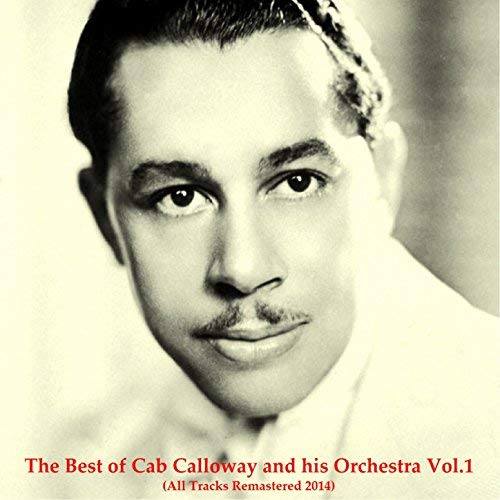

GM – FBF – Today’s story spans a life time of being up front and on stage from the Big Band Era to doing a MTV Video with Janet Jackson in the 1990’s. This artist played with the best and would not change his Image for anyone. Some say he was arrogant and others a true to his race genius. Enjoy!

Remember –“A movie and a stage show are two entirely different things. A picture, you can do anything you want. Change it, cut out a scene, put in a scene, take a scene out. They don’t do that on stage.” Cab Calloway

Today in History – November 18,

1994 – Cabell “Cab” Calloway III died. He was voted the 39th out of 100

Greatest American Band Leaders (BLACK or WHITE) of “ALL – TIME”!

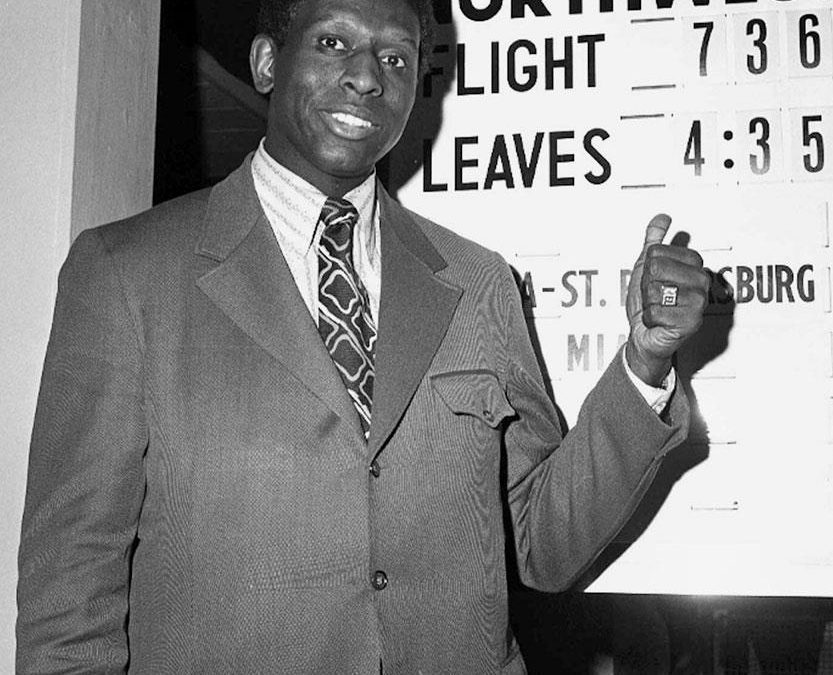

Cab Calloway, byname of Cabell Calloway III, (born December 25, 1907,

Rochester, New York, U.S.—died November 18, 1994, Hockessin, Delaware),

American bandleader, singer, and all-around entertainer known for his exuberant

performing style and for leading one of the most highly regarded big bands of

the swing era.

After graduating from high school, Calloway briefly attended a law school in Chicago but quickly turned to performing in nightclubs as a singer. He began directing his own bands in 1928 and in the following year went to New York City. There he appeared in an all-black musical, Fats Waller’s Connie’s Hot Chocolates, in which he sang the Waller classic “Ain’t Misbehavin’.”

In 1931 he was engaged as a bandleader at the Cotton Club; his orchestra, along with that of Duke Ellington’s, became one of the two house bands most associated with the legendary Harlem nightspot. In the same year, Calloway first recorded his most famous composition, “Minnie the Moocher,” a song that showcased his ability at scatsinging. Other Calloway hits from the 1930s include “Kickin’ the Gong Around,” “Reefer Man,” “The Lady with the Fan,” “Long About Midnight,” “The Man from Harlem,” and “Minnie the Moocher’s Wedding Day.”

Calloway was an energetic and humorous entertainer whose performance trademarks included eccentric dancing and wildly flinging his mop of hair; his standard accoutrementsincluded a white tuxedo and an oversized baton. He was a talented vocalist with an enormous range and was regarded as “the most unusually and broadly gifted male singer of the ’30s” by jazz scholar Gunther Schuller. Although his band rose to fame largely on the strength of his personal appeal, some critics felt that Calloway’s antics drew focus away from one of the best assemblages of musicians in jazz.

Calloway led a tight, professional unit during the early 1930s, but many regard his band of 1937–42 to be his best. Featured sidemen during those years included legendary jazz players such as pianist Bennie Payne, saxophonists Chu Berry and Ike Quebec, trombonist-vibraphonist Tyree Glenn, drummer Cozy Cole, and trumpeters Dizzy Gillespie, Doc Cheatham, Jonah Jones, and Shad Collins. The decline in popularity of big bands forced Calloway to disband his orchestra in 1948, and he continued for several years with a sextet.

Calloway also had a successful side career as an actor. He appeared in several motion pictures, including The Big Broadcast (1932), Stormy Weather (1943), Sensations of 1945 (1944), and The Cincinnati Kid (1965). George Gershwin had conceived the role of “Sportin’ Life” in his 1935 jazz opera Porgy and Bess for Calloway; the entertainer finally got his chance at the part during a heralded world tour of the show in 1952–54. In the 1960s, Calloway appeared on Broadway and on tour in Hello, Dolly!, portraying the role of Horace Vandergelder opposite Pearl Bailey as Dolly Levi, and he again starred on Broadway in the 1970s in the hit musical Bubbling Brown Sugar.

His best-known acting performance was also his last, as a jive-talking music promoter in director John Landis’s comedy The Blues Brothers (1980). The film featured Calloway singing “Minnie the Moocher” every bit as energetically and eccentrically as he had performed it in 1931. Research more about Black American Band leaders and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!