GM – FBF – I always enjoy telling any story about my beloved New

Jersey, born in Camden, raised in Trenton and owned property in Trenton,

Willingboro and Edgewater Park. My family members still reside in Mercer,

Burlington, Camden and Atlantic Counties. Today’s story has a link in

Willingboro to the famed track family of the Lewis’s. We know of Carl and

Sister Carol who passed on Trenton Central High School for the ‘boro. Did you

know that their mother Evelyn Lawler Lewis, attended Tuskegee on a track-and-field

scholarship, and competed for the U.S. at the 1951 Pan American Games? Injuries

prevented her participation in the 1952 Olympics; at that time she was one of

the top three hurdlers in the world. She taught school, coached sports,

developed physical education programs, and co-founded the Willingboro Track

Club (Burlington, NJ) in 1969. Today’s story is about her Track Coach at

Tuskegee. Enjoy!

Remember – “Over my career I taught toughness and determination,

if I had the resources that the other schools we competed against had, we would

have been hard to beat for decades” – Coach Cleveland Leigh Abbott

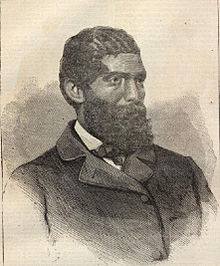

Today in our History – December 9, 1892 – Cleveland Leigh Abbott

was born in Yankton, South Dakota. He is most remembered for his coaching

career at Tuskegee Institute (now University) in Alabama.

Abbott was the son of Elbert and Mollie Brown Abbott who moved

to South Dakota from Alabama in 1890. He graduated from Watertown High School,

Watertown, South Dakota, in 1912 and then from the South Dakota State University

at Brookings in 1916. Abbott earned 16 varsity athletic awards during his

collegiate career.

Students residing in Abbott Hall, one of the new residential

halls dotting the SDSU campus, should be schooled on the significance of the

building’s namesake.

The class of 1916 featured Cleveland Leigh Abbott. Better known

as “Cleve,” his impact at South Dakota State was felt long after he left the

College on the Hill.

He was a four-sport star, lettering in track, football,

basketball, and baseball. He went on to become a legendary coach and was

inducted to several halls of fame, including SDSU. However, his most notable

achievement was his advancement of women’s sports, particularly

African-Americans.

Abbott’s destiny was put in motion a few months later when SDSU

President Ellwood Perisho attended a meeting in New York City on the

advancement of African-Americans. After the conference, he met Tuskegee

Institute President Booker T. Washington on the train.

Washington informed Perisho that he wanted to start a sports

program if he was to hold the interest of young folks attending Tuskegee and

attract greater numbers to the school.

When quizzed if he had any young men who might qualify as a

sports director, Perisho told him about Abbott, but cautioned that he was only

a freshman. Washington replied that if Abbott worked and studied hard, he could

come to Tuskegee as its sports director when he graduated from SDSU.

When Perisho returned to Brookings, he contacted Abbott about

Washington’s proposal, and in response, “Cleve” committed himself to excellence

on the field and in the classroom.

The 172-pound Abbott earned all-state football honors four

straight years, including one year being named all-northwestern center. He was

the starting center on the basketball team and was team captain as a senior. In

track, he ran the anchor leg on the relay team.

Abbott’s future was in doubt as a junior when he learned that

Washington had died. However, during his senior year, Washington’s secretary

discovered a memo of agreement for Abbott’s employment and enclosed a contract

for him to come to Tuskegee.

In 1916 Cleveland Abbott married Jessie Harriet Scott (1897–1982). They had one

daughter, Jessie Ellen, who in 1943 became the first coach of the women’s track

team at Tennessee State University in Nashville.

Arriving at the famous Alabama school, Abbott was assigned to teach various

phases of the dairy business to agricultural students and serve as an assistant

coach.

His college duties were postponed, though, when the United States

entered World War I. As a lieutenant, he was the regimental intelligence

officer attached to the 336th Infantry Company of the 92nd Division. He saw

action at the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in 1918. When the armistice was declared,

it was Abbott who carried the message of cease-fire from his colonel to the

troops. Abbott was later a commissioned officer in the Army Reserve. (The US

Army Reserve Center at Tuskegee is now named the Cleveland Leigh Abbott

Center.)

After the war, Abbott joined the faculty of Kansas Vocational School in Topeka,

where he coached and was commandant of cadets.

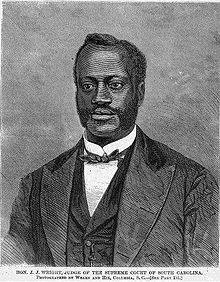

In 1923 Cleveland Abbott was hired as an agricultural chemist

and athletic director at Tuskegee Institute, a job that had been personally

offered to him by Booker T. Washington in 1913 on the condition that he

successfully earn his B.A. degree. As athletic director Abbott was expected to

coach the Institute’s football team. During Abbott’s 32-year career, the

Tuskegee team had a 202–95–27 record including six undefeated seasons;

positions he held until his death in 1955.

In 32 seasons, Abbott’s gridiron record was 203-95-15. His teams claimed 12

conference titles and six mythical National Black College championships. In

1954, he was the first African-American college football coach to rack up 200

victories.

Abbott also started the women’s track and field program at

Tuskegee in 1937. The team was undefeated from 1937 to 1942. Six of his

athletes competed on U.S. Olympic track teams, among the notable female

athletes he coached were Alice Coachman, Mildred McDaniel, and Nell Jackson.

Coachman was the first African-American woman to win a gold medal, taking the

high jump title at the 1948 Olympic Games in London. McDaniel repeated the feat

in 1956 with a world-record jump of five feet, nine inches at the Helsinki

Olympics.

From 1935 to 1955, Abbott’s outdoor track and field teams won 14

national titles, including eight consecutive. His squads captured 21

international AAU track and field crowns. Individually, Tuskegee athletes brought

home 49 indoor and outdoor titles with six making Olympic track and field

teams.

Abbott served on the women’s committee of the old National AAU

(USA Track and Field predecessor) and twice was on the U.S. Olympic Track and

Field Committee. He is also a member of the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame, and is

one of the founders of the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference

Basketball Tournament.

Abbott is credited with being one of the pioneer coaches of

women’s track and field for more than four decades. He is said to have

developed the program that opened track and field to women in the United

States.

Abbott was inducted into the South Dakota State University Hall

of Fame in 1968, the Tuskegee University Hall of Fame in 1975, the Southern

Intercollegiate Athletic Conference Hall of Fame in 1992, the Alabama Sports

Hall of Fame in 1995, and the USA Track and Field Hall of Fame in 1996. Also in

1996, in recognition of his outstanding contributions to athletics, the

Tuskegee University Football Stadium were renamed the Cleveland Leigh Abbott

Memorial Alumni Stadium.

Another female track and field standout was Evelyn Lawler Lewis,

mother of Olympic track great Carl Lewis. A 1949 Tuskegee graduate, Lewis named

her second son, Cleveland Abbott, after him. After college, she went on to

compete in the 1951 Pan American Games in Argentina, and like “Cleve,” she also

turned to coaching.

Lewis says Abbott was well ahead of his time, from coaching to

teaching and training techniques. What’s more, she says, Abbott inspired his

athletes.

“He made us believe we could

be something,” she explains. “His main theme—what he always talked about—was

‘you can do it.’ You can do what you want. You can be as good as you want. He

wasn’t a driving-type of coach—he was a motivator.”

Cleveland Leigh Abbott died at the Veterans Hospital in Tuskegee on April 14,

1955 and was buried in the Tuskegee University Campus Cemetery at Tuskegee,

Alabama. Research more about this great American and share with your babies.

Make it a champion day!