GM – FBF – Today’s story is about the legacy of Black Baseball players who came from the Negro leagues and make it to the Major Leagues starting with Jackie Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers story. You may feel like I do that many a Negro baseball player had a lot more talent than Jackie but could they handle the day to day abuse that was given to Jackie everywhere he played. My question this morning for you is simple, the Dodgers and Red Sox are currently playing in the 2018 World Series, the first time that these two teams have meet in a World Series with the name “Dodgers” Brooklyn had a team back in 1916 but they were called the Robins and the Red Sox played their home games at the Boston Braves park instead of Fenway Park to draw more seating capacity. Did you know that the Red Sox were the last major league baseball team to intergrade? Yes they did their best to try and win without a Black player but they realized in order to be competitive they had to and this is the story of the person they selected to wear the Boston Uniform. Enjoy!

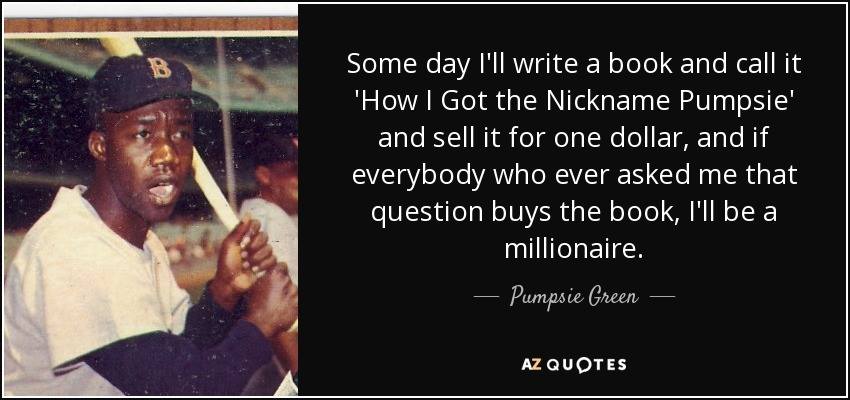

Remember – Someday I’ll write a book and call it ‘How I Got the Nickname Pumpsie’ and sell it for one dollar, and if everybody who ever asked me that question buys the book, I’ll be a millionaire. – Pumpsie Green

Today in our History – October 27, 1933 – Elijah Jerry

Green

Jr. was born.

He’s been termed a “reluctant pioneer.” All Pumpsie Green wanted to do was play professional baseball. He didn’t even aspire to the major leagues at first, and would have been content playing for his hometown Oakland Oaks in the Pacific Coast League. That said, Pumpsie Green took pride in the fact that he helped accomplish the integration of the Boston Red Sox, the last team in the majors to field an African American ballplayer.

He was born on October 27, 1933, as Elijah Jerry Green Jr. All

the standard reference books list his place of birth as Oakland, but he himself

said, “I wasn’t born in Oakland. I was born in Boley, Oklahoma. We was all born

in Oklahoma.”

The elder Elijah Green was reportedly a pretty good athlete, but had a family

to care for during the Depression and work took precedence. “He was a farmer,”

Green said in a 2009 interview, “We came out here to California when I was

eight or nine years old. He worked at the Oakland Army Base.” After the war,

Mr. Green worked for the city of Richmond, in the public works department. “He

was a garbage man,” Pumpsie explained. His wife, Gladys, worked mostly as a

homemaker before World War II, and during the war as a welder on the docks in

Oakland. As the children grew older, she became a nurse in a convalescent home.

Pumpsie played baseball from grade school on up and became a switch-hitter at an early age. He was 13 when Jackie Robinson broke into the major leagues in 1947, but Brooklyn was a long way from California. The Pacific Coast League integrated in 1948, and, to top it off, the barnstorming Jackie Robinson All-Stars came to Oakland after the ’48 season was over. Pumpsie said, “I scraped up every nickel and dime together I could find. And I was there. I had to see that game…I still remember how exciting it was.” Green was a big Oaks fan, getting to the Emeryville ballpark as often as he could, and listening on the radio when he couldn’t: “I followed a whole bunch of people on that team. It was almost a daily ritual. ….When I got old enough to wish, I wished I could play for the Oakland Oaks.” Pumpsie began to model his play after Artie Wilson, the left-handed-hitting shortstop who in 1949 became the first black player on the Oaks, and led the league both in hitting and stolen bases.

Pumpsie Green signed his 1959 contract in Scottsdale on February 25, suited up in a Red Sox uniform, and immediately took part in his first workout. Roger Birtwell’s Boston Globe story began, “The Boston Red Sox – in spring training, at least – today broke the color line.”

Green lived an isolated existence, separated from his teammates. It was a pathetic situation. Boston Globe writer Milton Gross depicted the imposed isolation: “From night to morning, the first Negro player to be brought to spring training by the Boston Red Sox ceases to be a member of the team he hopes to make as a shortstop.” Segregation, wrote Gross, “comes in a man’s heart, residing there like a burrowing worm. It comes when a man wakes alone, eats alone, goes to the movies every night alone because there’s nothing more for him to do and then, in Pumpsie Green’s own words, ‘I get a sandwich and a glass of milk and a book and I read myself to sleep.’”

It could not have been easy being Pumpsie Green in 1959. Lee D. Jenkins, writing in the Chicago Defender after Green’s call-up, lamented the inevitable pressure: “It’s one thing to make a major-league team by sheer talent but to find yourself in a position where you are almost thrust down an unwilling throat makes for a most uncomfortable state. Green was a sensation with the Red Sox during their early spring training but as the season neared the pressure began to tell in his fielding and hitting.”

Boston Celtics basketball star Bill Russell was there to greet Pumpsie when he arrived. They’d known each other since high school. Green also took a call in the Red Sox clubhouse from Jackie Robinson.

After the season Pumpsie was named second baseman on the 1959 Major League Rookie All-Star team, chosen in balloting by 1.7 million Topps gum customers nationally. “Green’s play fell off during the last two or three weeks of the season because he was a tired player,” Jurges said. “I figured he played 260 games last year, counting the winter league, the American Association, and the big leagues. That’s too much ball for a kid.”

After baseball, Green earned a physical-education degree from San Francisco State University and then accepted a position with the Berkeley Unified School District, where he ran the baseball program, coached baseball for 25 years, served as dean of boys for a while, taught mathematics, and did some security work at the school. He finally retired in 1997. Looking back, Pumpsie was frank about Boston and his time in the major leagues. It was a bit of a mixed blessing of sorts, he told Jon Goode: “Sometimes it would get on my nerves. Sometimes I wonder if I would have even made it to the major leagues if it had not been for this Boston thing.

Sometimes I wonder if I would have been better off it was not

for the Boston thing. Things like that you can never answer.”

Green told Danny Peary, “When I was playing, being the first black on the Red

Sox wasn’t nearly as big a source of pride as it would be once I was out of the

game. At the time I never put much stock in it, or thought about it. Later I

understood my place in history. I don’t know if I would have been better in

another organization with more black players. But as it turned out, I became

increasingly proud to have been with the Red Sox as their first black.”

Research more about black baseball players who entered the Major Leagues and share with your babies. Make it a champion day!