 convening the Million Family March, where he called the full spectrum of members of the human family to unite according to the principle of atonement. Minister Farrakhan performed thousands of weddings, as well as renewed the vows of those recommitting themselves in a Marriage Ceremony.As part of the major thrust for true political empowerment for the Black community, Minister Farrakhan re-registered to vote in June 1996 and formed a coalition of religious, civic and political organizations to represent the voice of the disenfranchised on the political landscape. His efforts and the overwhelming response to the call of the Million Man March resulted in an additional 1.7 million Black men voting in the 1996 presidential elections. In July 1997, the Nation of Islam, in conjunction with the World Islamic People’s Leadership, hosted an International Islamic Conference in Chicago. A broad range of Muslim scholars from Europe, Asia, Africa and the Middle East, along with Christian, Jewish and Native American spiritual leaders participated in the conference.Following the September 11, 2001 attacks against the United States, Minister Farrakhan was among the international religious voices that called for peace and resolution of conflict. He also wrote two personal letters to President George Bush offering his counsel and perspective on how to respond to the national crisis. He advised President Bush to convene spiritual leaders of various faiths for counsel. Prior to the war on Iraq, Minister Farrakhan led a delegation of religious leaders and physicians to the Middle East in an effort to spark the dialogue among nations that could prevent war.Marking a new milestone in a life that has been devoted to the uplift of humanity, Minister Farrakhan launched a prostate cancer foundation in his name May 10-11, 2003. First diagnosed in 1991 with prostate cancer, he survived a public bout and endured critical complications after treatment that brought him 180 seconds away from death.In July of that year, Minister Farrakhan accepted the request to host the first of a series of summits centered on the principles of reparations. Nearly 50 activists from across the country answered his call to discuss operational unity within the reparations movement for Black people’s suffering in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Culminating the Nation of Islam’s Saviours’ Day convention in February 2004, Minister Farrakhan delivered an international address entitled, “Reparations: What does America and Europe Owe? What does Allah (God) promise?” stepping further into the vanguard position of leadership calling for justice for the suffering masses of Black people and all oppressed people throughout the world.On May 3, 2004, Minister Farrakhan held an international press conference at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. themed, “Guidance to America and the World in a Time of Trouble.” The press conference sought to expose the plans and schemes of President George W. Bush and his neo-conservative advisers who plunged American soldiers into worldwide conflict with the occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq. This international press conference was translated into Arabic, French and Spanish.In October 2005, after months of a demanding schedule traveling throughout the U.S., Minister Farrakhan called those interested in establishing a programmatic thrust for Black people in America and oppressed people across the globe to participate in the Millions More Movement, which convened back at the National Mall in Washington, D.C. on the 10th Anniversary of the Historic Million Man March. The Millions More Movement involved the formation of 9 Ministries that would deal with the pressing needs of our people. Also in 2005, Minister Louis Farrakhan was voted as BET.com‘s “Person of The Year” as the person users believed made “the most powerful impact on the Black community over the past year.”In April 2006, Minister Farrakhan led a delegation to Cuba to view the emergency preparedness system of the Cuban people, in the wake of the massive failure to prevent the loss of human life after Hurricane Katrina in August 2005.In January 2007, the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan underwent a major 14-hour pelvic exoneration. In just a few weeks, and as a testament to the healing power of God, Minister Farrakhan stood on stage at Ford Field in Detroit, Michigan on February 25, 2007 to deliver the first of several speeches that year with the theme “One Nation Under God.”On October 19, 2008, after nearly a year of extensive repairs and restoration, Minister Farrakhan opened the doors and grounds of Mosque Maryam to thousands of people representing all creeds and colors during a much anticipated Re-dedication Ceremony themed “A New Beginning.” This day also served as the commemoration of the 13th Anniversary of the Historic Million Man March and Holy Day of Atonement.The prayers of spiritual leaders representing the three Abrahamic faiths—Judaism, Christianity and Islam—were offered to bless this momentous affair. Those who were present that day, and who watched live via internet webcast throughout the world, witnessed Minister Farrakhan’s message of unity and peace for the establishment of a universal government of peace for all of humanity. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American artist and founding president of the Charleston, South Carolina, branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was an American artist and founding president of the Charleston, South Carolina, branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Because of his race, he was excluded from the whites-only artistic movement known as the Charleston Renaissance.Today in our History – May 10, 1931 – Edwin Augustus Harleston (March 14, 1882 – May 10, 1931) died.He was born in Charleston, South Carolina, on March 14, 1882. He was one of five surviving children of Louisa Moultrie Harleston and Edwin Gaillard Harleston, a prosperous former coastal schooner captain who owned the Harleston Funeral Home . His mother traced her lineage through several generations of free people of color, while his father was descended from a white planter and one of his slaves.Harleston won a scholarship to study at the Avery Normal Institute, from which he graduated as valedictorian in 1900. He went on to Atlanta University, where he studied chemistry and sociology and took courses with W. E. B. Du Bois, who became a lifelong friend. After graduating in 1904, Harleston stayed on for a year as a teaching assistant in both sociology and chemistry while planning the next step in his education. Although he was admitted to Harvard University, he decided instead to attend the Boston Museum of Fine Art’s school. There he studied under the painters William McGregor Paxton and Frank Weston Benson from 1905 to December 1912. Edwin also attended the Art Institute of Chicago over the summer.Harleston returned to South Carolina in 1913 to help his father run the funeral home, continuing to do so until 1931, the year both he and his father died. He became active in local civil rights groups and in 1917 rose to be president of Charleston’s newly formed branch of the NAACP. One campaign he led succeeded in getting the local public school system to hire black teachers.Harleston painted in a realist style that was influenced by both his Boston training and his wife Elise Forrest Harleston’s photographic work. He mostly painted portraits, often on commission, and his sitters included notables such as Grace Towns, who later became the first African-American woman elected to the Georgia General Assembly; philanthropist Pierre S. du Pont; and Edward Twitchell Ware, a former president of Atlanta University. He also painted genre scenes of the daily life of Charleston’s African-American citizens, especially its rising middle class, as well as landscapes of South Carolina Lowcountry. Out of step with the rising modernism of the 1920s, he saw himself as continuing in the tradition of Henry Ossawa Tanner by portraying black people and their lives realistically instead of as caricatures or stereotypes. Harleston was described by W. E. B. Du Bois as the “leading portrait painter of the race” even though his responsibility for helping to run the funeral home meant he could never devote himself to being a painter full-time.In 1920, Harleston married photographer Elise Forrest, with whom he opened a studio across the street from the funeral home. This studio, which had both workspace and a public gallery to promote their artwork, was the first such public art establishment for Charleston’s African-American citizens.Harleston often used Elise’s photographs as the basis of his paintings and drawings; one of his best-known works, Miss Sue Bailey with the African Shawl, is based on a photograph by Elise. A three-quarter length seated portrait in dark colors and muted light, the painting exemplifies Harleston’s commitment to portraying his sitters with dignity. Edwin was actually so pleased with the painting that he entered it in the 1930 Harmon Foundation Awards.Starting in 1930, Harleston helped artist Aaron Douglas paint his Symbolic Negro History murals for Fisk University; these are now considered among Douglas’s most important works. This project was completed in 1930, the year before Harleston died. In 1930, Harleston painted Douglas’s portrait with the unfinished mural in the background, typically emphasizing the sitter’s profession and character while avoiding any suggestion of the picturesque. This mural is vastly different from his usual painting style, which consisted of muted colors like those seen in the painting of Miss Sue Bailey with the African Shawl. The colors he used in the mural showcase a much more vibrant range of shade, which display his range as an artist, and they way he could adjust to work with other other artists.Harleston won a number of awards for his work, including the top prize in NAACP-sponsored contests in 1925 (A Colored Grand Army Man) and 1931 (Ouida) and the William E. Harmon Foundation’s Alain Locke Prize for portrait painting, also in 1931 (The Old Servant).Despite this modest success, Harleston was largely excluded from the dominantly white artistic circles of the Charleston Renaissance with which his work is today associated. Only writer Julia Peterkin, who won a Pulitzer Prize for her writing about African-American life, appears to have visited Harleston. Although writer DuBose Heyward based a character on him in his novel Mamba’s Daughters, it seems they never met in person. Racial prejudice and segregation thwarted several potential commissions and blocked a planned 1926 exhibition of his work at the Charleston Museum that had been organized by museum director Laura Bragg and promoted by the city’s mayor, Thomas Porcher Stoney.By 1930, the funeral home business was suffering from the Great Depression. Harleston undertook a series of lectures at black colleges to earn money.[4]In April 1931, Harleston’s father died of pneumonia, and Harleston himself (who is said to have kissed his dying father goodbye) succumbed to the same ailment less than a month later at the age of 49.Harleston’s paintings are in the collections of the Gibbes Museum of Art (Charleston), the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture (Charleston), the Savannah (GA) College of Art and Design Museum of Art, and the California African American Museum.Harleston’s papers are held by the South Carolina Historical Society and Emory University’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!

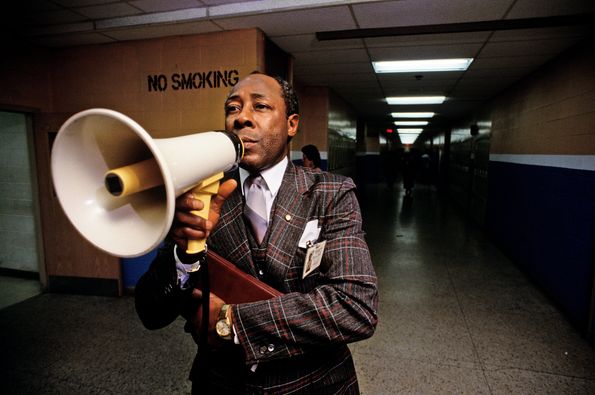

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was the principal of Eastside High School in Paterson, New Jersey.

GM – FBF – Today’s American Champion was the principal of Eastside High School in Paterson, New Jersey. He is also the subject of the 1989 film Lean on Me, starring Morgan Freeman. He gained public attention in the 1980s for his unconventional and controversial disciplinary measures as the principal of Eastside High.Today in our History – May 8, 1938 – Joe Louis Clark was born.Clark was seen as an educator who was not afraid to get tough on difficult students, one who would often carry a bullhorn or a baseball bat at school. During his time as principal, Clark expelled over 300 students who were frequently tardy or absent from school, sold or used drugs in school, or caused trouble in school.Clark’s practices did result in slightly higher average test scores for Eastside High during the 1980s. After his tenure as principal of Eastside High, Clark later served as director of the Essex County Detention House in Newark, New Jersey, a juvenile detention facility. Time magazine’s cover article notes that Clark’s style as principal was primarily disciplinarian in nature, focused on encouraging school pride and good behavior, although Clark was also portrayed as a former social activist in the film Lean on Me. “Clark’s use of force may rid the school of unwanted students,” commented Boston principal Thomas P. O’Neill Jr., “but he also may be losing kids who might succeed.” George McKenna, former principal of Washington Preparatory High School in Los Angeles, often cited as a contemporary of Joe Clark as a school reformer with a similarly outgoing approach, was also critical. “Our role is to rescue and to be responsible,” McKenna told Time. “If the students were not poor black children, Joe Clark would not be tolerated.”Other educators defended and praised Clark. “You cannot use a democratic and collaborative style when crisis is rampant and disorder reigns,” said Kenneth Tewel, a former principal. “You need an autocrat to bring things under control.” Some critics focused on the fact that while Clark had reestablished cleanliness and order, education scores had not substantially improved, which resulted in Eastside High being taken over by the state one year after Clark’s departure in 1991. Separate criticism focused on the social impact of expelling delinquent students to improve test scores, claiming that “tossing out the troublesome low achievers” simply moved the problems from the school onto the street. Clark defended the practice, saying teachers should not have to waste their time on students who do not want to learn.However, Time noted that the national dropout rate for such students remained high across the country, with few alternatives available, and that each inner city school that had been able to reverse the trend had done so through “a bold, enduring principal” such as Clark who was “able to maintain or restore order without abandoning the students who are in trouble.” Clark grew up in Newark, New Jersey and attended Central High School. Clark was also the father of Olympic track athletes Joetta Clark Diggs and Hazel Clark, and the father-in-law of Olympic track athlete Jearl Miles Clark. His son, JJ Clark, was their coach.He resided in Newberry, Florida during his retirement. Clark died following a long illness on December 29, 2020 at the age of 82. Research more about this great American Champion and share it with your babies. Make it a champion day!