GM – FBF – My fellow Wilmington, North Carolina native

Meadowlark Lemon is a true national treasure. I watched him play for the Harlem

Globetrotters when I was growing up and his skill with the basketball and

dedication to the game were an inspiration not only to me, but to kids all

around the world.

Michael Jordan NBA Hall of Fame Basketball Player

Remember – “You must understand as a kid of color in those

days, the Harlem Globetrotters were like being movie stars.”

Wilt Chamberlain NBA Hall of Fame Basketball Player

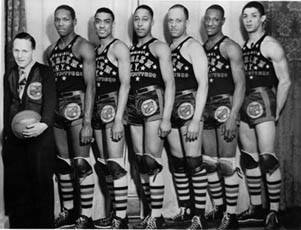

Today in our History – February 10, 1948 – THE DATE WAS SET FOR THE MINNEAPOLIS LAKERS AND THE HARLEM GLOBETROTTERS TO PLAY (February 19, 1948) IN WHICH THE GLOBETROTTERS WON! The Harlem Globetrotters originated on the south side of Chicago, Illinois, in the 1920s, where all the original players were raised. In spite of the team’s name, the squad was born 800 miles west of Harlem in the south side of Chicago. In 1926, a group of former basketball players from Chicago’s Wendell Phillips High School reunited to play for the Giles Post American Legion basketball team that barnstormed around the Midwest. The following year, the team became known as the Savoy Big Five while playing home games as pre-dance entertainment at Chicago’s newly opened Savoy Ballroom The Globetrotters began as the Savoy Big Five, one of the premier attractions of the Savoy Ballroom opened in November 1927, a basketball team of African-American players that played exhibitions before dances. In 1928, several players left the team in a dispute. That autumn, several of the players, led by Tommy Brookins, formed a team called the “Globe Trotters” and toured Southern Illinois that spring. Abe Saperstein became involved with the team as its manager and promoter. By 1929, Saperstein was touring Illinois and Iowa with his basketball team called the “New York Harlem Globe Trotters”. Saperstein selected Harlem, New York, New York, as their home city since Harlem was considered the center of African-American culture at the time and an out-of-town team name would give the team more of a mystique. In fact, the Globetrotters did not play in Harlem until 1968, four decades after the team’s formation.

The Globetrotters were perennial participants in the World Professional Basketball Tournament, winning it in 1940. In a heavily attended matchup a few years later, the 1948 Globetrotters-Lakers game, the Globetrotters made headlines when they beat one of the best white basketball teams in the country, the Minneapolis Lakers (now the Los Angeles Lakers). The Globetrotters gradually worked comic routines into their act—a direction the team has credited to Reece “Goose” Tatum, who joined in 1941—and eventually became known more for entertainment than sports. Once one of the most famous teams in the country, the Globetrotters were eventually eclipsed by the rise of the National Basketball Association, particularly when NBA teams began fielding African-American players in the 1950s. In 1950, Harlem Globetrotter Chuck Cooper became the first black player to be drafted in the NBA by Boston and teammate Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton became the first African-American player to sign an NBA contract when the New York Knicks purchased his contract from the Globetrotters. The Globetrotters’ acts often feature incredible coordination and skillful handling of one or more basketballs, such as passing or juggling balls between players, balancing or spinning balls on their fingertips, and making unusual difficult shots.

In 1952, the Globetrotters invited Louis “Red” Klotz to create a team to accompany them on their tours. This team, the Washington Generals (who also played under various other names), were the Globetrotters’ primary opponents up until 2015. The Generals were effectively stooges for the Globetrotters, with the Globetrotters handily defeating them in thousands of games.

Many famous basketball players have played for the Globetrotters. Greats such as “Wee” Willie Gardner, Connie “The Hawk” Hawkins, Wilt “The Stilt” Chamberlain, and Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton later went on to join the NBA. The Globetrotters signed their first female player, Olympic gold medalist Lynette Woodard, in 1985. The Globetrotters have featured 13 female players in their illustrious history. Baseball Hall of Famers Ernie Banks, Bob Gibson, and Ferguson Jenkins also played for the team at one time or another. Because the majority of the team players have historically been African American, and as a result of the buffoonery involved in many of the Globetrotters’ skits, they drew some criticism during the Civil Rights era. The players were accused by some civil-rights advocates of “Tomming for Abe”, a reference to Uncle Tom and Jewish owner Abe Saperstein. However, prominent civil rights activist Jesse Jackson (who would later be named an Honorary Globetrotter) came to their defense by stating, “I think they’ve been a positive influence… They did not show blacks as stupid. On the contrary, they were shown as superior.” In 1995, Orlando Antigua became the first Hispanic player on the team. He was the first non-black player on the Globetrotters’ roster since Bob Karstens played with the squad in 1942–43. The Harlem Globetrotters have been featured in several of their own films and television series and still are a crowd favorite today. Research more about this American Iconic team and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!